The Cycles of Constitutional Theory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jonathan Capehart

Jonathan Capehart Award-winning journalist Jonathan Capehart is anchor of The Sunday Show with Jonathan Capehart on MSNBC and also an opinion writer and member of the editorial board of The Washington Post, where he hosts the podcast, Cape Up. In 1999, he was on the editorial board at the New York Daily News that won a Pulitzer Prize for the paper’s series of editorials that helped save Harlem’s Apollo Theater. He was also named an Esteem Honoree in 2011. In 2014, The Advocate magazine ranked him nineth out of fifty of the most influential LGBT people in media. In December 2014, Mediaite named him one of the “Top Nine Rising Stars of Cable News.” Equality Forum made him a 2018 LGBT History Month Icon in October. In May 2018, the publisher of the Washington Post awarded him an “Outstanding Contribution Award” for his opinion writing and “Cape Up” podcast interviews. Mr. Capehart first worked as assistant to the president of the WNYC Foundation. He then became a researcher for NBC's The Today Show. From 1993 to 2000, he served as a member of the New York Daily News’ editorial board. Mr. Capehart then went on to work as a national affairs columnist for Bloomberg News from 2000 to 2001, and later served as a policy advisor for Michael Bloomberg in his successful 2001 campaign for Mayor of New York City. In 2002, he returned to the New York Daily News, where he worked as deputy editorial page editor until 2004, when he was hired as senior vice president and senior counselor of public affairs for Hill & Knowlton. -

Programming Notes - First Read

Programming notes - First Read Hotmail More TODAY Nightly News Rock Center Meet the Press Dateline msnbc Breaking News EveryBlock Newsvine Account ▾ Home US World Politics Business Sports Entertainment Health Tech & science Travel Local Weather Advertise | AdChoices Recommended: Recommended: Recommended: 3 Recommended: First Thoughts: My, VIDEO: The Week remaining First Thoughts: How New iPads are Selling my, Myanmar That Was: Gifts, undecided House Rebuilding time for Under $40 fiscal cliff, and races verbal fisticuffs How Cruise Lines Fill All Those Unsold Cruise Cabins What Happens When You Take a Testosterone The first place for news and analysis from the NBC News Political Unit. Follow us on Supplement Twitter. ↓ About this blog ↓ Archives E-mail updates Follow on Twitter Subscribe to RSS Like 34k 1 comment Recommend 3 0 older3 Programming notes newer days ago *** Friday's "The Daily Rundown" line-up with guest host Luke Russert: NBC's Kelly O'Donnell on Petraeus' testimony… NBC's Ayman Mohyeldin live in Gaza… one of us (!!!) with more on the Republican reaction to Romney… NBC's Mike Viqueira on today's White House meeting on the fiscal cliff and The Economist's Greg Ip and National Journal's Jim Tankersley on the "what ifs" surrounding the cliff… New NRCC Chairman Rep. Greg Walden (R-OR) on the House GOP's road forward… Democratic strategist Doug Thornell, Roll Call's David Drucker and the New York Times' Jackie Calmes on how the next round of negotiations could be different (or all too similar) to the last time. Advertise | AdChoices *** Friday’s “Jansing & How to Improve Memory E-Cigarettes Exposed: Stony Brook Co.” line-up: MSNBC’s Chris with Scientifically Designed The E-Cigarette craze is sweeping the country. -

Reinforcing American Institutions: Why Americans Should Trust Media and the Judiciary

REINFORCING AMERICAN INSTITUTIONS: WHY AMERICANS SHOULD TRUST MEDIA AND THE JUDICIARY Sponsor: Office of the Kentucky Secretary of State CLE Credit: 1.0 Thursday, June 22, 2017 3:45 p.m. - 4:45 p.m. East Ballroom A-B Owensboro Convention Center Owensboro, Kentucky A NOTE CONCERNING THE PROGRAM MATERIALS The materials included in this Kentucky Bar Association Continuing Legal Education handbook are intended to provide current and accurate information about the subject matter covered. No representation or warranty is made concerning the application of the legal or other principles discussed by the instructors to any specific fact situation, nor is any prediction made concerning how any particular judge or jury will interpret or apply such principles. The proper interpretation or application of the principles discussed is a matter for the considered judgment of the individual legal practitioner. The faculty and staff of this Kentucky Bar Association CLE program disclaim liability therefore. Attorneys using these materials, or information otherwise conveyed during the program, in dealing with a specific legal matter have a duty to research original and current sources of authority. Printed by: Evolution Creative Solutions 7107 Shona Drive Cincinnati, Ohio 45237 Kentucky Bar Association TABLE OF CONTENTS The Presenters ................................................................................................................. i 2016 Kentucky Civic Health Index .................................................................................. -

