9.2 Trace- 100- the Day Our World Changed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Trelavour Prazey, St. Dennis, St. Austell, PL26 8BP Asking Price Of

• Three Bedroom Cornish Cottage Trelavour Prazey, St. Dennis, St. Austell, PL26 8BP Millerson Estate Agents welcome to the market this three bedroom, stone fronted Cornish Cottage which has been updated • Updated Throughout throughout by the current owners. It offers off road parking, a detached garage and generous gardens. To view now call on 017 26 • Large Gardens 72289. • Garage & Off Road Parking Asking Price Of £220,000 Property Description PROPERTY DESCRIPTION Millerson Estate Agents are delighted to bring this three bedroom Cornish cottage to the market situated in the village of St. Dennis. The current owners have made numerous improvements and updates to the property. To summarise, the accommodation comprises of: Living room, dining room, kitchen, utility and cloakroom. To the first floor there are three bedrooms and a bathroom. Externally the property offers driveway parking, a detached garage as well as front and rear gardens. THE ACCOMODATION COMPRISES:- All dimensions are approximate. Entrance door to: ENTRANCE PORCH 4' 3" x 3' 7" (1.3m x 1.1m) Door to: ENTRANCE HALL Stairs leading to the first floor. Door to: DINING ROOM 14' 1" x 9' 2" (4.3m x 2.8m) Window to the front with shutters. Vinyl click flooring. Door to: LIVING ROOM 14' 1" x 12' 1" (4.3m x 3.7m) Multi fuel burner set in a gorgeous exposed stone fireplace. Vinyl click flooring. Window to the front with shutters. Consumer unit. KITCHEN 12' 9" x 11' 1" (3.9m x 3.4m) Maximum measurement. Measured wall to wall. Stainless steel 1 and 1/2 bowl sink and drainer with mixer tap housed within a straight edge work surface with matching base and wall storage cupboards. -

St Austell & Mevagissey

Information Classification: PUBLIC Agenda Meeting: St Austell & Mevagissey Community Network Panel Meeting This is a virtual meeting, please click on link below; Click here to join the meeting Date & Time: Thursday 9th September at 6.00pm Agenda Approx Timings 1. Welcome 6.00-6.05 (a) Teams etiquette (Community Link Officer) (b) Round table introductions (c) Apologies for absence and late arrival 2. Public Participation (up to 30 minutes) 6.05-6.15 An opportunity for members of the public to raise any questions. 3. St Austell River Project 6.15-6.40 Following the proposed adoption of the St Austell River project by the Community Network, the attached discussion document has been circulated. Daniel Griffiths from the Environment Agency will present their data on the St Austell river quality and ecological standards. https://environment.data.gov.uk/catchment-planning/. 4. Housing 6.40-7.00 Cllr Oliver Monk, Portfolio holder for Housing, will outline Cornwall Council’s priorities for housing. 5. Notes of the last meeting (attached and previously circulated) 7.00-7.05 To agree the notes and consider any matters arising. 6. Update on Climate Crisis working group 7.05-7.10 Verbal report from Helen Nicholson, Community Link Officer. 7. Traffic and Highways issues 7.10-7.15 Opportunity to raise issues which cannot be reported via; https://www.cornwall.gov.uk/report-something/ 8. Feedback on local issues from Parish and Town Councils 7.15-7.40 Information Classification: PUBLIC Agenda Approx Timings An opportunity for Town and Parish representatives to raise issues of relevance to the Community Network area: • Carlyon Parish Council • Mevagissey Parish Council • Pentewan Valley Parish Council • St Austell Bay Parish Council • St Austell Town Council • St Ewe Parish Council • St Goran Parish Council • St Mewan Parish Council 9. -

Car Free Days out

CAR FREE DAYS OUT ... how to enjoy St Austell without the car! SW09 A trip to Mevagissey and Fowey by boat! Grid Ref After experiencing the sights of Mevagissey, from the harbour you can take the pedestrian boat ferry to Fowey and enjoy two of Cornwall’s most picturesque and contrasting harbours A:7 by land and sea. Then you can return either by the ferry to Mevagissey or alternatively take the bus from Fowey (Bus Number 25) to return you to St Austell. MevagisseyThere is a bit of almost everything in this day out. Firstly, of course, an essential A trip to ingredient to every Cornish summer - the boat trip! This is the Cornish mainland’s only open sea crossing - so be prepared for a fairly exhilarating ride when the wind is from the south Mevagissey or east! It is one of the most memorable sea journeys to be had anywhere in the southwest and Fowey of England and takes in some of the county’s most beautiful coastline (and the occasional dolphin or basking shark). Mevagissey to Fowey Ferry Lighthouse Pier Mevagissey Tel: 07977 203394 [email protected] www.ferry.me.uk First sailing 10am (9.30am 19th July – 9th September) Runs daily May – September inclusive. (weather permitting – check website or phone if in doubt) Mevagissey is a delightful small working harbour with around 70 licensed fishing boats and a variety of pleasure craft. There is an aquarium displaying most of our native fish and Return boat fare: a really outstanding folk museum, both of which are free to visit. -

