Swara-The Human Shield

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CASSA Annual Report 2016

COUNCIL OF AGENCIES SERVING SOUTH ASIANS (CASSA) CASSA Annual Report 2016 CASSA Annual General Meeting 2016 COUNCIL OF AGENCIES SERVING SOUTH ASIANS (CASSA) Annual General Meeting Thursday, August 11th, 2016 Friends House 60 Lowther Ave, Toronto, M5R 1C7 5200 Finch Ave. E., Suite 301A, Scarborough M1S 4Z5 Tel. No: (416) 932 1359 Fax No: (416) 932 9305 Email: [email protected] 2 CASSA Annual General Meeting 2016 Agenda Council of Agencies Serving South Asians (CASSA) Annual General Meeting August11th, 2016 Friends House 5:30pm – 6:00pm Registration, Networking and Refreshments 6:00pm – 6:45pm Welcome To Annual General Meeting Approval of Draft Agenda Approval of last AGM Minutes President’s and Executive Director’s Report Approval of Auditor’s Report – Appointment of Auditor Nomination Report and Election of New Board Members Adjournment of Business 6:45pm – 7:05pm Volunteer and Board Appreciation 7:05pm – 7:45pm Panel Discussion • Saira Ansari, Diversity & Inclusion Manager (Earth Day Canada) • Linda Koehler, Community Recreation Supervisor (Parks & Recreation – City of Toronto) • Parul Pandya, Community Engagement & Communications Manager (Toronto Arts Foundation) 7:45pm – 8:00pm Q&A Session 8:00pm – 8:30pm Dinner and Networking 3 CASSA Annual General Meeting 2016 AGM Minutes of CASSA - June 17th 2015 at Friends House, Toronto The meeting was called to order by Mohan Swaminathan, Chair of the Board. The motion to approve the agenda was made by Jawad Bhatti and seconded by Qasir Sheikh. Anu Sharma made the motion to approve the previous AGM minutes, seconded by Shaji John. President’s Report Mohan presented the President’s report. -

A Linguistic Critique of Pakistani-American Fiction

CULTURAL AND IDEOLOGICAL REPRESENTATIONS THROUGH PAKISTANIZATION OF ENGLISH: A LINGUISTIC CRITIQUE OF PAKISTANI-AMERICAN FICTION By Supervisor Muhammad Sheeraz Dr. Muhammad Safeer Awan 47-FLL/PHDENG/F10 Assistant Professor A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English To DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH FACULTY OF LANGUAGES AND LITERATURE INTERNATIONAL ISLAMIC UNIVERSITY ISLAMABAD April 2014 ii iii iv To my Ama & Abba (who dream and pray; I live) v ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I owe special gratitude to my teacher and research supervisor, Dr. Muhammad Safeer Awan. His spirit of adventure in research, the originality of his ideas in regard to analysis, and the substance of his intellect in teaching have guided, inspired and helped me throughout this project. Special thanks are due to Dr. Kira Hall for having mentored my research works since 2008, particularly for her guidance during my research at Colorado University at Boulder. I express my deepest appreciation to Mr. Raza Ali Hasan, the warmth of whose company made my stay in Boulder very productive and a memorable one. I would also like to thank Dr. Munawar Iqbal Ahmad Gondal, Chairman Department of English, and Dean FLL, IIUI, for his persistent support all these years. I am very grateful to my honorable teachers Dr. Raja Naseem Akhter and Dr. Ayaz Afsar, and colleague friends Mr. Shahbaz Malik, Mr. Muhammad Hussain, Mr. Muhammad Ali, and Mr. Rizwan Aftab. I am thankful to my friends Dr. Abdul Aziz Sahir, Dr. Abdullah Jan Abid, Mr. Muhammad Awais Bin Wasi, Mr. Muhammad Ilyas Chishti, Mr. Shahid Abbas and Mr. -

