Introduction 1 'Seeds and Roots/ 1893-1913

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

African Presses, Christian Rhetoric, and White Minority Rule in South Africa, 1899-1924

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2017 For the Good That We Can Do: African Presses, Christian Rhetoric, and White Minority Rule in South Africa, 1899-1924 Ian Marsh University of Central Florida Part of the African History Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Marsh, Ian, "For the Good That We Can Do: African Presses, Christian Rhetoric, and White Minority Rule in South Africa, 1899-1924" (2017). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 5539. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/5539 FOR THE GOOD THAT WE CAN DO: AFRICAN PRESSES, CHRISTIAN RHETORIC, AND WHITE MINORITY RULE IN SOUTH AFRICA, 1899-1924 by IAN MARSH B.A. University of Central Florida, 2013 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Summer Term 2017 Major Professor: Ezekiel Walker © 2017 Ian Marsh ii ABSTRACT This research examines Christian rhetoric as a source of resistance to white minority rule in South Africa within African newspapers in the first two decades of the twentieth-century. Many of the African editors and writers for these papers were educated by evangelical protestant missionaries that arrived in South Africa during the nineteenth century. -

Malibongwe Let Us Praise the Women Portraits by Gisele Wulfsohn

Malibongwe Let us praise the women Portraits by Gisele Wulfsohn In 1990, inspired by major political changes in our country, I decided to embark on a long-term photographic project – black and white portraits of some of the South African women who had contributed to this process. In a country previously dominated by men in power, it seemed to me that the tireless dedication and hard work of our mothers, grandmothers, sisters and daughters needed to be highlighted. I did not only want to include more visible women, but also those who silently worked so hard to make it possible for change to happen. Due to lack of funding and time constraints, including raising my twin boys and more recently being diagnosed with cancer, the portraits have been taken intermittently. Many of the women photographed in exile have now returned to South Africa and a few have passed on. While the project is not yet complete, this selection of mainly high profile women represents a history and inspiration to us all. These were not only tireless activists, but daughters, mothers, wives and friends. Gisele Wulfsohn 2006 ADELAIDE TAMBO 1929 – 2007 Adelaide Frances Tsukudu was born in 1929. She was 10 years old when she had her first brush with apartheid and politics. A police officer in Top Location in Vereenigng had been killed. Adelaide’s 82-year-old grandfather was amongst those arrested. As the men were led to the town square, the old man collapsed. Adelaide sat with him until he came round and witnessed the young policeman calling her beloved grandfather “boy”. -

Bird-Lore of the Eastern Cape Province

BIRD-LORE OF THE EASTERN CAPE PROVINCE BY REV. ROBERT GODFREY, M.A. " Bantu Studies " Monograph Series, No. 2 JOHANNESBURG WITWATERSRAND UNIVERSITY PRESS 1941 598 . 29687 GOD BIRD-LORE OF THE EASTERN CAPE PROVINCE BIRD-LORE OF THE EASTERN CAPE PROVINCE BY REV. ROBERT GODFREY, M.A. " Bantu Studies" Monograph .Series, No. 2 JOHANNESBURG WITWATERSRAND UNIVERSITY PRESS 1941 TO THE MEMORY OF JOHN HENDERSON SOGA AN ARDENT FELLOW-NATURALIST AND GENEROUS CO-WORKER THIS VOLUME IS AFFECTIONATELY DEDICATED. Published with the aid of a grant from the Inter-f University Committee for African Studies and Research. PREFACE My interest in bird-lore began in my own home in Scotland, and was fostered by the opportunities that came to me in my wanderings about my native land. On my arrival in South Africa in 19117, it was further quickened by the prospect of gathering much new material in a propitious field. My first fellow-workers in the fascinating study of Native bird-lore were the daughters of my predecessor at Pirie, Dr. Bryce Ross, and his grandson Mr. Join% Ross. In addition, a little arm y of school-boys gathered birds for me, supplying the Native names, as far as they knew them, for the specimens the y brought. In 1910, after lecturing at St. Matthew's on our local birds, I was made adjudicator in an essay-competition on the subject, and through these essays had my knowledge considerably extended. My further experience, at Somerville and Blythswood, and my growing correspondence, enabled me to add steadily to my material ; and in 1929 came a great opportunit y for unifying my results. -

