Traditional Public Administration Versus the New Public Management: Accountability Versus Efficiency

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Managing Meritocracy in Clientelistic Democracies∗

Managing Meritocracy in Clientelistic Democracies∗ Sarah Brierleyy Washington University in St Louis May 8, 2018 Abstract Competitive recruitment for certain public-sector positions can co-exist with partisan hiring for others. Menial positions are valuable for sustaining party machines. Manipulating profes- sional positions, on the other hand, can undermine the functioning of the state. Accordingly, politicians will interfere in hiring partisans to menial position but select professional bureau- crats on meritocratic criteria. I test my argument using novel bureaucrat-level data from Ghana (N=18,778) and leverage an exogenous change in the governing party to investigate hiring pat- terns. The results suggest that partisan bias is confined to menial jobs. The findings shed light on the mixed findings regarding the effect of electoral competition on patronage; competition may dissuade politicians from interfering in hiring to top-rank positions while encouraging them to recruit partisans to lower-ranked positions [123 words]. ∗I thank Brian Crisp, Stefano Fiorin, Barbara Geddes, Mai Hassan, George Ofosu, Dan Posner, Margit Tavits, Mike Thies and Daniel Triesman, as well as participants at the African Studies Association Annual Conference (2017) for their comments. I also thank Gangyi Sun for excellent research assistance. yAssistant Professor, Department of Political Science, Washington University in St. Louis. Email: [email protected]. 1 Whether civil servants are hired by merit or on partisan criteria has broad implications for state capacity and the overall health of democracy (O’Dwyer, 2006; Grzymala-Busse, 2007; Geddes, 1994). When politicians exchange jobs with partisans, then these jobs may not be essential to the running of the state. -

A Historical Perspective in the Study and Practice of Public Administration

Is American Public Administration Detached from Historical Context? On the Nature of Time and the Need to Understand it in Government and its Study Jos C.N. Raadschelders University of Oklahoma Paper for the Sixth NIG Annual work Conference 12-13 November, 2009 University of Leiden 1 Is American Public Administration Detached from Historical Context? On the Nature of Time and the Need to Understand it in Government and its Study Abstract The study of public administration pays little attention to history. Most publications are focused on current problems (the present) and desired solutions (the future) and are concerned mainly with organizational structure (a substantive issue) and output targets (an aggregative issue that involves measures of both individual performance and organizational productivity/services). There is much less consideration of how public administration (i.e., organization, policy, the study, etc.) unfolds over time. History, and so administrative history, is regarded as a ‘past’ that can be recorded for its own sake but has little relevance to contemporary challenges. This view of history is the product of a diminished and anemic sense of time, resulting from organizing the past as a series of events that inexorably lead up to the present in a linear fashion. In order to improve the understanding of government’s role and position in society, public administration scholarship needs to reacquaint itself with the nature of time. “Wir wollen durch Erfahrung nicht sowohl klug (für ein andermal) als weise (für immer) werden.” (Jacob Burckhardt)1 “…excluding useful [memories and histories] because they carry an undesirable residue from the past renders public administration dialogue weaker and less effective in dealing with current problems for the future.” (paraphrased after Box, 2008, p.104) 1. -

