An Investigation Into the Determining Factors of Zoo Visitor Attendances in UK Zoos

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

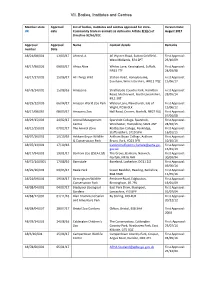

VII. Bodies, Institutes and Centres

VII. Bodies, Institutes and Centres Member state Approval List of bodies, institutes and centres approved for intra- Version Date: UK date Community trade in animals as defined in Article 2(1)(c) of August 2017 Directive 92/65/EEC Approval Approval Name Contact details Remarks number Date AB/21/08/001 13/03/17 Ahmed, A 46 Wyvern Road, Sutton Coldfield, First Approval: West Midlands, B74 2PT 23/10/09 AB/17/98/026 09/03/17 Africa Alive Whites Lane, Kessingland, Suffolk, First Approval: NR33 7TF 24/03/98 AB/17/17/005 15/06/17 All Things Wild Station Road, Honeybourne, First Approval: Evesham, Worcestershire, WR11 7QZ 15/06/17 AB/78/14/002 15/08/16 Amazonia Strathclyde Country Park, Hamilton First Approval: Road, Motherwell, North Lanarkshire, 28/05/14 ML1 3RT AB/29/12/003 06/04/17 Amazon World Zoo Park Watery Lane, Newchurch, Isle of First Approval: Wight, PO36 0LX 15/06/12 AB/17/08/065 08/03/17 Amazona Zoo Hall Road, Cromer, Norfolk, NR27 9JG First Approval: 07/04/08 AB/29/15/003 24/02/17 Animal Management Sparsholt College, Sparsholt, First Approval: Centre Winchester, Hampshire, SO21 2NF 24/02/15 AB/12/15/001 07/02/17 The Animal Zone Rodbaston College, Penkridge, First Approval: Staffordshire, ST19 5PH 16/01/15 AB/07/16/001 10/10/16 Askham Bryan Wildlife Askham Bryan College, Askham First Approval: & Conservation Park Bryan, York, YO23 3FR 10/10/16 AB/07/13/001 17/10/16 [email protected]. First Approval: gov.uk 15/01/13 AB/17/94/001 19/01/17 Banham Zoo (ZSEA Ltd) The Grove, Banham, Norwich, First Approval: Norfolk, NR16 -

Lent Term 2007

CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY RAMBLING CLUB Lent Term 2007 Welcome back to the Rambling Club. Once again, we invite you to leave the city for a few hours this term, and enjoy the surrounding countryside with us. The pace of our walks is generally easy, as our main aim is to relax and appreciate the local scenery and villages, and we have tried to provide a mixture of walks of different lengths. We usually stop at a village pub en route, but you should bring a packed lunch and a drink anyway as occasionally a walk doesn’t pass a pub, or we find that a pub is closed. Strong boots and waterproof clothing are also recommended. Your only expense is the bus or train fare (given below), plus our £1 annual membership fee. There is no need to sign up in advance to join any of this term’s walks – just turn up at the time and place given. Our meeting points are: Bus/Coach: At the corner of Drummer Street and Emmanuel Street. Train: In the main hall of Cambridge Railway Station. Saturday 20th January: "Swanning around Swavesey" Swavesey Circular 9 miles Contact: Steven For the first walk of term we head to the village of Swavesey, situated close to the River Ouse about 10 miles north-west of Cambridge. From here we'll explore the lakes and waterways of the nearby Fen Drayton Nature Reserve before visiting the village of Fenstanton. After lunch we'll walk along part of the River Ouse on our way back towards Swavesey for the bus home. -

