Royal Tern) Family: Laridae (Gulls and Terns) Order: Charadriiformes (Shorebirds and Waders) Class: Aves (Birds)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Order CHARADRIIFORMES: Waders, Gulls and Terns Suborder LARI

Text extracted from Gill B.J.; Bell, B.D.; Chambers, G.K.; Medway, D.G.; Palma, R.L.; Scofield, R.P.; Tennyson, A.J.D.; Worthy, T.H. 2010. Checklist of the birds of New Zealand, Norfolk and Macquarie Islands, and the Ross Dependency, Antarctica. 4th edition. Wellington, Te Papa Press and Ornithological Society of New Zealand. Pages 191, 223 & 227-228. Order CHARADRIIFORMES: Waders, Gulls and Terns The family sequence of Christidis & Boles (1994), who adopted that of Sibley et al. (1988) and Sibley & Monroe (1990), is followed here. Suborder LARI: Skuas, Gulls, Terns and Skimmers Condon (1975) and Checklist Committee (1990) recognised three subfamilies within the Laridae (Larinae, Sterninae and Megalopterinae) but this division has not been widely adopted. We follow Gochfeld & Burger (1996) in recognising gulls in one family (Laridae) and terns and noddies in another (Sternidae). The sequence of species for Stercorariidae and Laridae follows Peters (1934) and for Sternidae follows Bridge et al. (2005). Family LARIDAE Rafinesque: Gulls Laridia Rafinesque, 1815: Analyse de la Nature: 72 – Type genus Larus Linnaeus, 1758. Genus Larus Linnaeus Larus Linnaeus, 1758: Syst. Nat., 10th edition 1: 136 – Type species (by subsequent designation) Larus marinus Linnaeus. Gavia Boie, 1822: Isis von Oken, Heft 10: col. 563 – Type species (by subsequent designation) Larus ridibundus Linnaeus. Junior homonym of Gavia Moehring, 1758. Hydrocoleus Kaup, 1829: Skizz. Entw.-Gesch. Eur. Thierw.: 113 – Type species (by subsequent designation) Larus minutus Linnaeus. Chroicocephalus Eyton, 1836: Cat. Brit. Birds: 53 – Type species (by monotypy) Larus cucullatus Reichenbach = Larus pipixcan Wagler. Gelastes Bonaparte, 1853: Journ. für Ornith. -

Aspects of Breeding Behavior of the Royal Tern (Sterna Maxima) with Particular Emphasis on Prey Size Selectivity

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1984 Aspects of Breeding Behavior of the Royal Tern (Sterna maxima) with Particular Emphasis on Prey Size Selectivity William James Ihle College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the Zoology Commons Recommended Citation Ihle, William James, "Aspects of Breeding Behavior of the Royal Tern (Sterna maxima) with Particular Emphasis on Prey Size Selectivity" (1984). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625247. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-4aq2-2y93 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ASPECTS OF BREEDING BEHAVIOR OF THE ROYAL TERN (STERNA MAXIMA) n WITH PARTICULAR EMPHASIS ON PREY SIZE SELECTIVITY A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Biology The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by William J. Ihle 1984 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts 1MI \MLu Author Approved, April 1984 Mitchell A. Byrd m Stewart A. Ware R/ft R. Michael Erwin DEDICATION To Mom, for without her love and encouragement this thesis would not have been completed. FRONTISPIECE. Begging royal tern chick and its parent in the creche are surrounded by conspecific food parasites immediate!y after a feeding. -

Morphological Variation Among Herring Gulls (Larus Argentatus) and Great Black-Backed Gulls (Larus Marinus) in Eastern North America Gregory J

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of New England University of New England DUNE: DigitalUNE Environmental Studies Faculty Publications Environmental Studies Department 4-2016 Morphological Variation Among Herring Gulls (Larus Argentatus) And Great Black-Backed Gulls (Larus Marinus) In Eastern North America Gregory J. Robertson Environment Canada Sheena Roul Environment Canada Karel A. Allard Environment Canada Cynthia Pekarik Environment Canada Raphael A. Lavoie Queen's University See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: http://dune.une.edu/env_facpubs Part of the Ornithology Commons Recommended Citation Robertson, Gregory J.; Roul, Sheena; Allard, Karel A.; Pekarik, Cynthia; Lavoie, Raphael A.; Ellis, Julie C.; Perlut, Noah G.; Diamond, Antony W.; Benjamin, Nikki; Ronconi, Robert A.; Gilliland, Scott .;G and Veitch, Brian G., "Morphological Variation Among Herring Gulls (Larus Argentatus) And Great Black-Backed Gulls (Larus Marinus) In Eastern North America" (2016). Environmental Studies Faculty Publications. 22. http://dune.une.edu/env_facpubs/22 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Environmental Studies Department at DUNE: DigitalUNE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Environmental Studies Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DUNE: DigitalUNE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Authors Gregory J. Robertson, Sheena Roul, Karel A. Allard, Cynthia Pekarik, Raphael A. Lavoie, Julie C. Ellis, Noah G. Perlut, Antony W. Diamond, Nikki Benjamin, Robert A. Ronconi, Scott .G Gilliland, and Brian G. Veitch This article is available at DUNE: DigitalUNE: http://dune.une.edu/env_facpubs/22 Morphological Variation Among Herring Gulls (Larus argentatus) and Great Black-Backed Gulls (Larus marinus) in Eastern North America Author(s): Gregory J. -