Faizghar Newsletter

Issue: January Year: 2016 NEWSLETTER Content Faiz Ghar trip to Rana Luxury Resort .............................................. 3 Faiz International Festival ................................................................... 4 Children at FIF ............................................................................................. 11 Comments .................................................................................................... 13 Workshop on Thinking Skills ................................................................. 14 Capacity Building Training workshops at Faiz Ghar .................... 15 [Faiz Ghar Music Class tribute to Rasheed Attre .......................... 16 Faiz Ghar trip to [Rana Luxury Resort The Faiz Ghar yoga class visited the Rana Luxury Resort and Safari Park at Head Balloki on Sunday, 13th December, 2015. The trip started with live music on the tour bus by the Faiz Ghar music class. On reaching the venue, the group found a quiet spot and spread their yoga mats to attend a vigorous yoga session conducted by Yogi Sham- shad Haider. By the time the session ended, the cold had disappeared, and many had taken o their woollies. The time was ripe for a fruit eating session. The more sporty among the group started playing football and frisbee. By this time the musicians had got their act together. The live music and dance session that followed became livelier when a large group of school girls and their teachers joined in. After a lot of food for the soul, the group was ready to attack Gogay kay Chaney, home made koftas, organic salads, and the most delicious rabri kheer. The group then took a tour of the jungle and the safari park. They enjoyed the wonderful ambience of the bamboo jungle, and the ostriches, deers, parakeet, swans, and many other wild animals and birds. Some members also took rides on the train and colour- ful donkey carts. -

Name CNIC Date of Birth (Dd/Mm/Yyyy) Amount Submission

LIST OF CATEGORY -III MEMBERS REGISTERED IN MEMBERSHIP DRIVE-II(Part-4th) Date of Birth Name CNIC Amount Submission Date (dd/mm/yyyy) A SATTAR UMERANI 4200036095311 1-Feb-70 25000 25-Mar-19 Aaber Farooq 33301-4817637-3 03/09/1986 25,000 25-Mar-19 Aabis Raza Kazmi 34101-7982643-3 14/9/1990 25,000 6-Mar-19 Aamir Ali 31101-3366151-7 9/9/1991 25,000 21-Mar-19 AAMIR SHAHZAD 3310007107175 25-Sep-72 25000 21-Mar-19 AASHIQ ALI MEMON 4330329942951 21-Aug-69 25000 22-Mar-19 AASIM BASHIR 3740567745419 20-Oct-70 25000 11-Mar-19 Abaid Ullah 32103-2518976-5 1/6/1966 25,000 25-Mar-19 ABDUL ALEEM KHAN 3520230658047 9-Mar-65 25000 25-Mar-19 ABDUL AZEEM JATOI 4230177451543 1-Apr-78 25000 25-Mar-19 ABDUL AZIZ 6110142134913 1-May-64 25000 22-Mar-19 Abdul Bari 32402-5221299-9 10/9/1965 25,000 25-Mar-19 ABDUL BASIT 3740540476955 24-Mar-88 25000 21-Mar-19 ABDUL GHAFFAR 3550102289413 1-Apr-89 25000 25-Mar-19 ABDUL GHAFFAR 5210105714535 17-Jul-80 25000 14-Mar-19 ABDUL GHAFFAR 4220102855149 4-Mar-60 25000 14-Mar-19 ABDUL GHAFFFAR KHAN 8210299699793 18-Dec-71 25000 25-Mar-19 ABDUL GHAFOOR 4230109573757 6-Mar-75 25000 25-Mar-19 Date of Birth Name CNIC Amount Submission Date (dd/mm/yyyy) ABDUL GHAFOOR 3740615687037 22-Oct-63 25000 22-Mar-19 ABDUL GHAFOOR SANJRANI 4230103641849 30-May-57 25000 18-Mar-19 ABDUL HAFEEZ 4130381796287 2-Mar-85 25000 18-Mar-19 Abdul Hameed 35202-5798517-7 13/11/1951 25,000 13-Mar-19 ABDUL HAMEED 4240116994783 20-Sep-62 25000 25-Mar-19 ABDUL HAMID 4210178803863 12-Mar-63 25000 22-Mar-19 ABDUL HAMID KHAN 4210115977797 12-Jan-64 25000 25-Mar-19 -