Verzeichnis Der Europäischen Zoos Arten-, Natur- Und Tierschutzorganisationen

uantum Q Verzeichnis 2021 Verzeichnis der europäischen Zoos Arten-, Natur- und Tierschutzorganisationen Directory of European zoos and conservation orientated organisations ISBN: 978-3-86523-283-0 in Zusammenarbeit mit: Verband der Zoologischen Gärten e.V. Deutsche Tierpark-Gesellschaft e.V. Deutscher Wildgehege-Verband e.V. zooschweiz zoosuisse Schüling Verlag Falkenhorst 2 – 48155 Münster – Germany [email protected] www.tiergarten.com/quantum 1 DAN-INJECT Smith GmbH Special Vet. Instruments · Spezial Vet. Geräte Celler Str. 2 · 29664 Walsrode Telefon: 05161 4813192 Telefax: 05161 74574 E-Mail: [email protected] Website: www.daninject-smith.de Verkauf, Beratung und Service für Ferninjektionsgeräte und Zubehör & I N T E R Z O O Service + Logistik GmbH Tranquilizing Equipment Zootiertransporte (Straße, Luft und See), KistenbauBeratung, entsprechend Verkauf undden Service internationalen für Ferninjektionsgeräte und Zubehör Vorschriften, Unterstützung bei der Beschaffung der erforderlichenZootiertransporte Dokumente, (Straße, Vermittlung Luft und von See), Tieren Kistenbau entsprechend den internationalen Vorschriften, Unterstützung bei der Beschaffung der Celler Str.erforderlichen 2, 29664 Walsrode Dokumente, Vermittlung von Tieren Tel.: 05161 – 4813192 Fax: 05161 74574 E-Mail: [email protected] Str. 2, 29664 Walsrode www.interzoo.deTel.: 05161 – 4813192 Fax: 05161 – 74574 2 e-mail: [email protected] & [email protected] http://www.interzoo.de http://www.daninject-smith.de Vorwort Früheren Auflagen des Quantum Verzeichnis lag eine CD-Rom mit der Druckdatei im PDF-Format bei, welche sich großer Beliebtheit erfreute. Nicht zuletzt aus ökologischen Gründen verzichten wir zukünftig auf eine CD-Rom. Stattdessen kann das Quantum Verzeichnis in digitaler Form über unseren Webshop (www.buchkurier.de) kostenlos heruntergeladen werden. Die Datei darf gerne kopiert und weitergegeben werden. -

Sitting Pretty: Endangered Species Get New Enclosures

EDF 4175_PLUGGED IN 6.15_21.qxp_EDF 06/08/2015 15:17 Page 1 PAugust 20l15 uggeto nucleadr new build at iHinknley Point C Sitting pretty: Endangered species get new enclosures Inside this issue of Plugged in : Good news for businesses: New facilities and ongoing support ............................................4-6 Broadening horizons: Education programme Inspires ..............................................................10-11 Community funding: The story so far ......................................................................................................12 STOP PRESS HPC preferred bidders announced EDF 4175_PLUGGED IN 6.15_21.qxp_EDF 06/08/2015 15:17 Page 2 Plugged in / August 2015 News Notes from Nigel Steady progress as we near Final Investment Decision progress with all parties and anticipate a Final STOP Investment Decision in the coming months, after which we can remobilse and start the earthworks PRESS! proper. You may have read about an Austrian challenge to the European Commission’s state aid decision still need to be addressed, but we EDF Energy are confident that these robust agreements will announces continue to withstand any challenge. further preferred We were pleased to be able to announce this bidders for the week our list of preferred bidders for a number Under difficult circumstances, the HPC of the large contracts for HPC. This is good news Hinkley Point C project has made some great strides over for the project and for businesses as we estimate project the last few months. Highways that the value of work to the UK will exceed our improvement works are progressing well: original estimate of 57%. It’s also excellent news EDF Energy has announced the the busy Taunton Road and Broadway for our county with five preferred bidders for selection of further preferred junctions in Bridgwater have been large contracts being Somerset-based bidders for the Hinkley Point C completed ahead of schedule and the consortiums, established to serve the project: project. -

ATIC0943 {By Email}

Animal and Plant Health Agency T 0208 2257636 Access to Information Team F 01932 357608 Weybourne Building Ground Floor Woodham Lane www.gov.uk/apha New Haw Addlestone Surrey KT15 3NB Our Ref: ATIC0943 {By Email} 4 October 2016 Dear PROVISION OF REQUESTED INFORMATION Thank you for your request for information about zoos which we received on 26 September 2016. Your request has been handled under the Freedom of Information Act 2000. The information you requested and our response is detailed below: “Please can you provide me with a full list of the names of all Zoos in the UK. Under the classification of 'Zoos' I am including any place where a member of the public can visit or observe captive animals: zoological parks, centres or gardens; aquariums, oceanariums or aquatic attractions; wildlife centres; butterfly farms; petting farms or petting zoos. “Please also provide me the date of when each zoo has received its license under the Zoo License act 1981.” See Appendix 1 for a list that APHA hold on current licensed zoos affected by the Zoo License Act 1981 in Great Britain (England, Scotland and Wales), as at 26 September 2016 (date of request). The information relating to Northern Ireland is not held by APHA. Any potential information maybe held with the Department of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs Northern Ireland (DAERA-NI). Where there are blanks on the zoo license start date that means the information you have requested is not held by APHA. Please note that the Local Authorities’ Trading Standard departments are responsible for administering and issuing zoo licensing under the Zoo Licensing Act 1981. -

