Aboriginal History of the Waverley Area

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cooks River Valley Association Inc. PO Box H150, Hurlstone Park NSW 2193 E: [email protected] W: ABN 14 390 158 512

Cooks River Valley Association Inc. PO Box H150, Hurlstone Park NSW 2193 E: [email protected] W: www.crva.org.au ABN 14 390 158 512 8 August 2018 To: Ian Naylor Manager, Civic and Executive Support Leichhardt Service Centre Inner West Council 7-15 Wetherill Street Leichhardt NSW 2040 Dear Ian Re: Petition on proposal to establish a Pemulwuy Cooks River Trail The Cooks River Valley Association (CRVA) would like to submit the attached petition to establish a Pemulwuy Cooks River Trail to the Inner West Council. The signatures on the petition were mainly collected at two events that were held in Marrickville during April and May 2018. These events were the Anzac Day Reflection held on 25 April 2018 in Richardson’s Lookout – Marrickville Peace Park and the National Sorry Day Walk along the Cooks River via a number of Indigenous Interpretive Sites on 26 May 2018. The purpose of the petition is to creatively showcase the history and culture of the local Aboriginal community along the Cooks River and to publicly acknowledge the role of Pemulwuy as “father of local Aboriginal resistance”. The action petitioned for was expressed in the following terms: “We, the undersigned, are concerned citizens who urge Inner West Council in conjunction with Council’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Reference Group (A&TSIRG) to designate the walk between the Aboriginal Interpretive Sites along the Cooks River parks in Marrickville as the Pemulwuy Trail and produce an information leaflet to explain the sites and the Aboriginal connection to the Cooks River (River of Goolay’yari).” A total of 60 signatures have been collected on the petition attached. -

2015 NSW Aboriginal Arts and Cultural Strategy Funding Recipients

NSW Aboriginal Arts and Cultural Strategy 2015-2018 Approved Funding Recipients for 2015 The following organisations have received funding from Arts NSW under Stage 2 of the NSW Aboriginal Arts and Cultural Strategy 2015-2018 Connection, Culture Pathways which builds on the Strategy’s achievements of the last 4 years. Approximately $850,278 in targeted funding was allocated through the NSW Aboriginal Arts and Cultural Strategy 2015-2018, Strategic Initiatives. Total funding to Aboriginal organisations and Aboriginal artistic projects in 2015 was $2,324,803, this includes funding from the Arts and Cultural Development Program (ACDP).The ACDP is focused on developing the quality, reach and health of the arts and cultural sector in NSW. The ACDP supports the Government’s new arts and cultural policy framework, Create in NSW, with engagement and participation with the following key priority area’s: People living and/or working in regional NSW; People living and/or working in Western Sydney; Aboriginal people; people from Culturally and Linguistically Diverse (CaLD) backgrounds; Young people and People with disability. Organisation Project title Description Amount Arts North West Inc. Creative Freedom Curator – Aboriginal A regional NSW Aboriginal Creative Freedom Curator will be engaged to enhance the $15,000 Cultural Showcase professional and skills development of Aboriginal performers and artists, guiding them to explore and express their cultural identities and deliver the opening ceremony for the 2016 Aboriginal Cultural Showcase. Bundanon Trust Transmit Art and Banner Project The TRANSMIT Art-and-Banner project is a four-day intensive residency and $8,500 mentorship project at Bundanon Trust involving artists from the Aboriginal Cultural Arts Program, Illawarra TAFE, Nowra Campus and young people disengaged from school. -

