The Judicial Bookshelf D Grier F

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Political Effects of the Addition of Judgeships to the United States Supreme Court Following Electoral Realignments

A Compliant Court: The Political Effects of the Addition of Judgeships to the United States Supreme Court Following Electoral Realignments Lauren Paige Joyce Judson Thesis submitted to the faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Arts In Political Science Jason P. Kelly, Chair Wayne D. Moore Karen M. Hult August 7, 2014 Blacksburg, Virginia Keywords: Judicial Politics, Electoral Realignment, Alteration to the Supreme Court Copyright 2014, Lauren J. Judson A Compliant Court: The Political Effects of the Addition of Judgeships to the United States Supreme Court Following Electoral Realignments Lauren J. Judson ABSTRACT During periods of turmoil when ideological preferences between the federal branches of government fail to align, the relationship between the three quickly turns tumultuous. Electoral realignments especially have the potential to increase tension between the branches. When a new party replaces the “old order” in both the legislature and the executive branches, the possibility for conflict emerges with the Court. Justices who make decisions based on old regime preferences of the party that had appointed them to the bench will likely clash with the new ideological preferences of the incoming party. In these circumstances, the president or Congress may seek to weaken the influence of the Court through court-curbing methods. One example Congress may utilize is changing the actual size of the Supreme The size of the Supreme Court has increased four times in United States history, and three out of the four alterations happened after an electoral realignment. Through analysis of Supreme Court cases, this thesis seeks to determine if, after an electoral realignment, holdings of the Court on issues of policy were more congruent with the new party in power after the change in composition as well to examine any change in individual vote tallies of the justices driven by the voting behavior of the newly appointed justice(s). -

Justice Under Law William F

College of William & Mary Law School William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository Popular Media Faculty and Deans 1977 Justice Under Law William F. Swindler William & Mary Law School Repository Citation Swindler, William F., "Justice Under Law" (1977). Popular Media. 264. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/popular_media/264 Copyright c 1977 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/popular_media INL Chief Justice John Marshall, portrayed by Edward Holmes, is the star of the P.B.S. "Equal Justice under Law" series. By William F. Swindler T HEBuilding-"Equal MOTTO on the Justice facade under of-the Law"-is Supreme also Court the title of a series of five films that will have their pre- mieres next month on the Public Broadcasting Service network. Commissioned by the Bicentennial Committee of the Judicial Conference of the United States and produced for public television by the P.B.S. national production center at WQED, Pittsburgh, the films are intended to inform the general public, as well as educational and professional audiences, on the American constitutional heritage as exemplified in the major decisions of the Supreme Court under Chief Justice John Marshall. ABOVE: Marshall confers with Justice Joseph Story (left) and Jus- Four constitutional cases are dramatized in the tice Bushrod Washington (right). BELOW: Aaron Burr is escorted to series-including the renowned judicial review issue jail. in Marbury v. Madison in 1803, the definition of "nec- essary and proper" powers of national government in the "bank case" (McCulloch v. -

Justice William Cushing and the Treaty-Making Power

Vanderbilt Law Review Volume 10 Issue 2 Issue 2 - February 1957 Article 9 2-1957 Justice William Cushing and the Treaty-Making Power F. William O'Brien S.J. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, and the Supreme Court of the United States Commons Recommended Citation F. William O'Brien S.J., Justice William Cushing and the Treaty-Making Power, 10 Vanderbilt Law Review 351 (1957) Available at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr/vol10/iss2/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vanderbilt Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JUSTICE WILLIAM CUSHING AND THE TREATY-MAKING POWER F. WILLIAM O'BRIEN, S.J.* Washington's First Appointees Although the work of the Supreme Court during the first few years was not great if measured in the number of cases handled, it would be a mistake to conclude that the six men who sat on the Bench during this formative period made no significant contribution to the develop- ment of American constitutional law. The Justices had few if any precedents to use as guides, and therefore their judicial work, limited though it was in volume, must be considered as stamped with the significance which attaches to all pioneer activity. Moreover, most of this work was done while on circuit duty in the different districts, and therefore from Vermont to Georgia the Supreme Court Justices were emissaries of good will for the new Constitution and the recently established general government. -

