Tncs and the Removal of Textiles and Clothing Quotas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Preference Erosion and Multilateral Trade Liberalization*

WPS3730 Preference Erosion and Multilateral Trade Liberalization* Public Disclosure Authorized Joseph François Tinbergen Institute (Rotterdam) and CEPR Bernard Hoekman World Bank, Institut d’Etudes Politiques, Paris and CEPR Miriam Manchin Tinbergen Institute (Rotterdam) Public Disclosure Authorized Abstract: Because of concern that OECD tariff reductions will translate into worsening export performance for the least developed countries, trade preferences have proven a stumbling block to developing country support for multilateral liberalization. We examine the actual scope for preference erosion, including an econometric assessment of the actual utilization, and also the scope for erosion estimated by modeling full elimination of OECD tariffs and hence full MFN liberalization-based preference erosion. Preferences are underutilized due to administrative burden—estimated to be at least 4 percent on average— reducing the magnitude of erosion costs significantly. For those products where preferences are used (are of value), the primary negative impact follows from erosion of EU preferences. This suggests the erosion problem is primarily a bilateral concern. Public Disclosure Authorized Keywords: preference erosion, GSP, WTO, Doha Round, trade and development JEL codes: F13. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 3730, October 2005 The Policy Research Working Paper Series disseminates the findings of work in progress to encourage the exchange of ideas about development issues. An objective of the series is to get the findings out quickly, even if the presentations are less than fully polished. The papers carry the names of the authors and should be cited accordingly. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this paper are entirely those of the authors. They do not necessarily represent the view of the World Bank, its Executive Directors, or the countries they represent. -

The Global Apparel Value Chain, Trade and the Crisis

WPS5281 Policy Research Working Paper 5281 Public Disclosure Authorized The Global Apparel Value Chain, Trade and the Crisis Public Disclosure Authorized Challenges and Opportunities for Developing Countries Gary Gereffi Stacey Frederick Public Disclosure Authorized The World Bank Public Disclosure Authorized Development Research Group Trade and Integration Team April 2010 Policy Research Working Paper 5281 Abstract This paper examines the impact of two crises on the has been the big winner, although Bangladesh, India, global apparel value chain: the World Trade Organization and Vietnam have also continued to expand their roles phase-out of the quota system for textiles and apparel in the industry. On the firm side, the quota phase-out in 2005, which provided access for many poor and and economic recession have accelerated the ongoing small export-oriented economies to the markets of shift to more streamlined global supply chains, in which industrialized countries, and the current economic lead firms desire to work with fewer, larger, and more recession that has lowered demand for apparel exports capable suppliers that are strategically located around the and led to massive unemployment across the industry’s world. The paper concludes with recommendations for supply chain. An overarching trend has been the process how developing countries as well as textile and apparel of global consolidation, whereby leading apparel suppliers suppliers can adjust to the crisis. (countries and firms alike) have strengthened their positions in the industry. On the country side, China This paper—a product of the Trade and Integration Team, Development Research Group (Global Trade and Financial Architecture project supported by DFID)—is part of a larger effort to explore the effects of the world economic crisis on global value chains. -