Indigenous Community Protocols for Bankstown Area Multicultural Network

INDIGENOUS COMMUNITY PROTOCOLS FOR BAMN MANAGEMENT COMMITTEE Practical protocols for working with the Indigenous Community of South West Sydney 1 Contents RESPECT, ACKNOWLEDGE, LISTEN Practical protocols for working with Indigenous communities in Western Sydney What are protocols? 1. Get To Know Your Indigenous Community Identity Diversity – Different rules for different community groups (there can sometimes be different groups within communities) 2. Consult Indigenous Reference Groups, Steering Committees and Boards 3. Get Permission The Local Community Elders Traditional Owners Ownership Copyright and Indigenous Cultural and Intellectual Property 4. Communicate Language Koori Time Report back and stay in touch 5. Ethics and Morals Confidentiality Integrity and trust 6. Correct Procedures Respect What to call people Traditional Welcome or Welcome to Country Acknowledging Traditional Owners Paying People Indigenous involvement Cross Cultural Training 7. Indigenous Organisations and Western Sydney contacts Major Indigenous Organisations Local Aboriginal Land Councils Indigenous Corporations/Community Organisations Indigenous Council, Community and Arts workers 8. Keywords to Remember 9. Other Protocol Resource Documents 2 What Are Protocols? Protocols can be classified as a set of rules, regulations, processes, procedures, strategies, or guidelines. Protocols are simply the ways in which you work with people, and communicate and collaborate with them appropriately. They are a guide to assist you with ways in which you can work, communicate and collaborate with the Indigenous community of Western Sydney. A wealth of Indigenous protocols documentation already exists (see Section 9), but to date the practice of following them is not widespread. Protocols are also standards of behaviour, respect and knowledge that need to be adopted. You might even think of them as a code of manners to observe, rather than a set of rules to obey. -

2019–20 Waverley Council Annual Report

WAVERLEY COUNCIL ANNUAL REPORT 2019–20 Waverley Council 3 CONTENTS Preface 04 Part 3: Meeting our Additional Mayor's Message 05 Statutory Requirements 96 General Manager's Message 07 Amount of rates and charges written off during the year 97 Our Response to COVID-19 and its impact on the Operational Plan and Budget 09 Mayoral and Councillor fees, expenses and facilities 97 Part 1: Waverley Council Overview 11 Councillor induction training and Our Community Vision 12 ongoing professional development 98 Our Local Government Area (LGA) Map 13 General Manager and Senior Waverley - Our Local Government Area 14 Staff Remuneration 98 The Elected Council 16 Overseas visit by Council staff 98 Advisory Committees 17 Report on Infrastructure Assets 99 Our Mayor and Councillors 18 Government Information Our Organisation 22 (Public Access) 102 Our Planning Framework 23 Public Interest Disclosures 105 External bodies exercising Compliance with the Companion Waverley Council functions 25 Animals Act and Regulation 106 Partnerships and Cooperation 26 Amount incurred in legal proceedings 107 Our Financial Snapshot 27 Progress against Equal Employment Performance Ratios 29 Opportunity (EEO) Management Plan 111 Awards received 33 Progress report - Disability Grants and Donations awarded 34 Inclusion Action Plan 2019–20 118 Grants received 38 Swimming pool inspections 127 Sponsorships received 39 Works undertaken on private land 127 Recovery and threat abatement plans 127 Part 2: Delivery Program Environmental Upgrade Agreements 127 Achievements 40 Voluntary -

The Builders Labourers' Federation

Making Change Happen Black and White Activists talk to Kevin Cook about Aboriginal, Union and Liberation Politics Kevin Cook and Heather Goodall Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://epress.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Cook, Kevin, author. Title: Making change happen : black & white activists talk to Kevin Cook about Aboriginal, union & liberation politics / Kevin Cook and Heather Goodall. ISBN: 9781921666728 (paperback) 9781921666742 (ebook) Subjects: Social change--Australia. Political activists--Australia. Aboriginal Australians--Politics and government. Australia--Politics and government--20th century. Australia--Social conditions--20th century. Other Authors/Contributors: Goodall, Heather, author. Dewey Number: 303.484 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover images: Kevin Cook, 1981, by Penny Tweedie (attached) Courtesy of Wildlife agency. Aboriginal History Incorporated Aboriginal History Inc. is a part of the Australian Centre for Indigenous History, Research School of Social Sciences, The Australian National University and gratefully acknowledges the support of the School of History RSSS and the National Centre for Indigenous Studies, The Australian National -