Keep Reading Wilson As a Justice

Wilson as a Justice MAEVA MARCUS* ABSTRACT James Wilson, a founding father of great intellect and promise, never ful®lled his potential as a Justice. This paper explores his experience on the Supreme Court and the reasons that led to his failure to achieve the distinction that was expected of him. James Wilson very much wanted to be the ®rst Chief Justice.1 But when George Washington denied him that honor and nominated him to be an Associate Justice, he accepted and threw himself into the work with characteristic industry.2 Other than a title and $500 more in annual salary3 (Wilson probably wanted this more than anything else), Wilson lost little. Life as an Associate Justice would be no different from life as the Chief. A Justice occupied one of the most exalted positions in the new government and was paid more than any other federal em- ployee, except the President and the Vice-President.4 Nominations were the sub- ject of ®erce competition.5 But in 1789 no one knew exactly what that job would entail. This paper gives the reader some idea of what a Justice, and speci®cally James Wilson, did in the 1790s.6 Wilson spent more of his time on the bench of circuit courts than he did on the Supreme Court bench; thus, this paper will focus signi®- cantly on his circuit court activities.7 And Wilson performed his circuit court * Currently Director of the Institute for Constitutional History at the New-York Historical Society and Research Professor at the George Washington University Law School and General Editor of the Oliver Wendell Holmes Devise History of the Supreme Court of the United States, Maeva Marcus previously edited The Documentary History of the Supreme Court of the United States, 1789-1800, an eight-volume series completed in 2006. -

Biden Holds Steady, Warren Slips As the Iowa Caucuses Approach

ABC NEWS/WASHINGTON POST POLL: 2020 Democrats EMBARGOED FOR RELEASE AFTER 12:01 a.m. Sunday, Jan. 26, 2020 Biden Holds Steady, Warren Slips As the Iowa Caucuses Approach Joe Biden’s holding his ground in preference nationally for the 2020 Democratic presidential nomination, with Bernie Sanders close by and a drop in support for Elizabeth Warren. Two new arrivals to the leaderboard come next in the latest ABC News/Washington Post poll: Mike Bloomberg and Andrew Yang. With the Feb. 3 Iowa caucuses drawing near, 77 percent of Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents nationally say they’re satisfied with their choice of candidates. Far fewer, 24 percent, are very satisfied, although that’s near the average in ABC/Post polls since 2000. This poll, produced for ABC by Langer Research Associates, finds plenty of room for movement: Just about half of leaned Democrats are very enthusiastic about their choice, and 53 percent say they’d consider supporting a different candidate. Warren, while weaker as a first choice, leads in second-choice preference. Further, while Biden continues to prevail by a wide margin as the candidate with the best chance to defeat Donald Trump in the general election, his score on the measure has slipped slightly, from 45 percent in July to 38 percent now. Eighteen percent pick Sanders as best against Trump; 10 percent, Warren. Biden does best in vote preference among likely voters, defined here as those who say they’re registered and certain to vote in their state’s primary or caucuses. He has 34 percent support in this group, leading Sanders, at 22 percent, and Warren, 14 percent. -

