Malou, Hindi Pa Ako Tapos

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DEPARTMENT of EDUCATION REGION XII City of Koronadal, Philippines Telefax No

REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION REGION XII City of Koronadal, Philippines Telefax No. (083) 228-8825; email: [email protected] Website: depedroxii.org January 16, 2018 REGION MEMORANDUM No.01 s. 2018 1st REGIONAL INTEGRATED AWARDING CEREMONY TO: Schools Division Superintendents Asst. Schools Division Superintendents All Other Concerned Personnel 1. To recognize exemplary performances of schools in terms of partnership, provision of inclusive education and child-centered community education, the Department of Education-Region XII shall hold an “Integrated Regional Gawad Parangal” on January 24, 2018 – 10:00AM at the Convention Center of The Farm @ Carpenter Hill, Koronadal City. 2. Working on the theme, “Transcending Barriers Toward Inclusive Education,” the activity aims to give due recognition to school heads, program focal persons and stakeholders for their exemplary performance in implementing the different DepEd Programs and Projects for SY 2017-2018 such as: a) Brigada Eskwela Best Implementing Schools, b) School-Based Feeding Program Outstanding Implementers, c) Barkada Kontra Droga Best Implementers, d) Gawad Siklab Best Implementers, and e) 2015 PBB Outstanding Performance. 3. Awardees by category shall receive the following: Programs and Projects Rank Awards to be received Brigada Eskwela Best 1st, 2nd and 3rd placers Plaques/Trophies of Implementing Schools Recognition Finalists Certificates of Recognition School-Based Feeding 1st, 2nd 3rd placers Plaques of Recognition, Program Outstanding Certificates -

II III IVIV VV Davao Davao 0 75 150 Km II II III

Earthquake Green Shaking Alert M 6.3, MINDANAO, PHILIPPINES Origin Time: Mon 2014-07-14 07:59:57 UTC (15:59:57 local) PAGER o o Location: 5.71 N 126.48 E Depth: 20 km Version 4 Created: 6 weeks, 2 days after earthquake Estimated Fatalities Green alert for shaking-related fatalities Estimated Economic Losses 99% and economic losses. There is a low 99% likelihood of casualties and damage. 1% 1% 1 100 10,000 1 100 10,000 10 1,000 100,000 10 1,000 100,000 Fatalities USD (Millions) Estimated Population Exposed to Earthquake Shaking ESTIMATED POPULATION - -* 17,501k 620k 0 0 0 0 0 0 EXPOSURE (k = x1000) ESTIMATED MODIFIED MERCALLI INTENSITY PERCEIVED SHAKING Not felt Weak Light Moderate Strong Very Strong Severe Violent Extreme Resistant none none none V. Light Light Moderate Moderate/Heavy Heavy V. Heavy POTENTIAL Structures DAMAGE Vulnerable Structures none none none Light Moderate Moderate/Heavy Heavy V. Heavy V. Heavy *Estimated exposure only includes population within the map area. Population Exposure population per ~1 sq. km from Landscan Structures: Overall, the population in this region resides in structures that are a mix of vulnerable and 124°E 126°E 128°E II earthquake resistant construction. Historical Earthquakes (with MMI levels): Date Dist. Mag. Max Shaking ButigButig ButigButig WaoWao DonDon CarlosCarlos CompostelaCompostela ImeldaImeldaImelda WaoWao DonDon CarlosCarlos CompostelaCompostela (UTC) (km) MMI(#) Deaths NewNew CorellaCorella BagangaBaganga BayangaBayanga NewNew CorellaCorella BagangaBaganga BayangaBayanga DamulogDamulog -