Determinants and Consequences of Bureaucrat Effectiveness: Evidence

Determinants and Consequences of Bureaucrat Effectiveness: Evidence from the Indian Administrative Service∗ Marianne Bertrand, Robin Burgess, Arunish Chawla and Guo Xu† October 21, 2015 Abstract Do bureaucrats matter? This paper studies high ranking bureaucrats in India to examine what determines their effectiveness and whether effective- ness affects state-level outcomes. Combining rich administrative data from the Indian Administrative Service (IAS) with a unique stakeholder survey on the effectiveness of IAS officers, we (i) document correlates of individual bureaucrat effectiveness, (ii) identify the extent to which rigid seniority-based promotion and exit rules affect effectiveness, and (iii) quantify the impact of this rigidity on state-level performance. Our empirical strategy exploits variation in cohort sizes and age at entry induced by the rule-based assignment of IAS officers across states as a source of differential promotion incentives. JEL classifica- tion: H11, D73, J38, M1, O20 ∗This project represents a colloboration between the Lal Bahadur Shastri National Academy of Administration (LBSNAA), the University of Chicago and London School of Economics. We are grateful to Padamvir Singh, the former Director of LBSNAA for his help with getting this project started. The paper has benefited from seminar/conference presentations at Berkeley, Bocconi, CEPR Public Economics Conference, IGC Political Economy Conference, LBSNAA, LSE, NBER India Conference, Stanford and Stockholm University. †Marianne Bertrand [University of Chicago Booth School of Business: Mari- [email protected]]; Robin Burgess [London School of Economics (LSE) and the International Growth Centre (IGC): [email protected]]; Arunish Chawla [Indian Administrative Service (IAS)]; Guo Xu [London School of Economics (LSE): [email protected]] 1 1 Introduction Bureaucrats are a core element of state capacity. -

An Introduction to Public Adminstration

Module I Unit 1 1 AN INTRODUCTION TO PUBLIC ADMINSTRATION Meaning & Scope Unit Structure - 0.1 Introduction 0.2 Definition of Public Adminstration 0.3 Scope of Public Adminstration 0.4 Role and Importance of Public Adminstration. 0.5 Unit End Questions OBJECTIVE Public Adminstration is an activity as old as human civilization. In modern age it became the dominant factor of life. To Study about meaning, scope and importance of Public Adminstration is the main objective of this unit. 1.1 INTRODUCTION Public Adminstration as independent Subject of a social science has recent origin. Traditionly Public Adminstration was considered as a part of political science. But in Modern age the nature of state-under went change and it became from police stale to social service state. As a consequence, the Public Adminstration, irrespective of the nature of the political system, has become the dominant factor of life. The modern political system is essentially ‘bureaucratic’ and characterised by the rule of officials. Hence modern democracy has been described as ‘executive democracy’ or ‘bupeaucratic democracy’. The adminstrative branch, described as civil service or bureaucracy is the most significant component of governmental machinery of the state. 1.2 Meaning of Public Adminstration :- Administer is a English word, which is originated from the Latin word ‘ad’ and ‘ministrare’. It means to serve or to manage. Adminstration means mangement of affairs, public or private. Various definitions of Public Adminstration are as follows- 1.2.1 : Prof. Woodrow Wilson, the pioneer of the social science of Public Adminstration says in his book ‘The study of Public 2 Adminstration’, published in 1887 “Public Adminstration is a detailed and systematic application of law.” 1.2.2 : According to L. -

Management and Administration

2 Management and Administration distribute or The first dichotomy we will discuss in this book is between public administration and public management. As was pointed out in Chapter 1, we see public management as embedded in public administration. Therefore, the dichotomy we will address in this chapter refers to the tensions between those two different perspectives – management versus administrationpost, – on fundamental issues related to the bureaucracy. These will include its relationship to elected officials and its clients, and the values and norms that are prioritized in the two perspectives. These differences are most distinct and pertinent when we confront conventional public administration with New Public Management (NPM) which is the cur- rently dominant version of public management thinking and a neo-Weberian philosophy of public service. Thus, our discussion about public management is mainly related to NPM, although we will also trace the history of the public management copy,school of thought. This chapter will look more closely at the shift from public administration to public management in the scholarly literature and also in the debate among politicians and civil servants. We first discuss the different meanings and conse- notquences of the shift from public administration to public management. After that, and as a way of further clarifying what the concepts of public administration and public management stand for, we will stylize the two different approaches to the public sector and its organizations. We then conclude the chapter by discussing whether there is today some degree of convergence between the two approaches Do and, if so, what that position means and the degree to which neo-Weberianism deviates from those two approaches. -

