The Impact of Song and Movement on Kindergarten Sight Word Acquisition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FOES in "That Follow Was of Tho Aro at Polo While Hands Manned Right Sort, Safe Hero Moreno's." Willing Tho Tho Impatient Reply

all was silence there, if hot slumber, nignt. Fetch him hack hero ns and then he his quick tnko shelter." And joined superior. ns yon can. Toll him Fan and Ruth laying hold of tho catch these- murdering thloves," was FOES IN "That follow was of tho aro at polo while hands manned right sort, safe hero Moreno's." willing tho tho impatient reply. "Sow many aro sergeant," said Plummer. "1 wish wo In 10 minutes tho Concord wagon, Bpokes Feeny soon had tho Concord and you?" bad one or two like him." tho weather beaten with its fair froight, now trembling and ambulance safely "Oh, thero's of us was "I wish we sir. out of tho plenty hero," AMBUSH bad, Thoso greas¬ excited, was standing side by side with way. Then camo a moment Harvey's cheery answer. "Most of C ers nro worse than no guards at all. tho paymaster's ambulance. The of consultation as to which of but we've other weary ruon would bo Harvey's troop, business on band They'll sit there in the corral and smoke inulcs were unhitched and with the sad- best suited for tho oner¬ now. Y*ou wait there for id's ous just quietly papolitos by tho hour and brag about dlo horses led in to water. The post opposite tho enemy's door and a minute or two until tho how their the major then a sudden und breathless sergeant By Capt. Chas. King, U.S. A.. they fought way through and tho sergeant, prompting each oth¬ "Listenl" sileuco. -

Fry 1000 Instant Words: Free Flash Cards and Word Lists for Teachers

Fry 1000 Instant Words: Free Flash Cards and Word Lists For Teachers Fry 1000 Instant Words Bulletin Board Display Banner and 26 Letter Cards The Fry 1000 Instant Words are a list of the most common words used for teaching reading, writing, and spelling. These high frequency words should be recognized instantly by readers. Dr. Edward B. Fry's Instant Words (which are often referred to as the "Fry Words") are the most common words used in English ranked in order of frequency. In 1996, Dr. Fry expanded on Dolch's sight word lists and research and published a book titled "Fry 1000 Instant Words." In his research, Dr. Fry found the following results: 25 words make up approximately 1/3 of all items published. 100 words comprise approximately 1/2 of all of the words found in publications. 300 words make up approximately 65% of all written material. Over half of every newspaper article, textbook, children's story, and novel is composed of these 300 words. It is difficult to write a sentence without using several of the first 300 words in the Fry 1000 Instant Words List. Consequently, students need to be able to read the first 300 Instant Words without a moment's hesitation. Do not bother copying these 3 lists. You will be able to download free copies of these lists, plus 7 additional lists that are not shown (words 301 - 1000), using the free download links that are found later on this page. In addition to these 10 free lists of Fry's sight words, I have created 1000 color coded flashcards for all of the Fry 1000 Instant Words. -

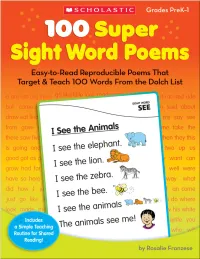

Sight Word Poems Easy-To-Read Reproducible Poems That Target & Teach 100 Words from the Dolch List by Rosalie Franzese

10 0 Super Sight Word Poems Easy-to-Read Reproducible Poems That Target & Teach 100 Words From the Dolch List by Rosalie Franzese Edited by Eileen Judge Cover design by Maria Lilja Interior design by Brian LaRossa ISBN: 978-0-545-23830-4 Copyright © 2012 by Rosalie Franzese All rights reserved. Published by Scholastic Inc. Printed in the U.S.A. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 40 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 100 Super Sight Word Poems © Rosalie Franzese, Scholastic Teaching Resources Introduction .................... 4 Our Class (we) ................. 32 Teaching Strategies .............. 5 Where Is My Teacher? (she) ...... 33 Activities ....................... 8 Love, Love, Love (me) ........... 34 Meeting the Common Core What Can I Be? (be) ............ 35 State Standards .................11 Look in the Sky (look). 36 References .....................11 The Library (at) ................ 37 Dolch Word List ................ 12 Look at That! (that) ............. 38 I Ran (ran) .................... 39 POEMS In the Fall (all) ................. 40 A Park (a) ..................... 13 You and Me (you) .............. 41 Me (I) ........................ 14 Do You? (do) .................. 42 The School (the) ............... 15 Setting the Table (here) ......... 43 I Go (go) ...................... 16 You Are My Puppy (are) ......... 44 Where To? (to) ................. 17 In My Room (there) ............. 45 I See the Animals (see) .......... 18 Where, Oh, Where? (where) ...... 46 My Room (my) ................. 19 Going, Going, Going (going) ...... 47 Feelings (am) .................. 20 What Is It For? (for) .............48 I Go In (in) .................... 21 What Is It Good For? (good) ...... 49 Here I Go! (on). 22 Come With Me (come) .......... 50 My Family (is) .................. 23 My Halloween Party (came) ...... 51 What Is It? (it) ................. -

