A Foreign Policy of Abolitionism: Great Britain’S Use Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contents Graphic—Description of a Slave Ship

1 Contents Graphic—Description of a Slave Ship .......................................................................................................... 2 One of the Oldest Institutions and a Permanent Stain on Human History .............................................................. 3 Hostages to America .............................................................................................................................. 4 Human Bondage in Colonial America .......................................................................................................... 5 American Revolution and Pre-Civil War Period Slavery ................................................................................... 6 Cultural Structure of Institutionalized Slavery................................................................................................ 8 Economics of Slavery and Distribution of the Enslaved in America ..................................................................... 10 “Slavery is the Great Test [] of Our Age and Nation” ....................................................................................... 11 Resistors ............................................................................................................................................ 12 Abolitionism ....................................................................................................................................... 14 Defenders of an Inhumane Institution ........................................................................................................ -

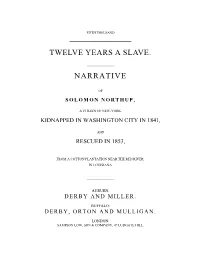

Twelve Years a Slave. Narrative

FIFTH THOUSAND TWELVE YEARS A SLAVE. NARRATIVE OF SOLOMON NORTHUP, A CITIZEN OF NEW-YORK, KIDNAPPED IN WASHINGTON CITY IN 1841, AND RESCUED IN 1853, FROM A COTTON PLANTATION NEAR THE RED RIVER, IN LOUISIANA. AUBURN: DERBY AND MILLER. BUFFALO: DERBY, ORTON AND MULLIGAN. LONDON: SAMPSON LOW, SON & COMPANY, 47 LUDGATE HILL. 1853. Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year one thousand eight hundred and fifty-three, by D E R B Y A N D M ILLER , In the Clerk's Office of the District Court of the Northern District of New-York. ENTERED IN LONDON AT STATIONERS' HALL. TO HARRIET BEECHER STOWE: WHOSE NAME, THROUGHOUT THE WORLD, IS IDENTIFIED WITH THE GREAT REFORM: THIS NARRATIVE, AFFORDING ANOTHER Key to Uncle Tom's Cabin, IS RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED "Such dupes are men to custom, and so prone To reverence what is ancient, and can plead A course of long observance for its use, That even servitude, the worst of ills, Because delivered down from sire to son, Is kept and guarded as a sacred thing. But is it fit, or can it bear the shock Of rational discussion, that a man Compounded and made up, like other men, Of elements tumultuous, in whom lust And folly in as ample measure meet, As in the bosom of the slave he rules, Should be a despot absolute, and boast Himself the only freeman of his land?" Cowper. [Pg vii] CONTENTS. PAGE. EDITOR'S PREFACE, 15 CHAPTER I. Introductory—Ancestry—The Northup Family—Birth and Parentage—Mintus Northup—Marriage with Anne Hampton—Good Resolutions—Champlain Canal—Rafting Excursion to Canada— Farming—The Violin—Cooking—Removal to Saratoga—Parker and Perry—Slaves and Slavery— The Children—The Beginning of Sorrow, 17 CHAPTER II. -

Download the List of History Films and Videos (PDF)

Video List in Alphabetical Order Department of History # Title of Video Description Producer/Dir Year 532 1984 Who controls the past controls the future Istanb ul Int. 1984 Film 540 12 Years a Slave In 1841, Northup an accomplished, free citizen of New Dolby 2013 York, is kidnapped and sold into slavery. Stripped of his identity and deprived of dignity, Northup is ultimately purchased by ruthless plantation owner Edwin Epps and must find the strength to survive. Approx. 134 mins., color. 460 4 Months, 3 Weeks and Two college roommates have 24 hours to make the IFC Films 2 Days 235 500 Nations Story of America’s original inhabitants; filmed at actual TIG 2004 locations from jungles of Central American to the Productions Canadian Artic. Color; 372 mins. 166 Abraham Lincoln (2 This intimate portrait of Lincoln, using authentic stills of Simitar 1994 tapes) the time, will help in understanding the complexities of our Entertainment 16th President of the United States. (94 min.) 402 Abe Lincoln in Illinois “Handsome, dignified, human and moving. WB 2009 (DVD) 430 Afghan Star This timely and moving film follows the dramatic stories Zeitgest video 2009 of your young finalists—two men and two very brave women—as they hazard everything to become the nation’s favorite performer. By observing the Afghani people’s relationship to their pop culture. Afghan Star is the perfect window into a country’s tenuous, ongoing struggle for modernity. What Americans consider frivolous entertainment is downright revolutionary in this embattled part of the world. Approx. 88 min. Color with English subtitles 369 Africa 4 DVDs This epic series presents Africa through the eyes of its National 2001 Episode 1 Episode people, conveying the diversity and beauty of the land and Geographic 5 the compelling personal stories of the people who shape Episode 2 Episode its future. -