![Upgrade of the R63-Section 13, Fort Beaufort [Km35.77] to Alice [Km58.86], Nkonkobe Local Municipality, Eastern Cape](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2255/upgrade-of-the-r63-section-13-fort-beaufort-km35-77-to-alice-km58-86-nkonkobe-local-municipality-eastern-cape-152255.webp)

Upgrade of the R63-Section 13, Fort Beaufort [Km35.77] to Alice [Km58.86], Nkonkobe Local Municipality, Eastern Cape

Phase 1 Archaeological & Cultural Heritage Impact Assessment – SANRAL: Upgrade of the R63-Section 13, Fort Beaufort [km35.77] to Alice [km58.86], Nkonkobe Local Municipality, Eastern Cape - 31 August 2016 - Report to: Sello Mokhanya (Eastern Cape Provincial Heritage Resources Agency – EC PHRA-APM Unit) E-mail: [email protected]; Tel: 043 745 0888; Postal Address: N/A Roy de Kock (EOH-Coastal & Environmental Services – EOH-CES) E-mail: [email protected]; Tel: 043 726 7809; Postal Address: P.O. Box 8145, Nahoon, East London, 5210 Prepared by: Karen van Ryneveld (ArchaeoMaps) E-mail: [email protected]; Tel: 084 871 1064; Postal Address: Postnet Suite 239, Private Bag X3, Beacon Bay, 5205 i Specialist Declaration of Interest I, Karen van Ryneveld (Company – ArchaeoMaps; Qualification – MSc Archaeology), declare that: o I am suitably qualified and accredited to act as independent specialist in this application; o I do not have any financial or personal interest in the application, its’ proponent or subsidiaries, aside from fair remuneration for specialist services rendered; and o That work conducted have been done in an objective manner – and that any circumstances that may have compromised objectivity have been reported on transparently. Signature – - 31 August 2016 - Phase 1 Archaeological & Cultural Heritage Impact Assessment – Upgrade of the R63-Section 13, Fort Beaufort-Alice and Utilization of Borrow Pits and a Quarry, Nkonkobe Local Municipality, Eastern Cape ArchaeoMaps ii Phase 1 Archaeological & Cultural Heritage Impact -

Anc Today Voice of the African National Congress

ANC TODAY VOICE OF THE AFRICAN NATIONAL CONGRESS 14 – 20 May 2021 Conversations with the President South Africa waging a struggle that puts global solidarity to the test n By President Cyril Ramaphosa WENTY years ago, South In response, representatives of massive opposition by govern- Africa was the site of vic- the pharmaceutical industry sued ment and civil society. tory in a lawsuit that pitted our government, arguing that such public good against private a move violated the Trade-Relat- As a country, we stood on princi- Tprofit. ed Aspects of Intellectual Property ple, arguing that access to life-sav- Rights (TRIPS). This is a compre- ing medication was fundamental- At the time, we were in the grip hensive multilateral agreement on ly a matter of human rights. The of the HIV/Aids pandemic, and intellectual property. case affirmed the power of trans- sought to enforce a law allowing national social solidarity. Sev- us to import and manufacture The case, dubbed ‘Big Pharma eral developing countries soon affordable generic antiretroviral vs Mandela’, drew widespread followed our lead. This included medication to treat people with international attention. The law- implementing an interpretation of HIV and save lives. suit was dropped in 2001 after the World Trade Organization’s Closing remarks by We are embracing Dear Mr President ANC President to the the future! Beware of the 12 NEC meeting wedge-driver: 4 10 Unite for Duma Nokwe 2 ANC Today CONVERSATIONS WITH THE PRESIDENT (WTO) Agreement on Trade-Re- ernment announced its support should be viewed as a global pub- lated Aspects of Intellectual Prop- for the proposal, which will give lic good. -

