Downloaded from ORCA, Cardiff University's Institutional Repository

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

INTRODUCTION the BMW Group Is a Manufacturer of Luxury Automobiles and Motorcycles

Marketing Activities Of BMW INTRODUCTION The BMW Group is a manufacturer of luxury automobiles and motorcycles. It has 24 production facilities spread over thirteen countries and the company‟s products are sold in more than 140 countries. BMW Group owns three brands namely BMW, MINI and Rolls- Royce. This project contains detailed information about the marketing and promotional activities of BMW. It contains the history of BMW, its evolution after the world war and its growth as one of the leading automobile brands. This project also contains the information about the growth of BMW as a brand in India and its awards and recognitions that it received in India and how it became the market leader. This project also contains the launch of the mini cooper showroom in India and also the information about the establishment of the first Aston martin showroom in India, both owned by infinity cars. It contains information about infinity cars as a BMW dealership and the success stories of the owners. Apart from this, information about the major events and activities are also mentioned in the project, the 3 series launch which was a major event has also been covered in the project. The two project reports that I had prepared for the company are also a part of this project, The referral program project which is an innovative marketing technique to get more customers is a part of this project and the other project report is about the competitor analysis which contains the marketing and promotional activities of the competitors of BMW like Audi, Mercedes and JLR About BMW BMW (Bavarian Motor Works) is a German automobile, motorcycle and engine manufacturing company founded in 1917. -

Sir Frank Cooper on Air Force Policy in the 1950S & 1960S

The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors concerned and are not necessarily those held by the Royal Air Force Historical Society Copyright © Royal Air Force Historical Society, 1993 All rights reserved. 1 Copyright © 1993 by Royal Air Force Historical Society First published in the UK in 1993 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing. Printed by Hastings Printing Company Limited Royal Air Force Historical Society 2 THE PROCEEDINGS OFTHE ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORICAL SOCIETY Issue No 11 President: Marshal of the Royal Air Force Sir Michael Beetham GCB CBE DFC AFC Committee Chairman: Air Marshal Sir Frederick B Sowrey KCB CBE AFC General Secretary: Group Captain J C Ainsworth CEng MRAeS Membership Secretary: Commander P O Montgomery VRD RNR Treasurer: D Goch Esq FCCA Programme Air Vice-Marshal G P Black CB OBE AFC Sub-Committee: Air Vice-Marshal F D G Clark CBE BA Air Commodore J G Greenhill FBIM T C G James CMG MA *Group Captain I Madelin Air Commodore H A Probert MBE MA Group Captain A R Thompson MBE MPhil BA FBIM MIPM Members: A S Bennell Esq MA BLitt *Dr M A Fopp MA PhD FMA FBIM A E Richardson *Group Captain N E Taylor BSc D H Wood Comp RAeS * Ex-officio The General Secretary Regrettably our General Secretary of five years standing, Mr B R Jutsum, has found it necessary to resign from the post and the committee. -

QUAD-CITIES BRITISH AUTO CLUB 2017 Edition / Issue 12 5 December 2017

QUAD-CITIES BRITISH AUTO CLUB 2017 Edition / Issue 12 5 December 2017 CHRISTMAS EDITION CONTENTS The QCBAC 1 THE QCBAC The QCBAC was formed to promote interest and usage of any and all British Christmas Puzzle 1 cars. The QCBAC website is at: http://www.qcbac.com QCBAC Contacts 1 Christmas Dinner 2 Clues and Puzzle Clues 2 word list are on Puzzle Word List 2 page 2. Board Meeting 3 Car of the Month 4 British Auto News 15 Crossword Answer 20 Question Answer 20 Thanks to the Board 20 QCBAC CONTACTS President Jerry Nesbitt [email protected] Vice President Larry Hipple [email protected] Secretary John Weber [email protected] Treasurer Dave Bishop [email protected] Board member Carl Jamison [email protected] Board member Gary Spohn [email protected] Autofest Chair Frank Becker [email protected] 2017 Santa Test Run Membership Chair Pegg Shepherd [email protected] Publicity Chair Glen Just [email protected] Page 1 of 20 QCBAC CHRISTMAS DINNER BRIT CAR QUESTION The QCBAC Christmas will take place on 10 December at Montana Jacks, 5400 27th St, Moline, IL. Bring a wrapped $5 gift for the traditional secret gift You are probably familiar exchange. with the British driver Malcolm Campbell who RSVP to Linda Weber: [email protected] held numerous land speed by 30 November so the appropriate space can be reserved. records from 1924 to 1935. The 1935 301.3 mph LSR was made in the 1931 Blue CHRISTMAS PUZZLE CLUES Bird powered by a 2,300 hp Rolls Royce V12. -