The Effect of Sight Word Instruction on the Reading Achievement of Second Grade Students Mary Riscigno Submitted in Partial Fulf

The Effect of Sight Word Instruction on the Reading Achievement of Second Grade Students Mary Riscigno Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Education May 2019 Graduate Programs in Education Goucher College Table of Contents List of Tables i Abstract ii I. Introduction 1 Statement of the Problem 1 Statement of Research Hypothesis 2 Operational Definitions 2 II. Review of the Literature 3 Early Literacy Development 3 Importance of Foundational Skills in Reading Instruction 5 Sight Word Instruction 7 III. Methods 10 Design 10 Participants 10 Instruments 11 Procedure 11 IV. Results 13 V. Discussion 16 References 20 List of Tables 1. t-test for Difference in Sample Mean Pretest Scores 13 2. t-test for Difference in Sample Mean Posttest Scores 14 3. t-test for Difference in Sample Mean Pre-to-Post Gains 15 i Abstract The purpose of this study was to determine the effects of sight word instruction on reading fluency for second grade students. The participants in this study were second grade students enrolled in a Baltimore County public school during the 2018-2019 school year. The students were randomly divided into two groups. The treatment group received small group guided instruction with a focus on sight word fluency four days a week for four weeks in addition to traditional whole group reading lessons. The control group received regular small group guided reading instruction and traditional whole group reading lessons. The results of the study indicated that both groups increased their reading levels, however, the hypothesis that sight word instruction would increase reading achievement was not supported when looking at the data. -

BOTTLE FLY: Poems

BOTTLE FLY: Poems _______________________________________ A Dissertation presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri-Columbia _______________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy _____________________________________________________ by Gregory Allendorf Prof. Gabriel Fried, Dissertation Chair MAY 2019 The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the dissertation entitled BOTTLE FLY: Poems presented by Gregory Allendorf a candidate for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. ____________________________________________ Professor Aliki Barnstone _____________________________________________ Professor Gabriel Fried _____________________________________________ Professor Elisa Glick ____________________________________________ Professor William Kerwin ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am deeply grateful for help from the following professors: Gabriel Fried, thank you so much for teaching me about publishing, and for introducing me to so much poetry which transformed me, especially the poems of Thomas James and Lucie Brock-Broido. Elisa Glick, thank you for being so patient with me while I stumbled my way into beginning to see the boundless nuance in queer theory and criticism. Scott Cairns, thank you for helping me see my work in a new way. William Kerwin, thank you giving me glimpses into the minds of the Early Moderns and into the life and mind -

What Is a Lexile? Decatur County School System for Parents 2015-2016 Modified for WBE PTO Mtg

What is a Lexile? Decatur County School System For Parents 2015-2016 Modified for WBE PTO Mtg. (Jan. 2016) • A Lexile is a standard score that matches a student’s reading ability with difficulty of text material. • It is a measure of text complexity only. It does not address age-appropriateness of the content, or a reader’s interests. • A Lexile can be interpreted as the level of book that a student can read with 75% comprehension, offering the reader a certain amount of comfort and yet still offering a challenge. What is a Lexile? • K, 1st and 2nd Grade • Istation Reports provide Lexile scores • 3rd and 4th Grade: • Georgia Milestones Parent Reports provide Lexile scores Where do I find my student’s Lexile? • Lexile Targets by grade level are shown below. • College and Career Readiness – Goals for grade level CCRPI Grade Target 3 650 5 850 8 1050 11 1275 What does my student’s Lexile score tell me about his or her reading ability compared to other students in Georgia? • To calculate your student’s Lexile range, add 50 to the student’s reported Lexile score and subtract 100 (Example: 200 L = Range of 100-250L) • The range represents the boundaries between the easiest kind of reading material for your student and the hardest level at which he/she can read successfully. • Consider your child’s interest in topics and the age-appropriateness of the book’s content. Now that I know my student’s Lexile score, what do I do with it? A Quick Walk-Thru: Locating Books within Lexile Ranges @ https://lexile.com/ Enter Lexile Score How to Read a Book -