Cradock Four

Saif Pardawala 12/7/2012 TRC Cradock Four Amnesty Hearings Abstract: The Amnesty Hearing of the Truth and Reconciliation show the connection between the South African Apartheid state and the mysterious disappearances of four Cradock political activists. The testimonies of members of the security police highlight the lengths the apartheid state was willing to go to suppress opposition. The fall of Apartheid and the numerous examples of state mandated human rights abuses against its opponents raised a number of critical questions for South Africans at the time. Among the many issues to be addressed, was the need to create an institution for the restoration of the justice that had been denied to the many victims of apartheid’s crimes. Much like the numerous truth commissions established in Eastern Europe and Latin America after the formation of democracy in those regions, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was founded with the aims of establishing a restorative, rather than punitive justice. The goal of the TRC was not to prosecute and impose punishment on the perpetrators of the state’s suppression of its opposition, but rather to bring closure to the many victims and their families in the form of full disclosure of the truth. The amnesty hearings undertaken by the TRC represent these aims, by offering full amnesty to those who came forward and confessed their crimes. In the case of Johan van Zyl, Eric Taylor, Gerhardus Lotz, Nicholas van Rensburg, Harold Snyman and Hermanus du Plessis; the amnesty hearings offer more than just a testimony of their crimes. The amnesty hearings of the murderers of a group of anti-apartheid activists known as the Cradock Four show the extent of violence the apartheid state was willing to use on its own citizens to quiet any opposition and maintain its authority. -

Mandela at Wits University, South Africa, 1943–19491

UCLA Ufahamu: A Journal of African Studies Title “The Black Man in the White Man’s Court”: Mandela at Wits University, South Africa, 1943-1949 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3284d08q Journal Ufahamu: A Journal of African Studies, 39(2) ISSN 0041-5715 Author Ramoupi, Neo Lekgotla Laga Publication Date 2016 DOI 10.5070/F7392031110 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California “The Black Man in the White Man’s Court”: Mandela at Wits University, South Africa, 1943–19491 Neo Lekgotla laga Ramoupi* Figure 1: Nelson Mandela on the roof of Kholvad House in 1953. © Herb Shore, courtesy of Ahmed Kathrada Foundation. * Acknowledgements: I sincerely express gratitude to my former colleague at Robben Island Museum, Dr. Anthea Josias, who at the time was working for Nelson Mandela Foundation for introducing me to the Mandela Foundation and its Director of Archives and Dialogues, Mr. Verne Harris. Both gave me the op- portunity to meet Madiba in person. I am grateful to Ms. Carol Crosley [Carol. [email protected]], Registrar, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa, for granting me permission to use archival material from the Wits Archives on the premise that copyright is acknowledged in this publication. I appreciate the kindness from Ms. Elizabeth Nakai Mariam [Elizabeth.Marima@ wits.ac.za ], the Archivist at Wits for liaising with the Wits Registrar for granting usage permission. I am also thankful to The Nelson Mandela Foundation, espe- cially Ms. Sahm Venter [[email protected]] and Ms. Lucia Raadschel- ders, Senior Researcher and Photograph Archivist, respectively, at the Mandela Centre of Memory for bringing to my attention the Wits Archive documents and for giving me access to their sources, including the interview, “Madiba in conver- sation with Richard Stengel, 16 March 1993.” While visiting their offices on 6 Ja- nuary 2016 (The Nelson Mandela Foundation, www.nelsonmandela.org/.). -