Non-Living (Abiotic) Elements Shape Habitat

Forest Birds Fast Facts LIGHT: Dominated by tall trees, layered canopy = very shady, openings made from a fallen tree provide sunny areas AIR: Trees slow wind, except along forest edges and openings. Shade = cool temps WATER: Fog and rain collect in tree branches and drip to ground. SOIL: Lots of organics (needles, decaying leaves, tree trunks) makes lots of space for air and water. Soil absorbs and holds water like a sponge. Varied Thrush • Slender bill good at gleaning soft foods like insects, pillbugs, snails, worms, fruits and some seeds from ground. • Hops and pauses to look for food. Flips leaves and debris with bill. • Perching feet – three toes forward, hind toe back. • Can sing 2 separate notes at same time and breathe while singing. Common Raven Varied Thrush • Versatile beak. Eats everything from carrion and garbage, to eggs, nestlings, insects, seeds, rodents and fruit. • Strong, sturdy feet and grasping toes to manipulate food and perch. • Acrobatic flight, hops on ground. Uses sight to find food. Northern Flicker • The toes are placed two forward, two back to grip firmly, while the tail feathers are stiff and pointed to help brace while pounding. • Bill is shaped like a chisel. Flickers don’t excavate as much as other types of woodpeckers so have a slightly curved bill and less sharp. Common Raven • Flickers eat insects and are especially fond of ants (flickers will forage on the ground as well as on trees). Probe and explore crevices. • Distinctive flight – flap, dip, flap, dip • Woodpeckers have long, sticky and barbed tongues to extract bugs. -

Caspian Tern Nesting in South Carolina

CASPIAN TERN NESTING IN SOUTH CAROLINA TRAVIS H. McDANIEL and THEODORE A. BECKETT III Although the Caspian Tern (Hydroprogne caspia) is known to be a year-round resident of South Carolina, the 1970 edition of South Carolina Bird Life (p. 608) lists it as a non-breeding species because no nest or eggs have been collected in the state. E. Milby Burton, T.A. Beckett III, and others who have studied the colonial birds breeding on the islands along the coast of South Carolina during the past 50 years have never found a Caspian Tern nest or chick. Wayne's statement that the species nests in the Royal Tern colonies at Cape Romain (Birds of South Carolina, 1910, p. 4) has been widely accepted, though in retrospect it appears to have been based upon questionable information received from others rather than upon field work actually conducted by the distinguished ornithologist of Oakland Plantation near Mt. Pleasant. On 5 June 1970 Travis H. McDaniel, then manager at Cape Romain National Wildlife Refuge, made a routine check of nesting birds on Cape Island. As he walked through a Black Skimmer and Gull-billed Tern colony at the south end of the island, he noticed two tern eggs that were appreciably larger than those normally laid by Royal Terns, which are common nesters. During three years at Cape Romain, he had noted that Royal Terns usually lay only one egg. As McDaniel returned to his patrol truck, the birds began to settle back on their eggs. At this time he saw a very large tern dropping down from the air to settle on a nest despite harassing by Black Skimmers. -

Seabirds? What Seabirds?

Seabirds? What seabirds? An exploratory study into the origin of seabirds visiting the SE North Sea and their survival bottlenecks Mardik F. Leopold Publication date: 23 May 2017 Wageningen Marine Research Den Helder, May 2017 Wageningen Marine Research report C046/17 Mardik F. Leopold, 2016. Seabirds? What seabirds? An exploratory study into the origin of seabirds visiting the SE North Sea and their survival bottlenecks. Den Helder, Wageningen Marine Research (University & Research centre), Wageningen Marine Research report C046/17. Keywords: survival, dispersal, offshore wind farms. Client: Rijkswaterstaat / WVL Attn.: Maarten Platteeuw Zuiderwagenplein 2 8224 AD Lelystad This report can be downloaded, paper copies will not be forwarded https://doi.org/10.18174/416194 Wageningen Marine Research is ISO 9001:2008 certified. © 2017 Wageningen Marine Research Wageningen UR Wageningen Marine Research The Management of Wageningen Marine Research is not responsible for resulting institute of Stichting Wageningen damage, as well as for damage resulting from the application of results or Research is registered in the Dutch research obtained by Wageningen Marine Research, its clients or any claims traderecord nr. 09098104, related to the application of information found within its research. This report BTW nr. NL 806511618 has been made on the request of the client and is wholly the client's property. This report may not be reproduced and/or published partially or in its entirety without the express written consent of the client. A4_3_2_V24 2 -

