Best Cultural Heritage Stewardship Practices by and for the White

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fixing Historic Preservation: a Constructive Critique of “Significance”

Peer Reviewed Title: Fixing Historic Preservation: A Constructive Critique of "Significance" [Research and Debate] Journal Issue: Places, 16(1) Author: Mason, Randall Publication Date: 2004 Publication Info: Places Permalink: http://escholarship.org/uc/item/74q0j4j2 Acknowledgements: This article was originally produced in Places Journal. To subscribe, visit www.places-journal.org. For reprint information, contact [email protected]. Keywords: places, placemaking, architecture, environment, landscape, urban design, public realm, planning, design, research, debate, historic, preservation, contructive, critique, significance, Randall Mason Copyright Information: All rights reserved unless otherwise indicated. Contact the author or original publisher for any necessary permissions. eScholarship is not the copyright owner for deposited works. Learn more at http://www.escholarship.org/help_copyright.html#reuse eScholarship provides open access, scholarly publishing services to the University of California and delivers a dynamic research platform to scholars worldwide. Fixing Historic Preservation: A Constructive Critique of “Significance” Randall Mason The idea of “significance” is exceed- Second, once judgments are made projects that tell their particular sto- ingly important to the practice of about a site, its significance is regarded ries. The broadening of preservation historic preservation. In significance, as largely fixed. Such inertia needs to from its curatorial roots has been a preservationists pack all their theory, be overcome, and -

1. Introduction

This PDF is a simplified version of the original article published in Internet Archaeology. All links also go to the online version. Please cite this as: Nicholson, C., Fernandez, R. and Irwin, J. 2021 Digital Archaeological Data in the Wild West: the challenge of practising responsible digital data archiving and access in the United States, Internet Archaeology 58. https://doi.org/10.11141/ia.58.22 Digital Archaeological Data in the Wild West: the challenge of practising responsible digital data archiving and access in the United States Christopher Nicholson, Rachel Fernandez and Jessica Irwin Summary Archaeology in the United States is conducted by a number of different sorts of entities under a variety of legal mandates that lack uniform standards for data archiving. The difficulty of accessing data from projects in which one was not directly involved indicates an apparent reluctance to archive raw data and supplemental information with digital repositories to be reused in the future. There is hope that additional legislation, guidelines from professional organisations, and educational efforts will change these practices. 1. Introduction Though we are well into the 21st century, responsible digital archiving of archaeological data in the United States is not common practice. Digital archiving of cultural resource management reports in State Historic Preservation Offices, where they are often available by request though perhaps at a cost, is common; however, digitally archiving the datasets and other supporting materials that went into the creation of those documents is not. Though a vocal minority advocates for responsible digital archiving practices (Kansa and Kansa 2013; 2018; Kansa et al. -

Federal Laws and Regulations Requiring Curation of Digital Archaeological Documents and Data

Federal Laws and Regulations Requiring Curation of Digital Archaeological Documents and Data Cultural Heritage Partners, PLLC Prepared for: Arizona State University October 25th, 2012 © 2012 Arizona State University. All rights reserved. This report by Cultural Heritage Partners, PLLC describes and analyzes federal requirements for the access to and long-term preservation of digital archaeological data. We conclude that the relevant federal laws, regulations, and policies mandate that digital archaeological data generated by federal agencies must be deposited in an appropriate repository with the capability of providing appropriate long-term digital curation and accessibility to qualified users. Federal Agency Responsibilities for Preservation and Access to Archaeological Records in Digital Form Federal requirements for appropriate management of archaeological data are set forth in the National Historic Preservation Act (“NHPA”), the Archaeological Resources Protection Act (“ARPA”), the regulations regarding curation of data promulgated pursuant to those statutes (36 C.F.R. 79), and the regulations promulgated by the National Archives and Records Administration (36 C.F.R. 1220.1-1220.20) that apply to all federal agencies. We discuss each of these authorities in turn. Statutory Authority: Maintenance of Archaeological Data Archaeological data can be generated from many sources, including investigations or studies undertaken for compliance with the NHPA, ARPA, and other environmental protection laws. The NHPA was adopted in 1966, and strongly -