1 1. Suppression of the Atlantic Slave Trade

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Leeds Beckett Repository 1. Suppression of the Atlantic slave trade: Abolition from ship to shore Robert Burroughs This study provides fresh perspectives on criticalaspects of the British Royal Navy’s suppression of the Atlantic slave trade. It is divided into three sections. The first, Policies, presents a new interpretation of the political framework underwhich slave-trade suppression was executed. Section II, Practices, examines details of the work of the navy’s West African Squadronwhich have been passed over in earlier narrativeaccounts. Section III, Representations, provides the first sustained discussion of the squadron’s wider, cultural significance, and its role in the shaping of geographical knowledge of West Africa.One of our objectives in looking across these three areas—a view from shore to ship and back again--is to understand better how they overlap. Our authors study the interconnections between political and legal decision-making, practical implementation, and cultural production and reception in an anti-slavery pursuit undertaken far from the metropolitan centres in which it was first conceived.Such an approachpromises new insights into what the anti-slave-trade patrols meant to Britain and what the campaign of ‘liberation’ meant for those enslaved Africans andnavalpersonnel, including black sailors, whose lives were most closely entangled in it. The following chapters reassess the policies, practices, and representations of slave- trade suppression by building upon developments in research in political, legal and humanitarian history, naval, imperial and maritime history, medical history, race relations and migration, abolitionist literature and art, nineteenth-century geography, nautical literature and art, and representations of Africa. -

Slave Trade a Select Bibliography

SLAVE TRADE A SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY In Commemoration of the 200thAnniversary of the Abolition of the Slave Trade Compiled by Nicole Bryan Genevieve Jones Jessica Lewis Princena Miller Bernadette Worrell National Library of Jamaica 2007 ii Copyright © 2007 by National Library of Jamaica 12 East Street Kingston All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced without written permission from the National Library of Jamaica. Images on Cover (left to right) 1. Slave Auction (J. Blake, Photographer) 2. Group of Negroes as Imported to be Sold as Slaves 3. Sold Into Slavery 4. Negroes Captives Being Forced on Slave Boat Slave trade : a selected bibliography / compiled by the National Library of Jamaica. p. ; cm. In commemoration of the 200th anniversary of the abolition of the slave trade ISBN 978-976-8020-04-8 (pbk) 1. Slave trade - Bibliography. 2. Slavery - Bibliography I. National Library of Jamaica 016.306362 dc 22 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ........................................................................................2 Chronology of the Slave Trade ...........................................................4 Reference Notes .................................................................................8 Books and Pamphlets .........................................................................9 Periodical Articles..............................................................................44 Newspaper References.....................................................................47 Manuscripts.......................................................................................53 -

Uneasy Intimacies: Race, Family, and Property in Santiago De Cuba, 1803-1868 by Adriana Chira

Uneasy Intimacies: Race, Family, and Property in Santiago de Cuba, 1803-1868 by Adriana Chira A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Anthropology and History) in the University of Michigan 2016 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Jesse E. Hoffnung-Garskof, Co-Chair Professor Rebecca J. Scott, Co-Chair Associate Professor Paulina L. Alberto Professor Emerita Gillian Feeley-Harnik Professor Jean M. Hébrard, École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales Professor Martha Jones To Paul ii Acknowledgments One of the great joys and privileges of being a historian is that researching and writing take us through many worlds, past and present, to which we become bound—ethically, intellectually, emotionally. Unfortunately, the acknowledgments section can be just a modest snippet of yearlong experiences and life-long commitments. Archivists and historians in Cuba and Spain offered extremely generous support at a time of severe economic challenges. In Havana, at the National Archive, I was privileged to get to meet and learn from Julio Vargas, Niurbis Ferrer, Jorge Macle, Silvio Facenda, Lindia Vera, and Berta Yaque. In Santiago, my research would not have been possible without the kindness, work, and enthusiasm of Maty Almaguer, Ana Maria Limonta, Yanet Pera Numa, María Antonia Reinoso, and Alfredo Sánchez. The directors of the two Cuban archives, Martha Ferriol, Milagros Villalón, and Zelma Corona, always welcomed me warmly and allowed me to begin my research promptly. My work on Cuba could have never started without my doctoral committee’s support. Rebecca Scott’s tireless commitment to graduate education nourished me every step of the way even when my self-doubts felt crippling. -

Can Words Lead to War?