The Privacy Panic Cycle: a Guide to Public Fears About New Technologies

The Privacy Panic Cycle: A Guide to Public Fears About New Technologies BY DANIEL CASTRO AND ALAN MCQUINN | SEPTEMBER 2015 Innovative new technologies often arrive on waves of breathless marketing Dire warnings about hype. They are frequently touted as “disruptive!”, “revolutionary!”, or the privacy risks associated with new “game-changing!” before businesses and consumers actually put them to technologies practical use. The research and advisory firm Gartner has dubbed this routinely fail to phenomenon the “hype cycle.” It is so common that many are materialize, yet conditioned to see right through it. But there is a corollary to the hype because memories cycle for new technologies that is less well understood and far more fade, the cycle of hysteria continues to pernicious. It is the cycle of panic that occurs when privacy advocates repeat itself. make outsized claims about the privacy risks associated with new technologies. Those claims then filter through the news media to policymakers and the public, causing frenzies of consternation before cooler heads prevail, people come to understand and appreciate innovative new products and services, and everyone moves on. Call it the “privacy panic cycle.” Dire warnings about the privacy risks associated with new technologies routinely fail to materialize, yet because memories fade, the cycle of hysteria continues to repeat itself. Unfortunately, the privacy panic cycle can have a detrimental effect on innovation. First, by alarming consumers, unwarranted privacy concerns can slow adoption of beneficial new technologies. For example, 7 out of 10 consumers said they would not use Google Glass, the now discontinued wearable head-mounted device, because of privacy concerns.1 Second, overwrought privacy fears can lead to ill-conceived policy responses that either THE INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY & INNOVATION FOUNDATION | SEPTEMBER 2015 PAGE 1 purposely hinder or fail to adequately promote potentially beneficial technologies. -

Download the Report

CENTER FOR GLOBAL POLICY SOLUTIONS ANNUAL REPORT 2014 WWW.GLOBALPOLICYSOLUTIONS.ORG 2014 ANNUAL REPORT LETTER FROM THE BOARD CHAIR AND PRESIDENT Dear CGPS Supporters: In 2012, we created the Center for Global Policy Solutions to engage and support transformative change for vulnerable populations through public policy. Our purpose is to make policy work for people and their environments within the areas of health, education, economic security, and civic engagement and across race, class, gender, and age. This “intersectional” approach reflects how the lives of people are lived and is the Center for Global Policy Solutions’ unique contribution to the field of policy research, programming, advocacy, and communications. In our third year of operation, we are proud of the significant strides we have made in protecting Social Security, educating policymakers and the public about the racial wealth gap, and helping to reverse the childhood obesity epidemic. We have measurable and powerful results in each of these areas, and look forward to expanding our reach, influence, and impact in years to come. We invite you to read our first annual report and share the stories of our success with others in your network interested in improving outcomes for our nation’s most vulnerable populations. Thank you for your time, interest, and support. BOARD CHAIR PRESIDENT AND CEO DR. CARROLL L. ESTES DR. MAYA ROCKEYMOORE 2014 ANNUAL REPORT WHO WE ARE The Center for Global Policy Solutions is a 501(c)(3) think income populations. In recognition of these overlapping tank and action organization that labors in pursuit of a identities and issues, we use an “intersectional” lens to vibrant, diverse, and inclusive world in which everyone develop policy and program solutions. -

Alison Dagnes

Alison Dagnes Department of Political Science, Shippensburg University Shippensburg, PA 17257 717-477-1754 [email protected] ________________________________________________________________________________________________ Curriculum Vita in Brief, Updated Spring 2019 Education University of Massachusetts Amherst, MA Ph.D. Political Science Fall, 2003 Dissertation: “White Noise: Media Use by Right Wing Extremist Groups for Political Purposes.” Committee Chair: Jerome Mileur Comprehensive Exam Fields: American National Government, American Political Institutions (Pass with Distinction), and Comparative Government St. Lawrence University Canton, NY B.A., Government Spring, 1991 Teaching Experience Shippensburg University Shippensburg, PA Professor Fall 2013 – Present Shippensburg University Student Association “Faculty Member of the Year 2014-2015” Associate Professor, Department of Political Science Fall 2008- Spring 2013 Shippensburg University Student Association “Faculty Member of the Year 2008-2009” Assistant Professor, Department of Political Science Fall, 2003 – Spring 2008 Shippensburg University Student Association “Faculty Member of the Year 2004-2005” Current Teaching Responsibilities: U.S. Government and Politics (PLS 100) African American Politics (PLS 325) Applications in Public Affairs (PLS 202) American Political Thought (PLS 363) Politics and the Media (PLS 321) Political Satire in Amer. Politics (PLS 393) Interest Groups in Society (PLS 322) Advocacy in Public Admin.(PLS 522) Campaigns, Elections & Political Parties (PLS 323) Publications: Sole-Authored Books Dagnes, Alison, Super Mad at Everything All the Time: Modern media & Our National Anger (New York: Palgrave) Forthcoming: Spring 2019. Dagnes, Alison, A Conservative Walks Into a Bar: The Politics of Political Humor (New York: Palgrave-Macmillan) 2012. Dagnes, Alison, Politics on Demand: The Effects of 24 Hour News on American Politics (Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger) 2010. -