Searchlight South Africa: a Marxist Journal of Southern African Studies Vol

Searchlight South Africa: a marxist journal of Southern African studies Vol. 2, No. 7 http://www.aluka.org/action/showMetadata?doi=10.5555/AL.SFF.DOCUMENT.PSAPRCA0009 Use of the Aluka digital library is subject to Aluka’s Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.aluka.org/page/about/termsConditions.jsp. By using Aluka, you agree that you have read and will abide by the Terms and Conditions. Among other things, the Terms and Conditions provide that the content in the Aluka digital library is only for personal, non-commercial use by authorized users of Aluka in connection with research, scholarship, and education. The content in the Aluka digital library is subject to copyright, with the exception of certain governmental works and very old materials that may be in the public domain under applicable law. Permission must be sought from Aluka and/or the applicable copyright holder in connection with any duplication or distribution of these materials where required by applicable law. Aluka is a not-for-profit initiative dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of materials about and from the developing world. For more information about Aluka, please see http://www.aluka.org Searchlight South Africa: a marxist journal of Southern African studies Vol. 2, No. 7 Alternative title Searchlight South Africa Author/Creator Hirson, Baruch; Trewhela, Paul; Ticktin, Hillel; MacLellan, Brian Date 1991-07 Resource type Journals (Periodicals) Language English Subject Coverage (spatial) Ethiopia, Iraq, Namibia, South Africa Coverage (temporal) -

4 August 2012 the President of the ANC Women`S League, Comrade

Address by ANC President Jacob Zuma on the occasion of the Charlotte Maxeke Memorial Lecture hosted by the ANC Women`s League to launch Women`s Month 4 August 2012 The President of the ANC Women`s League, Comrade Angie Motshekga, Free State Provincial Chairperson Comrade Ace Magashule, Leadership of the ANC Women`s League, Members of the ANC NEC, Vice‐Chancellor, Leadership and students of the University of the Free State, Distinguished Ladies and Gentlemen, Malibongwe! In a few days we will celebrate the 56th anniversary of the historical Women`s Month of 1956. That was the day when, at the height of apartheid, more than 20 000 women from all walks of life converged on the then forbidden grounds of the Union Buildings to present a petition against the extension of pass laws to women. The women reflected the whole spectrum of South African people, united in their diversity by one common goal at the time, to end the repressive pass laws. The 1956 Women`s March thus became one of the most important milestones in our struggle for freedom. But women`s activism did not start there. The struggles of women had begun much earlier. That is why we are gathered here today, to celebrate the life of the great Charlotte Maxeke, a pioneer, freedom fighter and women`s rights campaigner. This founding president of the Bantu Women`s League led the landmark women`s march against pass laws in 1913 in Bloemfontein. It is impressive that as early as 1913, women were already mobilising themselves into a formidable force which gave an example of courage and initiative. -

Throughout the 1950S the Liberal Party of South Africa Suffered Severe Internal Conflict Over Basic Issues of Policy and Strategy

Throughout the 1950s the Liberal Party of South Africa suffered severe internal conflict over basic issues of policy and strategy. On one level this stemmed from the internal dynamics of a small party unequally divided between the Cape, Transvaal and Natal, in terms of membership, racial composftion and political traditon. This paper and the larger work from which it is taken , however, argue inter alia that the conflict stemmed to a greater degree from a more fundamental problem, namely differing interpretations of liberalism and thus of the role of South African liberals held by various elements within the Liberal Party (LP). This paper analyses the political creed of those parliamentary and other liberals who became the early leaders of the LP. Their standpoint developed in specific circumstances during the period 1947-1950, and reflected opposition to increasingly radical black political opinion and activity, and retreat before the unfolding of apartheid after 1948. This particular brand of liberalism was marked by a rejection of extra- parliamentary activity, by a complete rejection of the univensal franchise, and by anti-communism - the negative cgaracteristics of the early LP, but also the areas of most conflict within the party. The liberals under study - including the Ballingers, Donald Molteno, Leo Marquard, and others - were all prominent figures. All became early leaders of the Liberal Party in 1953, but had to be *Ihijackedffigto the LP by having their names published in advance of the party being launched. The strategic prejudices of a small group of parliamentarians, developed in the 1940s, were thus to a large degree grafted on to non-racial opposition politics in the 1950s through an alliance with a younger generation of anti-Nationalists in the LP. -