Pakistan's National Conservation Strategy

PAKISTAN’S NATIONAL CONSERVATION STRATEGY: RENEWING COMMITMENT TO ACTION Report of the Mid-Term Review by Arthur J. Hanson Stephen Bass Aziz Bouzaher Ghulam M. Samdani with the assistance of Maheen Zehra November 2000 ABOUT THIS REPORT This report was prepared by the External Review Team (ERT) and is based on findings of the Team, including other results from the Pakistan National Conservation Strategy Mid-term Review (MTR). The main period of work took place during 1999-2000. Comments were received between July-November 2000. This final version was completed in November 2000. 1 Pakistan’s National Conservation Strategy: Renewing Commitment to Action EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1. Background This report is the culmination of a one-year effort to undertake a Mid-term Review (MTR) of the achievements, impacts and prospects of Pakistan’s National Conservation Strategy (NCS) since the beginning of its implementation in 1992. The report was prepared by an independent review team, based on materials and information developed through an intensive consultation and review process coordinated by the Government of Pakistan. The information gathered includes studies, various background documentation, plus the results of consultative meetings held throughout Pakistan and involving government, civil society, the private sector and international donor agencies. The key studies are available as separate reports. Irrespective of the considerable methodological challenges attending the task of reviewing the outcomes of such a wide-ranging initiative as the NCS, with its 14 major objectives and some 68 programs, plus related local initiatives including provincial conservation strategies, the authors are confident that the overall conclusions and recommendations of this report will provide a strong basis for achieving enhanced outcomes during the next phase of the NCS. -

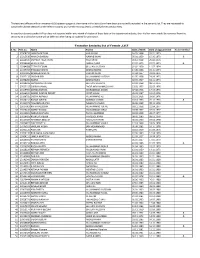

Tentative Seniority List of Teaching Faculty Working in J&K Govt

Tentative Seniority list of Teaching faculty working in Jammu and Kashmir Government Colleges. As on 1-07-2017. Date of placement Date of Present place of S.No Name Category Qualification Subject DOB appointment AGP 7000/- ABP 8000/- AGP 9000/- posting 1 Nighat Wani Home Sc. 15.Mar.1959 18.Aug.1980 2 Nirmal Narayan M.Sc/B.Ed Geography 10.Jun.1961 4.Mar.1983 GDC Kathua 3 Shagufta Yasvi Ph.D Chemistry 21.Mar.1959 14.Mar.1983 4 Sudha Gupta Open M. Sc Home.Sc 23.Mar.1958 29.Jun.1983 01.01.2006 WC Gandhinagar 5 Yudvir Singh Ph. D Commerce 20.Apr.1958 15.Jul.1983 RUSA 6 Zahir-Ud-Din M.Com Commerce 18.Oct.1958 16.Jul.1983 7 Neeru Balla Open M.Com Commerce 15.Oct.1960 16.Jul.1983 01.01.1996 27.07.1998 01.01.2006 SPMR College 8 Bushra Shamin M.Com Commerce 21.Mar.1959 16.Jul.1983 9 Kiran Kumari Open M.Com Commerce 1.May.1960 16.Jul.1983 01.01.1996 27.07.1998 01.01.2006 SPMR College 10 Suman Bala M.Com Commerce 17.Mar.1959 16.Jul.1983 11 Rakesh Gupta Open Ph. D Commerce 16.Nov.1958 16.Jul.1983 01.08.1991 01.08.1996 01.01.2006 MAM College 12 Ab. Roaf M. Phil Commerce 8.Jan.1961 16.Jul.1983 claim for Sr. 2 13 Rifat Geelani M.A. Arabic 8.Apr.1960 29.Sep.1983 14 Abdul Hai Ph.d. Zoology 13.Oct.1961 16.Jun.1984 26-Jun-1992 27-Jul-1998 1-Jan-2006 Amar Singh College 15 Nasreen Malik M.Phil Zoology 26.Mar.1958 16.Jun.1984 16 Kartar Chand SC M.Sc. -