Supreme Court Justices

The Supreme Court Justices Supreme Court Justices *asterick denotes chief justice John Jay* (1789-95) Robert C. Grier (1846-70) John Rutledge* (1790-91; 1795) Benjamin R. Curtis (1851-57) William Cushing (1790-1810) John A. Campbell (1853-61) James Wilson (1789-98) Nathan Clifford (1858-81) John Blair, Jr. (1790-96) Noah Haynes Swayne (1862-81) James Iredell (1790-99) Samuel F. Miller (1862-90) Thomas Johnson (1792-93) David Davis (1862-77) William Paterson (1793-1806) Stephen J. Field (1863-97) Samuel Chase (1796-1811) Salmon P. Chase* (1864-73) Olliver Ellsworth* (1796-1800) William Strong (1870-80) ___________________ ___________________ Bushrod Washington (1799-1829) Joseph P. Bradley (1870-92) Alfred Moore (1800-1804) Ward Hunt (1873-82) John Marshall* (1801-35) Morrison R. Waite* (1874-88) William Johnson (1804-34) John M. Harlan (1877-1911) Henry B. Livingston (1807-23) William B. Woods (1881-87) Thomas Todd (1807-26) Stanley Matthews (1881-89) Gabriel Duvall (1811-35) Horace Gray (1882-1902) Joseph Story (1812-45) Samuel Blatchford (1882-93) Smith Thompson (1823-43) Lucius Q.C. Lamar (1883-93) Robert Trimble (1826-28) Melville W. Fuller* (1888-1910) ___________________ ___________________ John McLean (1830-61) David J. Brewer (1890-1910) Henry Baldwin (1830-44) Henry B. Brown (1891-1906) James Moore Wayne (1835-67) George Shiras, Jr. (1892-1903) Roger B. Taney* (1836-64) Howell E. Jackson (1893-95) Philip P. Barbour (1836-41) Edward D. White* (1894-1921) John Catron (1837-65) Rufus W. Peckham (1896-1909) John McKinley (1838-52) Joseph McKenna (1898-1925) Peter Vivian Daniel (1842-60) Oliver W. -

2-8-20 Final NH Tracking Cross Tabs

Table Q5 Page 1 5. I'm going to read you a list of the major active candidates who are certified on the New Hampshire Democratic ballot for president. Please tell me who you would vote for or lean toward at this point. If you know who you would vote for, feel free to stop me at any time. BANNER 1 =============================================================================================== DEMOGRAPHICS ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- LIKELY TO GENDER AREA PARTY VOTE AGE ----------- ---------------------- ----------------- ----------- ----------------------------- FE- WEST/ CEN- HILLS ROCKI IND/ NOT OVER TOTAL MALE MALE NORTH TRAL BORO NGHAM DEM UNDCL REG VERY SMWT 18-35 36-45 46-55 56-65 65 ----- ----- ----- ----- ----- ----- ----- ----- ----- ----- ----- ----- ----- ----- ----- ----- ----- Total 500 220 280 126 130 133 111 298 197 2 461 39 132 87 93 99 82 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 Michael Bennet 1 1 - - - 1 - 1 - - 1 - - - - 1 - * * 1 * * 1 Joe Biden 52 19 33 15 13 15 9 38 14 - 48 4 5 5 8 18 16 10 9 12 12 10 11 8 13 7 10 10 4 6 9 18 20 Pete Buttigieg 109 50 59 17 36 31 25 61 48 - 100 9 25 18 25 24 13 22 23 21 13 28 23 23 20 24 22 23 19 21 27 24 16 Tulsi Gabbard 10 7 3 3 1 6 - 4 6 - 9 1 3 2 1 2 2 2 3 1 2 1 5 1 3 2 3 2 2 1 2 2 Amy Klobuchar 43 18 25 12 11 10 10 22 20 - 41 2 4 4 13 12 10 9 8 9 10 8 8 9 7 10 9 5 3 5 14 12 12 Deval Patrick 2 2 - 1 - - 1 2 - - 1 1 - 1 - 1 - * 1 1 1 1 * 3 1 1 Bernie Sanders 119 58 61 41 28 25 25 66 51 -