Chapter 5 Existing Conditions of Flood and Disaster Management in Bangsamoro

Comprehensive capacity development project for the Bangsamoro Final Report Chapter 5. Existing Conditions of Flood and Disaster Management in Bangsamoro CHAPTER 5 EXISTING CONDITIONS OF FLOOD AND DISASTER MANAGEMENT IN BANGSAMORO 5.1 Floods and Other Disasters in Bangsamoro 5.1.1 Floods (1) Disaster reports of OCD-ARMM The Office of Civil Defense (OCD)-ARMM prepares disaster reports for every disaster event, and submits them to the OCD Central Office. However, historic statistic data have not been compiled yet as only in 2013 the report template was drafted by the OCD Central Office. OCD-ARMM started to prepare disaster reports of the main land provinces in 2014, following the draft template. Its satellite office in Zamboanga prepares disaster reports of the island provinces and submits them directly to the Central Office. Table 5.1 is a summary of the disaster reports for three flood events in 2014. Unfortunately, there is no disaster event record of the island provinces in the reports for the reason mentioned above. According to staff of OCD-ARMM, main disasters in the Region are flood and landslide, and the two mainland provinces, Maguindanao and Lanao Del Sur are more susceptible to disasters than the three island provinces, Sulu, Balisan and Tawi-Tawi. Table 5.1 Summary of Disaster Reports of OCD-ARMM for Three Flood Events Affected Damage to houses Agricultural Disaster Event Affected Municipalities Casualties Note people and infrastructures loss Mamasapano, Datu Salibo, Shariff Saydona1, Datu Piang1, Sultan sa State of Calamity was Flood in Barongis, Rajah Buayan1, Datu Abdulah PHP 43 million 32,001 declared for Maguindanao Sangki, Mother Kabuntalan, Northern 1 dead, 8,303 ha affected. -

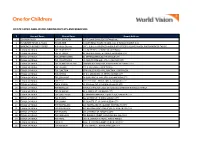

Petron Stations As of 21 July 2020 for Diesel

List of Liquid Fuel Retail Stations or LPG Dealers Implementing the 10% Tariff (EO 113) Company: PETRON Report as of: July 21, 2020 Diesel Estimated No. Station Name Location Implementation Tariff Dates 1 GAMBOA WILLIE MC ARTHUR HIGHWAY VILLASIS, PANGASINAN 20/06/2020 P 1.60/liter 2 NACINO SAMUEL SR. NATIONAL HIGHWAY, GARDEN ARTECHE, EASTERN SAMAR 20/06/2020 P 1.60/liter 3 ROBLES CARMEL C NATIONAL HIGHWAY, POBLACION GAAS BA LEYTE 20/06/2020 P 1.60/liter 4 101 VENTURES SUPPORT CORPORATI OSMENA HIGHWAY COR. CALHOUN ST. MAKATI CITY, METRO MANILA 21/06/2020 P 1.60/liter 5 6PILLARS CORPORATION NATIONAL ROAD BRGY LIDONG STO. DOMINGO ALBAY 21/06/2020 P 1.60/liter 6 8EJJJE TRADING CORP. N DOMINGO COR M PATERNO ST CORAZON DE JESUS, SAN JUAN CITY 21/06/2020 P 1.60/liter 7 8EJJJE TRADING CORP. #47 VALENZUELA COR. F. BLUMENTRITT SAN JUAN CITY, METRO MANI 21/06/2020 P 1.60/liter 8 A8 GAS STATION CORPORATION DULONG NORTE 1 MALASIQUI PANGASINAN 21/06/2020 P 1.60/liter 9 AACAHULOGAN CORPORATION FR MASTERSON AVE. XAVIER STATES CAGAYAN DE ORO CITY, MISAMIS 21/06/2020 P 1.60/liter 10 ABENES GERARDO DELA CRUZ NATIONAL ROAD CORNER METROGATE 2, B MEYCAUAYAN, BULACAN 21/06/2020 P 1.60/liter 11 ABINAL SABI T. III 1 UNANG HAKBANG ST. COR. BAYANI ST. QUEZON CITY 21/06/2020 P 1.60/liter 12 ABREGANA GINY DIOLATA NATIONAL HIGHWAY CAMP1 MARAMAG BUKIDNON 21/06/2020 P 1.60/liter 13 ABUEG FRANCESCA P NATIONAL HIGHWAY PUERTO PRINCESA CITY, PALAWAN 21/06/2020 P 1.60/liter 14 ACAIN FREDIELYN MARTIN LABRADOR - SUAL ROAD LABRADOR, PANGASINAN 21/06/2020 P 1.60/liter 15 ACEDILLO FRITZ GERALD J PUROK SUBIDA PAGADIAN CITY, ZAMBOANGA 21/06/2020 P 1.60/liter 16 ACLER GAS STATION INC COR. -

