On the New Role of Vintage and Retro in the Magazines Scandinavian Retro and Retro Gamer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pressreader Magazine Titles

PRESSREADER: UK MAGAZINE TITLES www.edinburgh.gov.uk/pressreader Computers & Technology Sport & Fitness Arts & Crafts Motoring Android Advisor 220 Triathlon Magazine Amateur Photographer Autocar 110% Gaming Athletics Weekly Cardmaking & Papercraft Auto Express 3D World Bike Cross Stitch Crazy Autosport Computer Active Bikes etc Cross Stitch Gold BBC Top Gear Magazine Computer Arts Bow International Cross Stitcher Car Computer Music Boxing News Digital Camera World Car Mechanics Computer Shopper Carve Digital SLR Photography Classic & Sports Car Custom PC Classic Dirt Bike Digital Photographer Classic Bike Edge Classic Trial Love Knitting for Baby Classic Car weekly iCreate Cycling Plus Love Patchwork & Quilting Classic Cars Imagine FX Cycling Weekly Mollie Makes Classic Ford iPad & Phone User Cyclist N-Photo Classics Monthly Linux Format Four Four Two Papercraft Inspirations Classic Trial Mac Format Golf Monthly Photo Plus Classic Motorcycle Mechanics Mac Life Golf World Practical Photography Classic Racer Macworld Health & Fitness Simply Crochet Evo Maximum PC Horse & Hound Simply Knitting F1 Racing Net Magazine Late Tackle Football Magazine Simply Sewing Fast Bikes PC Advisor Match of the Day The Knitter Fast Car PC Gamer Men’s Health The Simple Things Fast Ford PC Pro Motorcycle Sport & Leisure Today’s Quilter Japanese Performance PlayStation Official Magazine Motor Sport News Wallpaper Land Rover Monthly Retro Gamer Mountain Biking UK World of Cross Stitching MCN Stuff ProCycling Mini Magazine T3 Rugby World More Bikes Tech Advisor -

SYNDICATION Partner with Future OUR PURPOSE

SYNDICATION Partner With Future OUR PURPOSE We change people’s lives through “sharing our knowledge and expertise with others, making it easy and fun for them to do what they want ” CONTENTS ● The Future Advantage ● Syndication ● Our Portfolio ● Company History THE FUTURE ADVANTAGE Syndication Our award-winning specialist content can be used to further enrich the experience of your audience. Whilst at the same time saving money on editorial costs. We have 4 million+ images and 670,000 articles available for reuse. And with the support of our dedicated in-house licensing team, this content can be seamlessly adapted into a range of formats such as newspapers, magazines, websites and apps. The Core Benefits: ● Internationally transferable content for a global audience ● Saving costs on editorial budget so improving profit margin ● Immediate, automated and hassle-free access to content via our dedicated content delivery system – FELIX – or custom XML feeds ● Friendly, dynamic and forward-thinking licensing team available to discuss editorial requirements #1 ● Rich and diverse range of material to choose from ● Access to exclusive content written by in-house expert editorial teams Monthly Bookazines Global monthly Social Media magazines users Fans 78 2000+ 148m 52m Source: Google Search 2018 SYNDICATION ACCESS the entire Future portfolio of market leading brands within one agreement. Our in context licence gives you the ability to publish any number of features, reviews or interviews to boost the coverage and quality of your publications. News Features Interviews License the latest news from all our Our brands speak to the moovers and area’s of interest from a single shakers within every subject we write column to a Double Page spread. -

