Download (6Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Press Notes

Strand Releasing presents CECILE DE FRANCE - PATRICK BRUEL - LUDIVINE SAGNIER JULIE DEPARDIEU - MATHIEU AMALRIC A SECRET A FILM BY CLAUDE MILLER Based on the Philippe Grimbert novel "Un Secret" (Grasset & Fasquelle), English translation : "Memory, A Novel" (Simon and Schuster) Winner : 2008 César Award for Julie Depardieu (Best Actress in a Supporting Role) Grand Prix des Amériques, 2007 Montreal World Film Festival In French with English subtitles 35mm/1.85/Color/Dolby DTS/110 min NY/National Press Contact: LA/National Press Contact: Sophie Gluck / Sylvia Savadjian Michael Berlin / Marcus Hu Sophie Gluck & Associates Strand Releasing phone: 212.595.2432 phone: 310.836.7500 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Please download photos from our website: www.strandreleasing.com/pressroom/pressroom.asp 2 CAST Tania Cécile DE FRANCE Maxime Patrick BRUEL Hannah Ludivine SAGNIER Louise Julie DEPARDIEU 37-year-old François Mathieu AMALRIC Esther Nathalie BOUTEFEU Georges Yves VERHOEVEN Commander Beraud Yves JACQUES Joseph Sam GARBARSKI 7-year-old Simon Orlando NICOLETTI 7-year-old François Valentin VIGOURT 14-year-old François Quentin DUBUIS Robert Robert PLAGNOL Hannah's mother Myriam FUKS Hannah's father Michel ISRAEL Rebecca Justine JOUXTEL Paul Timothée LAISSARD Mathilde Annie SAVARIN Sly pupil Arthur MAZET Serge Klarsfeld Eric GODON Smuggler Philippe GRIMBERT 2 3 CREW Directed by Claude MILLER Screenplay, adaptation, dialogues by Claude MILLER and Natalie CARTER Based on the Philippe -

Before the Forties

Before The Forties director title genre year major cast USA Browning, Tod Freaks HORROR 1932 Wallace Ford Capra, Frank Lady for a day DRAMA 1933 May Robson, Warren William Capra, Frank Mr. Smith Goes to Washington DRAMA 1939 James Stewart Chaplin, Charlie Modern Times (the tramp) COMEDY 1936 Charlie Chaplin Chaplin, Charlie City Lights (the tramp) DRAMA 1931 Charlie Chaplin Chaplin, Charlie Gold Rush( the tramp ) COMEDY 1925 Charlie Chaplin Dwann, Alan Heidi FAMILY 1937 Shirley Temple Fleming, Victor The Wizard of Oz MUSICAL 1939 Judy Garland Fleming, Victor Gone With the Wind EPIC 1939 Clark Gable, Vivien Leigh Ford, John Stagecoach WESTERN 1939 John Wayne Griffith, D.W. Intolerance DRAMA 1916 Mae Marsh Griffith, D.W. Birth of a Nation DRAMA 1915 Lillian Gish Hathaway, Henry Peter Ibbetson DRAMA 1935 Gary Cooper Hawks, Howard Bringing Up Baby COMEDY 1938 Katharine Hepburn, Cary Grant Lloyd, Frank Mutiny on the Bounty ADVENTURE 1935 Charles Laughton, Clark Gable Lubitsch, Ernst Ninotchka COMEDY 1935 Greta Garbo, Melvin Douglas Mamoulian, Rouben Queen Christina HISTORICAL DRAMA 1933 Greta Garbo, John Gilbert McCarey, Leo Duck Soup COMEDY 1939 Marx Brothers Newmeyer, Fred Safety Last COMEDY 1923 Buster Keaton Shoedsack, Ernest The Most Dangerous Game ADVENTURE 1933 Leslie Banks, Fay Wray Shoedsack, Ernest King Kong ADVENTURE 1933 Fay Wray Stahl, John M. Imitation of Life DRAMA 1933 Claudette Colbert, Warren Williams Van Dyke, W.S. Tarzan, the Ape Man ADVENTURE 1923 Johnny Weissmuller, Maureen O'Sullivan Wood, Sam A Night at the Opera COMEDY -