Middle School Uncle Tom’s Cabin Inquiry Can Words Lead to War? Full-page illustration from first edition Uncle Tom’s Cabin by Hammatt Billings. Available in Uncle Tom’s Cabin & American Culture. Supporting Questions 1. How did Harriet Beecher Stowe describe slavery in Uncle Tom’s Cabin? 2. What led Harriet Beecher Stowe to write Uncle Tom’s Cabin? 3. How did northerners and southerners react to Uncle Tom’s Cabin? 4. How did Uncle Tom’s Cabin affect abolitionism? THIS WORK IS LICENSED UNDER A CREATIVE COMMONS ATTRIBUTION- NONCOMMERCIAL- SHAREALIKE 4.0 INTERNATIONAL LICENSE. 1 Middle School Uncle Tom’s Cabin Inquiry Can Words Lead to War? Framework for Summary Objective 12: Students will understand the growth of the abolitionist movement in the Teaching American 1830s and the Southern view of the movement as a physical, economic and political threat. Slavery Consider the power of words and examine a video of students using words to try to bring about Staging the Question positive change. Supporting Question 1 Supporting Question 2 Supporting Question 3 Supporting Question 4 How did Harriet Beecher What led Harriet Beecher How did people in the How did Uncle Tom’s Stowe describe slavery in Stowe to write Uncle North and South react to Cabin affect abolitionism? Uncle Tom’s Cabin? Tom’s Cabin? Uncle Tom’s Cabin? Formative Formative Formative Formative Performance Task Performance Task Performance Task Performance Task Complete a source analysis List four quotes from the Make a T-chart comparing Participate in a structured chart to write a summary sources that point to the viewpoints expressed discussion regarding the of Uncle Tom’s Cabin that Stowe’s motivation and in northern and southern impact Uncle Tom’s Cabin includes main ideas and write a paragraph newspaper reviews of had on abolitionism. -

Abolitionist Movement

Abolitionist Movement The goal of the abolitionist movement was the immediate emancipation of all slaves and the end of racial discrimination and segregation. Advocating for immediate emancipation distinguished abolitionists from more moderate anti-slavery advocates who argued for gradual emancipation, and from free-soil activists who sought to restrict slavery to existing areas and prevent its spread further west. Radical abolitionism was partly fueled by the religious fervor of the Second Great Awakening, which prompted many people to advocate for emancipation on religious grounds. Abolitionist ideas became increasingly prominent in Northern churches and politics beginning in the 1830s, which contributed to the regional animosity between North and South leading up to the Civil War. The Underground Railroad c.1780 - 1862 The Underground Railroad, a vast network of people who helped fugitive slaves escape to the North and to Canada, was not run by any single organization or person. Rather, it consisted of many individuals -- many whites but predominantly black -- who knew only of the local efforts to aid fugitives and not of the overall operation. Still, it effectively moved hundreds of slaves northward each year -- according to one estimate, the South lost 100,000 slaves between 1810 and 1850. Still, only a small percentage of escaping slaves received assistance from the Underground Railroad. An organized system to assist runaway slaves seems to have begun towards the end of the 18th century. In 1786 George Washington complained about how one of his runaway slaves was helped by a "society of Quakers, formed for such purposes." The system grew, and around 1831 it was dubbed "The Underground Railroad," after the then emerging steam railroads. -

Racism in Cuba Ronald Jones

University of Chicago Law School Chicago Unbound International Immersion Program Papers Student Papers 2015 A Revolution Deferred: Racism in Cuba Ronald Jones Follow this and additional works at: http://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/ international_immersion_program_papers Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Ronald Jones, "A Revolution Deferred: Racism in Cuba," Law School International Immersion Program Papers, No. 9 (2015). This Working Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Papers at Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Immersion Program Papers by an authorized administrator of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. qwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqw ertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwert yuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyui opasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopaA Revolution Deferred sdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfRacism in Cuba 4/25/2015 ghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghj Ron Jones klzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklz xcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcv bnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbn mqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmq wertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwe rtyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwerty uiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuio pasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopas dfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfg hjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjk Contents Introduction .............................................................................................................................................. 2 Slavery in Cuba ....................................................................................................................................... -