DIGITAL DOCUMENTATION for HISTORIC RESOURCES By

DIGITAL DOCUMENTATION FOR HISTORIC RESOURCES by MELISSA EVE GOGO Under the Direction of Mark Reinberger ABSTRACT This paper briefly analyzes the current documentation standards for Federal programs and creates an argument for the use of digital technologies in historic documentation. The technologies of photogrammetry, and laser scanning are addressed as methods for three dimensional modeling and compared to the current standard. Additionally, the issues posed by archiving on digital media are presented and courses of action suggested. Finally, the feasibility of a universal file format for archival purposes is addressed, and current progression toward this goal discussed. INDEX WORDS: Historic resource documentation, Photogrammetry, Laser scanning, Digital photography, HABS documentation guidelines, Digital storage media, Universal file format DIGITAL DOCUMENTATION FOR HISTORIC RESOURCES by MELISSA EVE GOGO B.S., State University of New York at New Paltz, 2005 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF HISTORIC PRESERVATION ATHENS, GEORGIA 2011 © 2011 Melissa Eve Gogo All Rights Reserved DIGITAL DOCUMENTATION FOR HISTORIC RESOURCES by MELISSA EVE GOGO Major Professor: Mark Reinberger Committee: Wayde Brown Ashley Calabria Christine Perkins Electronic Version Approved: Maureen Grasso Dean of the Graduate School The University of Georgia May 2011 iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to acknowledge my major professor, Mark Reinberger, for agreeing -

Historic Preservation

Historic Preservation Request We urge Congress to: • support FY 2021 funding of $61 million for State Historic Preservation Offices (SHPOs) and $22 million for Tribal Historic Preservation Offices (THPOs). • provide $18 million for Save America's Treasures. • provide $28 million for competitive grants to preserve the sites and stories of the Civil Rights Movement. • support $10 million for Paul Bruhn Historic Revitalization grants for the rehabilitation of historic properties and economic development of rural communities. • continue to support the Historic Tax Credit by cosponsoring the Historic Tax Credit Growth and Opportunity Act (H.R. 2825/S. 2615). • support the legislative proposals recommended by the U.S. Semiquincentennial Commission in its report to the President on the country’s 250th commemoration. Introduction State Historic Preservation Offices (SHPOs) and Tribal Historic Preservation Offices (THPOs) carry out the work of the federal government in the states and tribal communities: finding America’s historic places, making nominations to the National Register of Historic Places, reviewing impacts of federal projects, providing assistance to developers seeking a rehabilitation tax credit, creating alliances with local government preservation commissions and conducting preservation education and planning. This federal-state-local foundation of America’s historic preservation program was established by the National Historic Preservation Act. Established in 1998, Save America's Treasures is a public-private partnership that includes the National Park Service, the Institute of Museum and Library Services, and other federal cultural agencies. The grant program helps preserve nationally significant historic properties and collections that convey our nation's rich heritage to future generations of Americans. Since 1999, there have been almost 4,000 requests for funding totaling $1.54 billion. -

Cultural Resource Management U.S. National Park Service Presented To

Cultural Resource Management U.S. National Park Service Presented to The Institute for Parks, People and Biodiversity University of California September 6, 2019 Stephanie Toothman, Ph.D. Kalaupapa National Historical Park Cultural Resource Management The National Park Service will protect, preserve, and foster appreciation of the cultural resources in its custody and demonstrate its respect for the peoples traditionally associated with Big Hole National Battlefield those resources through appropriate programs of research, planning, and stewardship. National Park Service Management Policies 2006, Cultural Resource Management, Chapter Five. Cultural Resources: Tangible and intangible aspects of cultural systems, both living and dead, that are valued by or representative of a given culture or that contain information about a culture. Effigy Mounds National Monument Independence National Historical Park Culture/Nature: Natural resources such as fish, clean water, and plant materials may be considered as cultural resources if they support a way of life. Salmon returning to the Elwha River, Olympic National Park Musselshell Meadows, Nez Perce National Historical Park NPS Cultural Resources Classifications • Archeological Resources • Cultural Landscapes • Ethnographic Resources • Historic and Prehistoric Structures • Museum Collections Fort Monroe National Monument Archeological Resources are the sites and material remains of past human life or activities which are of archeological interest such as tools, pottery, rock carvings, and human remains. Knife River Indian Villages National Historic Site Jamestown, Colonial National Historical Park Biscayne National Park Petrified Forest National Park Cultural Landscapes represent the combined works of nature and man. They are geographic areas, including both cultural and natural resources associated with a historic event, activity, or person or exhibiting other cultural or aesthetic values. -

