Rachmaninoff on Paganini Jan 23 & 24, 2021

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rachmaninoff's Rhapsody on a Theme By

RACHMANINOFF’S RHAPSODY ON A THEME BY PAGANINI, OP. 43: ANALYSIS AND DISCOURSE Heejung Kang, B.A., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2004 APPROVED: Pamela Mia Paul, Major Professor and Program Coordinator Stephen Slottow, Minor Professor Josef Banowetz, Committee Member Steven Harlos, Interim Chair of Piano Jessie Eschbach, Chair of Keyboard Studies James Scott, Dean of the College of Music Sandra L. Terrill, Interim Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Kang, Heejung, Rachmaninoff’s Rhapsody on a Theme by Paganini, Op.43: Analysis and Discourse. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2004, 169 pp., 40 examples, 5 figures, bibliography, 39 titles. This dissertation on Rachmaninoff’s Rhapsody on a Theme by Paganini, Op.43 is divided into four parts: 1) historical background and the state of the sources, 2) analysis, 3) semantic issues related to analysis (discourse), and 4) performance and analysis. The analytical study, which constitutes the main body of this research, demonstrates how Rachmaninoff organically produces the variations in relation to the theme, designs the large-scale tonal and formal organization, and unifies the theme and variations as a whole. The selected analytical approach is linear in orientation - that is, Schenkerian. In the course of the analysis, close attention is paid to motivic detail; the analytical chapter carefully examines how the tonal structure and motivic elements in the theme are transformed, repeated, concealed, and expanded throughout the variations. As documented by a study of the manuscripts, the analysis also facilitates insight into the genesis and structure of the Rhapsody. -

Operetta After the Habsburg Empire by Ulrike Petersen a Dissertation

Operetta after the Habsburg Empire by Ulrike Petersen A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge: Professor Richard Taruskin, Chair Professor Mary Ann Smart Professor Elaine Tennant Spring 2013 © 2013 Ulrike Petersen All Rights Reserved Abstract Operetta after the Habsburg Empire by Ulrike Petersen Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Berkeley Professor Richard Taruskin, Chair This thesis discusses the political, social, and cultural impact of operetta in Vienna after the collapse of the Habsburg Empire. As an alternative to the prevailing literature, which has approached this form of musical theater mostly through broad surveys and detailed studies of a handful of well‐known masterpieces, my dissertation presents a montage of loosely connected, previously unconsidered case studies. Each chapter examines one or two highly significant, but radically unfamiliar, moments in the history of operetta during Austria’s five successive political eras in the first half of the twentieth century. Exploring operetta’s importance for the image of Vienna, these vignettes aim to supply new glimpses not only of a seemingly obsolete art form but also of the urban and cultural life of which it was a part. My stories evolve around the following works: Der Millionenonkel (1913), Austria’s first feature‐length motion picture, a collage of the most successful stage roles of a celebrated -

The Merry Widow

the Merry widow SPARKLE AND SEDUCTION Renée Fleming stars in Susan Stroman’s sumptuous new production of Lehár’s The Merry Widow, a romance for grown-ups set against a glittering Belle Époque backdrop. By eric myers hen Franz Lehár’s The Merry Widow had its world premiere at Vienna’s Theater an der Wien on December 30, 1905, no one knew that it was ushering in the remarkable so-called “Silver Era” of Viennese oper- Wetta. Since the “Golden Era” of such 19th-century hits as Strauss’s The Gypsy Baron and Millöcker’s The Beggar Student, Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung had come to the fore, shaking up Europe’s attitudes toward sanity and sex. Vienna, newly clothed in the vines, tendrils, and flowing-haired maidens of Art Nouveau, had become a center of ideas and new artistic movements. There was no way that the popular young operetta composers of the day were going to remain unaffected. 46Renée | New Fleming Productio sings Nthes title role opposite Nathan Gunn. Photograph by Brigitte Lacombe New ProductioNs | 47 by enlisting him in the army, where, not surpris- power plays drive the story—but of course true ingly, Franz wound up playing in his father’s band. love conquers all.” At 20, he moved on to lead the Infantry Regiment Stroman too cites the operetta’s “sly romance Band in Hungary, becoming the youngest bandmas- and mistaken identity—the fun of it” as essential to ter in the Austro-Hungarian Empire. its ongoing allure, and she’s put together a remark- Before The Merry Widow, Lehár composed able creative team to bring out all the charm. -