Jeff Merkley's Dirty Smear Campaign Backfires

May 21, 2014 !! Washington Democrats in Panic Mode !! Call For All Hands On Deck Jeff Merkley's Dirty Smear Campaign Backfires Pediatric neurosurgeon Monica Wehby had an impressive victory last night, breaking the 50% mark in Oregon, a state where Democrats' panic has manifested itself in the most vicious personal attacks of the cycle thus far. Last night Dr. Wehby boldly stood up to her attackers. Democrats, who've insisted for months that they had absolutely no concerns about the Beaver State, have spent the last six days waging an ugly personal war against one of the most accomplished women running for elected office this cycle. On CNN, Gloria Borger explained the Democrats' overtly anti-woman strategy. "What do you do when you don't want a woman to win a Senate seat? You portray her as some kind of emotional wreck." It's that kind of hypocrisy that has people outraged. Yesterday on Ronan Farrow's MSNBC Show, columnist Heidi Moore explained the sexist nature of the Democrats' ugly attacks. "The way that we perceive women's actions is different... ...None of it is fair, and none of it is true, and that's the key thing. We are putting aside reality and misinterpreting women on purpose and I don't think women are saying enough about it." On MSNBC's Morning Joe, the panel agreed that Democrats were engaging in dirty politics. "Why are news people talking about this? It seems like an unbelievably cheap shot," Scarborough said before noting that, "Merkley is already saying she's deeply flawed, you know, the code stuff starts." Thomas Roberts agreed. -

Understanding the Cycles of Constitutional Time

Indiana Law Journal Volume 94 Issue 1 Article 6 Winter 2019 The Recent Unpleasantness: Understanding the Cycles of Constitutional Time Jack M. Balkin Yale Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ilj Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, Election Law Commons, Law and Politics Commons, Law and Society Commons, and the Legal History Commons Recommended Citation Balkin, Jack M. (2019) "The Recent Unpleasantness: Understanding the Cycles of Constitutional Time," Indiana Law Journal: Vol. 94 : Iss. 1 , Article 6. Available at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ilj/vol94/iss1/6 This Lecture is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Journals at Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Indiana Law Journal by an authorized editor of Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE RECENT UNPLEASANTNESS: UNDERSTANDING THE CYCLES OF CONSTITUTIONAL TIME JACK M. BALKIN* INTRODUCTION...................................................................................................... 253 I. THINKING IN TERMS OF CYCLES .................................................................... 254 II. THE CYCLE OF REGIMES ................................................................................ 258 A. WHERE ARE WE IN POLITICAL TIME? .................................................. 265 III. THE CYCLE OF POLARIZATION ...................................................................... -

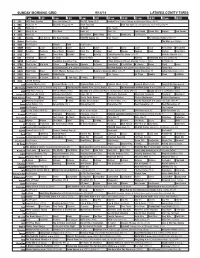

Sunday Morning Grid 9/14/14 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 9/14/14 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football New England Patriots at Minnesota Vikings. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å LPGA Tour Golf PGA Tour Golf Tour Championship, Final Round. (N) Å 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) Jack Hanna Ocean Mys. Explore Sea Rescue 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Winning Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Sunday (N) Paid Program The Ultimate Fighter (TV14) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program The Man ›› (2005) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local RescueBot RescueBot 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Cook Mexico Cooking Cook Kitchen Ciao Italia 28 KCET Hi-5 Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Celtic Thunder The Show (TVG) Å Irish the Musical (TVG) 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Hour of Power Paid Program Married Demolition Man ›› (1993) (R) 34 KMEX Paid Program República Deportiva (TVG) Fútbol Fútbol Mexicano Primera División: Pumas vs Tigres Al Punto (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Christ Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program 101 Dalmatians ›› (1996) Glenn Close. -