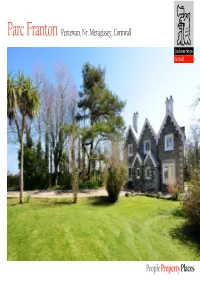

Parc Franton Pentewan, Nr. Mevagissey, Cornwall

Parc Franton Pentewan, Nr. Mevagissey, Cornwall An individual country home recently refurbished, close to the quaint harbourside village of Mevagissey Guide Price £575,000 Features The Property • Generous Kitchen/Breakfast Room Originally part of the Heligan Estate and still • Sitting Room retaining many original architectural features, Parc Franton has been comprehensively • Dining Room refurbished incorporating oak and ceramic • Snug floors, pleasing and well-appointed • Cloakroom kitchen/breakfast room in a range of cream units • Utility Room and a four oven Aga. The property is secluded down a long driveway which provides total • 5 Bedrooms privacy. An adjacent paddock of about 1 acre • En-Suite Shower Room has been leased for some 30 years or so by the • Walk in Wardrobe owners of Parc Franton from the Tremayne • Family Bathroom Estate and it is envisaged that this arrangement could be continued. • Double Carport • Games Room • Stables The Location • Mature Gardens The house is surrounded by its gardens and • 1 Acre Paddock (on Lease) grounds in a secluded setting down a driveway • Secluded Setting of 100 yards or so overlooking rolling countryside and close to the popular harbourside village of Mevagissey. The Lost Distances Gardens of Heligan are close by and can be seen • Mevagissey 1.3 miles across the fields from the rear gardens. Much of • St Austell 4.8 miles the surrounding countryside still remains in the • Truro 19 miles ownership of the Tremayne Estate. • Heligan Gardens 1.3 miles The Cathedral City and administrative centre of • Eden Project 9 miles Truro is some 19 miles to the west with the main commercial town of St Austell some 5 miles to (distances approximately) the north east, both providing multiple shopping facilities and main line rail stations to London Paddington. -

Mevagissey Parish Neighbourhood Development Plan

Mevagissey Parish Neighbourhood Development Plan Picture Copyright Sarah Olson, New York, www.sarah-olson.com Plan for the Period 2017 - 2032 Issue 2.0 Mevagissey Neighbourhood Development Plan February 2018 Issue 2.0 February 2018 1 Introduction Those who know Mevagissey would describe it as the classic working Cornish fishing port which is active all year round. It stands alone, untouched and geographically distinct from nearby conurbations. The village church dates from the thirteenth century and the streets have a medieval layout. History has it that Mevagissey was a centre for smuggling in the eighteenth century, building fast cutters for the smugglers and the revenue men alike. The port has an inner harbour which dries out between tides and a deeper outer harbour. A large and growing number of fishing boats work from the harbour which is surrounded by a conservation area largely consisting of ancient fishermen's cottages, renovated fish processing buildings and the grander houses of one-time merchants. The harbour hosts a boat-builder and repair yard, an aquarium and a history museum. The permanent population of Mevagissey has fallen slightly over the last 200 years but since 1930, the buildings in the village have more than doubled. This can be accounted for by lower densities of family occupation, but more significantly to improved mobility in the latter 20th century giving rise to a demand for second homes and as a retirement destination. Greater mobility has, however, not greatly influenced the employment prospects either in Mevagissey or in Cornwall as a whole, so living standards among residents deny many of them the opportunity to aspire to home ownership within the village. -