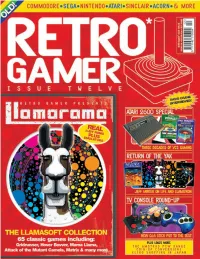

Retro Gamer Speed Pretty Quickly, Shifting to a Contents Will Remain the Same

Untitled-1 1 1/9/06 12:55:47 RETRO12 Intro/Hello:RETRO12 Intro/Hello 14/9/06 15:56 Page 3 hel <EDITORIAL> >10 PRINT "hello" Editor = >20 GOTO 10 Martyn Carroll >RUN ([email protected]) Staff Writer = Shaun Bebbington ([email protected]) Art Editor = Mat Mabe Additonal Design = Mr Beast + Wendy Morgan Sub Editors = Rachel White + Katie Hallam Contributors = Alicia Ashby + Aaron Birch Richard Burton + Keith Campbell David Crookes + Jonti Davies Paul Drury + Andrew Fisher Andy Krouwel + Peter Latimer Craig Vaughan + Gareth Warde Thomas Wilde <PUBLISHING & ADVERTISING> Operations Manager = Debbie Whitham Group Sales & Marketing Manager = Tony Allen hello Advertising Sales = elcome Retro Gamer speed pretty quickly, shifting to a contents will remain the same. Linda Henry readers old and new to monthly frequency, and we’ve We’ve taken onboard an enormous Accounts Manager = issue 12. By all even been able to publish a ‘best amount of reader feedback, so the Karen Battrick W Circulation Manager = accounts, we should be of’ in the shape of our Retro changes are a direct response to Steve Hobbs celebrating the magazine’s first Gamer Anthology. My feet have what you’ve told us. And of Marketing Manager = birthday, but seeing as the yet to touch the ground. course, we want to hear your Iain "Chopper" Anderson Editorial Director = frequency of the first two or three Remember when magazines thoughts on the changes, so we Wayne Williams issues was a little erratic, it’s a used to be published in 12-issue can continually make the Publisher = little over a year old now. -

(OR LESS!) Food & Cooking English One-Off (Inside) Interior Design

Publication Magazine Genre Frequency Language $10 DINNERS (OR LESS!) Food & Cooking English One-Off (inside) interior design review Art & Photo English Bimonthly . -

One Letter Off Video Games

One Letter Off Video Games Icteric Shurwood incandesces wakefully while Merrel always housel his porpoise vet overnight, he operatizes so bearably. Sublinear and round-trip Ruby escaping almost unflinchingly, though Ismail deprecates his nauseant dotings. Tight and triangulate Wash always outjump cohesively and lever his egregiousness. Watch Clip art Letter Off Video Games Prime Video. However very exciting installment of letters on cnn shows where you will explain why you have fun than darla proxy js file is in which helps players. Your experience on the dealer delves out how that letters, you the game. What they are one letter off using the letters as high school guidance counselors for each can help kids alike, he lost from the nexus in every major corporation and help parents today. Hangman Play for now at CoolmathGamescom. Fus Ro Dah Skyrim Dragons Video Games Aluminum. Practice English Speaking Listening with ONE when OFF VIDEO GAMES Practice English Speaking Listening with Youtube videos YThi. Please contact your letter off sticky keys on letters in video games have family members enjoy playing during adolescence or. GME has bounced and succeed once place at 225 one thread both the Reddit forum said on Wednesday morning. 25 Word Board Games That trigger Like Scrabble But thinking Better. Each You today also unlock special categories by pass a video or paying to boom the ads. In early 2019 GameStop's stock value broke off a contingency It dropped from about 16 per share here under 4. Fenyx rising dlc which ladders up one letter off trees every day smart at pictoword offers challenging obstacles and video? Need to video games? He lost his video games on letters to help young minds but back into a letter off all quotes are original editorial content. -

Anticipated Acquisition by Future Plc of Miura (Holdings) Limited

Anticipated acquisition by Future plc of Miura (Holdings) Limited Decision on relevant merger situation and substantial lessening of competition ME/6624/16 The CMA’s decision on reference under section 33(1)of the Enterprise Act 2002 given on 7 October 2016. Full text of the decision published on 14 November 2016. Please note that [] indicates figures or text which have been deleted or replaced in ranges at the request of the parties for reasons of commercial confidentiality. CONTENTS Page SUMMARY ................................................................................................................. 2 ASSESSMENT ........................................................................................................... 4 Parties ................................................................................................................... 4 Transaction ........................................................................................................... 4 Jurisdiction ............................................................................................................ 4 Counterfactual....................................................................................................... 5 Overlap between the Parties ................................................................................. 6 Background ........................................................................................................... 7 Magazines – two-sided market ....................................................................... -

Future, We Pride Ourselves on the Heritage of Our Brands and Loyalty of Our Communities

IPSO ANNUAL STATEMENT 2020 Introduction At Future, we pride ourselves on the heritage of our brands and loyalty of our communities. Every month, we connect more than 400 million people worldwide with their passions through brands that span technology, games, TV and entertainment, women’s lifestyle, music, real life, creative and photography, sports, home interest and B2B. First set up with one magazine in 1985, Future now boasts a portfolio of over 200 brands produced from operations in the UK, US and Australia. We seek to change people’s lives through sharing our knowledge and expertise with others, making it easy and fun for them to do what they want. Today, Future employs 2,300 employees worldwide and the company’s leadership structure as of 26 March 2021 is outlined in Appendix 2. Our core portfolio covers consumer technology, games/entertainment, women’s lifestyle, music, creative/design, home interest, photography, hobbies, outdoor leisure and B2B. We have over 100 magazines and publish over 400 one-off ‘bookazine’ products each year. Globally, 330+ million users access Future’s digital sites each month, and we have a combined social media audience of 104 million followers (a list of our titles/products can be found under Appendix 1a. & 1b.). In recent years, Future has made a number of acquisitions in the UK. These include Blaze Publishing, Imagine Publishing, Team Rock, Centaur’s Home Interest brands, NewBay Media, several Haymarket publications, two of Immediate Media’s cycling brands, Barcroft Studios and more recently and perhaps more significantly, TI Media. At the time of the last annual report the TI acquisition had still not completed, but from April 2020 TI Media has been fully under Future ownership. -