Yoga in Gita Remembering Malika Pukhraj Lt Col R K Langar Action Is Favorable Or Unfavorable Towards Attainable by Unswerving Devotion

SUNDAY, DECEMBER 22, 2013 (PAGE-3) SACRED SPACE TRIBUTE Yoga in Gita Remembering Malika Pukhraj Lt Col R K Langar action is favorable or unfavorable towards attainable by unswerving devotion. Lalit Gupta us. Knowledge is praised in verse 18 of chap- If one truly wants to understand what Yoga as skill in action(Yogah karmasu ter 7 where Lord states that he holds a The gifted singer whose musical voice echoed the is YOGA there is no other book other than kausalam) When you invoke God in your Janani as his very self. Action is praised earthly sounds of melody and became synonym with Bhagavad Gita which can give a compre- actions then you even do not claim the in verse 19 of chapter 3 where Lord states Dogra ethos, Malika Pukhraj, will always remain inex- hensive meaning of the word yoga. Bha- doership of actions. The action loses its that by doing his duty without attachment tricable part of modern Dogra lore as well as the shared gavad Gita as a scripture is Brahmavidya power to bind you and your action become man attains to Supreme. In a number of legacy of the sub-continent. Malika Pukhraj was born and to realize It Gita teaches Yogashas- efficient means for liberation. For this one verses of the Gita knowledge, devotion in 1912, in village Mirpur, on the banks of the River tra. The yoga of Gita is a practical disci- has to be endowed with wisdom. There and action are combined to enable a Akhnoor. When she grew up her mother moved to Rajinder Bazaar, Kanak Mandi area of Jammu then pline for realization of God or Brah- devotee to come to God. -

Association of Physicians of Pakistani Descent of North America Volume 19, Number 2 Fall 2009

APPNA N E W S L E T T E R A quarterly publication of the Association of Physicians of Pakistani Descent of North America Volume 19, Number 2 Fall 2009 What’s Inside ... San Francisco Meeting a huge success! Health Reform incomplete without any Tort Reform – Editorial Winter Meeting in Karachi, December 29-31, 2009 NiagarSeptembera Falls 25-27, 2009 Niagara Falls, Ontario, Canada Association of Physicians of Pakistani Descent of North America APPNA N E W S L E T T E R A quarterly publication of the Association of Physicians of Pakistani Descent of North America Volume 19, Number 2 Fall 2009 6414 S. Cass Avenue, Westmont, IL 60559 • Phone 630-968-8585 • Fax 630-968-8677 • www.appna.org • [email protected] Editorial APPNA Newsletter Volume 19, Number 2 Publisher: APPNA Health Care Reform President: Syed Samad, MD Zia Moiz Ahmad, MD President Elect: Zeela Munir, MD Secretary: Manzoor ariq, MD reasurer: Saima Zaar t is how one views access to health care that de- Immediate Past President: fines how one approaches the debate over health Mahmood Alam I care reorm. Is access to basic health care a right or Publication Committee: a privilege? Is this a moral issue or a purely financial Chair: S. ariq Shahab, MD problem? Is this what defines our national charac- Cochair: Jamil Farooqui, MD ter or is it simply a question o what we can afford? Editor: Zia M Ahmad, MD Whereas there are credible and reasonable points to Urdu Editor: Salman Zaar, MD be made or both the positions, we strongly eel that Designed & Printed by access to basic health care is a right o citizenship. -