Cultural Resources Update

Cultural Resources Update Department of Defense Cultural Resources Program Newsletter Volume 11, No 1, Spring/Summer 2015 The NHPA’s New Home in the US Code—Title 54 By Michelle Volkema with contributions from John Renaud, NPS As you’ve probably already heard, the National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA) has a new home in the United States Code. The NHPA’s previous home was in Title 16 – Conservation, 16 U.S.C. § 470 et seq. Its new location is Title 54 – National Park Service and Related Programs, 54 U.S.C. § 300101 et seq. While the name “National Historic Preservation Act” has been removed from Title 54, the NHPA remains a valid statute of law, P.L. 89-665. As such, referring to sections of the NHPA as “Section 106” or “Section 110” is still correct, as those are sections of the statute and not the code, however their legal citations have changed. While the code revision was a surprise to many, it is actually just another step in a long effort to clean up the U.S. Code undertaken by the Office of the Law Revision Counsel (OLRC) beginning in 1974. The OLRC is an office within the US House of Representatives, and is tasked with maintaining, revising, and updating the U.S. Code. More about the OLRC here: http:// uscode.house.gov/about_office.xhtml;jsessionid=DC0095D711738160D197FBB4B0466803 Signed in 1974, Public Law 93-554 (2 U.S.C. 285b(1)) directed the OLRC to begin cleaning up the U.S. Code, including revision and reorganization. So, in December 2014, when President Obama signed P.L. -

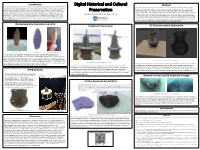

Digital Cultural and Historical Preservation Is Important for Keeping an Archive of Artifacts Replicas That Can Be Used for Accurate Measuring (Richardson Et Al

Introduction Digital Historical and Cultural Abstract It is now possible to digitally preserve and share artifacts and historical sites through the internet with the use The intent of this research is to test the effectiveness of different 3D model-making methods for digital of digital preservation techniques (Vincent et al 2017). Archaeologists and researchers can more easily collect, historical and cultural preservation. The case studies presented are of two historic pots, a lithic, a bitumen analyze, and disseminate information with the use of photogrammetry software and 3D scanning (Porter, sample, a shipwreck, and an historic windmill. The 3D models were created with the photogrammetry Roussel, & Soressi 2016). With the availability of this newer technology and the creation of 3D models, the Preservation software Agisoft Metashape and the 3D mapping Structure Sensor Mark II. Equipment used in this research public’s cultural heritage has become more assessable (McCarthy & Benjamin, J. 2014). The techniques included a DSLR camera, tripod, photo box, lazy Susan, a scale for the small objects, and a drone for the discussed in this research provide an opportunity to go beyond photographic recording and create virtual Natalie Heacock, Mark Schwartz, Ph. D. windmill project. Digital cultural and historical preservation is important for keeping an archive of artifacts replicas that can be used for accurate measuring (Richardson et al. 2012) and even printing for education and heritage sites, not only for the sake of analysis, education, and public availability, but in case of damage purposes (Pollalis et al. 2018). This exciting newer technology opens many doors for archaeologists and or loss to the sites in the future. -

Cultural Resources Management Element

CULTURAL RESOURCES MANAGEMENT ELEMENT Cultural Resources Management No city can hope to understand its present or to forecast its future if it fails to recognize its past. For by tracing the past, a city can gain a clear sense of the process by which it achieved its present form and substance; and, even more importantly, how it is likely to continue to evolve. For these reasons, efforts directed to identifying and preserving San Diego's historic and archaeological resources - with their inherent ability to evoke the past - are most advisably pursued. Cultural resources are physical features, both natural and man-made, associated with human activity. These may include such physical objects and features as archaeological sites and artifacts, buildings, groups of buildings, street furniture, signs, and planted materials; in short, almost anything that connotes man's past presence. For purposes of this element, a distinction is made between "archaeological" and "historic" sites. This distinction is based on the authoritative work of the State Archeological, Paleontological and Historical Task Force, appointed by former Governor Ronald Reagan in 1971, whose work culminated in the publication “The Status of California's Heritage: A report to the Governor and Legislature of California,” by W.R. Green, et. al., September 1, 1973. The California Task Force used the term "archeological site" to mean any mound, midden, burial ground, mine, trail, rock art, or other location containing evidence of human activities which took place before 1750 A.D. An "historic site" is any structure, place, or feature which is or may be significant in the state's past (1542 A.D.) history, architecture, or culture. -