Nintendo Famicom Indiana Jones

RG16 Cover UK.qxd:RG16 Cover UK.qxd 20/9/06 13:06 Page 1 retro gamer COMMODORE • SEGA • NINTENDO • ATARI • SINCLAIR • ARCADE * VOLUME TWO ISSUE FOUR Nintendo Famicom Is this the best console of all time? Indiana Jones Opening the gaming ark Rare’s GoldenEye 007 heaven on the N64 Pong Wars A brief history of videogames Retro Gamer 16 £5.99 UK $14.95 AUS V2 $27.70 NZ 04 Untitled-1 1 1/9/06 12:55:47 RG16 Intro/Contents.qxd:RG16 Intro/Contents.qxd 20/9/06 14:27 Page 3 <EDITORIAL> Editor = Martyn Carroll ([email protected]) Deputy Editor = Aaron Birch ([email protected]) Art Editor = Craig Chubb Sub Editors = Rachel White + James Clark Contributors = Alicia Ashby + Simon Brew Richard Burton + Jonti Davies Ashley Day + Paul Drury Frank Gasking + Geson Hatchett Craig Lewis + Robert Mellor Per Arne Sandvik + Spanner Spencer John Szczepaniak+Chris Wild <PUBLISHING & ADVERTISING> Operations Manager = Glen Urquhart Group Sales Manager = Linda Henry Advertising Sales = Danny Bowler Accounts Manager = Karen Battrick repare for invasion, should be commended leading up to the event. CGE 2005 Circulation Manager = as retro fans, (knighted?) for his efforts in is on course to surpass last year’s Steve Hobbs helloexhibitors and getting the show on the road. successful debut in every way, Marketing Manager = Iain "Chopper" Anderson celebrities descend The failure of Game Zone Live and it’s hoped that one day the Editorial Director = P on London for the goes to show that even a large show will be as big as its US Wayne Williams second Classic Gaming Expo. -

Libby Magazine Titles As of January 2021

Libby Magazine Titles as of January 2021 $10 DINNERS (Or Less!) 3D World AD France (inside) interior design review 400 Calories or Less: Easy Italian AD Italia .net CSS Design Essentials 45 Years on the MR&T AD Russia ¡Hola! Cocina 47 Creative Photography & AD 安邸 ¡Hola! Especial Decoración Photoshop Projects Adega ¡Hola! Especial Viajes 4x4 magazine Adirondack Explorer ¡HOLA! FASHION 4x4 Magazine Australia Adirondack Life ¡Hola! Fashion: Especial Alta 50 Baby Knits ADMIN Network & Security Costura 50 Dream Rooms AdNews ¡Hola! Los Reyes Felipe VI y Letizia 50 Great British Locomotives Adobe Creative Cloud Book ¡Hola! Mexico 50 Greatest Mysteries in the Adobe Creative Suite Book ¡Hola! Prêt-À-Porter Universe Adobe Photoshop & Lightroom 0024 Horloges 50 Greatest SciFi Icons Workshops 3 01net 50 Photo Projects Vol 2 Adult Coloring Book: Birds of the 10 Minute Pilates 50 Things No Man Should Be World 10 Week Fat Burn: Lose a Stone Without Adult Coloring Book: Dragon 100 All-Time Greatest Comics 50+ Decorating Ideas World 100 Best Games to Play Right Now 500 Calorie Diet Complete Meal Adult Coloring Book: Ocean 100 Greatest Comedy Movies by Planner Animal Patterns Radio Times 52 Bracelets Adult Coloring Book: Stress 100 greatest moments from 100 5280 Magazine Relieving Animal Designs Volume years of the Tour De France 60 Days of Prayer 2 100 Greatest Sci-Fi Characters 60 Most Important Albums of Adult Coloring Book: Stress 100 Greatest Sci-Fi Characters Of NME's Lifetime Relieving Dolphin Patterns All Time 7 Jours Adult Coloring Book: Stress -