CORNWALL. [ KELJ Y's

1180 SHO CORNWALL. [ KELJ_y's SHOPKEEPERS-continued. Staple John, 69 Pydar street, Truro Thomas Nicholas, Trequite, St. Kew, Rowe Wm. St. Blazey, Par Station R.S.O Stentiford H. Gerrans,Grampound Road Wadebridge R.S.O Rowett Thos. Market st. East Looe R.S.O Stephens Edward Bloye, Latchley, Gun- Thomas Richd. Southgate st. Redruth Rowland Thomas, Coppetthorne, Pound- nislake, Tavistock Thomas Richard, Tregenna pi. St. Ives stock, Stratton R.S.O Stephens Miss Eva, Fore !!treet, St. Thomas Samuel, High street, Penzance Rowling John, Leeds Town, Hayle Columb Major R.S.O Thomas S. D. 79 Killigrew st. Falmouth Rowse J.St. Blazey gate,ParStationR.S.O Stephens Mrs. Jane, 76 Plain-an- Thomas Thomas, Church town, Zennor, Row-e J. L. St. Blazey, ParStation R.S.O Gwarry, Redruth St. Ives R.S.O Rule Miss H. Condurrow, Camborne Stephens John, Godolphin, Helston Thomas William, Carnkie, Redruth Rule Mrs. Mary Ann, Troon, Camborne Stephens Jonathan, Millbrook, Maker, Thomas Wm. Germoe, Marazion R.S.O RundelMrs.E.St.Blazey,ParStationR.S.O Devonport Thorne William,Fore st.East Looe R.S.O Rundle Mrs. F. St. Eval, St. Jssey R.S.O Stephens Mrs. Maria, St. Blazey, Par Tingcombe George, Camelford Rundle Miss G. J. Heiston rd. Penryn Station R.S.O Tom Henry, St. Mabyn, Bodmin Rundle Mrs. J. Trebollett, Launceston Stephens Mrs. Rebecca, Vicarage, St. Toman Mrs. John, Chapel street, Rundle J. H. St. Thomas street, Penryn Agnes, Scorrier R.S.O Newlyn, Penzance Ruse John, Medrase, Camelford Stephens Richard, Towan cross, Mount, Toms Mrs. Eliza, St. -

The Cornish Way an Forth Kernewek

Map The Cornish Way An Forth Kernewek Consideration for Others Care for the Environment • Follow the Highway Code. • Leave your car at home if possible. Can you reach the start of your journey by bike or public transport? • Please be courteous to other users, and do not give the ‘The Cornish Way’ and its users a bad name. • Follow the Countryside Code. In particular: take litter home with you; keep to the routes provided and • Give way to walkers and, where necessary, horses. shut any gates; leave wildlife, livestock, crops and Slow down when passing them! machinery alone; and make no unnecessary noise. • Warn other users of your presence, particularly when approaching from behind. Warn a horse with Contacts some distance to spare - ringing a bell or calling out a greeting will avoid frightening the horse. Cornwall Council www.cornwall.gov.uk/cornishway • Keep to the trails, roads, byways or tel: 0300 1234 202 and bridleways. www.nationalrail.co.uk • Do not ride or cycle on footpaths. www.sustrans.org.uk • Respect other land management industries such as www.visitcornwall.com farming and forestry. • Please park your bike considerately. © Cornwall Council 2012 Part of cycle network Lower Tamar Lake and Cycle Trail Bude Stratton Marhamchurch Widemouth Bay Devon Coast to Coast Trail Millbrook Week St Mary Wainhouse Corner Warbstow Trelash proposed Hallworthy Camel - Tarka Link Launceston Lower Tamar Lake and Cycle Trail Camelford National Cycle Network 2 3 32 Route Number 0 5 10 20 Bude Stratton Kilometres Regional Cycle Network 67 Marhamchurch -

Neighbourhood Planning

Neighbourhood Planning Update • January 2019 Quick links ●Current Consultations ●Government Legislation ●Toolkit and guide notes ●Other Information ●Town, Parish & City Council Online Mapping Welcome to the Neighbourhood Planning e- bulletin for January 2019 The New Year has got off to a busy start with multiple designations received and plans submitted, with many other plans within the statutory process progressing through to being made. This year we are focussing on the quality of the guidance that we provide to Steering Groups. To that end, please be aware that the guidance notes on the Neighbourhood Planning webpage are being updated. We are also offering the opportunity for groups to meet with other service officers during the quarterly surgeries that we host, to ensure that we can support groups in producing high quality NDPs going forward. Melissa Burrow has been welcomed into the Neighbourhood Planning Team, and there will be some restructuring regarding named officers for Steering Groups. An email will follow in the coming weeks to update groups on this. We are looking forward to a productive year of Neighbourhood Planning across Cornwall. Neighbourhood Planning Team Telephone: 0300 1234 100 www.cornwall.gov.uk Neighbourhood Planning Surgeries Neighbourhood Planning in Cornwall The next round of Neighbourhood Planning surgeries will be held in March. This will provide 128 Steering Groups with an opportunity to speak to Town and Parish Councils Neighbourhood Planning officers about any queries submitted Designation and be provided with some guidance on the Applications development of their plan. Each steering group can book a 45 minute slot, which will need to be booked in 116 advance. -