The American Film Musical and the Place(Less)Ness of Entertainment: Cabaret’S “International Sensation” and American Identity in Crisis

humanities Article The American Film Musical and the Place(less)ness of Entertainment: Cabaret’s “International Sensation” and American Identity in Crisis Florian Zitzelsberger English and American Literary Studies, Universität Passau, 94032 Passau, Germany; fl[email protected] Received: 20 March 2019; Accepted: 14 May 2019; Published: 19 May 2019 Abstract: This article looks at cosmopolitanism in the American film musical through the lens of the genre’s self-reflexivity. By incorporating musical numbers into its narrative, the musical mirrors the entertainment industry mise en abyme, and establishes an intrinsic link to America through the act of (cultural) performance. Drawing on Mikhail Bakhtin’s notion of the chronotope and its recent application to the genre of the musical, I read the implicitly spatial backstage/stage duality overlaying narrative and number—the musical’s dual registers—as a means of challenging representations of Americanness, nationhood, and belonging. The incongruities arising from the segmentation into dual registers, realms complying with their own rules, destabilize the narrative structure of the musical and, as such, put the semantic differences between narrative and number into critical focus. A close reading of the 1972 film Cabaret, whose narrative is set in 1931 Berlin, shows that the cosmopolitanism of the American film musical lies in this juxtaposition of non-American and American (at least connotatively) spaces and the self-reflexive interweaving of their associated registers and narrative levels. If metalepsis designates the transgression of (onto)logically separate syntactic units of film, then it also symbolically constitutes a transgression and rejection of national boundaries. In the case of Cabaret, such incongruities and transgressions eventually undermine the notion of a stable American identity, exposing the American Dream as an illusion produced by the inherent heteronormativity of the entertainment industry. -

Feminisms 1..277

Feminisms The Key Debates Mutations and Appropriations in European Film Studies Series Editors Ian Christie, Dominique Chateau, Annie van den Oever Feminisms Diversity, Difference, and Multiplicity in Contemporary Film Cultures Edited by Laura Mulvey and Anna Backman Rogers Amsterdam University Press The publication of this book is made possible by grants from the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO). Cover design: Neon, design and communications | Sabine Mannel Lay-out: japes, Amsterdam Amsterdam University Press English-language titles are distributed in the US and Canada by the University of Chicago Press. isbn 978 90 8964 676 7 e-isbn 978 90 4852 363 4 doi 10.5117/9789089646767 nur 670 © L. Mulvey, A. Backman Rogers / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2015 All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. Contents Editorial 9 Preface 10 Acknowledgments 15 Introduction: 1970s Feminist Film Theory and the Obsolescent Object 17 Laura Mulvey PART I New Perspectives: Images and the Female Body Disconnected Heroines, Icy Intelligence: Reframing Feminism(s) and Feminist Identities at the Borders Involving the Isolated Female TV Detective in Scandinavian-Noir 29 Janet McCabe Lena Dunham’s Girls: Can-Do Girls, -

Entretien Avec François Ozon Michel Coulombe

Document generated on 09/27/2021 10:01 a.m. Ciné-Bulles Le cinéma d'auteur avant tout Entretien avec François Ozon Michel Coulombe Volume 19, Number 1, Fall 2000 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/33649ac See table of contents Publisher(s) Association des cinémas parallèles du Québec ISSN 0820-8921 (print) 1923-3221 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this document Coulombe, M. (2000). Entretien avec François Ozon. Ciné-Bulles, 19(1), 32–36. Tous droits réservés © Association des cinémas parallèles du Québec, 2000 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ Entretien avec i Ozon «Je provoque des réactions excessives: adhésion totale ou rejet total. » François Ozon PAR MICHEL COULOMBE Comme bien des réalisateurs, François Ozon n'aime pas particulièrement assurer la promotion de Ses films. Le service après-vente, très peu pour lui. Surtout que le prochain film n'est jamais très loin. Ayant exploré le circuit des festivals avec ses courts métrages puis avec son premier long métrage, Sitcom, de son propre aveu, il sature. Mais voilà, Bernard Giraudeau, la vedette de Gouttes d'eau sur pierres brûlantes, ne voyage pas. Aussi lui a-t-il fallu faire trois petits tours au Festival des films du monde pour parler de son adaptation de la pièce de Rainer Werner Fassbinder, cette curieuse histoire de Leopold, vieux beau qui rencontre le jeune Franz qui renoncera à épouser Anna pour vivre avec lui, quoiqu'il soit impossible en ménage, comme peut d'ailleurs en témoigner la mystérieuse Véra qui revient, après des années, montrer la femme qu'elle est devenue pour lui plaire. -