ICES- El CENTER El CENTER IF Excellence

ICES- El CENTER El CENTER IF EXCEllENCE RESEARCH GRANTS & ' WORKING PAPER SERIES #1 AY2006-0J COMMENTS ARE WELCOME COMPARISON OF PRCAND VIETNAM'S RESPONSES TO THE ELIMINATION OF US TEXTILE AND APPAREL QUOTAS: ECONOMIC AND CULTURAL PERSPECTIVES Joseph Pelzman Department of Economics George Washington University Washington, DC 20052 and Ben-Gurion University of the Negev Beer Sheva, ISRAEL [email protected] and [email protected] 1 COMPARISON OF PRC AND VIETNAM'S RESPONSES TO THE ELIMINATION OF US TEXTILE AND APPAREL QUOTAS: ECONOMIC AND CULTURAL PERSPECTIVES I. INTRODUCfiON International trade in textiles and apparel has, as of January 1, 2005, been set free from the very intricate Multi-Fibertextile and apparel quota Arrangement (l\I1FA). This event has raised many uncertainties about the new international trade climate and has placed enormous pressure on Olina as the expected clear cut beneficiary of this hberalization.' Other countries considered to be major contenders include Vietnam which also has a large population employed in the textile and apparel (T&A) sector. Since the old quota system had provided a certain degree of market certainty to competing T&A producers, will the new free trade environment lead to a shake out where mass producers with large economies of scale dominate the new reality? The removal of T&A quotas will create opportunities for Vietnam and Olina along with other developing countries, but it will also expose them to additional competition from each other. The outcome of this competition will depend on the demand in the US, the ability of the exporting countries to differentiate their exports and on their ability to transfer additional resources to expand domestic output in the direction of the new 'free market signals' and away from rent seeking objectives. -

International Trade and Development

United Nations A/60/225 General Assembly Distr.: General 12 August 2005 Original: English Sixtieth session Item 52 (a) of the provisional agenda* Macroeconomic policy questions International trade and development Report of the Secretary-General Summary The present report covers recent developments in the international trade and the trading system, including the implications for developing countries of multilateral trade negotiations under the World Trade Organization (WTO) Doha work programme since the WTO General Council Decision of 1 August 2004. Consensus has emerged that the Doha negotiations should fulfil their development promise and be concluded expeditiously, by no later than 2006, so as to contribute to the timely implementation of the Millennium Development Goals. The report identifies the interlinkages between different negotiating areas and the Millennium Development Goals. The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) has provided valuable support to developing countries in trade negotiations and development. The São Paulo Consensus of the eleventh session of UNCTAD held in São Paulo, Brazil, from 13 to 18 June 2004, further enhanced the mandate of UNCTAD to support developing countries, especially the least developed countries, in their efforts to ensure gains in development from the international trading system and trade negotiations. * A/60/150. 05-45993 (E) 080905 *0545993* A/60/225 I. Introduction 1. The present report is submitted pursuant to General Assembly resolution 59/221 of 22 December 2004, in which the Assembly requested the Secretary- General, in collaboration with the secretariat of the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), to report to it at its sixtieth session on the implementation of that resolution and on developments in the multilateral trading system. -

OUR SEMI-ANNUAL BLUE PENCIL DRESS GOODS, SILKS And

XJLXXU AVJ JJ-IU JIV AJJA/) UUi>iJ li/U f. — r_ ■ ■ ■■■ I.— ■■ ■■■ ■ II. II II — T Prize for Early Attendants who come in our The doors open promptly at 8:30 a. m. The first hundred women “EAST” entrance will be given a ticket with a number between 1 and 100. The first hundred women who come in our “WEST” entrance will be given a number between Blue Pencil Sales are the Blue 101 and 200. A duplicate set of numbers will be “SHAKEN UP” in a box and a number drawn out. The woman the lucky number gets.her You Know It Too! Bloods of “Saledom” holding A more “Up-Spring-ie” Spring has not been sprung in are the article. come twice a They genuine They only Choice of Skirt in the Store rears, but the Steele-Smith way is to take the bitter with the A store with the kind of don’t need more. any $10 year. right goods sweet and do the best we can always. We anticipated a Of course there are “talk” sales, bnt broad, deep, lasting Fitted, Absolutely Free larger business than weather permitted and bought to back foundations can’t be built on clatter. Properly up” our convictions. The surplus is going in June and the June will be brimful of "Blue Pencil" sales, and we specially urge “Blue Pencil Sales” are here to do it. thrifty women and men to visit the store often and watch our ads closely. BE HERE WHEN THE DOORS OPEN! OUR SEMI-ANNUAL BLUE PENCIL SALES Begin Monday, June 3rd at 8:30 A- M. -

