KEITH JARRETT & ALL THAT JAZZ by Eric

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Discourses of Decay and Purity in a Globalised Jazz World

1 Chapter Seven Cold Commodities: Discourses of Decay and Purity in a Globalised Jazz World Haftor Medbøe Since gaining prominence in public consciousness as a distinct genre in early 20th Century USA, jazz has become a music of global reach (Atkins, 2003). Coinciding with emerging mass dissemination technologies of the period, jazz spread throughout Europe and beyond via gramophone recordings, radio broadcasts and the Hollywood film industry. America’s involvement in the two World Wars, and the subsequent $13 billion Marshall Plan to rebuild Europe as a unified, and US friendly, trading zone further reinforced the proliferation of the new genre (McGregor, 2016; Paterson et al., 2013). The imposition of US trade and cultural products posed formidable challenges to the European identities, rooted as they were in 18th-Century national romanticism. Commercialised cultural representations of the ‘American dream’ captured the imaginations of Europe’s youth and represented a welcome antidote to post-war austerity. This chapter seeks to problematise the historiography and contemporary representations of jazz in the Nordic region, with particular focus on the production and reception of jazz from Norway. Accepted histories of jazz in Europe point to a period of adulatory imitation of American masters, leading to one of cultural awakening in which jazz was reimagined through a localised lens, and given a ‘national voice’. Evidence of this process of acculturation and reimagining is arguably nowhere more evident than in the canon of what has come to be received as the Nordic tone. In the early 1970s, a group of Norwegian musicians, including saxophonist Jan Garbarek (b.1947), guitarist Terje Rypdal (b.1947), bassist Arild Andersen (b.1945), drummer Jon Christensen (b.1943) and others, abstracted more literal jazz inflected reinterpretations of Scandinavian folk songs by Nordic forebears including pianist Jan Johansson (1931-1968), saxophonist Lars Gullin (1928-1976) bassist Georg Riedel (b.1934) (McEachrane 2014, pp. -

Why Jazz Still Matters Jazz Still Matters Why Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences Journal of the American Academy

Dædalus Spring 2019 Why Jazz Still Matters Spring 2019 Why Dædalus Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences Spring 2019 Why Jazz Still Matters Gerald Early & Ingrid Monson, guest editors with Farah Jasmine Griffin Gabriel Solis · Christopher J. Wells Kelsey A. K. Klotz · Judith Tick Krin Gabbard · Carol A. Muller Dædalus Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences “Why Jazz Still Matters” Volume 148, Number 2; Spring 2019 Gerald Early & Ingrid Monson, Guest Editors Phyllis S. Bendell, Managing Editor and Director of Publications Peter Walton, Associate Editor Heather M. Struntz, Assistant Editor Committee on Studies and Publications John Mark Hansen, Chair; Rosina Bierbaum, Johanna Drucker, Gerald Early, Carol Gluck, Linda Greenhouse, John Hildebrand, Philip Khoury, Arthur Kleinman, Sara Lawrence-Lightfoot, Alan I. Leshner, Rose McDermott, Michael S. McPherson, Frances McCall Rosenbluth, Scott D. Sagan, Nancy C. Andrews (ex officio), David W. Oxtoby (ex officio), Diane P. Wood (ex officio) Inside front cover: Pianist Geri Allen. Photograph by Arne Reimer, provided by Ora Harris. © by Ross Clayton Productions. Contents 5 Why Jazz Still Matters Gerald Early & Ingrid Monson 13 Following Geri’s Lead Farah Jasmine Griffin 23 Soul, Afrofuturism & the Timeliness of Contemporary Jazz Fusions Gabriel Solis 36 “You Can’t Dance to It”: Jazz Music and Its Choreographies of Listening Christopher J. Wells 52 Dave Brubeck’s Southern Strategy Kelsey A. K. Klotz 67 Keith Jarrett, Miscegenation & the Rise of the European Sensibility in Jazz in the 1970s Gerald Early 83 Ella Fitzgerald & “I Can’t Stop Loving You,” Berlin 1968: Paying Homage to & Signifying on Soul Music Judith Tick 92 La La Land Is a Hit, but Is It Good for Jazz? Krin Gabbard 104 Yusef Lateef’s Autophysiopsychic Quest Ingrid Monson 115 Why Jazz? South Africa 2019 Carol A. -