Re-Awakening Languages: Theory and Practice in the Revitalisation Of

RE-AWAKENING LANGUAGES Theory and practice in the revitalisation of Australia’s Indigenous languages Edited by John Hobson, Kevin Lowe, Susan Poetsch and Michael Walsh Copyright Published 2010 by Sydney University Press SYDNEY UNIVERSITY PRESS University of Sydney Library sydney.edu.au/sup © John Hobson, Kevin Lowe, Susan Poetsch & Michael Walsh 2010 © Individual contributors 2010 © Sydney University Press 2010 Reproduction and Communication for other purposes Except as permitted under the Act, no part of this edition may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or communicated in any form or by any means without prior written permission. All requests for reproduction or communication should be made to Sydney University Press at the address below: Sydney University Press Fisher Library F03 University of Sydney NSW 2006 AUSTRALIA Email: [email protected] Readers are advised that protocols can exist in Indigenous Australian communities against speaking names and displaying images of the deceased. Please check with local Indigenous Elders before using this publication in their communities. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Re-awakening languages: theory and practice in the revitalisation of Australia’s Indigenous languages / edited by John Hobson … [et al.] ISBN: 9781920899554 (pbk.) Notes: Includes bibliographical references and index. Subjects: Aboriginal Australians--Languages--Revival. Australian languages--Social aspects. Language obsolescence--Australia. Language revival--Australia. iv Copyright Language planning--Australia. Other Authors/Contributors: Hobson, John Robert, 1958- Lowe, Kevin Connolly, 1952- Poetsch, Susan Patricia, 1966- Walsh, Michael James, 1948- Dewey Number: 499.15 Cover image: ‘Wiradjuri Water Symbols 1’, drawing by Lynette Riley. Water symbols represent a foundation requirement for all to be sustainable in their environment. -

EORA Mapping Aboriginal Sydney 1770–1850 Exhibition Guide

Sponsored by It is customary for some Indigenous communities not to mention names or reproduce images associated with the recently deceased. Members of these communities are respectfully advised that a number of people mentioned in writing or depicted in images in the following pages have passed away. Users are warned that there may be words and descriptions that might be culturally sensitive and not normally used in certain public or community contexts. In some circumstances, terms and annotations of the period in which a text was written may be considered Many treasures from the State Library’s inappropriate today. Indigenous collections are now online for the first time at <www.atmitchell.com>. A note on the text The spelling of Aboriginal words in historical Made possible through a partnership with documents is inconsistent, depending on how they were heard, interpreted and recorded by Europeans. Original spelling has been retained in quoted texts, while names and placenames have been standardised, based on the most common contemporary usage. State Library of New South Wales Macquarie Street Sydney NSW 2000 Telephone (02) 9273 1414 Facsimile (02) 9273 1255 TTY (02) 9273 1541 Email [email protected] www.sl.nsw.gov.au www.atmitchell.com Exhibition opening hours: 9 am to 5 pm weekdays, 11 am to 5 pm weekends Eora: Mapping Aboriginal Sydney 1770–1850 was presented at the State Library of New South Wales from 5 June to 13 August 2006. Curators: Keith Vincent Smith, Anthony (Ace) Bourke and, in the conceptual stages, by the late Michael -