Kelly's Directory 1883

Extract from Kelly’s Directory of Cornwall, 1883 (page 178) MEVAGISSEY Mevagissey (anciently Lamarrack) is a township, parish, and seaport town situated on a fine bay, 3 miles west from the Blackhead, and 1 mile north from Chapel Point by the road, 6 miles south from St Austell, and 15 south- east from Truro; it is in the Eastern division of the county, east division of the hundred of Powder, St Austell union and county court district, rural deanery of St Austell, archdeaconry of Cornwall, and diocese of Truro. A pier was erected in 1770-3, and has since been greatly improved, the area encircled by the pier will contain 60 or 70 vessels, it is dry at low water, but has a good bed for the shipping to rest on. The church of St Mevan and St Issy, situated a little to the north-west of the town, is a plain building of stone, consisting of chancel, nave of four bays, aisle and south transept, the lower portion only of the tower remains and contains 1 bell, dated 1684: at the east end of the chancel is a very fine mural monument to Lewis Dart esq 1632: there is also a tomb with effigies to Otwell Thill, 1617, and Mary, his wife, to the Carew family and others: the font is Norman; there are sittings for 300 persons. The church, dating from an early period, is now in a very dilapidated state. The register dates from the year 1598. The living is a vicarage, tithe rent-charge £161, gross yearly value £265, with residence and 23 acres of glebe and fish tithes, in the gift of and held since 1882 by the Rev. -

St. Austell Methodist Circuit 12/7 Plan of Services – December 2020 No

2018 Mrs. J. Petzing, 58 Victoria Road, Roche, St. Austell, PL26 8JG Tel: 891920 THE METHODIST CHURCH CHAIR OF THE CORNWALL DISTRICT CIRCUIT STEWARDS REV. STEVEN WILD, 4 UPLAND CRESCENT, TRURO, TR1 1LU, TEL: 01872 261327 Mrs. E. Foster, Coppers, 11 Duporth Bay, St. Austell, PL26 6AG Tel: 74347 Mrs. L. Hawken, 5 Meadow Close, St. Stephen, St. Austell, PL26 7PE Tel: 822343 Mrs. J. Taylor, 40 Chyandor Close, St. Blazey, Par, PL24 2LP Tel: 816867 ST. AUSTELL METHODIST CIRCUIT 12/7 PLAN OF SERVICES – DECEMBER 2020 NO. 114 PREACHERS AND HELPERS FROM OTHER CIRCUITS AND CHURCHES WORSHIP LEADERS (completed – New Course) CIRCUIT MINISTERS Anne Keast, 6 Highfield Avenue, St. Austell, PL25 4SN Tel: 61444 REV. STEPHEN CADDICK (Superintendent), 71 Meadway, St. Austell, PL25 4HT Tel: 61341 Carole Thornton, 26 Trenant Road, Tywardreath, Par, PL24 2QJ Tel: 812198 REV. DR. DAVID HART, The Manse, Valley Road, Mevagissey, St. Austell, PL26 6SB Tel: 844471 Edna Yelland, West Winds, Crown Road, Whitemoor, St. Austell, PL26 7XH Tel: 822689 REV. PAUL PARKER, The Manse, Molinnis Road, Bugle, St. Austell, PL26 8QJ Tel: 850504 WORSHIP LEADERS (in training from September 2015 – New Course) LAY STAFF (APPOINTED BY CIRCUIT) Julie Ketch, Linford Cottage, 21 Vicarage Road, Tywardreath, Par, PL24 2PQ Tel: 816246 MR. JOHN KEAST, OBE, BD, AKC, MA, 6 Highfield Avenue, St. Austell, PL25 4SN Tel: 61444 MRS. CAROL BAINES, Trelawney, Tregoney Hill, Mevagissey, St. Austell, PL26 6RF Tel: 843378 Louise Sandford-Webb, 189 Manor View, Par, PL24 2EP Tel: 810944 MRS. SUE BATTISON, 67 Tremodrett Road, Roche, St. Austell, PL26 8JB Tel: 890428 SUBSTITUTE AND VISITING PREACHERS MRS. -