Determining Staffing Levels for Primary Care Services Using

FINAL REPORT | DECEMBER 19, 2019 Determining Staffing Levels for Primary Care Services using Workload Indicator of Staffing Need in Selected Regions of the Philippines USAID HRH2030/Philippines: Human Resources for Health in 2030 in the Philippines Cooperative Agreement No. AID-OAA-A-15-00046 Cover photo: Mollent Okech, WISN Consultant (third from left), conducting training with the Department of Health in October 2018 (Credit: USAIDHRH2030/Philippines) December 19, 2019 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by members of the HRH2030 consortium. DISCLAIMER This material is made possible by the generous support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) under the terms of cooperative agreement no. AID-OAA-A-15-00046 (2015- 2020). The contents are the responsibility of HRH2030 consortium and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. Determining Staffing Levels for Primary Care Services Using Workload Indicators of Staffing Need in Selected Regions of the Philippines | 2 Contents Acronyms and Abbreviations 6 Definitions of Key Terms 7 Foreword 9 Acknowledgements 10 Executive Summary 11 Background 14 General Objective of the Study 15 Specific Objectives of the Study 15 Study Questions 15 WISN Study Implementation Process in the Philippines 16 Study Design 16 Study Scope 16 Sampling Design, Size and Procedure 16 Study Organization 17 Overview of the WISN Methodology 18 Data Collection, -

List of Ecpay Cash-In Or Loading Outlets and Branches

LIST OF ECPAY CASH-IN OR LOADING OUTLETS AND BRANCHES # Account Name Branch Name Branch Address 1 ECPAY-IBM PLAZA ECPAY- IBM PLAZA 11TH FLOOR IBM PLAZA EASTWOOD QC 2 TRAVELTIME TRAVEL & TOURS TRAVELTIME #812 EMERALD TOWER JP RIZAL COR. P.TUAZON PROJECT 4 QC 3 ABONIFACIO BUSINESS CENTER A Bonifacio Stopover LOT 1-BLK 61 A. BONIFACIO AVENUE AFP OFFICERS VILLAGE PHASE4, FORT BONIFACIO TAGUIG 4 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_HEAD OFFICE 170 SALCEDO ST. LEGASPI VILLAGE MAKATI 5 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_BF HOMES 43 PRESIDENTS AVE. BF HOMES, PARANAQUE CITY 6 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_BETTER LIVING 82 BETTERLIVING SUBD.PARANAQUE CITY 7 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_COUNTRYSIDE 19 COUNTRYSIDE AVE., STA. LUCIA PASIG CITY 8 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_GUADALUPE NUEVO TANHOCK BUILDING COR. EDSA GUADALUPE MAKATI CITY 9 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_HERRAN 111 P. GIL STREET, PACO MANILA 10 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_JUNCTION STAR VALLEY PLAZA MALL JUNCTION, CAINTA RIZAL 11 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_RETIRO 27 N.S. AMORANTO ST. RETIRO QUEZON CITY 12 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_SUMULONG 24 SUMULONG HI-WAY, STO. NINO MARIKINA CITY 13 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP 10TH 245- B 1TH AVE. BRGY.6 ZONE 6, CALOOCAN CITY 14 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP B. BARRIO 35 MALOLOS AVE, B. BARRIO CALOOCAN CITY 15 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP BUSTILLOS TIWALA SA PADALA L2522- 28 ROAD 216, EARNSHAW BUSTILLOS MANILA 16 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP CALOOCAN 43 A. MABINI ST. CALOOCAN CITY 17 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP CONCEPCION 19 BAYAN-BAYANAN AVE. CONCEPCION, MARIKINA CITY 18 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP JP RIZAL 529 OLYMPIA ST. JP RIZAL QUEZON CITY 19 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP LALOMA 67 CALAVITE ST. -

City of Tacurong Was Once a Barangay of the Municipality of Buluan of the Then Empire Province of Cotabato