2005-2006 the Sound of Vienna

LYNN UNIVERSITY CONSERVATORY OF MUSIC - PROGRAM THE SOUND OF VIENNA Dr. Jon Robertson, Milena Rudiferia, guest soprano Dean Welcome to the 2005-2006 season. This being my Lynn University Chamber Orchestra first year as dean of the conservatory, I greet the Sergiu Schwartz, conductor/violin season with unabated enthusiasm and excitement. The talented musicians and extraordinary performing Tao Lin, piano faculty at Lynn represent the future of the performing Kay Kemper, guest harpist arts, and you, the patrons, pave the road to their artistic success through your presence and generosity. This community engagement is in keeping with the Sponsored by Mr. And Mrs. S. K. Chan Conservatory of Music's mission: to provide high quality professional performance education for gifted young musicians and set a superior standard for Sunday, February 26, 2006 at 4 PM music performance worldwide. Amarnick-Goldstein Concert Hall Lynn University, Boca Raton THE ANNUAL FUND A gift to the Annual Fund can be designated for scholarships, various studios, special concerts or to the General Conservatory Fund. Antonin Dvorak ................................. Rusalka ADOPT-A-STUDENT (1841-1904) Song to the moon You may select from the conservatory's promising young musicians and provide for his or her future Jacques Offenbach ......... .... ............... .Les contes d'Hoffmann (1819-1880) Barcarolle: Belle nuit, o nuit d'amour through the Conservatory Scholarship Fund. You will enjoy the concert even more when your student Franz Lehar........................................ Paganini performs. A gift of $25,000 adopts a student for (1870-1948) Aria of Anna Elisa: Liebe, du Himmel auf one year. A gift of $100,000 pays for an education. -

Audition Repertoire, Please Contact the Music Department at 812.941.2655 Or by E-Mail at AUDITION REQUIREMENTS for VARIOUS DEGREE CONCENTRATIONS

1 AUDITION GUIDE AND SUGGESTED REPERTOIRE 1 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS AUDITION REQUIREMENTS AND GUIDE . 3 SUGGESTED REPERTOIRE Piano/Keyboard . 5 STRINGS Violin . 6 Viola . 7 Cello . 8 String Bass . 10 WOODWINDS Flute . 12 Oboe . 13 Bassoon . 14 Clarinet . 15 Alto Saxophone . 16 Tenor Saxophone . 17 BRASS Trumpet/Cornet . 18 Horn . 19 Trombone . 20 Euphonium/Baritone . 21 Tuba/Sousaphone . 21 PERCUSSION Drum Set . 23 Xylophone-Marimba-Vibraphone . 23 Snare Drum . 24 Timpani . 26 Multiple Percussion . 26 Multi-Tenor . 27 VOICE Female Voice . 28 Male Voice . 30 Guitar . 33 2 3 The repertoire lists which follow should be used as a guide when choosing audition selections. There are no required selections. However, the following lists illustrate Students wishing to pursue the Instrumental or Vocal Performancethe genres, styles, degrees and difficulty are strongly levels encouraged of music that to adhereis typically closely expected to the of repertoire a student suggestionspursuing a music in this degree. list. Students pursuing the Sound Engineering, Music Business and Music Composition degrees may select repertoire that is slightly less demanding, but should select compositions that are similar to the selections on this list. If you have [email protected] questions about. this list or whether or not a specific piece is acceptable audition repertoire, please contact the Music Department at 812.941.2655 or by e-mail at AUDITION REQUIREMENTS FOR VARIOUS DEGREE CONCENTRATIONS All students applying for admission to the Music Department must complete a performance audition regardless of the student’s intended degree concentration. However, the performance standards and appropriaterequirements audition do vary repertoire.depending on which concentration the student intends to pursue. -