From Mission School to Bantu Education: a History of Adams College

FROM MISSION SCHOOL TO BANTU EDUCATION: A HISTORY OF ADAMS COLLEGE BY SUSAN MICHELLE DU RAND Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts in the Department of History, University of Natal, Durban, 1990. TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Page i ABSTRACT Page ii ABBREVIATIONS Page iii INTRODUCTION Page 1 PART I Page 12 "ARISE AND SHINE" The Founders of Adams College The Goals, Beliefs and Strategies of the Missionaries Official Educational Policy Adams College in the 19th Century PART II Pase 49 o^ EDUCATION FOR ASSIMILATION Teaching and Curriculum The Student Body PART III Page 118 TENSIONS. TRANSmON AND CLOSURE The Failure of Mission Education Restructuring African Education The Closure of Adams College CONCLUSION Page 165 APPENDICES Page 170 BIBLIOGRAPHY Page 187 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my gratitude to my supervisor, Paul Maylam for his guidance, advice and dedicated supervision. I would also like to thank Michael Spencer, my co-supervisor, who assisted me with the development of certain ideas and in supplying constructive encouragement. I am also grateful to Iain Edwards and Robert Morrell for their comments and critical reading of this thesis. Special thanks must be given to Chantelle Wyley for her hard work and assistance with my Bibliography. Appreciation is also due to the staff of the University of Natal Library, the Killie Campbell Africana Library, the Natal Archives Depot, the William Cullen Library at the University of the Witwatersrand, the Central Archives Depot in Pretoria, the Borthwick Institute at the University of York and the School of Oriental and African Studies Library at the University of London. -

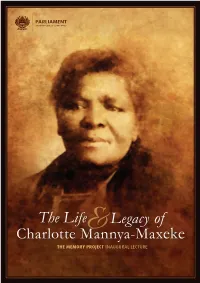

The Life Legacy of Charlotte Mannya-Max& Eke the MEMORY PROJECT INAUGURAL LECTURE the Life Legacy of Charlotte Mannya-Maxeke& the MEMORY PROJECT INAUGURAL LECTURE

The Life Legacy of Charlotte Mannya-Max& eke THE MEMORY PROJECT INAUGURAL LECTURE The Life Legacy of Charlotte Mannya-Maxeke& THE MEMORY PROJECT INAUGURAL LECTURE Contents Programme 3 Brief profile of Mme Charlotte Mmkgomo Mannya-Maxeke 4 Brief profile of Mme Gertrude Shope 10 Programme Director: Deputy Speaker, National Assembly, Mr Lechesa Tsenoli, MP TIME ACTIVITY RESPONSIBILITY 18:30 - 18:35 Musical Item SABC Choir 18:35 - 18:40 Opening & Welcome CEO of Freedom Park: Charlotte Mannya-Maxeke Ms. Jane Mufamadi 18:40 - 18:45 Remarks by Charlotte Mannya Director: Charlotte Mannya Maxeke Maxeke Institute for Girls Institute for Girls: Mr. Thulasizwe Makhanya 18:45 - 18:55 Message of Support CEO: Adv. Sonwabile Mancotywa, The Maxeke memory as living National Heritage Council heritage 19:00 - 19:10 Remarks on the Memory Speaker of the National Assembly: Project Hon. Baleka Mbete, MP Introduction of the Deputy President of the Republic of South Africa 19:10 – 19:25 Inauguration of the Memory Deputy President of the Republic of Project South Africa: Hon. Cyril Ramaphosa 19:25 - 19:30 Live Praise singing in honour Sepedi Praise Singer of Mme Charlotte Maxeke 19:30 – 19:35 Introduction of the Keynote Minister of Social Development: Speaker Hon. Bathabile Dlamini ANC Women’s League President 19:35 – 19:50 Keynote Address Mme Getrude Shope: Former Member of Parliament: (1994-1999) National Assembly Former ANC Women’s League President (1991-1993) 19:50 – 19:55 Presentation of Gift to Speaker of the National Assembly: Mme Shope Hon. Baleka Mbete, MP 19:55 – 20:00 Vote of thanks Hon RSS Morutoa Chairperson: Parliament Multi-party Women’s Caucus 3 Charlotte Mmkgomo Mannya- Maxeke She was the daughter of JONH KGOPE MANNYA, an ordinary man from Botloka village under Chief Mamafa Ramokgopa.