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND The place, which later became the city of Tacurong was once a barangay of the municipality of Buluan of the then empire province of Cotabato. The place was originally called “Pamasang”, after a creek that flows from south to north of the area. In the 1940s, the place became the way station of the 19-C Survey Team due to is strategic location and suitability for the purposes of the survey team. During those years, the place also became a stopover point for travelers and the Oblate missionaries on their way to the different points of Cotabato Province. The name “Pamasang” was changed to “Talakudong”, the maguindanao term for head covering which was worn by most of the early settlers and people in the area. How the place came to be associated with head covering cannot be ascertained. Eventually, the name was later shortened / changed to Tacurong. It can only be deduced that the present name Tacurong must have originated from the word “Talakudong”. Tacurong was separated from its mother town of Buluan and was created a municipality by Executive Order Number 462 signed by the late President Elpidio Quirino on August 3, 1951. The city is composed of mostly Ilonggo settlers from the province of Iloilo. Tacurong then had an estimated area of 40,000 hectares comprising 14 barangays. When Tantangan, a barangay of Tacurong was created into a municipality in 1961, the southern portions of Tacurong were separated. The area was further reduced when Pres. Quirino was created into a municipality on Nov. 22, 1973 taking with it some of the eastern portions. -

III IVIV Davao Davao 0 75 150 Km

Earthquake Green Shaking Alert M 6.3, MINDANAO, PHILIPPINES Origin Time: Fri 2016-09-23 22:53:10 UTC (22:53:10 local) PAGER o o Location: 6.57 N 126.49 E Depth: 65 km Version 7 Created: 5 weeks, 6 days after earthquake Estimated Fatalities Green alert for shaking-related fatalities Estimated Economic Losses and economic losses. There is a low likelihood of casualties and damage. 65% 65% 30% 30% 4% 4% 1 100 10,000 1 100 10,000 10 1,000 100,000 10 1,000 100,000 Fatalities USD (Millions) Estimated Population Exposed to Earthquake Shaking ESTIMATED POPULATION - -* 13,060k 7,249k 99k 0 0 0 0 0 EXPOSURE (k = x1000) ESTIMATED MODIFIED MERCALLI INTENSITY PERCEIVED SHAKING Not felt Weak Light Moderate Strong Very Strong Severe Violent Extreme Resistant none none none V. Light Light Moderate Moderate/Heavy Heavy V. Heavy POTENTIAL Structures DAMAGE Vulnerable Structures none none none Light Moderate Moderate/Heavy Heavy V. Heavy V. Heavy *Estimated exposure only includes population within the map area. Population Exposure population per ~1 sq. km from Landscan Structures: Overall, the population in this region resides in structures that are a mix of vulnerable and 124°E 126°E 128°E earthquake resistant construction. Historical Earthquakes (with MMI levels): Date Dist. Mag. Max Shaking OroquietaOroquieta InitaoInitaoInitao CagayanCagayan dede OroOro (UTC) (km) MMI(#) Deaths OroquietaOroquieta InitaoInitaoInitao CagayanCagayan dede OroOroTagbinaTagbinaTagbina ManticaoManticao JimenezJimenezJimenez HinatuanHinatuan 1999-05-18 312 5.9 V(75k) 0 IliganIliganIligan -

Professional Regulation Commission Cagayan De Oro Chemical Technician October 10, 2019