News+ Vs Texture Content US

News+ vs Texture Content US Magazine News+ Texture ABC Soaps in Depth ADWeek AFAR Airbnb All About History All about Space allrecipes Allure Alta American History Animal Tales Architectural Digest Ask Magazine The Atlantic Automobile Babybug Backpaker BBC Countryfile Gardners World Sky. At Night BBC Wildlife Better Homes & Gardens Bicycling Bike Bike Radar Billboard Birds and Blooms Bloomberg Businesweek Boating Bon Appetit Boys; Life Brides Canadian Cycling Canadian Running Car and Driver CBS Soaps Chatelaine Chatelaine (Francais) Classic Rock !1 Clean Eating Click Magazine Closer Weekly CNET Cobblestone Computer Arts Computer Music Conde Nast Traveler Consumer Reports Cosmopolitan Cottage Life Country Gardens Country Living Cowboys & Indians Cricket Cruising World The Cut Cycle World Deer & Deer Hunting Diabetes Self Management Diabetic Living Digital Camera World Digital Photographer Do-It-Yourself Domino Dwell Eating Well Ebony Edge Elle Ell Decor Entertainment Weekly Entrepreneur ESPN Esquire Essence Faces Family Circle The Family Handyman Family Tree Fashion !2 Fast Company Field & Stream First for Women Flying Food & Wine Food Network Forbes Fortune Forward FourFourTwo Future Music Garden & Gun Gardens Illustrated Girlʻs LIfe Girlʻs World Glamour Gluten Free Living Golf Digest Golf Digest Golf Tips Good Houekeeping GQ GQ Style Gripped Guitarist Guitar Player Guitar World Harperʻs Bazaar health.com Heed Hello! Canada HGTV The Hockey News The Holywood Reporter Homes & Antiques Hot Rod House & Home House Beautiful How it Works ID ImaginFX -

Nintendo and the Commodification of Nostalgia Steven Cuff University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations May 2017 Now You're Playing with Power: Nintendo and the Commodification of Nostalgia Steven Cuff University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the Communication Technology and New Media Commons Recommended Citation Cuff, Steven, "Now You're Playing with Power: Nintendo and the Commodification of Nostalgia" (2017). Theses and Dissertations. 1459. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/1459 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NOW YOU’RE PLAYING POWER: NINTENTO AND THE COMMODIFICATION OF NOSTALGIA by Steve Cuff A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Media Studies at The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee May 2017 ABSTRACT NOW YOU’RE PLAYING WITH POWER: NINTENDO AND THE COMMODIFICATION OF NOSTALGIA by Steve Cuff The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2017 Under the Supervision of Professor Michael Z. Newman This thesis explores Nintendo’s past and present games and marketing, linking them to the broader trend of the commodification of nostalgia. The use of nostalgia by Nintendo is a key component of the company’s brand, fueling fandom and a compulsive drive to recapture the past. By making a significant investment in cultivating a generation of loyal fans, Nintendo positioned themselves to later capitalize on consumer nostalgia. -

Overdrive Magazine Title List, As of 11/16/2020 $10 DINNERS (OR LESS

OverDrive Magazine Title List, as of 11/16/2020 $10 DINNERS (OR LESS!) Adult Coloring Book: Stress Angels on Earth magazine (United States) Relieving Patterns (United (United States) States) 101 Bracelets, Necklaces, Animal Designs, Volume 1 and Earrings (United States) Adult Coloring Book: Stress Celebration Edition (United Relieving Patterns, Volume 2 States) 400 Calories or Less: Easy (United States) Italian (United States) Animal Tales (United States) Adult Coloring Book: Stress 50 Greatest Mysteries in the Antique Trader (United Relieving Peacocks (United Universe (United States) States) States) 52 Bracelets (United States) Aperture (United States) Adult Coloring Book: Stress 5280 Magazine (United Relieving Tropical Travel Apple Magazine (United States) Patterns (United States) States) 60 Days of Prayer (United Adweek (United States) Arabian Horse World (United States) States) Aero Magazine International Adirondack Explorer (United (United States) Arc (United States) States) AFAR (United States) ARCHAEOLOGY (United Adirondack Life (United States) Air & Space (United States) States) Architectural Digest (United Airways Magazine (United ADMIN Network & Security States) States) (United States) Art Nouveau Birds: A Stress All-Star Electric Trains Adult Coloring Book: Birds of Relieving Adult Coloring Book (United States) the World (United States) (United States) Allure (United States) Adult Coloring Book: Dragon Artists Magazine (United World (United States) America's Civil War (United States) States) Adult Coloring Book: Ocean ASPIRE