Bulletin an Affair to Remember

MAY/JUNE 2010 The Connecticut Association of Schools Affiliated with: The Connecticut Interscholastic Athletic Conference • National Federation of State High School Associations • National Association of Secondary School Principals • National Middle School Association • National Association of Elementary School Principals BULLETIN AN AFFAIR TO REMEMBER . eginning at 4:30 p.m. on Wednesday, May 26th, a steady stream of more than 400 guests - some from as far away as BCalifornia - filed into the Aqua Turf Club in Plantsville to celebrate the brilliant 50-year career of retiring executive director Mike Savage. As soon as the doors opened, eager well-wishers lined up to greet Mike, forming a queue that ultimately stretched all the way to the outdoors. It was a record-breaking hot spring night, and the temperature inside of Kay's Pier was almost as high as it was outside. But the heat served only to fuel the widespread energy and excitement to levels that were almost palpable. Friends, family members, colleagues and associates both past and present indulged in the magnificent array of foods that the Aqua Turf prepared and displayed with its usual standard of excellence. At 6:30 p.m., Mike was extricated from the still extant receiving NASSP Executive Director Gerry Tirozzi gives Mike a gentle line so that the formal recognition ceremony could begin. Master ribbing following his remarks. of Ceremonies Mike Buckley, associate executive director of CAS, began the program by reporting on the progress of Mike's cam- paign to raise funds to build a school in Haiti. He noted that a pro- posal had been developed, a design had been approved, philan- thropic partners presently working in Haiti – Brother's Brother and Food for the Poor – had been engaged, and more than $100,000 had been collected. -

In 2016 Name of the Game for GOP: “Obstructionism”

March 17, 2014 www.MRC.org Vol. 27, No. 6 Pick a Conservative and Get a “Goldwater Moment” in 2016 “You’re starting to get a picture of what 2016 could look like, what Iowa could look like, specifically. And it’s pretty darn fascinating. We’re starting to see here, guys, the fault lines of the battle for the soul of the GOP. Is it going to be a pragmatic governor in the Chris Christie form? Maybe if Jeb Bush gets involved, or maybe the Paul Ryan idea, Rubio. Or are we going Ted Cruz, are we going Rand Paul, and the GOP is going to have their 2016 Barry Goldwater moment? So, we shall see.” — MSNBC’s Luke Russert on The Cycle, March 6. Name of the Game for GOP: “Obstructionism” and “Toxic” Dialogue “What is your message to your party? Because even since from the time that you were there, obstruction- ism is just the name of the game for the Republican Party right now. And, obviously, that’s not leading to any meaningful progress. The dialogue is so toxic, because that’s all they have is the talk now, because they’re not doing anything.” — Co-anchor Chris Cuomo to former South Carolina Senator and Heritage Foundation President Jim DeMint on CNN’s New Day, March 4. Slamming Sarah Palin: A “Moron” and an “Ignorant, Two-Wheeled Bilewagon” MSNBC’s Mike Barnicle: “I have a question. The word ‘conservative’ can mean many things. I mean, there’s many definitions to it, but what does it say about a group, CPAC, where the most popular speaker they had, and the one who received the most rousing reception, is a moron, Sarah Palin? I mean, she received a recep- tion at that group that took the roof off the place. -

Public Affairs in the Time of Trump by Eric Bovim and Chelsea Koski Before He Was Elected President, Donald Trump the Candidate Was a Public Relations Revolutionary

Public Affairs in the Time of Trump By Eric Bovim and Chelsea Koski Before he was elected president, Donald Trump the candidate was a public relations revolutionary. With a genius for generating media—and often controversy—he racked up more free press than any of the candidates he ran against combined. Surprised? This was a candidate who spent more on those red “Make America Great Again” hats than he did on polling. Hillary Clinton’s stark advantages in money, campaign structure, surrogates, and grassroots organizing are well known. She should have won. Somehow, Trump’s pinpoint poll surges in stalwart Democratic states can partly be explained by his unorthodox communications style, which, by now, is well known as he enters his ninth month as president. He has transferred that iconoclastic approach from the campaign trail to the White House, but with mixed results and approval ratings hovering in the high thirties to low forties, depending on the poll. But this report is not an examination of how the 2016 election was surprisingly lost by Clinton, or a look at how Trump’s PR machine (and his heavy Twitter finger) may be damaging his favorability ratings and policy hopes. The political press corps is doing its best to explore these questions every day, even amidst claims by President Trump that much of its reportage is fake news. This report, instead, seeks to explore how President Trump’s unique PR style has totally disrupted Washington, rewriting the public affairs ground rules in the process. Below, we spell out some of the new principles for operating in the Trump White House.