Hybridity and Identity in the Pan-American Jazz Piano Tradition

Hybridity and Identity in the Pan-American Jazz Piano Tradition by William D. Scott Bachelor of Arts, Central Michigan University, 2011 Master of Music, University of Michigan, 2013 Master of Arts, University of Michigan, 2015 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2019 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by William D. Scott It was defended on March 28, 2019 and approved by Mark A. Clague, PhD, Department of Music James P. Cassaro, MA, Department of Music Aaron J. Johnson, PhD, Department of Music Dissertation Advisor: Michael C. Heller, PhD, Department of Music ii Copyright © by William D. Scott 2019 iii Michael C. Heller, PhD Hybridity and Identity in the Pan-American Jazz Piano Tradition William D. Scott, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2019 The term Latin jazz has often been employed by record labels, critics, and musicians alike to denote idioms ranging from Afro-Cuban music, to Brazilian samba and bossa nova, and more broadly to Latin American fusions with jazz. While many of these genres have coexisted under the Latin jazz heading in one manifestation or another, Panamanian pianist Danilo Pérez uses the expression “Pan-American jazz” to account for both the Afro-Cuban jazz tradition and non-Cuban Latin American fusions with jazz. Throughout this dissertation, I unpack the notion of Pan-American jazz from a variety of theoretical perspectives including Latinx identity discourse, transcription and musical analysis, and hybridity theory. -

Carnegie Hall a Rn Eg Ie an D H Is W Ife Lo 12 Then and Now Uise, 19

A n d r e w C Carnegie Hall a rn eg ie an d h is w ife Lo 12 Then and Now uise, 19 Introduction The story of Carnegie Hall begins in the middle of the Atlantic. itself with the history of our country.” Indeed, some of the most In the spring of 1887, on board a ship traveling from New York prominent political figures, authors, and intellectuals have to London, newlyweds Andrew Carnegie (the ridiculously rich appeared at Carnegie Hall, from Woodrow Wilson and Theodore industrialist) and Louise Whitfield (daughter of a well-to-do New Roosevelt to Mark Twain and Booker T. Washington. In addition to York merchant) were on their way to the groom’s native Scotland standing as the pinnacle of musical achievement, Carnegie Hall has for their honeymoon. Also on board was the 25-year-old Walter been an integral player in the development of American history. Damrosch, who had just finished his second season as conductor and musical director of the Symphony Society of New York and ••• the Oratorio Society of New York, and was traveling to Europe for a summer of study with Hans von Bülow. Over the course of After he returned to the US from his honeymoon, Carnegie set in the voyage, the couple developed a friendship with Damrosch, motion his plan, which he started formulating during his time with inviting him to visit them in Scotland. It was there, at an estate Damrosch in Scotland, for a new concert hall. He established The called Kilgraston, that Damrosch discussed his vision for a new Music Hall Company of New York, Ltd., acquired parcels of land concert hall in New York City. -

Stylistic Evolution of Jazz Drummer Ed Blackwell: the Cultural Intersection of New Orleans and West Africa

STYLISTIC EVOLUTION OF JAZZ DRUMMER ED BLACKWELL: THE CULTURAL INTERSECTION OF NEW ORLEANS AND WEST AFRICA David J. Schmalenberger Research Project submitted to the College of Creative Arts at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Percussion/World Music Philip Faini, Chair Russell Dean, Ph.D. David Taddie, Ph.D. Christopher Wilkinson, Ph.D. Paschal Younge, Ed.D. Division of Music Morgantown, West Virginia 2000 Keywords: Jazz, Drumset, Blackwell, New Orleans Copyright 2000 David J. Schmalenberger ABSTRACT Stylistic Evolution of Jazz Drummer Ed Blackwell: The Cultural Intersection of New Orleans and West Africa David J. Schmalenberger The two primary functions of a jazz drummer are to maintain a consistent pulse and to support the soloists within the musical group. Throughout the twentieth century, jazz drummers have found creative ways to fulfill or challenge these roles. In the case of Bebop, for example, pioneers Kenny Clarke and Max Roach forged a new drumming style in the 1940’s that was markedly more independent technically, as well as more lyrical in both time-keeping and soloing. The stylistic innovations of Clarke and Roach also helped foster a new attitude: the acceptance of drummers as thoughtful, sensitive musical artists. These developments paved the way for the next generation of jazz drummers, one that would further challenge conventional musical roles in the post-Hard Bop era. One of Max Roach’s most faithful disciples was the New Orleans-born drummer Edward Joseph “Boogie” Blackwell (1929-1992). Ed Blackwell’s playing style at the beginning of his career in the late 1940’s was predominantly influenced by Bebop and the drumming vocabulary of Max Roach. -