THE LAWYER's ROLE in PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION FRITZ MORSTEIN Marxt

THE LAWYER'S ROLE IN PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION FRITZ MORSTEIN MARXt I THE role played by the lawyer in public administration is not ade- quately described in a simple statement. His special skill is utilized in a great variety of ways. Moreover, lawyers occupy quite different posi- tions on various levels of the administrative hierarchy. And their actual influence goes in many instances beyond the range of their specific duties. Neither statutory prohibitions nor stipulations of political etiquette bar the lawyer from the highest posts of administrative leadership. It may even be said that legislative assemblies-with their heavy representation of legal talent-tend to show a certain fondness for government executives experienced in the practice of law.' More than a few lawyers have acquitted themselves creditably at the helm of gov- ernment agencies. This, however, does not suggest the possibility of a correlation between success or acclaim in the legal profession and those qualifications which should be expected of government executives. 2 On the contrary, prevailing opinion is accurately summarized in the ob- servation that "the lawyer is a good administrator by coincidence only; he is not specially trained for administration, and, indeed, the narrow and specialized legal education he has received may be considered to be particularly unsuited for the types of problems to be faced." I What is more relevant for our purposes, as administrator of an operating agency the lawyer is called upon to demonstrate his talent for executive direction and management rather than his legal knowledge and experi- ence. Much the same is true of those lawyers whose elevated positions t Associate Professor of Political Science, Queens College (on leave); Staff Assistant, Office of the Director, Bureau of the Budget, Executive Office of the President. -

Engineers in India: Industrialisation, Indianisation and the State, 1900-47

Engineers in India: Industrialisation, Indianisation and the State, 1900-47 A P A R A J I T H R AMNATH July 2012 A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Imperial College London Centre for the History of Science, Technology and Medicine DECLARATION This thesis represents my own work. Where the work of others is mentioned, it is duly referenced and acknowledged as such. APARAJITH RAMNATH Chennai, India 30 July 2012 2 ABSTRACT This thesis offers a collective portrait of an important group of scientific and technical practitioners in India from 1900 to 1947: professional engineers. It focuses on engineers working in three key sectors: public works, railways and private industry. Based on a range of little-used sources, it charts the evolution of the profession in terms of the composition, training, employment patterns and work culture of its members. The thesis argues that changes in the profession were both caused by and contributed to two important, contested transformations in interwar Indian society: the growth of large-scale private industry (industrialisation), and the increasing proportion of ‘native’ Indians in government services and private firms (Indianisation). Engineers in the public works and railways played a crucial role as officers of the colonial state, as revealed by debates on Indianisation in these sectors. Engineers also enabled the emergence of large industrial enterprises, which in turn impacted the profession. Previously dominated by expatriate government engineers, the profession expanded, was considerably Indianised, and diversified to include industrial experts. Whereas the profession was initially oriented towards the imperial metropolis, a nascent Indian identity emerged in the interwar period. -

Closing State Infrastructure Gaps 4-1

Introduction Rebuilding America’s crumbling infrastructure Back in the 1960s, California was known for Business leaders echo the public’s concern about 4 more than just Hollywood, The Beach Boys and the widening gap between infrastructure needs beautiful scenery. The state was also famous and current spending. Among surveyed senior for its unparalleled infrastructure. California had business executives, 77 percent believe that the one of the world’s most extensive transportation current level of public infrastructure is inadequate to infrastructure programs in the late 1950s and support their companies’ long-term growth. These early 1960s, which paved the way for much of executives believe that over the next few years, the state’s subsequent economic prosperity. infrastructure will become a more important factor in determining where they locate their operations.65 Those times seem like ancient history in California and throughout America. Today, crowded schools, While there is widespread agreement on the traffic-choked roads, deteriorating bridges, and need to address the growing public infrastructure aged and overused water and sewer treatment deficit, both to create jobs in the short term and facilities undercut the economy’s efficiency and as a prerequisite for enhancing economic develop- erode the quality of American life (see figure 4-1). ment and competitiveness in the longer term, The American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) states find themselves in a difficult and precarious estimates that the United States currently only position with respect to how to pay for it. invests about half of what is needed to bring the nation’s infrastructure up to a good condition. -