Bienvenue Stéphane Mahler's Resurrection Rachmaninoff's Third

's 8 5 6 7 CONCERTS CONCERTS CONCERTS CONCERTS FRIDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY Coffee A B A B C D A B SEP Bienvenue Stéphane Stéphane Denève, conductor PUTS Virelai (World Premiere) Jean-Yves Thibaudet, piano* HIGDON Blue Cathedral SEP SEP DEBUSSY La Mer 21 22 CONNESSON The Shining One RAVEL Piano Concerto in G GERSHWIN An American in Paris Mahler’s Resurrection Stéphane Denève, conductor MAHLER Symphony No. 2, “Resurrection” Joélle Harvey, soprano SEP SEP Kelley O’Connor, alto St. Louis Symphony Chorus 27 28 Amy Kaiser, director OCT Rachmaninoff’s Third Piano Concerto Edo de Waart, conductor Joyce Yang, piano OCT OCT RACHMANINOFF Piano Concerto No. 3 4 5 ELGAR Symphony No. 1 A Hero’s Life Leonard Slatkin, conductor VARIOUS Yet Another Set of Variations (on a Theme of Paganini) Jelena Dirks, oboe OCT OCT MOZART Oboe Concerto, K. 314 12 13 R. STRAUSS Ein Heldenleben (A Hero’s Life) Symphonic Dances Stéphane Denève, conductor POULENC Les biches Suite Karen Gomyo, violin OCT OCT OCT PROKOFIEV Violin Concerto No. 1 18 19 20 RACHMANINOFF Symphonic Dances NOV Saint-Saëns’ Organ Symphony Stéphane Denève, conductor BARBER Adagio for Strings James Ehnes, violin NOV NOV J. WILLIAMS Violin Concerto 2 3 SAINT-SAËNS Symphony No. 3, “Organ” Mozart’s Great Mass Masaaki Suzuki, conductor HAYDN Symphony No. 48, “Maria Theresia” Mojca Erdmann, soprano MOZART Mass in C Minor, K. 427 Joanne Lunn, soprano Zachary Wilder, tenor NOV NOV Dashon Burton, bass-baritone 9 10 St. Louis Symphony Chorus Amy Kaiser, director Brahms’ Fourth Symphony Stéphane Denève, conductor KERNIS New Work (World Premiere) Gil Shaham, violin NOV NOV BARTÓK Violin Concerto No. -

Commencement Concert 2019

COMMENCEMENT CONCERT 2019 COMMENCEMENT CONCERT FRIDAY, JUNE 7, 2019 ▪ 7:30 P.M. LAWRENCE MEMORIAL CHAPEL Jeanette Adams ’19 Maggie Anderson ’19 Abbey Atwater ’19 Clover Austin-Muehleck ’19 Cosette Bardawil ’19 Julian Cohen ’19 Milou de Meij ’19 McKenzie Fetters ’19 Xiaoya Gao ’19 Luke Honeck ’19 Trace Hybertson ’19 Craig Jordan ’19 Abigail Keefe ’20 Bea McManus ’20 Aria Minasian ’19 Anna Mosoriak ’19 Maxim Muter ’21 Delaney Olsen ’19 Bianca Pratte ’20 Nicolette Puskar ’19 Alexander Quackenbush ’19 Emily Richter ’20 Nicholas Suminski ’20 Logan Willis ’20 Stuart Young ’19 Prelude in G Major, op. 32, no. 5, Sergei Rachmaninoff with an improvised cadenza (1873-1943) Milou de Meij (b. 1997) Milou de Meij, piano Suite, op. 157b Darius Milhaud III. Jeu (1892-1974) Abbey Atwater, clarinet McKenzie Fetters, violin In the Silent Night Rachmaninoff Aria Minasian, mezzo-soprano Nathan Birkholz, piano The Sounds Around Me Delaney Olsen (b. 1996) Delaney Olsen, oboe with fixed electronics Étude-Tableau, op. 33, no. 5 Rachmaninoff Craig Jordan, piano From Little Women Mark Adamo “Things Change, Jo” (b. 1962) Clover Austin-Muehleck, mezzo-soprano Nick Towns, piano Sonata, op. 94 Sergei Prokofiev IV. Allegro con brio (1891-1953) Abbey Atwater, clarinet Nick Towns, piano Lux Aeterna Logan Willis (b. 1998) Bianca Pratte, soprano Nicolette Puskar, soprano Emily Richter, soprano Bea McManus, mezzo-soprano Clover Austin-Muehleck, mezzo-soprano Luke Honeck, tenor Logan Willis, tenor Alexander Quackenbush, baritone Maxim Muter, bass-baritone INTERMISSION From The Tender Land Aaron Copland Laurie’s Song (1900-1990) Anna Mosoriak, soprano Linda Sparks, piano Whiskey Before Breakfast/April Blizzard Traditional arr. -