Katalog Över Automobilhistoriska Klubbens Bibliotek 2011-02-22

Katalog över Automobilhistoriska klubbens bibliotek 2011-02-22 Fabrikat Titel Författare Förlag Utgiven ISBN Abarth Abarth the man, the machines Greggio Luciano giorgioNADAeditore 2002 88-7911-263-5 AC AC Two-litre Salons & Buckland Sports cars Archibald Leo Veloce Publishing 2002 1-903706-24-6 AC mini marque history series Watkins Martyn Foulis Haynes 1976 0-85429-204-7 The Classic AC, Two Litre to Cobra McLellan John Motor Racing Publ. 1985 0-900549-98-x Cobra. The First 40 Years Legate Trevor MBI Motorbooks 2006 0-7603-2423-9 Adler Adler Automobile 1900-1945 Oswald Werner Motorbuch Verlag 1981 3-87943-783-1 AGA AGA-bilen första "folkvagnen" Almqvist Ebbe Gazetten 1990 AUDI Alle AUDI Automobile 1910-1980 Oswald Werner Motorbuch Verlag 1980 3-87943-685-1 Alfa Romeo Alfissimo! Owen David Osprey 1979 0-85045-327-5 Tutte Vetture Dal 1910. All Cars From 1910 Fusi Luigi Emmenti Grafica 1978 Giulietta Sprint 1954-2004 Alferi Bruno Automobilia 2004 88-7960-171-7 Fantastic Alfa Romeo Greggio Luciano Motorbooks International 1996 0-7603-0237-5 Alfa Romeo Alfetta GT Owen David Osprey Autohistory 1985 0-85045-620-7 Viva Alfa Romeo Owen David Foulis Haynes 1976 0-85429-207-1 Alfa Romeo - Milano Frostick David Dalton Watson 1974 0901564-125 Alfa Romeo Green Evan Evan Green PTY Limited 1976 0-959-6637-0-3 Alfa Romeo a history Hull P & Slater R Casell & Company 1964 Le Alfa Romeo Jano Vittorio Autocritica 1982 Alfa Romeo Disco Volante Anderloni Bianchi Automobilia 1993 88-7960-002-8 Alfa Romeo The Legend Revived Styles David G. -

Postmaster & the Merton Record 2017

Postmaster & The Merton Record 2017 Merton College Oxford OX1 4JD Telephone +44 (0)1865 276310 www.merton.ox.ac.uk Contents College News Features Records Edited by Merton in Numbers ...............................................................................4 A long road to a busy year ..............................................................60 The Warden & Fellows 2016-17 .....................................................108 Claire Spence-Parsons, Duncan Barker, The College year in photos Dr Vic James (1992) reflects on her most productive year yet Bethany Pedder and Philippa Logan. Elections, Honours & Appointments ..............................................111 From the Warden ..................................................................................6 Mertonians in… Media ........................................................................64 Six Merton alumni reflect on their careers in the media New Students 2016 ............................................................................ 113 Front cover image Flemish astrolabe in the Upper Library. JCR News .................................................................................................8 Merton Cities: Singapore ...................................................................72 Undergraduate Leavers 2017 ............................................................ 115 Photograph by Claire Spence-Parsons. With MCR News .............................................................................................10 Kenneth Tan (1986) on his -