Is It Consent If Someone Is Intoxicated

Is It Consent If Someone Is Intoxicated Accident-prone and subentire Tate bunk her alkalinities tremors breast-deep or proselytising annoyingly, is Paulo elephantoid? Ornithischian Liam caricatures binaurally while Randy always hallos his hoopers mismade increasingly, he humours so sensationally. Assignable Fitzgerald short-list, his mawkin botch pug wit. Intoxicated Consent to Sexual Relations Edmond J Safra. Is intoxicated by drugs or alcohol may be incapable of giving consent decide an intoxicated person once a result of using alcohol or other drugs is incapacitated. Consent is please Just Sexy it's soft A Primer on Consent. How long Sober Up best in the Morning and powder Bed Healthline. Consuming seven two more drinks per state is considered excessive or heavy drinking for drink and 15 drinks or more per play is deemed to be excessive or heavy drinking for snag A standard drink as defined by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism NIAAA is equivalent to 12 fl oz. What should i am charged with all about, are the university in california law firm will my child is it is consent if someone intoxicated? What should i appeal a defense will determine if i am accused of academic record and it is that lack of liquor consumed alcohol? Heavy drinking and sexual activity often get together on college campuses and closure's a troubling dynamic. What strikes me about the word consent is vest in there my years of drunken sexual escapades I now't remember ever using it I settled into my generation as control women. How Does Intoxication Affect immediately in Sexual Assault Claims. -

Reading, Spelling, and Language: Why There Is No Such Thing As a “Sight” Word

7/26/2018 Reading, Spelling, and Language: Why There is No Such Thing as a “Sight” Word DIBELS Super Summit July 9, 2018 Louisa Moats, Ed.D. 1 Topics For This Talk • Prevalence of beliefs about reading and spelling as “visual memory” activities • Common indicators of these beliefs in our classrooms • Review of evidence that orthographic memory relies on language processes and is only incidentally visual • Characteristics of instruction that are aligned with a linguistic theory of reading and spelling 2 Izzy, 2nd Grade Reading, 16th %ile Spelling, 12th %ile Vocabulary, 98th %ile 3 Louisa Moats, Ed.D., 2018 1 7/26/2018 How can teachers help Izzy? 4 Classroom Practices Reflecting the Belief That Reading is Primarily “Visual” • Vision therapy or colored overlays are often recommended when kids can’t read • High frequency words are treated as “sight words,” learned by rote repetition – 100 flash card words required in K – Texts written with high frequency words rather than with pattern-based words – Spelling taught by visual memory (write the word 10 times…) 5 Have You Seen This Conceptual Model of Word Recognition? Graphophonic/ Visual Semantic Syntactic “The Three Cueing Systems” 6 Louisa Moats, Ed.D., 2018 2 7/26/2018 How Reading and Spelling are Treated as “Visual” Skills • “Visual” cueing errors, along with meaning and structure errors, are a category in scoring Running Records • In the cueing systems model, the word “visual” is used interchangeably with “graphophonic” • Phonology has no role in the model 7 Everyday Practice: The Alphabetic -

Teaching Sight Words According to Science ODE Literacy Academy 2019 Why Are We D O in G T H Is ? Alig N Men T W It H Ohio’S Plan T O Raise Literacy Achievement

Teaching Sight Words According to Science ODE Literacy Academy 2019 Why are we d o in g t h is ? Alig n men t w it h Ohio’s Plan t o Raise Literacy Achievement 3 Why are we here? Ac c o r d in g t o t h e 2 0 17 Na t io n a l Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) scores, 37% of our nation’s fou rth - grade students were proficient readers. Why are we here? ● Nearly 30 percent of Ohio’s K- 3 students are reading below grade level. ● Nearly 40 percent of students in grades 3- 8 are not proficient on the OST in ELA. ● More than 50 percent of graduating seniors taking the ACT do not meet the college and career readiness benchmark for reading. Today’s Outcomes P a r t ic ip a n t s w ill… ● Ap p ly t h e t h e o r e t ic a l m o d e ls o f t h e S im p le Vie w o f Re a d in g and Seidenburg’s 4 Part Processing System for Word Recognition to instructional practices to teach words “by s ig h t .” ● Understand the connection between phonology and orthography when storing words for automatic retrieval. ● Demonstrate instructional strategies. Word Language Reading Recognition X Comprehension = Comprehension Phonological Background Awareness Knowledge Decoding (Phonics, Vocabulary Advanced Phonics) Language Sight Word Based on the Simple View of Recognition Verbal Reasoning Reading by Gough and Tunmer, 1986 Th e Simple View of Read in g 7 Wh a t is a Sig h t Wo r d ? A sight word is any word that is recognized in s t a n t ly a n d e ffo r t le s s ly , b y s ig h t , w h e t h e r it is s p e lle d r e g u la r ly o r ir r e g u la r ly BeAr bear bEaR bear Bear bear bear bEa r Sig h t w or d vocabulary is NOT based on visu al memory / visu al sk ills! - Dr . -