Views of Sourcing Personnel, Which Will

FINISHED GOOD SOURCING DECISIONS IN THE US APPAREL INDUSTRY AFTER IMPLEMENTATION OF THE AGREEMENT ON TEXTILES AND CLOTHING DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Ann Richards Glenn, M.S. ***** The Ohio State University 2006 Dissertation Committee: Professor Leslie Stoel, Advisor Professor Loren Geistfeld Approved by Professor Neal Hooker Professor Catherine Montalto Advisor College of Education and Human Ecology ABSTRACT January 1, 2005 brought the elimination of quantitative restrictions to trade in the apparel industry. Because apparel products are produced in almost every country around the world, the elimination of trade barriers has important implications for apparel sourcing decisions. The research in this dissertation assesses the impact of quota release using two methodologies: interviews of sourcing personnel, which will give a micro-economic view of imports at the company level, and econometrics, which will be used to give a macro-economic view of impacts on the industry. The combination of these two methodologies will give a holistic look at the reduction of trade barriers and their impact on the apparel sourcing decision. The qualitative data consisted of transcripts from interviews of six sourcing personnel. New themes that emerged from the data included vendor relationships, security of country and natural barriers, such as weather phenomena. External environmental barriers, such as economic, political/legal, and socio-cultural barriers, found in previous research were confirmed by the qualitative data. The quantitative data used for this research was collected from various US and international agencies. OLS regression revealed all variables (difference in GDP, geographical distance, duty, real exchange rate, and quota) to be significant. -

Assessing the Impact of the Phasing-Out of the Agreement on Textiles and Clothing on Apparel Exports on the Least Developed and Developing Countries

UC Santa Barbara Other Recent Work Title Assessing the Impact of the Phasing-out of the Agreement on Textiles and Clothing on Apparel Exports on the Least Developed and Developing Countries Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6z33940z Author Appelbaum, Richard P. Publication Date 2004-05-10 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California DRAFT VERSION ONLY – MAY NOT BE CITED OR QUOTED WITHOUT PERMISSION OF THE AUTHOR Assessing the Impact of the Phasing-out of the Agreement on Textiles and Clothing on Apparel Exports on the Least Developed and Developing Countries report by Richard P. Appelbaum Center for Global Studies Institute for Social, Behavioral, and Economic Research University of California at Santa Barbara Santa Barbara, CA 93106 phone: (805) 893-7230 fax: (805) 893-7995 web: www.isber.ucsb.edu email: [email protected] May 10, 2004 Acknowledgements This project was conducted in part for the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, and in part for sweatshop Watch (under a grant from the University of California’s Institute for Labor and Employment). I wish to especially acknowledge the assistance of Joe Conti and Francesca deGiuli, who gathered and analysed much of the research collected for this report. 1 Assessing the Impact of the Phasing-out of the Agreement on Textiles and Clothing on Apparel Exports on the Least Developed and Developing Countries Abstract On January 1, 2005, the Multifiber Arrangement (MFA), which establishes quotas on different categories of apparel and textile imports to the US and the EU, will be fully phased out. -