ZSL Conservation Review 2017-18

CONSERVATION REVIEW 2017-18 CONSERVATION ZSL Conservation Review | 2017-18 Front cover: ZSL is working to conserve tigers Below: in Indonesia, our work protects CONTENTS in Indonesia, Nepal, Thailand and Russia forest wildlife such as the rhinoceros hornbill Welcome 3 ZSL 200: Our vision and purpose 4 ZSL’s global impact 6 Introduction 8 Our impacts Saving threatened species 11 Protecting and restoring habitats 17 Inspiring, informing and empowering conservation action 25 Funders, partners and governance Funders 31 Partners 32 Governance 34 2 ZSL Conservation Review 2017-18 zsl.org WELCOME Welcome Professor Sir John Beddington, the President of The Zoological Society of London, introduces our Conservation Review for May 2017 until April 2018. s President of The Zoological Society of London (ZSL), example, we established that micro-communities of bacteria on I am pleased to present our Conservation Review amphibian skin could confer immunity to the fungus that is causing 2017-18. Every year I am impressed by the breadth chytridiomycosis and is driving global amphibian declines. We are also and impact of the work our organisation undertakes, empowering wildlife veterinarians around the world via our MSc courses and by the unique set of skills and resources we employ in wildlife health and wildlife biology, and our Wildlife Health Bridge Ato conserve the natural world. ZSL delivers science-driven, innovative programme with the Wildlife Institute of India. Our vets are supporting conservation projects in the field, and effective engagement with projects that alleviate the conflicts between wildlife and people in the audiences ranging from the general public to global policymakers. -

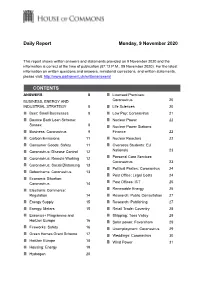

Daily Report Monday, 9 November 2020 CONTENTS

Daily Report Monday, 9 November 2020 This report shows written answers and statements provided on 9 November 2020 and the information is correct at the time of publication (07:12 P.M., 09 November 2020). For the latest information on written questions and answers, ministerial corrections, and written statements, please visit: http://www.parliament.uk/writtenanswers/ CONTENTS ANSWERS 8 Licensed Premises: BUSINESS, ENERGY AND Coronavirus 20 INDUSTRIAL STRATEGY 8 Life Sciences 20 Beer: Small Businesses 8 Low Pay: Coronavirus 21 Bounce Back Loan Scheme: Nuclear Power 22 Sussex 8 Nuclear Power Stations: Business: Coronavirus 9 Finance 22 Carbon Emissions 11 Nuclear Reactors 22 Consumer Goods: Safety 11 Overseas Students: EU Coronavirus: Disease Control 12 Nationals 23 Coronavirus: Remote Working 12 Personal Care Services: Coronavirus 23 Coronavirus: Social Distancing 13 Political Parties: Coronavirus 24 Debenhams: Coronavirus 13 Post Office: Legal Costs 24 Economic Situation: Coronavirus 14 Post Offices: ICT 25 Electronic Commerce: Renewable Energy 25 Regulation 14 Research: Public Consultation 27 Energy Supply 15 Research: Publishing 27 Energy: Meters 15 Retail Trade: Coventry 28 Erasmus+ Programme and Shipping: Tees Valley 28 Horizon Europe 16 Solar power: Faversham 29 Fireworks: Safety 16 Unemployment: Coronavirus 29 Green Homes Grant Scheme 17 Weddings: Coronavirus 30 Horizon Europe 18 Wind Power 31 Housing: Energy 19 Hydrogen 20 CABINET OFFICE 31 Musicians: Coronavirus 44 Ballot Papers: Visual Skateboarding: Coronavirus 44 Impairment 31 -