DOC DE PRESS-V3.Indd

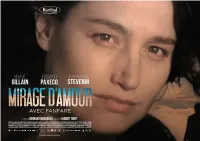

présente, Une production Saga Film Un film d’Hubert Toint Avec Marie Gillain, Jean-François Stévenin, Eduardo Paxeco 97 min • Belgique - France – Suisse • Scope • Couleur • 5.1 SORTIE LE 23 MARS 2016 DISTRIBUTION KANIBAL FILMS DISTRIBUTION DIRECTRICE DE LA DISTRIBUTION Arnaud Kerneguez Sylvie Grosperrin 10, rue du Colisée – 75008 Paris 01.79.36.01.03 01.47.24.75.22 [email protected] [email protected] Assistée de RELATIONS PRESSE Thomas Giezek Laurent Donzé 01 79 36 01 02 LD Communication [email protected] 06.63.84.62.26 [email protected] Matériel de presse téléchargeable sur www.kanibalfilms.fr Toute l’actualité du film sur Facebook : www.facebook.com/kanibalfilms Années 1920, dans le désert d’Acatama au nord du Chili se trouve Pampa-Terminal, une petite ville minière dans laquelle vivent des ouvriers de la mine, des cadres et quelques familles. Il y a une phar- macie, un théâtre ouvrier, une boulangerie, une boucherie. Il y a aussi des bordels dans la rue. Dans le cinéma de la ville, Hirondelle Rivery del Rosario (Marie Gil- lain) accompagne des films muets au piano. Elle vit chez son père, Alexandre Rivery (Jean-François Stévenin), un barbier anarchiste qui organise des réunions syndicales dans son salon de coiffure. Il faudra compter avec les élucubrations anarchistes d’Alexandre Rivery, les fantaisies amoureuses de Yémo, l’acrobate, les chaudes soirées au bordel de Cocoliche, la minutieuse constitution d’une fanfare et la répression violente d’un pouvoir dictatorial… Hirondelle responsable de la fanfare d’accueil pour l’arrivée du Pré- sident chilien va faire la connaissance de Bello Sandalio (Eduardo Paxeco). -

Download Detailseite

Wettbewerb/IFB 2000 GOUTTES D’EAU SUR PIERRES BRULANTES TROPFEN AUF HEISSE STEINE WATER DROPS ON BURNING ROCKS Regie: François Ozon Frankreich/Japan 1999 Darsteller Léopold Bernard Giraudeau Länge 90 Min. Franz Malik Zidi Format 35 mm, 1:1.66 Anna Ludivine Sagnier Farbe Véra Anna Thomson Stabliste Buch François Ozon,nach dem Bühnenstück von Rainer Werner Fassbinder Kamera Jeanne Lapoirie Schnitt Laurence Bawedin Ton Eric Devulder Ausstattung Arnaud de Moleron Kostüm Pascaline Chavanne Regieassistenz Hubert Bardin Produzent Marc Missonier Co-Produzent Kenzo Horikoshi Co-Produktion Euro Sage,Tokyo Produktion Fidélité Productions 13,rue Etienne Nascel F-75001 Paris Tel.:1-55 34 98 08 Fax:1-55 34 08 10 Weltvertrieb Roissy Films-Celluloid Dreams 24,rue Lamartine F-75009 Paris Tel.:1-49 70 09 85 Fax:1-49 70 85 60 Bernard Giraudeau TROPFEN AUF HEISSE STEINE Deutschland in den 70er Jahren. Léopold, 50 Jahre alt, Geschäftsmann, macht die Bekanntschaft von Franz, der 19 ist. Er lädt ihn zu sich ein. Eine Liebesgeschichte beginnt. Eines Tages folgt auf eine Lapalie eine Meinungsverschiedenheit.Von da ab gibt es kein gemeinsames „Wir“ mehr. WATER DROPS ON BURNING ROCKS Germany in the seventies. Léopold, a fifty-year-old businessman, meets Franz, who is nineteen. He invites him back to his place. A love affair begins. One day, something of little importance leads to a difference of opinion. And from this moment on, there’s no such thing as “we“ any more. GOUTTES D’EAU SUR PIERRES BRULANTES Filmografie Allemagne. Années soixante-dix. 1991 UNE GOUTE DE SANG Kurz-Video Léopold, 50 ans, représentant de commerce rencontre Franz, 19 ans. -