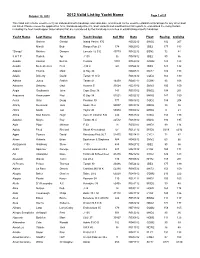

Valid List by Yacht Name Page 1 of 25

October 19, 2012 2012 Valid List by Yacht Name Page 1 of 25 This Valid List is to be used to verify an individual boat's handicap, and valid date, and should not be used to establish a handicaps for any other boat not listed. Please review the appilication form, handicap adjustments, boat variants and modified boat list reports to understand the many factors including the fleet handicapper observations that are considered by the handicap committee in establishing a boat's handicap Yacht Name Last Name First Name Yacht Design Sail Nbr Date Fleet Racing Cruising Gartner Gerald Island Packet 370 R052212 BWS2 192 207 Minelli Bob Ranger Fun 23 174 N062012 JBE2 177 183 "Sloopy" Melcher Dwayne Lacoste 42 S E 40779 R042212 BSN2 72 84 5 H T P Rudich Api J 105 96 R081812 JBE2 90 96 Acadia Keenan Burt H. Custom 1001 R062912 GOM2 123 123 Acadia Biebesheimer Fred J 34 C 69 R052412 JBE2 123 132 Adagio Thuma Mark O Day 30 N040512 MAT2 186 198 Adajio Doherty David Tartan 31 S D R061612 COD2 165 180 Adhara Jones Patrick Tartan 41 14459 R040212 GOM2 93 108 Advance Delaney Ged Avance 33 33524 R021312 SMV2 150 159 Aegis Gaythwaite John Cape Dory 36 141 R051012 BWS2 198 201 Aequoreal Rasmussen Paul O Day 34 51521 R032212 MRN2 147 159 Aerial Gray Doug Pearson 30 777 N061612 COD2 189 204 Affinity Desmond Jack Swan 48-2 50007 R042312 MRN2 33 36 Africa Smith Jud Taylor 45 50974 R030812 MHD2 9 21 Aftica Mac Kenzie Hugh Irwin 31 Citation S D 234 R061512 COD2 183 198 Agadou Mayne Roy Tartan 34 C 22512 R061812 MAN2 180 195 Agila Piper Michael E 33 18 R050912 MHD2 -

Liberalizing Quotas on Textiles and Clothing: Has the ATC Actually Worked?

Liberalizing Quotas on Textiles and Clothing: Has the ATC Actually Worked? June 2004 Joseph F. Francois Dean Spinanger [email protected]) ([email protected]) Tinbergen Institute (Rotterdam) Institute of World Economics, Kiel and CEPR Abstract: We explore the evolution of market access conditions in the textile and clothing sectors (T&C). Working with bilateral trade data on textile and clothing trade, underlying tariffs, and the coverage of quotas under the WTO’s Agreement on Textiles and Clothing (ATC) we first develop a non-linear least squares estimation framework for calculating the tax equivalent of ATC quota restrictions on bilateral trade. We also compare these non-tariff barrier estimates to earlier estimates for the years since the inception of the ATC, to gauge the extent to which the ATC has actually led to quota liberalization. Keywords: Market Access, Textiles and Clothing, WTO accession, quotas, ATC, non-tariff barriers 1. Introduction The Ministerial Declaration at Punta Del Este that launched the Uruguay Round stated that the "Negotiations in the area of textiles and clothing shall aim to formulate modalities that would permit the eventual integration of this sector into GATT on the basis of strengthened GATT rules and disciplines." In plain language, this means that quotas on textiles and clothing were to be eliminated. The negotiations launched at Punta Del Este led to the Agreement on Textiles and Clothing (ATC), an attempt to end almost 40 years of discriminatory protection in violation of the basic precepts of the GATT system. The textile and clothing (T&C) sectors had previously been treated as a special case within the world trading system, with their own regulatory framework. -

Textiles and Clothing: Reflections on the Sector's Integration Into the Post

¾ Textiles and clothing: Reflections on the sector’s integration into the post-quota environment by Eckart Naumann tralac Working Paper No 1/2005 March 2005 The views presented in this paper are those of the author alone and do not necessarily reflect those of tralac (Trade Law Centre for Southern Africa). Any errors are the author’s own. tralac (Trade Law Centre for Southern Africa) p.o.box 224, stellenbosch, 7599 south africa c.l.marais building, crozier street, stellenbosch (t) +27 21 883-2208 (f) +27 21 883-8292 (e) [email protected] © Copyright Trade Law Centre for Southern Africa 2005 The views presented in this paper are those of the author alone and do not necessarily reflect those of tralac (Trade Law Centre for Southern Africa). Any errors are the author’s own. tralac (Trade Law Centre for Southern Africa) p.o.box 224, stellenbosch, 7599 south africa c.l.marais building, crozier street, stellenbosch (t) +27 21 883-2208 (f) +27 21 883-8292 (e) [email protected] © Copyright Trade Law Centre for Southern Africa 2005 Abstract This paper tracks developments of the global textile and clothing quota regime from its early stages in the 1960s to the final integration of the sector into world trade on 1 January 2005. This is followed by a brief analysis of trends in the textile and clothing trade, focusing on key markets in general, and that of the United States in particular, while highlighting the importance of the sector for developing countries. With the Agreement on Textiles and Clothing (ATC) likely to cause substantial shifts in both trade and production within the sector, with a resultant range of economic impacts, the paper concludes by outlining key outcomes that can be expected in the post-quota environment. -