Ntscorp Limited Annual Report 2010/2011 Abn 71 098 971 209

NTSCORP LIMITED ANNUAL REPORT 2010/2011 ABN 71 098 971 209 Contents 1 Letter of Presentation 2 Chairperson’s Report 4 CEO’s Report 6 NTSCORP’s Purpose, Vision & Values 8 The Company & Our Company Members 10 Executive Profiles 12 Management & Operational Structure 14 Staff 16 Board Committees 18 Management Committees 23 Corporate Governance 26 People & Facilities Management 29 Our Community, Our Service 30 Overview of NTSCORP Operations 32 Overview of the Native Title Environment in NSW 37 NTSCORP Performing the Functions of a Native Title Representative Body 40 Overview of Native Title Matters in NSW & the ACT in 2010-2011 42 Report of Performance by Matter 47 NTSCORP Directors’ Report NTSCORP LIMITED Letter OF presentation THE HON. JennY MacKlin MP Minister for Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs Parliament House CANBERRA ACT 2600 Dear Minister, RE: 2010–11 ANNUAL REPORT In accordance with the Commonwealth Government 2010–2013 General Terms and Conditions Relating to Native Title Program Funding Agreements I have pleasure in presenting the annual report for NTSCORP Limited which incorporates the audited financial statements for the financial year ended 30 June 2011. Yours sincerely, MicHael Bell Chairperson NTSCORP NTSCORP ANNUAL REPORT 10/11 – 1 CHAIrperson'S Report NTSCORP LIMITED CHAIRPERSON’S REPORT The Company looks forward to the completion of these and other ON beHalF OF THE directors agreements in the near future. NTSCORP is justly proud of its involvement in these projects, and in our ongoing work to secure and members OF NTSCORP, I the acknowledgment of Native Title for our People in NSW. Would liKE to acKnoWledGE I am pleased to acknowledge the strong working relationship with the NSW Aboriginal Land Council (NSWALC). -

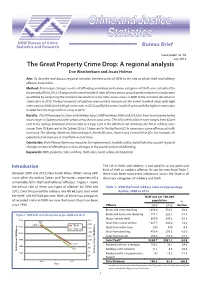

The Great Property Crime Drop: a Regional Analysis

NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research Bureau Brief Issue paper no. 88 July 2013 The Great Property Crime Drop: A regional analysis Don Weatherburn and Jessie Holmes Aim: To describe and discuss regional variation between parts of NSW in the rate at which theft and robbery offences have fallen. Method: Percentage changes in rates of offending in robbery and various categories of theft were calculated for the period 2000 to 2012. Changes in the extent to which rates of crime across areas have become more similar were quantified by comparing the standard deviation in crime rates across areas in 2000 to the standard deviation in crime rates in 2012. Product moment calculations were used to measure (a) the extent to which areas with high crime rates in 2000 also had high crime rates in 2012 and (b) the extent to which areas with the highest crime rates in 2000 had the largest falls in crime in 2012. Results: The fall in property crime and robbery across NSW between 2000 and 2012 has been very uneven; being much larger in Sydney and other urban areas than in rural areas. The fall in theft offence rates ranges from 62 per cent in the Sydney Statistical Division (SD) to 5.9 per cent in the Northern SD. Similarly, the fall in robbery rates ranges from 70.8 per cent in the Sydney SD to 21.9 per cent in the Northern SD. In some areas some offences actually increased. The Murray, Northern, Murrumbidgee, North Western, Hunter and Central West SDs, for example, all experienced an increase in steal from a retail store. -