Film Film Film Film

City of Darkness, City of Light is the first ever book-length study of the cinematic represen- tation of Paris in the films of the émigré film- PHILLIPS CITY OF LIGHT ALASTAIR CITY OF DARKNESS, makers, who found the capital a first refuge from FILM FILMFILM Hitler. In coming to Paris – a privileged site in terms of production, exhibition and the cine- CULTURE CULTURE matic imaginary of French film culture – these IN TRANSITION IN TRANSITION experienced film professionals also encounter- ed a darker side: hostility towards Germans, anti-Semitism and boycotts from French indus- try personnel, afraid of losing their jobs to for- eigners. The book juxtaposes the cinematic por- trayal of Paris in the films of Robert Siodmak, Billy Wilder, Fritz Lang, Anatole Litvak and others with wider social and cultural debates about the city in cinema. Alastair Phillips lectures in Film Stud- ies in the Department of Film, Theatre & Television at the University of Reading, UK. CITY OF Darkness CITY OF ISBN 90-5356-634-1 Light ÉMIGRÉ FILMMAKERS IN PARIS 1929-1939 9 789053 566343 ALASTAIR PHILLIPS Amsterdam University Press Amsterdam University Press WWW.AUP.NL City of Darkness, City of Light City of Darkness, City of Light Émigré Filmmakers in Paris 1929-1939 Alastair Phillips Amsterdam University Press For my mother and father, and in memory of my auntie and uncle Cover design: Kok Korpershoek, Amsterdam Lay-out: japes, Amsterdam isbn 90 5356 633 3 (hardback) isbn 90 5356 634 1 (paperback) nur 674 © Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam, 2004 All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, me- chanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permis- sion of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. -

A World Like Ours: Gay Men in Japanese Novels and Films

A WORLD LIKE OURS: GAY MEN IN JAPANESE NOVELS AND FILMS, 1989-2007 by Nicholas James Hall A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES (Asian Studies) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) December 2013 © Nicholas James Hall, 2013 Abstract This dissertation examines representations of gay men in contemporary Japanese novels and films produced from around the beginning of the 1990s so-called gay boom era to the present day. Although these were produced in Japanese and for the Japanese market, and reflect contemporary Japan’s social, cultural and political milieu, I argue that they not only articulate the concerns and desires of gay men and (other queer people) in Japan, but also that they reflect a transnational global gay culture and identity. The study focuses on the work of current Japanese writers and directors while taking into account a broad, historical view of male-male eroticism in Japan from the Edo era to the present. It addresses such issues as whether there can be said to be a Japanese gay identity; the circulation of gay culture across international borders in the modern period; and issues of representation of gay men in mainstream popular culture products. As has been pointed out by various scholars, many mainstream Japanese representations of LGBT people are troubling, whether because they represent “tourism”—they are made for straight audiences whose pleasure comes from being titillated by watching the exotic Others portrayed in them—or because they are made by and for a female audience and have little connection with the lives and experiences of real gay men, or because they circulate outside Japan and are taken as realistic representations by non-Japanese audiences. -