Curriculum of Gender Studies Bs & Ms

CURRICULUM OF GENDER STUDIES BS & MS (Revised 2017) HIGHER EDUCATION COMMISSION ISLAMABAD - PAKISTAN 1 CURRICULUM DIVISION, HEC Prof. Dr. Mukhtar Ahmed Chairman, HEC Mr. Muhammad Raza Chohan Director General (Academics) Dr. Muhammad Idrees Director (Curriculum) Syeda Sanober Rizvi Deputy Director (Curriculum) Mr. Riaz-ul-Haque Assistant Director (Curriculum) Mr. Muhammad Faisal Khan Assistant Director (Curriculum) 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction 7 2. Rationale 11 3. Standardized Template for Four-Year 13 4. Model Scheme of Stuides for BS 4 Year 16 5. Introduction to Gender Studies 17 6. Women and the Feminist Movements: A Global Perspective 21 7. Curriculum for MS in Gennder Studies 91 8. Rrecommendations 178 3 PREFACE The curriculum, with varying definitions, is said to be a plan of the teaching-learning process that students of an academic programme are required to undergo. It includes objectives & learning outcomes, course contents, scheme of studies, teaching methodologies and methods of assessment of learning. Since knowledge in all disciplines and fields is expanding at a fast pace and new disciplines are also emerging; it is imperative that curricula be developed and revised accordingly. University Grants Commission (UGC) was designated as the competent authority to develop, review and revise curricula beyond Class-XII vide Section 3, Sub-Section 2 (ii), Act of Parliament No. X of 1976 titled “Supervision of Curricula and Textbooks and Maintenance of Standard of Education”. With the repeal of UGC Act, the same function was assigned to the Higher Education Commission (HEC) under its Ordinance of 2002, Section 10, Sub-Section 1 (v). In compliance with the above provisions, the Curriculum Division of HEC undertakes the revision of curricula after every three years through respective National Curriculum Revision Committees (NCRCs) which consist of eminent professors and researchers of relevant fields from public and private sector universities, R&D organizations, councils, industry and civil society by seeking nominations from their organizations. -

Annual Report 2008-09 University of Peshawar NWFP, Pakistan

Annual Report 2008-09 University of Peshawar NWFP, Pakistan University of Peshawar Annual Report 2008-09 University of Peshawar N-W.F.P, Pakistan University of Peshawar In the name of ALLAH, The most Beneficient, the most Merciful Prepared by the Directorate of Planning & Development University of Peshawar. Views/ comments/ suggestion for further improvement may be forwarded to Director Planning & Development. Table of Contents Annual Report 2008-09 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECTIVE SUMMRY...............................................................................................6 VICE-CHANCELLOR’S MESSAGE .......................................................................7 FACULTIES.................................................................................................................8 Faculty of Arts and Humanities.........................................................................................8 Department of Anthropology........................................................................................................ 11 Department of Archaeology.......................................................................................................... 14 Department of History .................................................................................................................. 20 Department of English and Applied Linguistics ...........................................................................25 Department of Philosophy............................................................................................................29 -

The Teachers/Officers with an Ampersand (&) Appearing Against Their Name in the Last Column Have Been Provisionally Indicated in the Seniority List

The teachers/officers with an ampersand (&) appearing against their name in the last column have been provisionally indicated in the seniority list. They are requested to contact the district EMIS cell or the relevant DEO to provide the missing details or rectify the erroneous entry. In case the relevant teacher/officer does not respond within one month of display of these lists on the department website, then his/her name would be removed from the seniority list and his/her name will be deferred when being considered for promotion. Tentative Seniority list of Female J.V.T S. No Pers.no. Name Fname Date of Birth Date of Appointment To be Verified 1 20309776 HAMIDA BEGUM KARIM DAD 14.01.1958 03.01.1973 2 20215610 HAMIDA BAGUM NAWAB KHAN 05.01.1959 15.06.1973 & 3 20026429 SHAHIDA ROZI KHAN ROZI KHAN 09.12.1958 25.06.1973 4 20024446 HUSSAN ARA ABDUL QADIR 27.07.1973 27.07.1973 & 5 20284688 ZEENAT BEGUM GHULAM HUSSAIN 02.02.1959 11.07.1974 6 20157939 KHALIDA RASHID ABDUL RASHID 14.06.1958 15.10.1974 7 20027095 NASREEN AKHTAR RUSTIM KHAN 07.04.1957 22.02.1975 8 20027133 SARDAR BIBI MUHAMMAD HUSSAIN 11.05.1958 29.09.1975 9 20098206 AMINA ABDUL RAZIQ 02.03.1957 04.11.1975 10 20028313 SHAMSHAD KAUSAR GHULAM HUSSAIN 22.02.1958 08.11.1975 11 20027153 SURRIYA JAMAL FAQIR MOHAMMAD KHAN 23.02.1957 02.03.1976 12 20159936 ZAHIDA BATOOL MOHAMMAD AKBAR 07.08.1958 17.03.1976 13 20026519 NASIM AKHTAR INAYAT INYAT ULLAH 01.03.1957 19.04.1976 14 20189725 SADIYA PERVEEN MUHAMMAD ALI 30.01.1958 29.06.1976 15 20024151 RAFIAT JABEEN QURBAN HUSSIN 20.10.1976 20.10.1976 & 16 20153471 YASMEEN AKHTAR NASEEM HUSSAIN 06.06.1958 08.12.1976 17 20027063 RAFIA KALSOOM. -