Mevagissey Wills

Mevagissey Wills and/or associated documents available from Kresen Kernow (formerly the Cornwall Record Office (CRO) and the National Archive (NA) Links are to the transcripts available from the parish page Source Ref. No. Title Date Proved CRO ACP/WR/183/111 Will Indexes, Archdeaconry Court of Probate, Mevagissey 1572-1636 CRO AP/C/4 Will of Thomas Chapman of Mevagissey 1601 CRO AP/W/6 Will of William William alias John of Mevagissey 1601 CRO AP/H/24 Will of Richard Harris of Mevagissey 1602 CRO AP/J/22 Will of Michael Jagman of Mevagissey 1603 CRO AP/C/45 Will of John Cock of Mevagissey 1603-1604 CRO AP/C/87 Will of John Cock of Mevagissey 1605 CRO AP/S/134 Will of George Stephens of Mevagissey 1607 CRO AP/L/74 Will of Walter Long alias Lang of Mevagissey 1607 CRO AP/S/158 Will of William Stephens of Mevagissey 1608 CRO AP/W/163 Will of William Williams of Mevagissey 1609-1610 CRO FS/3/852 Will of Richard Coundy, gentleman, of Bodrugan, Mevagissey 1610 CRO AP/S/237 Will of John Sherham of Mevagissey 1612 CRO AP/B/289 Will of William Bowden of Mevagissey 1612 CRO AP/S/263 Will of Rosye Stephens, widow, of Mevagissey 1613 CRO AP/T/250 Will of John Thomas alias Luke of Mevagissey 1615 CRO AP/B/372 Will of John Blerick of Mevagissey 1615-1616 CRO AP/B/392 Will of William Bake of Mevagissey 1616 CRO AP/P/315 Will of Jane Polsewe, widow, of Mevagissey 1616 CRO AP/J/203 Will of Walter Jenckinge of Mevagissey 1616 NA PROB 11/130/409 Will of John Blarack of Mevagissey, Cornwall 23/10/1617 NA PROB 11/130/410 Will of Richard Osborne, Yeoman of -

Fowey to Mevagissey Fowey to St Austell

Fowey to Mevagissey 24 via Par | St Blazey | St Austell Mondays to Saturdays except bank holidays buses towards Mevagissey buses towards Fowey Fowey Safe Harbour Hotel 0635 2000 2200 2359 Mevagissey Trevarth 0714 1900 2100 2300 Four Turnings Garage 0639 2004 2204 0003 Pentewan bus shelter 0719 1905 2105 2305 Castle Dore Tywardreath Turn 0642 2007 2207 0006 London Apprentice opp Phone Box 0722 1908 2108 2308 Tywardreath St Andrews Church 0645 2010 2210 0009 Tregorrick Turn 0725 1911 2111 2311 Par opp Railway Station 0648 2013 2213 0012 South Street 0728 1914 2114 2314 52 Par Moorland Road & Par Green 0650 2015 2215 0014 St Austell Bus & Rail Station arr 0731 1917 2117 2317 St Blazey Polgrean Place 0654 2019 2219 0018 St Austell Bus & Rail Station dep 1920 2120 2320 St Blazey opp Old Roselyon Manor 2022 2222 0021 Charlestown opp Old Chapel 1926 2126 2326 Biscovey School Close 2025 2225 0024 Holmbush Holmbush Inn 1928 2128 2328 Holmbush opp Holmbush Inn 0700 2029 2229 0028 Biscovey opp School Close 1932 2132 2332 Charlestown Old Chapel 2031 2231 0030 St Blazey Old Roselyon Manor 1935 2135 2335 St Austell Bus & Rail Station arr 0706 2036 2236 0035 St Blazey opp Polgrean Place 1938 2138 2338 St Austell Bus & Rail Station dep 0645 1840 2040 2240 0039 Par Moorland Road & Par Green 1942 2142 2342 St Austell South Street 0648 1843 2043 2243 0042 Par Railway Station 1944 2144 2344 Tregorrick Turn 0651 1846 2046 2246 Tywardreath opp St Andrews Church 1947 2147 2347 London Apprentice Phone Box 0654 1849 2049 2249 Castle Dore Golant Turn 1950 2150