Pat Metheny 80/81 Mp3, Flac, Wma

Pat Metheny 80/81 mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Jazz Album: 80/81 Country: Japan Released: 1980 Style: Post Bop, Contemporary Jazz MP3 version RAR size: 1322 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1569 mb WMA version RAR size: 1314 mb Rating: 4.4 Votes: 404 Other Formats: AU RA MP1 MIDI AHX MOD MMF Tracklist Hide Credits Two Folk Songs 1st 1 13:17 Composed By – Pat Metheny 2nd 2 7:31 Composed By – Charlie Haden - 80/81 3 7:28 Composed By – Pat Metheny The Bat 4 5:58 Composed By – Pat Metheny Turnaround 5 7:05 Composed By – Ornette Coleman Open 6 Composed By – Haden*, Redman*, DeJohnette*, Brecker*, Metheny*Composed 14:25 By [Final Theme] – Pat Metheny Pretty Scattered 7 6:56 Composed By – Pat Metheny Every Day (I Thank You) 8 13:16 Composed By – Pat Metheny Goin' Ahead 9 3:56 Composed By – Pat Metheny Companies, etc. Recorded At – Talent Studio Lacquer Cut At – PRS Hannover Credits Bass – Charlie Haden Design – Barbara Wojirsch Drums – Jack DeJohnette Engineer – Jan Erik Kongshaug Guitar – Pat Metheny Photography By [Back] – Dag Alveng Photography By [Inside] – Rainer Drechsler Producer – Manfred Eicher Tenor Saxophone – Dewey Redman (tracks: B1, B2, C1, C2), Mike Brecker* (tracks: A1, A2, B2, C1, C2, D1) Notes Recorded May 26-29, 1980 at Talent Studios, Oslo. An ECM Production. ℗ 1980 ECM Records GmbH. Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode: 042281557941 Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year ECM 1180/81, 80/81 (2xLP, ECM Records, ECM 1180/81, Pat Metheny Germany 1980 2641 180 Album) ECM Records -

The Dölerud Johansson Quintet

Dölerud Johansson Quintet Magnus Dölerud and Dan Johansson formed their quintet in 2016, bringing together some of Sweden’s most accomplished musicians. The members – Dan, Magnus, Torbjörn Gulz, Palle Danielsson and Fredrik Rundqvist – had previously crossed paths in other constellations, but this collaboration has resulted in something truly extra special. The quintet’s collective experience spans a long list of Swedish and International associations, from Keith Jarrett’s legendary European Quartet via the Fredrik Norén Band, which has spawned the careers of so many Swedish musicians over its 32- year history to the Norbotten Big Band, one of the most important jazz institutions in Sweden today, with collaborators like: Tim Hagans, Maria Schnieder, Joe Lovano, Bob Brookmeyer and Kurt Rosenwinkel. The quintet brings music to the stage that reflects that history, combining jazz tradition with the members’ own compositions. During 2017 and 2018, the band toured jazz clubs and festivals in Sweden and Finland, to warm receptions from audiences and reviewers alike. In May 2018, they recorded their first album, Echoes & Sounds, to be released this autumn. Dan Johansson Dan Johansson plays trumpet and flugelhorn in the Norbotten Big Band and is a well-established musician who has – in a career that extends over 30 years -- played with both the Swedish and International jazz elite. He became a member of the Norbotten Big Band while still a student and has played with the band since 1986. There he’s had the privilege to perform with figures like Randy Brecker, Peter Erskine, Joey Calderazzo, Jeff “Tain” Watts and Bob Berg. On top of his work with the big band, he’s played in a wide variety of smaller groups that have included: Håkan Broström. -