Freedom's Mirror Cuba and Haiti in the Age of Revolution by Ada Ferrer

Freedom’s Mirror During the Haitian Revolution of 1791–1804,arguablythemostradi- cal revolution of the modern world, slaves and former slaves succeeded in ending slavery and establishing an independent state. Yet on the Spanish island of Cuba, barely fifty miles away, the events in Haiti helped usher in the antithesis of revolutionary emancipation. When Cuban planters and authorities saw the devastation of the neighboring colony, they rushed to fill the void left in the world market for sugar, to buttress the institutions of slavery and colonial rule, and to prevent “another Haiti” from happening in their territory. Freedom’s Mirror follows the reverberations of the Haitian Revolution in Cuba, where the violent entrenchment of slavery occurred at the very moment that the Haitian Revolution provided a powerful and proximate example of slaves destroying slavery. By creatively linking two stories – the story of the Haitian Revolution and that of the rise of Cuban slave society – that are usually told separately, Ada Ferrer sheds fresh light on both of these crucial moments in Caribbean and Atlantic history. Ada Ferrer is Professor of History and Latin American and Caribbean Studies at New York University. She is the author of Insurgent Cuba: Race, Nation, and Revolution, 1868–1898,whichwonthe2000 Berk- shire Book Prize for the best first book written by a woman in any field of history. Downloaded from Cambridge Books Online by IP 131.111.164.128 on Tue May 03 17:50:21 BST 2016. http://ebooks.cambridge.org/ebook.jsf?bid=CBO9781139333672 Cambridge Books Online © Cambridge University Press, 2016 Downloaded from Cambridge Books Online by IP 131.111.164.128 on Tue May 03 17:50:21 BST 2016. -

Abraham Lincoln, Kentucky African Americans and the Constitution

Abraham Lincoln, Kentucky African Americans and the Constitution Kentucky African American Heritage Commission Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Collection of Essays Abraham Lincoln, Kentucky African Americans and the Constitution Kentucky African American Heritage Commission Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Collection of Essays Kentucky Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Commission Kentucky Heritage Council © Essays compiled by Alicestyne Turley, Director Underground Railroad Research Institute University of Louisville, Department of Pan African Studies for the Kentucky African American Heritage Commission, Frankfort, KY February 2010 Series Sponsors: Kentucky African American Heritage Commission Kentucky Historical Society Kentucky Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Commission Kentucky Heritage Council Underground Railroad Research Institute Kentucky State Parks Centre College Georgetown College Lincoln Memorial University University of Louisville Department of Pan African Studies Kentucky Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Commission The Kentucky Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Commission (KALBC) was established by executive order in 2004 to organize and coordinate the state's commemorative activities in celebration of the 200th anniversary of the birth of President Abraham Lincoln. Its mission is to ensure that Lincoln's Kentucky story is an essential part of the national celebration, emphasizing Kentucky's contribution to his thoughts and ideals. The Commission also serves as coordinator of statewide efforts to convey Lincoln's Kentucky story and his legacy of freedom, democracy, and equal opportunity for all. Kentucky African American Heritage Commission [Enabling legislation KRS. 171.800] It is the mission of the Kentucky African American Heritage Commission to identify and promote awareness of significant African American history and influence upon the history and culture of Kentucky and to support and encourage the preservation of Kentucky African American heritage and historic sites. -

“I Wait for Me”: Visualizing the Absence of the Haitian Revolution in Cinematic Text by Jude Ulysse a Thesis Submitted in C

“I wait for me”: Visualizing the Absence of the Haitian Revolution in Cinematic Text By Jude Ulysse A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Social Justice Education Ontario Institute for Studies in Education University of Toronto 2017 ABSTRACT “I wait for me” Visualizing the Absence of the Haitian Revolution in Cinematic Text Doctor of Philosophy Department of Social Justice Education Ontario Institute for Studies in Education University of Toronto 2017 In this thesis I explore the memory of the Haitian Revolution in film. I expose the colonialist traditions of selective memory, the ones that determine which histories deserve the attention of professional historians, philosophers, novelists, artists and filmmakers. In addition to their capacity to comfort and entertain, films also serve to inform, shape and influence public consciousness. Central to the thesis, therefore, is an analysis of contemporary filmic representations and denials of Haiti and the Haitian Revolution. I employ a research design that examines the relationship between depictions of Haiti and the country’s colonial experience, as well as the revolution that reshaped that experience. I address two main questions related to the revolution and its connection to the age of modernity. The first concerns an examination of how Haiti has contributed to the production of modernity while the second investigates what it means to remove Haiti from this production of modernity. I aim to unsettle the hegemonic understanding of modernity as the sole creation of the West. The thrust of my argument is that the Haitian Revolution created the space where a re-articulation of the human could be possible.