PROFESSIONAL REGULATION COMMISSION CAGAYAN DE ORO CHEMICAL TECHNICIAN OCTOBER 10, 2019 School : EAST CITY CENTRAL SCHOOL Address : LAPASAN, CAGAYAN DE ORO CITY Building : MULTI-PURPOSE HALL Floor : 4TH Room/Grp No. : 1 Seat Last Name First Name Middle Name School Attended No. 1 ABA-A FLORIAN TRUZA MINDANAO STATE UNIVERSITY-MARAWI CITY 2 ABAD MA. ERIKA USMAN XAVIER UNIVERSITY 3 ABADEJOS JULIUS DAGANGON BUKIDNON STATE UNIVERSITY(FOR.BUKIDNON STATE COLLEGE)-MAIN CAMPUS 4 ABAO JERSE HILL BERBON CARAGA STATE UNIVERSITY-BUTUAN CITY 5 ABBAS AZIZAH ALIM MINDANAO STATE UNIVERSITY-MARAWI CITY 6 ABELLA HYACINTH JUVEL EASTERN VISAYAS STATE UNIVERSITY (for.LIT)TACLOBAN 7 ABUNDA DAISY LABISTO BUKIDNON STATE UNIVERSITY(FOR.BUKIDNON STATE COLLEGE)-MAIN CAMPUS 8 ACAS MEG INA SIENES MINDANAO STATE UNIVERSITY-ILIGAN INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY 9 AFAN JEZANIAH DARYLLE JAMOLES NOTRE DAME OF MARBEL UNIVERSITY 10 AGDA MARYLOU TADIFA MINDANAO STATE UNIVERSITY-MARAWI CITY 11 AGNIR LAARNI FONGFAR UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN MINDANAO-KABACAN 12 AGUA ARCHEL LEONO CENTRAL MINDANAO UNIVERSITY 13 AGUILA ANGELICA ESCOBAL NOTRE DAME OF MARBEL UNIVERSITY 14 AGUIRRE CHARLO DEOCARES NOTRE DAME OF MARBEL UNIVERSITY 15 ALAMBATIN CARYL FRANCHETE CUBILLAN MINDANAO UNIVERSITY OF SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY-CDO 16 ALAMBATIN PETH TRIXIA BROOXS CUBILLAN MINDANAO UNIVERSITY OF SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY-CDO 17 ALASAGAS BRYAN ARAGAN MINDANAO STATE UNIVERSITY-ILIGAN INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY 18 ALCALDE LOREN GRACE JUMILLA DAVAO DOCTORS COLLEGE, INC. 19 ALCANZAR CHARISSA JULIENNE BIAG ATENEO DE DAVAO UNIVERSITY 20 ALCISTO ROMELYN BERCERO MINDANAO STATE UNIVERSITY-ILIGAN INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY 21 ALCOVER JEZEIL JALANDONI MINDANAO UNIVERSITY OF SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY-CDO 22 ALEGADO WRYAN CORDEL NEBRIJA MINDANAO STATE UNIVERSITY-ILIGAN INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY 23 ALERTA ESTER NICE TILOS MINDANAO UNIVERSITY OF SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY-CDO 24 ALIMASAG JOHNEL BASMAYOR MINDANAO STATE UNIVERSITY-ILIGAN INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY REMINDER: USE SAME NAME IN ALL EXAMINATION FORMS. -

Republic of the Philippines ENERGY REGULATORY COMMISSION San Miguel Avenue, Pasig City

Republic of the Philippines ENERGY REGULATORY COMMISSION San Miguel Avenue, Pasig City IN THE MATTER OF THE JOINT APPLICATION FOR APPROVAL OF THE ELECTRICITY SUPPLY AND TRANSFER AGREEMENT BETWEEN THE DAVAO ORIENTAL ELECTRIC COOPERATIVE, INC. AND SUPREME POWER CORP., WITH PRAYER FOR ISSUANCE OF A PROVISIONAL AUTHORITY/ INTERIM RELIEF ERC CASE NO. 2020-002 RC DAVAO ORIENTAL Promulgated: ELECTRIC COOPERATIVE, August 24, 2020 INC. AND SUPREME POWER CORP., Joint Applicants. x -------------------------------------- x NOTICE OF VIRTUAL HEARING TO ALL INTERESTED PARTIES: Notice is hereby given that on 10 January 2020, Davao Oriental Electric Cooperative, Inc. (DORECO) and Supreme Power Corp. (Supreme) filed a Joint Application dated 06 December 2019, seeking the Commission’s approval of their Electricity Supply and Transfer Agreement with prayer for provisional authority or interim relief. The pertinent allegations of the said Joint Application are hereunder quoted as follows: Parties to the Case 1. Applicant DORECO is an electric cooperative duly organized and existing under and by virtue of the laws of the Republic of the Philippines, with principal office address at Madang, National Hi-way, Mati City, Davao Oriental. On 13 August ERC CASE NO. 2020-002 RC NOTICE OF VIRTUAL HEARING/ 17 AUGUST 2020 PAGE 2 OF 18 1980, DORECO was granted a fifty (50) year franchise by the National Electrification Commission (NEC) to distribute electric service in the City of Mati, and municipalities in the Province of Davao Oriental particularly Lupon, Banaybanay, San Isidro, Gov. Generoso, Tarragona, Manay, Caraga, Baganga, Cateel and Boston. A Copy of its NEC Certificate of Franchise, Articles of Incorporation, Certificate of Registration and 2018 Annual Report showing its current Board of Directors is attached to this Application as Annexes “A”, “A-1”, “A-2” and “A-3” respectively and are all made an integral parts hereof. -