Jazz Standards Arranged for Classical Guitar in the Style of Art Tatum

JAZZ STANDARDS ARRANGED FOR CLASSICAL GUITAR IN THE STYLE OF ART TATUM by Stephen S. Brew Submitted to the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree, Doctor of Music Indiana University May 2018 Accepted by the faculty of the Indiana University Jacobs School of Music, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Music Doctoral Committee ______________________________________ Luke Gillespie, Research Director ______________________________________ Ernesto Bitetti, Chair ______________________________________ Andrew Mead ______________________________________ Elzbieta Szmyt February 20, 2018 ii Copyright © 2018 Stephen S. Brew iii To my wife, Rachel And my parents, Steve and Marge iv Acknowledgements This document would not have been possible without the guidance and mentorship of many creative, intelligent, and thoughtful musicians. Maestro Bitetti, your wisdom has given me the confidence and understanding to embrace this ambitious project. It would not have been possible without you. Dr. Strand, you are an incredible mentor who has made me a better teacher, performer, and person; thank you! Thank you to Luke Gillespie, Elzbieta Szmyt, and Andrew Mead for your support throughout my coursework at IU, and for serving on my research committee. Your insight has been invaluable. Thank you to Heather Perry and the staff at Stonehill College’s MacPhaidin Library for doggedly tracking down resources. Thank you James Piorkowski for your mentorship and encouragement, and Ken Meyer for challenging me to reach new heights. Your teaching and artistry inspire me daily. To my parents, Steve and Marge, I cannot express enough thanks for your love and support. And to my sisters, Lisa, Karen, Steph, and Amanda, thank you. -

Biography of Lars Danielsson

Biography of Lars Danielsson The late great Danish bass legend Nils-Henning Ǿrsted Pedersen didn't only leave the world a direct legacy of great jazz through his own playing; a part of what he has bequeathed is indirect. When the young Swedish musician Lars Danielsson once heard him in concert, he was so deeply affected, he turned towards jazz, and to the bass. Until that point, Danielsson, born in Gothenburg in 1958, had been studying classical cello at the conservatory in his home town of Gothenburg. Fortunately, that study of the cello is not something he has chosen to shrug off, he has integrated it into what he does now. Not just in the sense that he always includes the cello in his repertoire, but also that his bass-playing unmistakably has a slightly more melodious, floating and lyrical ring to it than that of many of his fellow bass players. These were the special qualities which soon placed him in very high demand internationally as a sideman. As early as the 1980s, he had worked not only with local and European greats such as Lars Jansson, Hans Ulrik, Carsten Dahl, Nils Landgren, Christopher Dell, Johannes Enders and Trilok Gurtu (in whose group he remained a member for some time), but also with luminaries of the American scene such as saxophonists Rick Margitza and Charles Lloyd, the Brecker Brothers, drummers Terri Lyne Carrington , Jack DeJohnette and Billy Hart or guitarists John Scofield, Mike Stern and John Abercrombie. But Danielsson has never been content with just an accompanying role. He has always been a creative composer as well and is one of a relatively small group of bassists who has also emerged as a significant bandleader. -