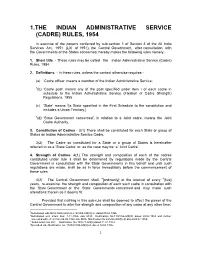

1.The Indian Administrative Service (Cadre) Rules, 1954

1.THE INDIAN ADMINISTRATIVE SERVICE (CADRE) RULES, 1954 In exercise of the powers conferred by sub-section 1 of Section 3 of the All India Services Act, 1951 (LXI of 1951), the Central Government, after consultation with the Governments of the States concerned, hereby makes the following rules namely:- 1. Short title: - These rules may be called the Indian Administrative Service (Cadre) Rules, 1954. 2. Definitions: - In these rules, unless the context otherwise requires - (a) ‘Cadre officer’ means a member of the Indian Administrative Service; 1(b) ‘Cadre post’ means any of the post specified under item I of each cadre in schedule to the Indian Administrative Service (Fixation of Cadre Strength) Regulations, 1955. (c) ‘State’ means 2[a State specified in the First Schedule to the constitution and includes a Union Territory.] 3(d) ‘State Government concerned’, in relation to a Joint cadre, means the Joint Cadre Authority. 3. Constitution of Cadres - 3(1) There shall be constituted for each State or group of States an Indian Administrative Service Cadre. 3(2) The Cadre so constituted for a State or a group of States is hereinafter referred to as a ‘State Cadre’ or, as the case may be, a ‘Joint Cadre’. 4. Strength of Cadres- 4(1) The strength and composition of each of the cadres constituted under rule 3 shall be determined by regulations made by the Central Government in consultation with the State Governments in this behalf and until such regulations are made, shall be as in force immediately before the commencement of these rules. 4(2) The Central Government shall, 4[ordinarily] at the interval of every 4[five] years, re-examine the strength and composition of each such cadre in consultation with the State Government or the State Governments concerned and may make such alterations therein as it deems fit: Provided that nothing in this sub-rule shall be deemed to affect the power of the Central Government to alter the strength and composition of any cadre at any other time: 1Substituted vide MHA Notification No.14/3/65-AIS(III)-A, dated 05.04.1966. -

Bureaucratic Indecision and Risk Aversion in India

Working Paper Bureaucratic Indecision and Risk Aversion in India Sneha P., Neha Sinha, Ashwin Varghese, Avanti Durani and Ayush Patel. About Us IDFC Institute has been set up as a research-focused think/do tank to investigate the political, economic and spatial dimensions of India’s ongoing transition from a low-income, state-led country to a prosperous market-based economy. We provide in-depth, actionable research and recommendations that are grounded in a contextual understanding of the political economy of execution. Our work rests on two pillars — ‘Transitions’ and ‘State and the Citizen’. ‘Transitions’ addresses the three transitions that are vital to any developing country’s economic advancement: rural to urban, low to high productivity, and the move from the informal to formal sector. The second pillar seeks to redefine the relationship between state and citizen to one of equals, but also one that keeps the state accountable and in check. This includes improving the functioning and responsiveness of important formal institutions, including the police, the judicial system, property rights etc. Well-designed, well-governed institutions deliver public goods more effectively. All our research, papers, databases, and recommendations are in the public domain and freely accessible through www.idfcinstitute.org. Disclaimer and Terms of Use The analysis in this paper is based on research by IDFC Institute (a division of IDFC Foundation). The views expressed in this paper are not that of IDFC Limited or any of its affiliates. The copyright of this paper is the sole and exclusive property of IDFC Institute. You may use the contents only for non-commercial and personal use, provided IDFC Institute retains all copyright and other proprietary rights contained therein and due acknowledgement is given to IDFC Institute for usage of any content. -