Aboriginal Cultura

Category Applicant Title Funding Aboriginal Regional Arts Arts North West Inc Creative Freedom Curator - Aboriginal Cultural Showcase $15,000 Fund Aboriginal Regional Arts Bundanon Trust Transmit Art and Banner Project $8,500 Fund Aboriginal Regional Arts Byron Shire Council Season Styles – Bundjalung Arts Collective $15,000 Fund Aboriginal Regional Arts Eastern Riverina Arts 709.94R Aboriginal Art from Eastern Riverina $14,600 Fund Aboriginal Regional Arts Ferguson, Darryl Carving to Gamilaroi $3,000 Fund Aboriginal Regional Arts Fielding, Saretta Jane Mariyang Malang 'Onward Together' $3,000 Fund Aboriginal Regional Arts Flying Fruit Fly Foundation Burranha Bila Buraay (Bouncing River Kids) $15,000 Fund Aboriginal Regional Arts Hromek, Sian Christiane Creative development of Covered By Concrete for Underbelly $3,000 Fund Arts Festival Aboriginal Regional Arts Hubert Thomas Timbery Bidjigal Whale Dreaming project $3,000 Fund Aboriginal Regional Arts Keen, Warwick Patrick "Back to Burra Bee Dee" Photographic Exhibition $3,000 Fund Aboriginal Regional Arts Lismore City Council for Lismore Dreaming Trail: trading between Bundjalung and $15,000 Fund Regional Gallery Gumbaynggirr Aboriginal Regional Arts Murray Arts Inc Our Stories:Our Voices $15,000 Fund Aboriginal Regional Arts Shellharbour City Council Weaving Cultures $15,000 Fund Aboriginal Regional Arts South Coast Writers Centre SCWC Mentorship for Emerging Indigenous Writers $14,678 Fund Aboriginal Regional Arts Wagga Wagga City Council Panel Forum: Key cultural and political issues -

Practical Protocols for Working with the Indigenous Community of Western Sydney

CCD_RAL_bk.qxd 15/7/03 3:04 PM Page 1 CCD_RAL_Final.qxd 15/7/03 3:06 PM Page 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This project was assisted by the Government of NSW through the and The Federal Government through the Australia Council, its arts funding and advisory body. Researched and Written by This document is a project of the Angelina Hurley Indigenous Program of Indigenous Program Manager Community Cultural Development New Community Cultural Development NSW South Wales (CCDNSW) Draft Review and Copyright Section by © Community Cultural Development NSW Terri Janke Ltd, 2003 Principle Solicitor Terri Janke and Company Suite 8 54 Moore St. Design and Printing by Liverpool NSW 2170 MLC Powerhouse Design Studio PO Box 512 April 2003 Liverpool RC 1871 Ph: (02) 9821 2210 Cover Art Work Fax: (02) 9821 3460 ‘You Can’t Have Our Spirituality Without Web: www.ccdnsw.org Our Political Reality’ by Indigenous Artist Gordon Hookey Internal Art Work ‘Men’s Ceremony’ by Indigenous Artist Adam Hill CCD_RAL_Final.qxd 15/7/03 5:05 PM Page 2 Contents RESPECT, ACKNOWLEDGE, LISTEN: Practical protocols for working with the Indigenous Community of Western Sydney . .3 Who are Community Cultural Development New South Wales (CCDNSW)? What is ccd? . .3 What Are Protocols? . .3 1. Get To Know Your Indigenous Community . .4 Identity . .5 Diversity - Different Rules For Different Groups . .6 2. Consult . .6 Indigenous Reference Groups, Steering Committees and Boards . .7 3. Get Permission . .8 The Local Community . .8 Elders . .8 Traditional Owners . .8 Ownership . .9 Copyright And Indigenous Cultural And Intellectual Property . .9 4. Communicate . .10 Language . .10 Koori Time . -

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Protocols

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Protocols Adopted 1 August 2005 Table of Contents 1. Introduction .............................................................................. 1 2. What are Cultural Protocols?.................................................. 1 3. Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islanders....................................... 2 4. Aboriginality ............................................................................. 2 5. Brief History.............................................................................. 3 6. Respecting the Traditional Custodians.................................. 4 6.1 Traditional Custodians............................................................................4 6.2 Elders .....................................................................................................4 7. Significant Ceremonies ........................................................... 4 7.1 Welcome to Country...............................................................................4 7.2 Acknowledgement of Country.................................................................5 7.3 Smoking Ceremony................................................................................5 7.4 Fee for Service .......................................................................................5 8. Significant Dates ...................................................................... 6 8.1 Survival Day ...........................................................................................6 8.2 Harmony Day .........................................................................................7