Sultan Kudarat Hon

=lDepartment of Health NATIONAL NUTRITION COUNCIL Region XII LIST OF LOCAL CHIEF EXECUTIVES and P/C NUTRITION ACTION OFFICERS Updated as of January 7, 2019 Provinces Local Chief Executives Name of NAO’s Office Address Contact No. Email Address Sarangani Hon. Steve Chiongbian-Solon Dr. Arvin C. Alejandro IPHO-Sarangani Province 083-508-2167 [email protected] Alabel, Sarangani 09393045621 South Cotabato Prov’ l. Social Welfare &Dev’t. 083-228-2184/ Hon. Daisy P. Avance- Fuentes Ms. Maria Ana D. Uy Office, Koronadal City, South 09266885635 [email protected] Cotabato Sultan Kudarat Hon. Datu Pax Mangudadatu Dr. Consolacion Lagamayo IPHO-Sultan Kudarat Province, 064-201-3032 [email protected] Isulan, Sultan Kudarat North Cotabato Hon. Emmylou ”Lala” Taliño- Mr. Ely M. Nebrija IPHO-Cotabato Province 064-572-5014 [email protected] Mendoza Amas, Kidapawan City 09090001911 [email protected] Cities Local Chief Executives Name of NAO’s Office Address Contact No. Email Address Cotabato City Hon. Frances Cynthia Guiani- Ms. Bai linang C. Abas Office on Health Services, 064-421-3140 [email protected] Sayadi Rosary Heights, Cotabato City 09161068896 [email protected] General Santos City Hon. Ronnel C. Rivera Dr. Rochelle G. Oco, MD, City Health Office, General 09427529747 MCHA Santos City Kidapawan City Hon. Joseph A. Evangelista Ms. Melanie S. Espina City Nutrition Office, 064- 5771-377/ Kidapawan City 09482370612 [email protected] Koronadal City Hon. Peter B. Miguel, MD, FPSO- Ms. Veronica M. Daut City Nutrition Office, Koronadal 083-228-1763 HNS City 09498494864 Tacurong City Hon. Lina O. Montilla N/A City Social Welfare & Dev’t 064-200-4915 [email protected] Office, Tacurong City 09296096884 List of Local Chief Executives & Municipal Nutrition Action Officers (SOUTH COTABATO) Municipality Mayor Name of NAO’s Office Address Contact No. -

Press Release

Republic of the Philippines Philippine Statistics Authority PRESS RELEASE First Quarter 2020 PSGC Updates: One New Barangay Created, Names of Two Barangays Corrected Date of Release: 05 May 2020 Reference No. 2020-079 During the first quarter of 2020, the creation of Barangay Lacnog West was ratified through a plebiscite held on 22 February 2020 pursuant to Republic Act No. 11328 – “An Act Separating the Sitios of Guina-ang, Madopdop, Mallango, Lanlana and San Pablo from Barangay Lacnog, City of Tabuk, Province of Kalinga and Constituting Them into a Separate and Independent Barangay to be Known as Barangay Lacnog West." Meanwhile, the names of two (2) barangays in the City of Tacurong in Sultan Kudarat were corrected in the same period. The names of Barangay Lower Katungal and Barangay Gansing were changed into Barangay Enrique JC Montilla per Municipal Ordinance No. 39 dated 17 October 1990 and Barangay Virginia Griño per Sangguniang Panlalawigan Resolution No. 176-2nd SP-82 dated 17 November 1982, respectively. The National Historical Commission of the Philippines (NHCP) also affirmed the validity of the legal bases cited above. With the above updates, the total number of barangays in the country reached 42,046 barangays while the number of regions, provinces, cities, and municipalities remained the same as shown below: Geographic-level As of 31 March 2020 As of 31 December 2019 Region 17 17 Province 81 81 City 146 146 Municipality 1,488 1,488 Barangay 42,046 42,045 The compilation and updating of the PSGC is a collaborative effort of the Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA) and its interagency Technical Working Group on Geographic Code (TWGGC) composed of the Department of the Interior and Local Government (DILG), Commission on Elections (COMELEC), National Mapping and Resource Information Authority (NAMRIA), and the Land Management Bureau (LMB).