Status and Distribution of the Laridae in Wyoming Through 1986

Great Basin Naturalist Volume 54 Number 4 Article 6 10-25-1994 Status and distribution of the Laridae in Wyoming through 1986 Scott L. Findholt Wyoming Game and Fish Department, Lander, Wyoming Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/gbn Recommended Citation Findholt, Scott L. (1994) "Status and distribution of the Laridae in Wyoming through 1986," Great Basin Naturalist: Vol. 54 : No. 4 , Article 6. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/gbn/vol54/iss4/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Western North American Naturalist Publications at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Basin Naturalist by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Creat Basin Naturalist 54(4), e 1994, pp. 34:2:-350 STATUS AD DISTRIBUTIO OF THE LARIDAE IN WYOMI 'G THROUGH 1986 Scott L. Findhoh1 A5~TR.-\n.-To date, 17 species of Laridae have been reported in Wyoming. Six of these species have known breed· ing populations in the state; the Rjng~hilled Gull (Lams delalkuren.sis), Califomia Gull (Larm colifamicus), Herring Gull (Lams argentatus), Caspian Tern {Sterna caspia), Forster's Tern (Stemaforsteri), and Black Tern (Chlidonias niger). Of these species, the California Cull is the most abundant and widespread. In 1984 approximately 1300 nests existed in \Vyoming at six breeding locations consisting of 10 different colonies. In contrast, only smllll breeding populations have been discovered for the remaining five species. The Herring Gull is the most recent addition among Laridae known to nest in Wyoming. -

Breeding Birds of the Texas Coast

Roseate Spoonbill • L 32”• Uncom- Why Birds are Important of the mon, declining • Unmistakable pale Breeding Birds Texas Coast pink wading bird with a long bill end- • Bird abundance is an important indicator of the ing in flat “spoon”• Nests on islands health of coastal ecosystems in vegetation • Wades slowly through American White Pelican • L 62” Reddish Egret • L 30”• Threatened in water, sweeping touch-sensitive bill •Common, increasing • Large, white • Revenue generated by hunting, photography, and Texas, decreasing • Dark morph has slate- side to side in search of prey birdwatching helps support the coastal economy in bird with black flight feathers and gray body with reddish breast, neck, and Chuck Tague bright yellow bill and pouch • Nests Texas head; white morph completely white – both in groups on islands with sparse have pink bill with Black-bellied Whistling-Duck vegetation • Preys on small fish in black tip; shaggy- • L 21”• Lo- groups looking plumage cally common, increasing • Goose-like duck Threats to Island-Nesting Bay Birds Chuck Tague with long neck and pink legs, pinkish-red bill, Greg Lavaty • Nests in mixed- species colonies in low vegetation or on black belly, and white eye-ring • Nests in tree • Habitat loss from erosion and wetland degradation cavities • Occasionally nests in mesquite and Brown Pelican • L 51”• Endangered in ground • Uses quick, erratic movements to • Predators such as raccoons, feral hogs, and stir up prey Chuck Tague other woody vegetation on bay islands Texas, but common and increasing • Large -

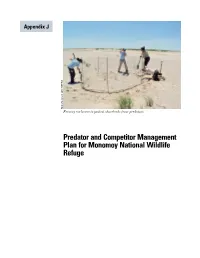

Predator and Competitor Management Plan for Monomoy National Wildlife Refuge

Appendix J /USFWS Malcolm Grant 2011 Fencing exclosure to protect shorebirds from predators Predator and Competitor Management Plan for Monomoy National Wildlife Refuge Background and Introduction Background and Introduction Throughout North America, the presence of a single mammalian predator (e.g., coyote, skunk, and raccoon) or avian predator (e.g., great horned owl, black-crowned night-heron) at a nesting site can result in adult bird mortality, decrease or prevent reproductive success of nesting birds, or cause birds to abandon a nesting site entirely (Butchko and Small 1992, Kress and Hall 2004, Hall and Kress 2008, Nisbet and Welton 1984, USDA 2011). Depredation events and competition with other species for nesting space in one year can also limit the distribution and abundance of breeding birds in following years (USDA 2011, Nisbet 1975). Predator and competitor management on Monomoy refuge is essential to promoting and protecting rare and endangered beach nesting birds at this site, and has been incorporated into annual management plans for several decades. In 2000, the Service extended the Monomoy National Wildlife Refuge Nesting Season Operating Procedure, Monitoring Protocols, and Competitor/Predator Management Plan, 1998-2000, which was expiring, with the intent to revise and update the plan as part of the CCP process. This appendix fulfills that intent. As presented in chapter 3, all proposed alternatives include an active and adaptive predator and competitor management program, but our preferred alternative is most inclusive and will provide the greatest level of protection and benefit for all species of conservation concern. The option to discontinue the management program was considered but eliminated due to the affirmative responsibility the Service has to protect federally listed threatened and endangered species and migratory birds. -