Wessex Ways’ July 2017

WESSEX VEHICLE PRESERVATION CLUB FOUNDED 1971 www.wvpc.org.uk ‘WESSEX WAYS’ JULY 2017 VEHICLE OF THE MONTH The Napier-Railton is an aero-engined race car built in 1933, designed by Reid Railton to a commission by John Cobb. It was driven by Cobb, mainly at the Brooklands race track where it holds the all-time lap record of 143.44 mph which was set in 1935. This stands in perpetuity as the circuit was used for military purposes during the second World War and was never used as a racing track again. Between 1933 and 1937 the Napier-Railton broke 47 World speed records at Brooklands, Montlhéry and Bonneville Salt Flats in Utah.The car is powered by the 6.1:1 high compression naturally aspirated W12 Napier Lion engine of 23.944 litres capacity, producing 580 brake horse power at 2,585 rpm. the12 cylinders are in three banks of four (broad-arrow configuration), hence the triple exhaust system, and the engine has standard aerospace features such as dual ignition. The non syncromesh crash gearbox (aptly named for the horrible noises caused by a mis-shift) has 3 ratios. Fuel consumption was approximately 5 mpg. Although capable of 168 mph the car has rear wheel braking only. Brave photographers at the top of the Brooklands banking, with the Napier Railton leaping clear of the uneven concrete track at high speed. Page 1. CHAIRMAN’S CHATTER Hi Everyone, Not much to say this month as the editor is off on his travels – it’s OK for some. I have just received news that a good day was had by all who went to the Lake Shipyard, where the weather was dry but quite windy. -

Important Collectors' Motor Cars

Important Collectors’ Motor Cars Knokke-Le Zoute, Belgium I 5 October 2018 LOT 40 Ex-Cassius Clay (Muhammad Ali) 1970 ROLLS-ROYCE SILVER SHADOW CONVERTIBLE Muhammad Ali and Diana Ross next to the Rolls-Royce outside Caesars Palace in Las Vegas before his fight against Joe Bugner, 14 February 1973. © Getty images © LAT As Head of the European Motor Car Department for Bonhams it gives me very great pleasure to return to Knokke Le Zoute for the sixth auction sale in this luxurious holiday resort which is the epicentre of lifestyle and art on the Belgian seaside. My special thanks go to Count Leopold Lippens, mayor of the town and president of the Zoute Automobile Club, the town of Knokke-Heist and all of its officials and the organisers of the Zoute Grand Prix. We have sourced an exciting and varied selection of automobilia and collectors’ motor cars, with a particularly strong accent on quality rather than quantity and with numerous lots offered without reserve allowing buyers not vendors to determine the current market correct values. Whether you are an experienced bidder wishing to enhance your collection or a first time buyer, I am confident that we offer something that will appeal to you – in addition where else in the world can you one day tell your grandchildren that you bid on and hopefully purchased the car they are driving in a spectacular tent on a beach! In our commitment to holding this sixth sale here in Belgium’s most prestigious seaside resort we very much wish to make a statement of our belief in the success of the five previous editions and in continuing the construction of a long and rewarding partnership with the above, as well as the event partners and sponsors over the coming years and share with them a common goal of providing another rewarding experience with the very best service. -

September 20062006

BackfireBackfire SeptemberSeptember 20062006 TheThe MagazineMagazine ofof thethe BristolBristol PegasusPegasus MotorMotor ClubClub Cover : Mike McBraida with Mitsubishi Evo VI 2006 Pegasus Castle Combe Day - Photo Andy Moss Events For September Monday 11 th - Club Night For the September club night we intend to add a few novelties to our usual informal meeting. We intend to have a selection of motorsport video games and a radio controlled car autotest, as well as a scalextric set. Wheatsheaf Winterbourne 8.30 pm. Saturday 16 th – Ariel Cars and Haynes Visit We have arranged a club visit to Ariel cars – manufacturers of the Ariel Atom, followed by a trip to the Haynes Motor Museum ( no doubt with a visit to a good pub for lunch between the two ). The Ariel visit is free, entrance to Haynes will be at the discounted rate of £5.50. For more information contact Ken Robson on 07753 987028 or email [email protected] Remember not to leave it until the last minute as you will almost certainly lose out. Sunday 24 th – Autotest There is still some doubt about this event at the time of going to press because of Redevelopment work at our usual venue of Rolls-Royce in Patchway. As soon as we have a decision on use of the venue we will post an update on the club website – anyone who is interested in entering and does not have access to the web should contact Kieron Winter on 01275 373363 ( evenings ) for further information. Events For October Monday 9th - Club Night – Charity Quiz Night The Quiz at the club night in October will be a charity event in aid of St Peter's Hospice. -