Chapter 18: Lead-Based Paint and Historic Preservation

Chapter 18: Lead-Based Paint and Historic Preservation HOW TO DO IT ............................................................................................................................. 18–3 I. Introduction ............................................................................................................................. 18–6 II. Use of Lead-Based Paint in Historic Properties ................................................................... 18–6 III. Standards for the Treatment of Historic Properties ............................................................. 18–6 IV. Property Evaluation ................................................................................................................ 18–8 A. Evaluating the Significance of a Property ....................................................................... 18–8 B. Risk Assessment/Paint Inspection ................................................................................. 18–10 V. Establishing Priorities for Intervention ................................................................................ 18–10 VI. Selecting Interim Controls or Abatement ........................................................................... 18–10 VII. Selecting Abatement Methods Other Than Paint Stabilization ........................................ 18–11 A. Paint Removal ................................................................................................................... 18–11 B. Component Removal and Replacement ....................................................................... -

Addressing an Historic Preservation Dilemma: the Future of Nineteenth-Century Farmstead Archaeology in the Northeast Terry H

Northeast Historical Archaeology Volume 31 Special Issue: Historic Preservation and the Archaeology of Nineteenth-Century Farmsteads in the Article 13 Northeast 2001 Addressing an Historic Preservation Dilemma: The Future of Nineteenth-Century Farmstead Archaeology in the Northeast Terry H. Klein Sherene Baugher Follow this and additional works at: http://orb.binghamton.edu/neha Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Klein, Terry H. and Baugher, Sherene (2001) "Addressing an Historic Preservation Dilemma: The uturF e of Nineteenth-Century Farmstead Archaeology in the Northeast," Northeast Historical Archaeology: Vol. 30-31 31, Article 13. https://doi.org/10.22191/neha/vol31/iss1/13 Available at: http://orb.binghamton.edu/neha/vol31/iss1/13 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB). It has been accepted for inclusion in Northeast Historical Archaeology by an authorized editor of The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB). For more information, please contact [email protected]. Addressing an Historic Preservation Dilemma: The uturF e of Nineteenth- Century Farmstead Archaeology in the Northeast Cover Page Footnote We thank Mary Beaudry, Lu Ann De Cunzo, George Miller, Richard eit, and Lou Ann Wurst for their insightful comments on earlier drafts of this summary. We also thank David Landon and Ann-Eliza Lewis for their editorial suggestions, and Dena Doroszenko for taking the time to update us on how site evaluations are made in Ontario, Canada. Finally, we thank Lynne Sebastian for reminding us about William Lipe's timeless and seminal article "A Conservation Model for American Archaeology." It was amazing to see that Lipe's recommendations still serve as a guide for addressing current historic preservation issues. -

Tania Alam Historic Preservation, Graduate School of Architecture, Planning & Preservation, Columbia University

Tania Alam Historic Preservation, Graduate School of Architecture, Planning & Preservation, Columbia University. Supervisor: Mary Jablonski The Evolution of “American Historic Color Palettes” ` Alam, ANAGPIC 2017, 2 Abstract ―Historic Color Palette‖ is a group of paint colors placed together that are supposed to have a historic connection to architecture. This paper takes a look at how these color palettes came into existence and how they have developed over time. The concept of linking certain color groups to particular time-periods and places is an intriguing one. It first emerged in the United States as a descriptor of historic colors discovered at Colonial Williamsburg. With time the palettes have extended beyond Colonial period and even the midcentury modern. These palettes have grown over time to become a popular means of creating visual connections to the past. But what do these colors represent? The thesis was initially undertaken to explore where ―historic color palettes‖ came from and to examine the evolution of the special color collections that form the American ―Historic Color Palettes.‖ Representing specific regions and time-periods in history, the ―historic color palette‖ is an important means of telling the story of the nation. For this research, a number of ―historic color palettes‖ were selected as case-studies. These were not limited to palettes being produced commercially, and also included lesser-known palettes, which have made significant contributions to the development of respective areas. The research process entailed the study of historic paint brochures and early paint advertisements, along with archival research and interviews with people working in the development of the historic palettes.