Greater Cambridge Partnership Executive Board

GREATER CAMBRIDGE PARTNERSHIP EXECUTIVE BOARD 4:00 pm Thursday 27th June 2019 Kreis Viersen Room Shire Hall Cambridge AGENDA PAGE NUMBER 1. Election of Chairperson ( - ) 2. Appointment of Vice Chairperson ( - ) 3. Apologies for Absence ( - ) 4. Declaration of Interests ( - ) 5. Minutes (3-15) 6. Public Questions (16) 7. Feedback from the Joint Assembly (17-20) 8. City Access and Public Transport Improvements (21-160) 9. West of Cambridge Package - Cambridge South West Travel Hub (161-171) 10. Cambridge South East Transport Scheme (172-192) 11. Cambridgeshire Rail Corridor Study (193-198) 12. Quarterly Progress Report (199-216) 13. Date of Next Meeting ( - ) 4:00 pm Thursday 3rd October 2019 at South Cambridgeshire Hall, Cambourne Page 1 of 219 MEMBERSHIP The Executive Board comprises the following members: Councillor Lewis Herbert - Cambridge City Council Councillor Ian Bates - Cambridgeshire County Council Councillor Aiden Van de Weyer - South Cambridgeshire District Council Claire Ruskin - Business Representative Phil Allmendinger - University Representative The Greater Cambridge Partnership is committed to open government and members of the public are welcome to attend Executive Board meetings. Meetings are live streamed and can be accessed from the GCP Facebook page: www.facebook.com/GreaterCam. We support the principle of transparency and encourage filming, recording and taking photographs at meetings that are open to the public. We also welcome the use of social networking and micro-blogging websites (such as Twitter and Facebook) to communicate with people about what’s happening, as it happens. For more information about this meeting, please contact Nicholas Mills (Cambridgeshire County Council Democratic Services) on 01223 699763 or via e-mail at [email protected]. -

30 Shepreth Road | Barrington | Cambridge | CB22 7SB

30 Shepreth Road | Barrington | Cambridge | CB22 7SB A truly superb contemporary architect designed home THE PROPERTY appreciate the idyllic setting. Open tread staircases with extending to over 3,200sqft set in secluded grounds of over 30 Shepreth Road is a stunning, modern village home glass balustrades separate each floor which again one acre with unrivalled country views. Stylish and constructed to a bespoke and unique design. The beautifully accentuates the light and airy feel to the house. beautifully presented accommodation imaginatively built finished and stylish accommodation extends to over On the ground floor there is a beautiful fully fitted kitchen over three floors. 3,200sqft and is imaginatively laid out over three floors. It is with breakfast bar, excellent range of laminate fronted walk based on an open plan design to the main living areas and base units, Neff appliances, water softener and boiling Reception hallway, open plan kitchen, breakfast/diner and balanced perfectly with separate and versatile reception tap fridge and freezer and dishwasher. The kitchen is open sitting room, 2/3 further reception rooms, cloakroom, rooms. The emphasis is on the views to the rear and plan to the dining space with a feature wall partially laundry/utility room, 4/5 bedrooms, 3 bathrooms, wine practical easy living along with huge levels of natural light separately this space from the family room with cellar, gravelled driveway and extensive parking, detached and a feeling of space. Every care has been taken to freestanding wood burner. There are also two further garage and workshop, established gardens and two private maximise the position and outlook along with superb reception rooms and a cloakroom. -

Brook Barn, 9 Angle Lane Shepreth SG8 6QJ

NEWLY BUILT 2,624 SQ FT DETACHED REED THATCHED BARN STYLE VILLAGE HOUSE Brook Barn, 9 Angle Lane Shepreth SG8 6QJ Freehold A newly built 2,624 sq ft detached reed thatched barn style village house with double garage Brook Barn, 9 Angle Lane Shepreth SG8 6QJ Freehold Entrance hall ◆ Large sitting room ◆ garden room/study ◆ dining room/family room ◆ kitchen/breakfast room ◆ utility ◆ 4 bedroom suites ◆ detached double garage ◆ gardens ◆ EPC rating = B Situation Brook Barn is situated at the end of Angle Lane towards the edge of this popular south Cambridgeshire village. Shepreth is approximately 9 miles from the high tech university city of Cambridge and 6 miles from the market town of Royston in Hertfordshire. The A10 passes to the west of the village which provides direct access to the M11 at Junction 11 on the southern side of Cambridge, the A505 on the outskirts of Royston and London is approximately 51 miles to the south. There are fast and regular train services from Royston to London Kings Cross taking from 37 minutes. Train services are also available from nearby Shepreth station which provides services to Cambridge (from 14 min), London (from 54 min) and Royston (8 min). Local shopping facilities are available in Meldreth, Barrington and Melbourn with a Tesco superstore on the edge of Royston and Waitrose at Trumpington. The village has two pub/restaurants, a tea shop and a small zoo – Shepreth Wildlife Park. Comprehensive shopping, recreational and cultural facilities are available in Cambridge including the Grand Arcade shopping mall. There are schools for all ages in the area with primary schools at Meldreth and Barrington and secondary schooling at Melbourn Village College. -