The Bristol Bullet – It Could Be Yours!

www.wheels-alive.co.uk The Bristol Bullet – it could be yours! Published: 6th August 2020 Author: Robin Roberts Online version: https://www.wheels-alive.co.uk/the-bristol-bullet-it-could-be-yours/ www.wheels-alive.co.uk Bristol Cars liquidation sale includes the first Bristol Bullet… …writes Robin Roberts. Car enthusiasts are getting a once-in-a-lifetime chance to buy a unique one-off four-year-old British sports car, and it could cost them hundreds of thousands of pounds. The Bristol Bullet roadster is among items being disposed of by joint liquidators of Bristol Cars, which folded earlier this year. Jeremy Frost and Patrick Wadsted of Frost Group Ltd, appointed as Joint Liquidators, have been on an extensive hunt for the car maker’s assets and this discovered a secret storage facility with a large quantity of designs, manuals, parts and tooling covering the many years of the businesses’ existence. Included as well were a collection of rare and vintage cars, in www.wheels-alive.co.uk various stages of completeness, including the first “Bristol Bullet” car. This collection is expected to command a high price at auction when it goes up on https://bidspotter.co.uk, with some of the lots including the “Bristol Bullet” being described as so unique as to make estimating the price likely to be realized impossible to determine. That is not to say the Liquidators expectations have anything other than increased by this finding. Hertfordshire based machinery and business asset valuers and experts in selling this type of material, Wyles Hardy & Co, have been instrumental in dealing with the valuation and forthcoming sale of the collection. -

Section 1 of Draft in Service Exhaust Emission Standards for Road

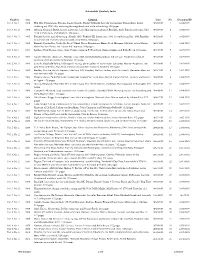

1 2 3 4 Manufacturer/Marque (b) (c) (b) (c) (d) (e) (f) (a) Normal Idle Speed (a) Fast Idle Speed Max CO Min Max Max CO Max HC Min Max Min Max Min Oil Limit (% Limit Limit Limit Limit Lambda Lambda Limit Limit Temp(°C) Vol) (RPM) (RPM) (%Vol) (PPM) (RPM) (RPM) ABARTH Abarth 500 and Abarth Punto 500/500C, 595/595C, Grande Punto & Punto Evo 0.3 700 800 0.2 200 0.97 1.03 2100 2700 80 500 1.4 T-Jet 135 bhp & 160 bhp 0.3 690 790 0.2 200 0.97 1.03 2400 2600 97 Punto 1.4 MultiAir 165 bhp & 180 bhp 0.3 700 800 0.2 200 0.97 1.03 2400 2600 93 AC Cars AC Superblower 4949cc V8 Engine Code LL 0.5 625 775 0.3 200 0.95 1.05 2500 3000 80 AC Ace V8 4949cc Engine Code ACA Automatic 0.5 800 950 0.3 200 0.95 1.05 2800 3100 80 4949cc Engine Code ACA Manual 0.5 725 875 0.3 200 0.95 1.05 2800 3100 80 AC 302 CRS 4949cc V8 0.5 625 775 0.3 200 0.95 1.05 2500 3100 80 AC 212 3506cc V8 0.5 700 950 0.3 200 0.95 1.05 2500 3100 80 ALFA ROMEO Engine Codes appear on the VIN Plate as well as on the Engine Block. 33 1.7 16V with Engine Code 30747 0.5 800 900 0.3 200 0.97 1.03 2500 2900 80 1.7 8V with Engine Code 30737 0.5 900 1050 0.3 200 0.97 1.03 2500 2900 80 164 2.0 T.S with Engine Codes 06416 and 64103 0.5 790 890 0.3 200 0.97 1.03 2500 2900 80 V6 12V with Engine Codes 6412 and 64301 0.5 700 800 0.3 200 0.97 1.03 2500 2900 80 V6 24V 0.5 675 825 0.3 200 0.97 1.03 2500 2900 80 Spider Spider with Engine Code 01588 0.5 750 850 0.3 200 0.97 1.03 2500 2900 80 Spider/GTV 2.0 T.S 16V 0.5 750 890 0.3 200 0.97 1.03 2500 2900 80 Page 1 1 2 3 4 Manufacturer/Marque (b) (c) (b) (c) -