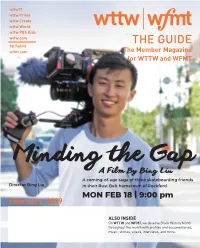

Inside the Guide the Guide

wttw11 wttw Prime wttw Create wttw World wttw PBS Kids wttw.com THE GUIDE 98.7wfmt wfmt.com The Member Magazine for WTTW and WFMT A coming-of-age saga of three skateboarding friends Director Bing Liu in their Rust Belt hometown of Rockford. MON FEB 18 | 9:00 pm February 2019 ALSO INSIDE On WTTW and WFMT, we observe Black History Month throughout the month with profiles and documentaries, music, stories, videos, interviews, and more. From the President & CEO The Guide The Member Magazine for WTTW and WFMT Dear Member, Renée Crown Public Media Center 5400 North Saint Louis Avenue Greetings from WTTW and WFMT. This month, we are excited to bring you Chicago, Illinois 60625 the acclaimed documentary about the life of a public media treasure and icon – Mister Fred Rogers. Won’t You Be My Neighbor? premieres on WTTW11 on Main Switchboard (773) 583-5000 February 9. Join us for an in-depth and entertaining look at the life of a visionary Member and Viewer Services who fostered compassion and curiosity in generations of children and families. (773) 509-1111 x 6 February is also Black History Month, and we will celebrate it on WTTW11, Websites WTTW Prime, and wttw.com. You’ll find highlights of this special programming wttw.com on page 7 and at wttw.com/blackhistorymonth. Don’t miss new Finding Your wfmt.com Roots specials, in which Dr. Henry Louis Gates, Jr. explores race, family, and Publisher identity in today’s America by uncovering the genealogy of Michael Strahan, Anne Gleason S. Epatha Merkerson, and many more. -

Norway's Jazz Identity by © 2019 Ashley Hirt MA

Mountain Sound: Norway’s Jazz Identity By © 2019 Ashley Hirt M.A., University of Idaho, 2011 B.A., Pittsburg State University, 2009 Submitted to the graduate degree program in Musicology and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, Musicology. __________________________ Chair: Dr. Roberta Freund Schwartz __________________________ Dr. Bryan Haaheim __________________________ Dr. Paul Laird __________________________ Dr. Sherrie Tucker __________________________ Dr. Ketty Wong-Cruz The dissertation committee for Ashley Hirt certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: _____________________________ Chair: Date approved: ii Abstract Jazz musicians in Norway have cultivated a distinctive sound, driven by timbral markers and visual album aesthetics that are associated with the cold mountain valleys and fjords of their home country. This jazz dialect was developed in the decade following the Nazi occupation of Norway, when Norwegians utilized jazz as a subtle tool of resistance to Nazi cultural policies. This dialect was further enriched through the Scandinavian residencies of African American free jazz pioneers Don Cherry, Ornette Coleman, and George Russell, who tutored Norwegian saxophonist Jan Garbarek. Garbarek is credited with codifying the “Nordic sound” in the 1960s and ‘70s through his improvisations on numerous albums released on the ECM label. Throughout this document I will define, describe, and contextualize this sound concept. Today, the Nordic sound is embraced by Norwegian musicians and cultural institutions alike, and has come to form a significant component of modern Norwegian artistic identity. This document explores these dynamics and how they all contribute to a Norwegian jazz scene that continues to grow and flourish, expressing this jazz identity in a world marked by increasing globalization. -

Keith Jarrett's Spiritual Beliefs Through a Gurdjieffian Lens

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by The University of Sydney: Sydney eScholarship Journals... Channelling the Creative: Keith Jarrett’s Spiritual Beliefs Through a Gurdjieffian Lens Johanna Petsche Introduction The elusive nature of the creative process in art has remained a puzzling phenomenon for artists and their audiences. What happens to an inspired artist in the moment of creation and where that inspiration comes from are questions that prompt many artists to explain the process as spiritual or mystical, describing their experiences as ‘channelling the divine’, ‘tapping into a greater reality’, or being visited or played by their ‘muse’. Pianist and improviser Keith Jarrett (b.1945) frequently explains the creative process in this way and this is nowhere more evident than in discussions on his wholly improvised solo concerts. Jarrett explains these massive feats of creativity in terms of an ability to ‘channel’ or ‘surrender to’ a source of inspiration, which he ambiguously designates the ‘ongoing harmony’, the ‘Creative’, and the ‘Divine Will’. These accounts are freely expressed in interviews and album liner notes, and are thus highly accessible to his audiences. Jarrett’s mystical accounts of the creative process, his incredible improvisatory abilities, and other key elements come together to create the strange aura of mystery that surrounds his notorious solo concerts. This paper will demystify Jarrett’s spiritual beliefs on the creative process by considering them within a Gurdjieffian context. This will allow for a much deeper understanding of Jarrett’s cryptic statements on creativity, and his idiosyncratic behaviour during the solo concerts.