In Concert at with Congregation Sha'ar Zahav

Street Theatre • Z. Budapest • Swingshift • Boy Meets Boy • C O M I N G U P ! FREE March, 1982 Largest Lesbian/Gay Circulation in the Bay Area The Mayor of Castro Street International Feminism Lesbian and Gay in Argentina Harvey Milk Lives! by Cris, an Argentine woman A review by Larry Lee International Women's Week officia lly classes. So these organizations arose runs from March 7 to U , bu t here In the Bay together with other revolutionary currents, The Mayor o f Castro Street: The Life & Times o f Harvey Milk, by Area It w ill start early and end late. A com not only In Argentina but throughout Latin Randy Shilts. St. M artin’s Press, 1982. $14.95. plete directory of events can be found on America. Later, many of these movements page 3. were destroyed by the military dictator In the three and a half years since the murder of Harvey Milk, To celebrate the week we've com m is ships that came to power. the columns have carried several items forecasting the way the sioned a number of special articles, In media would package his story, the inevitable fate o f our latter- cluding this one, which Inaugurates what During those years, In the 1970's, it was day heroes and martyrs. Joel Grey, o f all people, was Interested we hope w ill become an ongoing series on fashionable, especially In Buenos Aires, to in playing Harvey on TV, and there was talk o f a theatrical film the feminist, gay and lesbian movements go to gay clubs and bars. -

Kering and the Festival De Cannes Will Present the 2017 Women in Motion Award to Isabelle Huppert the Young Talents Award Will Be Presented to Maysaloun Hamoud

Kering and the Festival de Cannes will present the 2017 Women in Motion Award to Isabelle Huppert The Young Talents Award will be presented to Maysaloun Hamoud International film icon Isabelle Huppert will receive the third Women in MotionAward presented by Kering and the Festival de Cannes. Isabelle Huppert has chosen director and scriptwriter Maysaloun Hamoud to receive the Young Talents Award. François-Henri Pinault, Chairman and CEO of Kering, Pierre Lescure, President of the Festival de Cannes, and Thierry Frémaux, General Delegate of the Festival of Cannes, will present these awards during the official Women in Motion dinner on Sunday, 21 May 2017. Credits: Brigitte Lacombe For the third Women in Motion programme, official partner Kering and the Festival de Cannes will present the Women in Motion Award to French actress Isabelle Huppert. Exceptionally free-spirited and bold, Isabelle Huppert has taken many artistic risks in her career, and whilst acting with leading names, she has successfully established her own style in a variety of registers ranging from drama to comedy. She has pushed back boundaries with the strong and far-from-stereotypical roles that she has played since the early days of her career. Whether being directed by legendary filmmakers or by a brilliant new generation of talented filmmakers, Isabelle Huppert is one of the most inspirational figures in the world of cinema. Isabelle Huppert has in turn chosen to honour Maysaloun Hamoud by awarding her the Young Talents prize. In 2016 this young Palestinian director and scriptwriter made her first feature film, In Between (Bar Bahar), which chronicles the daily lives of three young Palestinian women living in Tel Aviv, torn between family traditions and their desire for independence. -

Film Appreciation Wednesdays 6-10Pm in the Carole L

Mike Traina, professor Petaluma office #674, (707) 778-3687 Hours: Tues 3-5pm, Wed 2-5pm [email protected] Additional days by appointment Media 10: Film Appreciation Wednesdays 6-10pm in the Carole L. Ellis Auditorium Course Syllabus, Spring 2017 READ THIS DOCUMENT CAREFULLY! Welcome to the Spring Cinema Series… a unique opportunity to learn about cinema in an interdisciplinary, cinematheque-style environment open to the general public! Throughout the term we will invite a variety of special guests to enrich your understanding of the films in the series. The films will be preceded by formal introductions and followed by public discussions. You are welcome and encouraged to bring guests throughout the term! This is not a traditional class, therefore it is important for you to review the course assignments and due dates carefully to ensure that you fulfill all the requirements to earn the grade you desire. We want the Cinema Series to be both entertaining and enlightening for students and community alike. Welcome to our college film club! COURSE DESCRIPTION This course will introduce students to one of the most powerful cultural and social communications media of our time: cinema. The successful student will become more aware of the complexity of film art, more sensitive to its nuances, textures, and rhythms, and more perceptive in “reading” its multilayered blend of image, sound, and motion. The films, texts, and classroom materials will cover a broad range of domestic, independent, and international cinema, making students aware of the culture, politics, and social history of the periods in which the films were produced.