Dance & Visual Impairment

Dance & Visual Impairment For an Accessibility of Choreographic Practices ANDRÉ FERTIER Cemaforre-European Centre for Cultural Accessibility CENTRE3 NATIONAL DE LA DANSE Dance & Visual Impairment For an Accessibility of Choreographic Practices This digital edition of Dance & Visual Impairment: For an Accessibility of Choreographic Practices was produced in July 2017 by Centre national de la danse and Cemaforre-European Centre for Cultural Accessibility, adapted from Danse & handicap visuel : pour une accessibilité des pratiques chorégraphiques (ISBN : 978-2-914124-50-8 – ISSN: 1621-4153). This book is also available in accessible EPUB3 and DAISY format. CN D is a public institution with an industrial and commercial function funded by the Ministry of Culture. This digital edition was produced as part of the project The Humane Body. The Humane Body is co-funded by the Creative Europe Programme of the European Union. This project was made possible thanks to the collaboration between CN D Centre national de la danse in Pantin and Wiener Tanzwochen/ImPulsTanz in Vienna, Kaaitheater in Brussels, The Place in London. Editorial Board: Patricia Darif (La Possible Échappée), Delphine Demont (Acajou), André Fertier (Cemaforre), Myrha Govindjee (Cemaforre), Brigitte Hyon (CND), Christine Lapoujade (Cemaforre), Florence Lebailly (CND), Amélie Leroy (Cemaforre), Kathy Mépuis (La Possible Échappée), Jonathan Rohman (Cemaforre). Centre national de la danse / www.cnd.fr Chairman of the board of directors: Marie-Vorgan Le Barzic Director and senior editor: -

COVID-19 and Public Administration: Global Economic Management

COVID-19 and Public Administration: Global Economic Management Mahboob Ullah, Enayatullah Habibi, Hamdullah Nezami To Link this Article: http://dx.doi.org/10.6007/IJAREMS/v10-i1/9183 DOI:10.6007/IJAREMS/v10-i1/9183 Received: 02 January 2021, Revised: 28 January 2021, Accepted: 23 February 2021 Published Online: 24 March 2021 In-Text Citation: (Ullah et al., 2021) To Cite this Article: Ullah, M., Habibi, E., & Nezami, H. (2021). COVID-19 and Public Administration: Global Economic Management. International Journal of Academic Research in Economics and Managment and Sciences, 10(1), 34-45. Copyright: © 2021 The Author(s) Published by Human Resource Management Academic Research Society (www.hrmars.com) This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license. Anyone may reproduce, distribute, translate and create derivative works of this article (for both commercial and non-commercial purposes), subject to full attribution to the original publication and authors. The full terms of this license may be seen at: http://creativecommons.org/licences/by/4.0/legalcode Vol. 10, No. 1, 2021, Pg. 34 - 45 http://hrmars.com/index.php/pages/detail/IJAREMS JOURNAL HOMEPAGE Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://hrmars.com/index.php/pages/detail/publication-ethics 34 International Journal of Academic Research economics and management sciences Vol. 10, No. 1, 2021, E-ISSN: 2226-3624 © 2021 HRMARS COVID-19 and Public Administration: Global Economic Management Mahboob Ullah Associate Professor, Department of Management Sciences, Khurasan University, Nangarhar, Afghanistan Enayatullah Habibi Assistant Professor, Head of Business Administration Department, Economics Faculty Nangarhar University, Afghanistan Hamdullah Nezami Associate professor, Head of National Economics Department, Economics Faculty Nangarhar University, Afghanistan Email: [email protected] Abstract The entire world community, starting in mid-December 2019, has come under the enormous influence of the World Coronavirus Epidemic, called COVID-19.