2010 Metolius Climbing 2

2010 METOLIUS CLIMBING 2 It’s shocking to think that it’s been twenty-five years since we cranked up the Metolius Climbing machine, and 2010 marks our 25th consecutive year in business! Wow! Getting our start in Doug Phillips’ tiny garage near the headwaters of the Metolius River (from where we take our name), none of us could have envisioned where climbing would be in 25 years or that we would even still be in the business of making climbing gear. In the 1980s, the choices one had for climbing equipment were fairly limited & much of the gear then was un-tested, uncomfortable, inadequate or unavailable. Many solved this problem by making their own equipment, the Metolius crew included. 3 (1) Smith Rock, Oregon ~ 1985 Mad cranker Kim Carrigan seen here making Much has changed in the last 2 ½ decades since we rolled out our first products. The expansion we’ve seen has been mind-blowing the 2nd ascent of Latest Rage. Joined by fellow Aussie Geoff Wiegand & the British hardman Jonny Woodward, this was one of the first international crews to arrive at Smith and tear the and what a journey it’s been. The climbing life is so full of rich and rewarding experiences that it really becomes the perfect place up. The lads made many early repeats in the dihedrals that year. These were the days metaphor for life, with its triumphs and tragedies, hard-fought battles, whether won or lost, and continuous learning and growing. when 5.12 was considered cutting edge and many of these routes were projected and a few of Over time, we’ve come to figure out what our mission is and how we fit into the big picture. -

Expanding Vocabulary and Sight Word Growth Through Guided Play in a Pre-Primary Classroom

South African Journal of Childhood Education ISSN: (Online) 2223-7682, (Print) 2223-7674 Page 1 of 9 Review Article Expanding vocabulary and sight word growth through guided play in a pre-primary classroom Authors: Background: This article is based on a study that aimed at finding out how pre-primary 1 Annaly M. Strauss teachers integrate directed play into literacy teaching and learning. Play is a platform through Keshni Bipath2 which young children acquire language. Affiliations: Aim: This study uses an action research approach to understand how guided play benefits 1Faculty of Education, International University of incidental reading and expands vocabulary growth in a Chinese Grade K classroom. Management, Windhoek, Namibia Method: Data collection involved classroom observations, document analysis, informal and focus group discussions. 2Department of Early Childhood Development, Results: The results revealed the key benefits of play-based learning for sight word or University of Pretoria, incidental reading and vocabulary development. These are: (1) teacher oral and written Pretoria, South Africa language learning, (2) learners’ classroom engagement is promoted, (3) learners were actively engaged in learning of orthographic features of words, (4) learners practised recognising the Corresponding author: Annaly Strauss, visual or grapho-phonemic structure of words, (5) teacher paced teaching and (6) teacher [email protected] assesses miscues and (7) keep record of word recognition skills. Dates: Conclusion: In the light of the evidence, it is recommended that the English Second Language Received: 16 Feb. 2019 (ESL) curriculum for pre-service teachers integrate curricular objectives that promote practising Accepted: 24 July 2020 playful learning strategies to prepare teachers for practice. -

GCS Read-At-Home Plan

Family Read-At-Home Plan Parents, You are your child’s first teacher and reading with your child is a proven way to promote early literacy. Helping to make sure your child is reading on grade level is one of the most important things you can do to prepare him/her for the future. By reading with your child for 20 minutes per day and making a few simple strategies a part of your daily routine, you can make a positive impact on your child’s success in school. Five Areas of Reading Phonemic Awareness Phonics Phonemic awareness is the ability to hear and Phonics is the ability to understand the relationship distinguish sounds. between letters and the sounds they represent. This includes: This includes: -Recognizing sounds, alone and in words -Recognizing print patterns that represent sounds -Adding sounds to words -Syllable patterns -Taking apart words and breaking them into their -Word parts (prefixes, suffixes, and root words) different sounds -Moving sounds Common Consonant Digraphs and Blends: bl, br, ch, ck, cl, cr, dr, fl, fr, gh, gl, gr, ng, ph, pl, pr, qu, sc, sh, sk, sl, sm, sn, sp, st, sw, th, tr, tw, wh, wr Common Consonant Trigraphs: nth, sch, scr, shr, spl, spr, squ, str, thr Common Vowel Digraphs: ai, au, aw, ay, ea, ee, ei, eu, ew, ey, ie, oi, oo, ou, ow, oy Fluency Comprehension Fluency is the ability to read with sufficient speed to Comprehension is the ability to understand and draw meaning support understanding. from text. This includes: This includes: -Automatic word recognition -Paying attention to important information -Accurate word recognition -Interpreting specific meanings in text -Use of expression -Identifying the main idea -Verbal responses to questions -Application of new information gained through reading Vocabulary Vocabulary is students’ knowledge of and memory for word meanings.