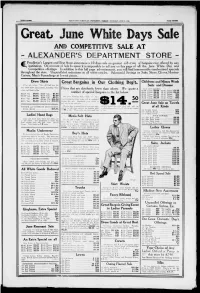

ALEXANDER's DEPARTMENT STORE - TT Pendleton's Largest and Best Store Announces a 10 Days Sale on Greatest Collection of Bargains Ever Offered by Any Ml Institution

EIGIIT PAGES. DAILY EAKT oaKGONIAN, PENDLETON, OREGON. THURSDAY, JUNE , 110. PAGK TURKIC AND COMPETITIVE SALE AT - ALEXANDER'S DEPARTMENT STORE - TT Pendleton's Largest and Best Store announces a 10 days sale on greatest collection of bargains ever offered by any Ml institution. On account of lack fo space it is impossible to tell you on this page of all the June White Day and Competitive offerings. In addition to this full page advertisement, you will find innumerable unadvertised specials throughout the store. Unparalleled reductions on all white articles. Substantial Savings on Suits, Shoes, Gloves, Hosiery Corsets, Men's Furnishings at lowest prices. Dress Skirts Great Bargains in Our Clothing Dep't. Childrens and Misses Wash All at sale prices. You will find here the Suits and Dresses very latent styles and patterns, including white Prices that are absolutely lower than others. We quote a Both white and colors. servos and black voiles. $5.00 Values $3.00 $2.00 Values $1.25 number of special bargains in the list below. $4.50 Values $2.25 $1.75 Values $1.00 $12.50 Val $8.75 $6.00 Val $4.75 $3.50 Values $1.75 $1.50 Values 85?-- $5.50 Val. $10.00 Vaul $6.75 $4.00 Our great Clothing Sale, which we have $3.00 Values $1.50 $1.25 Values.-- .. 75 $5.00 Val.. $3.75 $2.50 Values $1.50 $1.00 Values...... 60 $7.75 v. .$U.OO $15 0Q Va $1150 been running for three weeks will be continued $0.75 Val $5.00 $10.50 Val. -

Perth Amboy, NJ

Panama Hats at Kid Gloves For Special For Dollar Day "Always War With High Prices" Not Banded or Shaped Dollar Day Real PannmaHats for M e or W m e . Some are The finest of French m- 1 slightly stained Kid Gloves in black, white from water and colors, some are just while on board Foster's All ship, only 50 slightly soiled at wrist. on sale at each Bargains to Worth J. H. Foster, 97-99 Smith Street, Perth Amboy, N. J. sizes, 5 7%. $2.50 $1.00 "Patronize Us Only If We Undersell" Special $1.00 A Grand Bargain Drive—Dollar Propositions That Simply Win From Start To Finish Parasols A Genuine Bargain Dollar Day Shirt Waists Very Special For Dollar Day Envelope Dollar Day Corsets Chemise 23 in the lot but Only For the slender figure, At least 10 styles of good values, plain and fancy borders, all silk a pink brocade corset dainty chemise made of or mixed. Special Sat- with elastic top, lightly fine soft mull, lace and urday boned. Other models for each $1.00 ribbon trimmed. White, stouter figures, have flesh and lavender. All Dollar Day Turkish Towels longer skirts and more sizes to 44 Large white turkish towels. Size 23x45. They are like each every thing else, every time we buy we have to bust support. Value $1.50 $1.00 pay big advance. These were bought AA (JM to $2.00. Sat. - f\C\ long ago. Sale price—3 for ./ Dollar Sheets each . Day ■μ* Fifteen styles displayed on large take your Seamed Red table, Sheets, size 72x90.