Paganini Variations

Thursday 28 February 2019 7.30–9.40pm Barbican Hall LSO SEASON CONCERT PAGANINI VARIATIONS Weill Symphony No 2 Rachmaninov LAHA Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini Interval Stravinsky Petrushka (1947 version) Lahav Shani conductor Simon Trpčeski piano HANI This performance is funded in part by the Kurt Weill Foundation for Music, Inc., New York, NY Welcome Latest News On our Blog We are grateful to the Kurt Weill Foundation A TRANSATLANTIC PARTNERSHIP RAVEL IN MADRID for Music for their generous support of tonight’s performance, and I would like to In January, the LSO welcomed a team of In 1923, on his first visit to Madrid, Maurice take this opportunity to thank our media young professional musicians – Keston MAX Ravel was hard at work on a piece of music partner Classic FM for recommending Fellows of Santa Barbara's Music Academy which his publishers urgently required. this concert to their listeners. We also of the West – who spent a week working Read more on our blog about Ravel’s welcome guests from the London Chamber alongside the Orchestra and taking part in Spanish influences and inspiration. of Commerce and Industry, a partner rehearsals, a mock recording session and organisation of the LSO. performing in LSO concerts at the Barbican. MEET LAHAV SHANI I hope that you enjoy the performance and CULTURE MILE COMMUNITY DAY Ahead of his LSO debut, we spoke to elcome to tonight’s LSO concert that you will be able to join us again soon. Lahav about Kurt Weill, musical life in at the Barbican for a programme In March we look forward to a trio of concerts On Sunday 17 February, LSO St Luke's Tel Aviv and what it’s like to step into of Stravinsky, Rachmaninov and celebrating Bernard Haitink’s 90th birthday was taken over for a day of performances, Zubin Mehta’s shoes as Music Director Kurt Weill. -

Jay Harvey Upstage

Jay Harvey Upstage Wednesday, September 5, 2018 The charm of the third time: IVCI preliminaries move toward their conclusion For me, the preliminary round of the International Violin Competition of Indianapolis ended Tuesday afternoon, though today there are nine more of the 38 participants to be heard. The jury's selection of 16 semifinalists is expected about 8 p.m. today. Like the rest of the public, I have the option to take advantage of live-streaming for the remaining prelim recitals. I might check out some of them, but of course there's no substitute for being there. That was driven home to me by the last recital of the day Sept. 4. The live-streaming experience can provide an excellent perspective on the participants, but I might have missed what stood out most Tuesday afternoon if I'd taken in remotely the prelim recital of Galiya Zharova of Kazakhstan. In the course of her performance, I almost put aside "large- picture" artistic considerations. They seemed to be well-served in any case by her exemplary bow control. And that's what I focused on. Her bow arm was beautiful to watch, note after note. I could have admired its steadiness and consistency for longer in another piece of music beyond the scheduled program. Maybe IVCI patrons will get to see for themselves in the semifinals. It took a while for it to dawn on me. In retrospect, the oft-heard Adagio from Bach's Sonata No. 1 in G minor presented an interpretation that only bowing under precise coordination could have managed: The melodic line was sustained and soaring, while the harmonic underpinning was never scanted in the slightest. -