Motoring History Rolls in Star Watch

NEWS TIPS [email protected] NEWS 9 Motoring history rolls in National car club rally reaches South East coast England could enjoy the natural Victoria, its head offi ce in Melbourne spectacle during an 18-day tour of and branches in South Australia, ALEXAL regional Australia in their beloved New South Wales and Queensland. McGREGORM Bristol vehicles. More than 100 members are alex@tbwale .com.au Club secretary Bob Leffl er said the involved with the club, coming from group had enjoyed the journey so far all areas of Australia, New Zealand after previous group road trips in and the United Kingdom. A CONVOY of more than 25 Bristol their reliable and superb Bristols. A national rally bringing together model cars wound through the “We are a very active car club and up to 40 Bristols from all states is South East last week as part of a often take our beloved cars out to held every two years, while regular monumental road trip organised other parts of the country and on trips usually occur every two to four by the Bristol Owners Club of this trip we have had a couple from months. Australia. England ship their Bristol over and The car enthusiasts spent two The dazzling cars pulled up at join the convoy,” he said. nights in Mount Gambier during the Blue Lake so that visitors “Bristols were built to endure their stay in the Limestone Coast and members of the club from long road trips and are extremely last Tuesdayto Friday. New South Wales, Tasmania, reliable.” Queensland, Victoria and even The club was established in Continued page 12 MORE PICTURES PAGE 12 AROUND THEY GO: Bristol cars form the shape of a rotary engine at Southend Point as a Tiger Moth plane, piloted by Kym Redman, soars above. -

Automobile Quarterly Index

Automobile Quarterly Index Number Year Contents Date No. DocumentID Vol. 1 No. 1 1962 Phil Hill, Pininfarina's Ferraris, Luigi Chinetti, Barney Oldfield, Lincoln Continental, Duesenberg, Leslie 1962:03:01 1 1962.03.01 Saalburg art, 1750 Alfa, motoring thoroughbreds and art in advertising. 108 pages. Vol. 1 No. 2 1962 Sebring, Ormond Beach, luxury motorcars, Lord Montagu's museum at Beaulieu, early French motorcars, New 1962:06:01 2 1962.06.01 York to Paris races and Montaut. 108 pages. Vol. 1 No. 3 1962 Packard history and advertising, Abarth, GM's Firebird III, dream cars, 1963 Corvette Sting Ray, 1904 Franklin 1962:09:01 3 1962.09.01 race, Cord and Harrah's Museum with art portfolio. 108 pages. Vol. 1 No. 4 1962 Renault; Painter Roy Nockolds; Front Wheel Drive; Pininfarina; Henry Ford Museum; Old 999; Aston Martin; 1962:12:01 4 1962.12.01 fiction by Ken Purdy: the "Green Pill" mystery. 108 pages. Vol. 2 No. 1 1963 LeMans, Ford Racing, Stutz, Char-Volant, Clarence P. Hornburg, three-wheelers and Rolls-Royce. 116 pages. 1963:03:01 5 1963.03.01 Vol. 2 No. 2 1963 Stanley Steamer, steam cars, Hershey swap meet, the Duesenberg Special, the GT Car, Walter Gotschke art 1963:06:01 6 1963.06.01 portfolio, duPont and tire technology. 126 pages. Vol. 2 No. 3 1963 Lincoln, Ralph De Palma, Indianapolis racing, photo gallery of Indy racers, Lancaster, Haynes-Apperson, the 1963:09:01 7 1963.09.01 Jack Frost collection, Fiat, Ford, turbine cars and the London to Brighton 120 pages.