List of Candidates Advertisement No

BALOCHISTAN PUBLIC SERVICE COMMISSION List of Candidates Advertisement No. 09/2016 Lecturer English (Female) BPS-17 in Education Department (Collegiate Branch) Local/ S# Roll No Name Father's Name Zone Domicile 1 2651 ABIDA ILYAS MUHAMMAD ILYAS L/ZHOB ZHOB ZONE 2 2652 ABIDA KHAN TAREEN AMEER KHAN TAREEN L/LORALAI ZHOB ZONE 3 2653 AFSHAN GUL MARRI GULHASSAN MARRI L/KOHLU SIBI ZONE 4 2654 AFSHAN SABEEN RIASAT ALI D/LORALAI ZHOB ZONE 5 2655 ALIA SAUD SAUD AHMED D/KALAT KALAT ZONE 6 2656 ALIYA NAEEM MUHAMMAD NAEEM SHAH L/SHERANI ZHOB ZONE 7 2657 AMBREEN REHMAT ULLAH L/KHARAN KALAT ZONE L/QILLA 8 2658 AMNA KAKAR NASRULLAH KHAN KAKAR ZHOB ZONE SAIFULLAH 9 2659 ANAM KHAN SANNA ULLAH D/ZHOB ZHOB ZONE 10 2660 ANILA HABIB HAJI HABIB UR REHMAN L/NOSHKI QUETTA ZONE 11 2661 ANILA KHADIM HUSSAIN KHADIM HUSSAIN L/JAFFERABAD NASIRABAD ZONE SARDAR DOULAT KHAN L/QILLA 12 2662 ARIFA GUL ZHOB ZONE JOGEZAI SAIFULLAH 13 2663 ASHRAFIA MUHAMMAD RAMZAN L/LORALAI ZHOB ZONE D/QUETTA 14 2664 ASIA NAZISH MOHAMMAD RAFIQ QUETTA CITY (CITY) 15 2665 ASIYA MUSTAFA GHULAM MUSTAFA L/KALAT KALAT ZONE 16 2666 ASMA MOHAMMAD ASHRAF L/KHUZDAR KALAT ZONE 17 2667 ASMA SHAH BUKHSH SHAH BUKHSH L/KALAT KALAT ZONE 18 2668 ASYA BALOCH HABIB ULLAH L/KALAT KALAT ZONE 19 2669 AYESHA ABDUL QUDDUS L/PISHIN QUETTA ZONE 20 2670 AYSHA GHULAM NABI GHULAM NABI L/PISHIN QUETTA ZONE 21 2671 BAKHT NAMA KHILJI ABDUL RAUF KHILJI L/QUETTA (CITY) QUETTA CITY D/QUETTA 22 2672 BAKHT SULTANA IQBAL HUSSAIN QUETTA CITY (CITY) 23 2673 BANADI KHURSHEED KHURSHEED L/KECH MEKRAN ZONE 24 2674 BANAFSHA JAVED JAVED