A Recently Formed Crested Tern (Thalasseus Bergii) Colony on a Sandbank in Fog Bay (Northern Territory), and Associated Predation

Northern Territory Naturalist (2015) 26: 13–16 Short Note A recently formed Crested Tern (Thalasseus bergii) colony on a sandbank in Fog Bay (Northern Territory), and associated predation Christine Giuliano1,2 and Michael L. Guinea1 1 Research Institute for the Environment and Livelihoods, Charles Darwin University, Darwin, NT 0909, Australia. Email: [email protected] 2 60 Station St, Sunbury, VIC 3429, Australia. Abstract A Crested Tern colony founded on a sandbank in northern Fog Bay (Northern Territory) failed in 1996 presumably due to inexperienced nesters. Attempts to breed in the years following were equally unsuccessful until 2012 when the colony was established. In 2014, the rookery comprised at least 1500 adults plus numerous chicks. With the success and growth of the colony, the predators, White-bellied Sea Eagles and Silver Gulls, were quick to capitalise on the new prey. Changes in the species diversity and numbers of the avifauna highlight the dynamic and fragile nature of life on the sandbanks of Fog Bay. Crested Terns (Thalasseus bergii) are the predominant colonial-nesting sea birds in the Northern Territory, with at least five islands supporting colonies of more than 30 000 nesting birds each year (Chatto 2001). These colonies have appeared stable over time with smaller satellite colonies located in the vicinity of the major rookeries. Silver Gulls (Chroicocephalus novaehollandiae) and White-bellied Sea Eagles (Haliaeetus leucogaster) prey heavily on the adults and chicks (Chatto 2001). In December 1989, Guinea & Ryan (1990) documented the avifauna and turtle nesting activity on Bare Sand Island (12°32'S, 130°25'E), a 20 ha sand dune island with low shrubs and a few trees. -

Dwergstern3.Pdf

99 PRIMARY MOULT, BODY MASS AND MOULT MIGRATION OF LITTLE TERN STERNAALBIFRONS IN NE ITALY GIUSEPPE CHERUBINI, LORENZO SERRA & NICOLA BACCETTI Cherubini G., L. Serra & N. Baccetti 1996. Primary moult, body mass and moult migration of Little Tern Sterna albifrons in NE Italy. Ardea 84: 99 114. Large post-breeding gatherings of Little Terns Sterna albifrons are regu larly observed in the Lagoon of Venice, Italy. Here, during five consecutive \ 1/ trapping seasons, 2956 birds were examined and ringed. Their breeding area, as indicated by 163 direct recoveries (mainly juveniles, ringed as chicks), spans over a broad sector of the Adriatic coasts, with colonies lo cated up to 133 km far. During their stay at the study area, adults undergo an almost complete moult. Two partial primary moult cycles can be ob \ served, the first of them being suspended when 2-4 outermost long primar ies have not yet been shed. Pre-migratory body mass build-up, enough for a ~/ flight longer than 1000 km, takes place during the very last days before de parture to the winter quarters, in most cases when the moult has reached a I suspended stage. Active primary moult and body mass increase do overlap in late moulting birds (after 27 August), indicating that the two processes are compatible, in case of time shortage. Post-breeding movements to the Lagoon of Venice seem to fit most requisites of moult migration. Key words: Sterna albifrons - Italy - biometrics - moult migration - ringing - fattening Istituto Nazionale per la Fauna Selvatica, via Ca' Fornacetta 9,1-40064 Oz zano Emilia BO, Italy. -

Lowrie, K., M. Friesen, D. Lowrie, and N. Collier. 2009. Year 1 Results Of

2009 Year 1 Results of Seabird Breeding Atlas of the Lesser Antilles Katharine Lowrie, Project Manager Megan Friesen, Research Assistant David Lowrie, Captain and Surveyor Natalia Collier, President Environmental Protection In the Caribbean 200 Dr. M.L. King Jr. Blvd. Riviera Beach, FL 33404 www.epicislands.org Contents INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................... 3 GENERAL METHODS ............................................................................................................................ 4 Field Work Overview ........................................................................................................................... 4 Water‐based Surveys ...................................................................................................................... 4 Data Recorded ................................................................................................................................. 5 Land‐based Surveys ......................................................................................................................... 5 Large Colonies ................................................................................................................................. 6 Audubon’s Shearwater .................................................................................................................... 7 Threats Survey Method .................................................................................................................