Voter Intent Posters

envelope Democratic Sort 2 Mark one party declaration box (required) Democratic Party X decare that m art preference i the Democratic Part an wil not Tabulate articiate i the nomiatio roce o an other politica art for the 202 Presidentia election. Republican Party decare that am a Republica an have not particiate an wil not articiate i the 202 precict caucu or conventio system o an other arty. Declared-party Ballot, Declared-party Ballot, Declared-party Ballot ballot Write-in ballot Overvote ballot Deocratic Party Republican Party Deocratic Party Republican Party Deocratic Party Republican Party I you ared Deocratic Party on I you ared Republican Party on I you ared Deocratic Party on I you ared Republican Party on I you ared Deocratic Party on I you ared Republican Party on your return envelope, you ust vote your return envelope, you ust vote your return envelope, you ust vote your return envelope, you ust vote your return envelope, you ust vote your return envelope, you ust vote or O Deocratic candidate below. or O Republican candidate below. or O Deocratic candidate below. or O Republican candidate below. or O Deocratic candidate below. or O Republican candidate below. icae eet Doa Trm icae eet Doa Trm icae eet Doa Trm oe ie __________________________ oe ie __________________________ oe ie __________________________ icae oomer icae oomer icae oomer or ooer or ooer or ooer ete ttiie ete ttiie ete ttiie o Deae o Deae o Deae i aar i aar i aar m ocar m ocar m ocar Dea atric Dea atric Dea atric erie Saer erie Saer erie Saer om Steer om Steer om Steer iaet arre iaet arre iaet arre re a re a re a committe Deeate committe Deeate committe Deeate __________________________ __________________________A. -

And I'm Calling from RKM Research and Communications

Franklin Pierce University / Boston Herald / NBC10 Poll © 2020 RKM Research and Communications (1/23/-1/26) INT1 Hello, my name is ___________, and I'm calling from RKM Research and Communications. We’re conducting a very brief opinion poll on behalf of Franklin Pierce University, the Boston Herald, and NBC10 TV news and I’d like to speak to an adult age 18 or older. “Would that be you?” or “Is he / she available?” Type [next] to continue INT2 I assure you that this is not a sales call. We’re only interested in your opinions. Thank you for helping us. Your telephone number was chosen randomly, and all of your responses are completely confidential and anonymous. 01 Eligible respondent [continue] 02 Appointment [setup a call-back] 99 Refusal [thank and terminate] Q01 Are you currently registered to vote in New Hampshire? IF YES: Are you registered as a Democrat, independent, Republican, or something else? 00 No - not registered [thank and terminate] 01 Democrat [continue] 02 independent, or undeclared [continue] 03 Republican [continue] 88 Other [thank and terminate] 99 Do NOT live in New Hampshire [thank and terminate] 1 Q02 How likely is it that you will vote in the upcoming New Hampshire presidential primary? Do you think you: Read responses: 01 Definitely will [continue] 02 Probably will [continue] 03 You’re not sure yet [thank and terminate] 04 You probably won’t [thank and terminate] [If Q01 = 2 or Q01 = 88, skip to Q03]: [if Q01 = 1 or 3, skip to Q04] Q03 Do you plan to vote in the Democratic or Republican presidential primary? 01 Democratic [skip to Q04] 02 Republican [skip to Q04] 88 Other [thank and terminate] 99 Don=t know / unsure [thank and terminate] Q04 How closely have you followed the 2020 presidential race? Would you say: Read responses: 01 Very closely 02 Moderately closely 03 Only somewhat closely 99 Don’t know / unsure 2 [If Democratic primary voter: Q01 = 1 or Q03 = 1] ASK Q05 – Q19: Q05 Now I am going to read you a list of some candidates who are running in the Democratic presidential primary. -