2020-2021-Baritone-Solo-List-1.Pdf

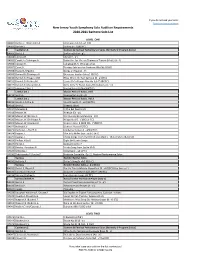

If you do not see your solo: Solo level request form New Jersey Youth Symphony Solo Audition Requirements 2020-2021 Baritone Solo List LEVEL ONE 04001 Berlioz,H./Ostrander,A. Unknown Isle (d - g') (TC) 04002 Buchtel,F. Bolero (c - f')(BCfrC) Castleton,G. Contest & Festival Performance Solos (formerly 9 Program Solos) 04003 Bach,J.S. Sinfonia (b flat - g') 04004 Clerisse,R. Idylle (A - e') 04005 Corelli,A./Dishinger,R. Suite Var. for Vln. on Themes of Tartini (Mvt.l) (d - f') 04006 Corwell,N. Lullabye (G-f') (This ed. only) 04007 Court,D. Fantasy Jubiloso for Baritone (Bb-Eb) (BCffC) 04008 Faure,G./Mead,S. Apres un Reve (c - f') 04009 Godard,B./Dishinger,R. Berceuse Jocelyn (eb-g') (BCffC) 04010 Handel,G./Fitzgerald,B. Thus When the Sun Samson (d - g') (TC) 04011 Handel,G./Forbes,M. Lascia Ch'io Pianga Rinaldo (eb-f') (BCffC) 04012 Handel,G./Ostrander,A. Arm, Arm, Ye Brave Judas Maccabaeus (c - e') 04013 Johnson,C.(arr.) Sacred Solos (Either)(BCfTC) Lamb,J.(cd.) Classic Festival Solos, Vol.l 04014 Smith,L. Concentration (B - g') Lamb,J.(cd.) Classic Festival Solos, Vol.2 04015 Haydn,J./Little,D. Divertimento (F - eb')(BCffC) 04016 Smith,L. Cheerio (Bb-f) 04017 Marcello,B. Il Mio Bel Foco (c-g') 04018 Mozart,W. Alleluja (Eb - g') 04019 Mozart,W./Barncs,C. Per Questa Bella Mano (G - cb') 04020 Mozart,W./Dishinger,R. Allegretto (G - c')(BC/or TC) 04021 Mozart,W./Voxman,H. Concert Aria, K.382h (Bb - f')(BCffC) 04022 Nelhybel,V. Concert Piece (BCfTC) 04023 Pachabel,J./Dorff,D. -

The Merry Widow November 2007 the Merry Widow

The Merry Widow November 2007 The Merry Widow Music by Franz Lehár Produced by kind permission of the Australian Ballet Foundation Original book and lyrics by Victor Leon and Leo Stein Choreography: Ronald Hynd Scenario: Sir Robert Helpmann Music: Franz Lehár Musical Adaptation: John Lanchbery Set and Costume Design: Desmond Heeley Lighting Design: Michael J. Whitfield This production entered the repertoire through the generosity of THE VOLUNTEER COMMITTEE, THE NATIONAL BALLET OF CANADA, joined by the Rotary Club of Toronto. This balletic version, choreography by Ronald Hynd and scenario by Sir Robert Helpmann, has been made courtesy of the composer’s and librettists’ heirs and by special arrangement with Glocken Verlag Limited, London. The Merry Widow is presented by Cover: Greta Hodgkinson as Hanna (2001). Right: Karen Kain and John Meehan as Hanna and Danilo in the National Ballet premiere (1986). The Merry Widow The year is 1905 and the fate of the proud but impoverished Balkan principality of Pontevedro hangs perilously on the marriage plans of a rich, beautiful widow. If she weds a foreigner it could spell financial ruin for her homeland, therefore she must be coaxed into marrying a fellow Pontevedrian. The Merry Widow first delighted audiences as an operetta and has continued to do so as a ballet. Hungarian composer Franz Lehár’s The Merry Widow was first presented in Vienna in 1905. A musical feast, it aptly captures the contrasting national passions of the Balkan Pontevedrians and the elegant Parisians whose city is the backdrop for this story of love and intrigue. Artists of the Ballet (1997). -

Chapter 17: Romantic Spectacles: from Virtuosos to Grand Opera: 1800–1850

Chapter 17: Romantic Spectacles: From Virtuosos to Grand Opera: 1800–1850 I. Romantic spectacles A. Introduction 1. Spectacle became an important means of drawing audiences to public concerts and operas. 2. French opera of the time became known as grand opéra because of its sensational musical and visual effects. 3. The size of audiences grew rapidly in the nineteenth century in response to new economic, demographic, and technological developments. II. The devil’s violinist: Niccolò Paganini A. Paganini was the first in a line of nineteenth-century virtuoso performers who toured European concert halls. B. His virtuoso playing set high standards, which were also demonstrated in his publications. C. While Schubert likened his playing to the song of an angel, most associated Paganini’s talent with a deal with the devil. 1. Legends grew around Paganini and sorcery. D. Paganini’s performance in Paris in 1831 inspired Liszt to become the “Paganini of the Piano.” E. Despite a short major performing career, Paganini’s impact was formidable. F. The technical demands of Paganini’s shorter works (particularly the caprices) caused them to be deemed “unplayable.” 1. Left-hand pizzicato, octaves, etc. III. “The Paganini of the Piano”: Franz Liszt A. Liszt was born in an area that mixed Hungarian and German culture. 1. He spoke German but at times styled himself as an exotic Hungarian. B. As a boy, he studied piano with Czerny (Beethoven’s pupil) and composition with Salieri. 1. He was acknowledged as a prodigy by Czerny. 2. He debuted in Paris in 1824 (he was born in 1811).