Visitor Attraction Trends England 2003 Presents the Findings of the Survey of Visits to Visitor Attractions Undertaken in England by Visitbritain

Visitor Attraction Trends England 2003 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS VisitBritain would like to thank all representatives and operators in the attraction sector who provided information for the national survey on which this report is based. No part of this publication may be reproduced for commercial purp oses without previous written consent of VisitBritain. Extracts may be quoted if the source is acknowledged. Statistics in this report are given in good faith on the basis of information provided by proprietors of attractions. VisitBritain regrets it can not guarantee the accuracy of the information contained in this report nor accept responsibility for error or misrepresentation. Published by VisitBritain (incorporated under the 1969 Development of Tourism Act as the British Tourist Authority) © 2004 Bri tish Tourist Authority (trading as VisitBritain) Cover images © www.britainonview.com From left to right: Alnwick Castle, Legoland Windsor, Kent and East Sussex Railway, Royal Academy of Arts, Penshurst Place VisitBritain is grateful to English Heritage and the MLA for their financial support for the 2003 survey. ISBN 0 7095 8022 3 September 2004 VISITOR ATTR ACTION TRENDS ENGLAND 2003 2 CONTENTS CONTENTS A KEY FINDINGS 4 1 INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND 12 1.1 Research objectives 12 1.2 Survey method 13 1.3 Population, sample and response rate 13 1.4 Guide to the tables 15 2 ENGLAND VISIT TRENDS 2002 -2003 17 2.1 England visit trends 2002 -2003 by attraction category 17 2.2 England visit trends 2002 -2003 by admission type 18 2.3 England visit trends -

Somerset Routes

Minehead Dunster Blue Anchor Washford Clevedon Clevedon Tyntesfield Oakham Station Station Station Station Lambretta Weston-Super-Mare (Wraxall)Treasures Exmoor Classic West Somerset Scooter Museum Pier Court Car Collection Rural Life Museum Museum (W-s-M) (Portbury) (Porlock) (Allerford) Helicopter Stogursey Castle Kilve Chantry Nether Stowey Castle Brean Down Museum (W-s-M) & Fort Coleridge Cottage Minehead Dunster WorkingDunster CastleDunster DollsBlue Anchor Somerset &Cleeve Dorset Abbey (Nether Stowey) Water Mill Museum Railway MuseumRailway Museum(Washford) Museum of MethodismDovery Manor HolnicoteBurgundy Estate Chapel (Selworthy) (Washford) Burnham-on-Sea From Bristol in West Somerset (Porlock)Museum (Porlock) Watchet Axbridge & Lighthouse District Museum Market House (King John’s Dolebury Warren Museum Brent Knoll Hunting Lodge) Hill Fort Blake Museum Hill Fort Cheddar Caves & Gorge: West Somerset Mineral Railway Watchet (Bridgwater) Museum of Prehistory (Brendon Hills) Boat Museum Somerset Brick Watchet & Tile Museum Ashton Windmill Charterhouse (Bridgwater) Farleigh Hungerford Washford Radio Museum Barford (at Tropiquaria) Sweets Peat and Priddy Barrows Castle Park Westonzoyland Combe Sydenham Hall Pumping Station Science Museum Mells From North Devon Bakelite Museum (Enmore) & Country Park (Monksilver) Fyne Court Museum Wookey (Williton) Frome Museum (Broomfield) Hole Caves West Somerset Railway Battle of Abbot’s Fish & Museum Nunney Castle Cothay Manor and Gardens (Bishops Lydeard) Water Mill & Hestercombe Sedgemoor House