Biden and Warren Trail 2/9/2020

CNN 2020 NH Primary Poll February 9, 2020 SANDERS'S LEAD OVER BUTTIGIEG IN NH HOLDING STEADY; BIDEN AND WARREN TRAIL By: Sean P. McKinley, M.A. [email protected] Zachary S. Azem, M.A. 603-862-2226 Andrew E. Smith, Ph.D. cola.unh.edu/unh-survey-center DURHAM, NH – With three days of campaigning le before the votes are counted in New Hampshire, Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders maintains a slim lead over former South Bend (IN) Mayor Pete Bu gieg among likely Democra c voters. Former Vice President Joe Biden and Massachuse s Senator Elizabeth Warren con nue to trail, with Minnesota Senator Amy Klobuchar, Hawaii Congresswoman Tulsi Gabbard, and entrepreneur Andrew Yang further back. Klobuchar has experienced a slight up ck in support since the last polling period and now sits in fi h place. Sanders con nues to hold a sizeable lead among self-described liberal likely Democra c voters while Bu gieg leads among moderates and conserva ves. These findings are based on the latest CNN 2020 New Hampshire Primary Poll*, conducted by the University of New Hampshire Survey Center. Seven hundred sixty-five (765) randomly selected New Hampshire adults were interviewed in English by landline and cellular telephone between February 5 and February 8, 2020. The margin of sampling error for the survey is +/- 3.5 percent. Included in the sample were 384 likely 2020 Democra c Primary voters (margin of sampling error +/- 5.0 percent) and 227 likely 2020 Republican Primary voters (margin of sampling error +/- 6.5 percent). Trend points prior to July 2019 reflect results from the Granite State Poll, conducted by the University of New Hampshire Survey Center. -

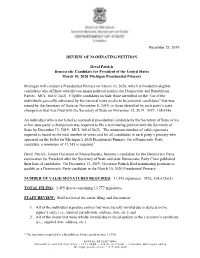

December 23, 2019 REVIEW of NOMINATING PETITION Deval

December 23, 2019 REVIEW OF NOMINATING PETITION Deval Patrick Democratic Candidate for President of the United States March 10, 2020 Michigan Presidential Primary Michigan will conduct a Presidential Primary on March 10, 2020, which is limited to eligible candidates who affiliate with the two major political parties, the Democratic and Republican Parties. MCL 168.613a(2). Eligible candidates include those identified on the “list of the individuals generally advocated by the national news media to be potential candidates” that was issued by the Secretary of State on November 8, 2019, or those identified by each party’s state chairperson that was filed with the Secretary of State on November 12, 2019. MCL 168.614a. An individual who is not listed as a potential presidential candidate by the Secretary of State or his or her state party’s chairperson was required to file a nominating petition with the Secretary of State by December 13, 2019. MCL 168.615a(2). The minimum number of valid signatures required is based on the total number of votes cast for all candidates in each party’s primary who appeared on the ballot for Michigan’s 2016 Presidential Primary: for a Democratic Party candidate, a minimum of 11,345 is required.1 Deval Patrick, former Governor of Massachusetts, became a candidate for the Democratic Party nomination for President after the Secretary of State and state Democratic Party Chair published their lists of candidates. On December 13, 2019, Governor Patrick filed nominating petitions to qualify as a Democratic Party candidate in the March 10, 2020 Presidential Primary. -

The Constitution in the Supreme Court: the Powers of the Federal Courts, 1801-1835 David P

The Constitution in the Supreme Court: The Powers of the Federal Courts, 1801-1835 David P. Curriet In an earlier article I attempted to examine critically the con- stitutional work of the Supreme Court in its first twelve years.' This article begins to apply the same technique to the period of Chief Justice John Marshall. When Marshall was appointed in 1801 the slate was by no means clean; many of our lasting principles of constitutional juris- prudence had been established by his predecessors. This had been done, however, in a rather tentative and unobtrusive manner, through suggestions in the seriatim opinions of individual Justices and through conclusory statements or even silences in brief per curiam announcements. Moreover, the Court had resolved remark- ably few important substantive constitutional questions. It had es- sentially set the stage for John Marshall. Marshall's long tenure divides naturally into three periods. From 1801 until 1810, notwithstanding the explosive decision in Marbury v. Madison,2 the Court was if anything less active in the constitutional field than it had been before Marshall. Only a dozen or so cases with constitutional implications were decided; most of them concerned relatively minor matters of federal jurisdiction; most of the opinions were brief and unambitious. Moreover, the cast of characters was undergoing rather constant change. Of Mar- shall's five original colleagues, William Cushing, William Paterson, Samuel Chase, and Alfred Moore had all been replaced by 1811.3 From the decision in Fletcher v. Peck4 in 1810 until about 1825, in contrast, the list of constitutional cases contains a succes- t Harry N.