Perspective Structure in Agatha Christie's Five Little Pigs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Verdict Programme

Next at the Good Companions ... Hansel & Gretel A family pantomime December 12th, 13th, 14th & 15th Box Office: 07931 237206 If you would like to be involved contact Sylvia Daker for further details: 020 8959 2194 The Good Companions have a very extensive wardrobe and props collection and are very pleased to offer items for hire. Further information Tel: 020 7704 0299 www.thegoodcompanions.org.uk Tea and coffee is available for a small donation. The wine bar is open 30 minutes before the performance and for 20 minutes throughout the interval. A Letter From The Captain Backstage Dear Friends, I consider myself to be very lucky to have been Captain of the GC’s a number of times but it really is an immense Production Manager - Dawn Oliver privilege to be holding that position as we celebrate our Stage Manager - Marek Wedler 80th Anniversary. I joined the group at the tender age of fifteen and have been a member ever since! It is a place Set & Construction - Iain Savage, Daniel where, like others, I have met many wonderful people, some of whom have become my closest friends - it is my extended family. Pocklington, Joyce As with all Amateur Dramatic Societies we have had our ups and downs. Digweed, Mick Toon & Many of you will recall our desperation when some of our money was members of the cast stolen, of course we all share in the great sadness of losing close friends, who have meant so much and I especially recall the tears streaming down Lighting - Marko Saha my face as I stood on the corner of Church Close and watched our home burn down to the ground. -

Agatha Christie - Third Girl

Agatha Christie - Third Girl CHAPTER ONE HERCULE POIROT was sitting at the breakfast table. At his right hand was a steaming cup of chocolate. He had always had a sweet tooth. To accompany the chocolate was a brioche. It went agreeably with chocolate. He nodded his approval. This was from the fourth shop he had tried. It was a Danish patisserie but infinitely superior to the so-called French one near by. That had been nothing less than a fraud. He was satisfied gastronomically. His stomach was at peace. His mind also was at peace, perhaps somewhat too much so. He had finished his Magnum Opus, an analysis of great writers of detective fiction. He had dared to speak scathingly of Edgar Alien Poe, he had complained of the lack of method or order in the romantic outpourings of Wilkie Collins, had lauded to the skies two American authors who were practically unknown, and had in various other ways given honour where honour was due and sternly withheld it where he considered it was not. He had seen the volume through the press, had looked upon the results and, apart from a really incredible number of printer's errors, pronounced that it was good. He had enjoyed this literary achievement and enjoyed the vast amount of reading he had had to do, had enjoyed snorting with disgust as he flung a book across the floor (though always remembering to rise, pick it up and dispose of it tidily in the waste-paper basket) and had enjoyed appreciatively nodding his head on the rare occasions when such approval was justified. -

Agatha Christie

book & film club: Agatha Christie Discussion Questions & Activities Discussion Questions 1 For her first novel,The Mysterious Affair at Styles, Agatha Christie wanted her detective to be “someone who hadn’t been used before.” Thus, the fastidious retired policeman Hercule Poirot was born—a fish-out-of-water, inspired by Belgian refugees she encountered during World War I in the seaside town of Torquay, where she grew up. When a later Poirot mystery, The Murder of Roger Ackroyd, was adapted into a stage play, Christie was unhappy that the role of Dr. Sheppard’s spinster sister had been rewritten for a much younger actress. So she created elderly amateur detective Jane Marple to show English village life through the eyes of an “old maid”—an often overlooked and patronized character. How are Miss Marple and Monsieur Poirot different from “classic” crime solvers such as police officials or hard-boiled private eyes? How do their personalities help them to be more effective than the local authorities? Which modern fictional sleuths, in literature, film, and television, seem to be inspired by Christie’s creations? 2 Miss Marple and Poirot crossed paths only once—in a not-so-classic 1965 British film adaptation of The ABC Murders called The Alphabet Murders (played, respectively, by Margaret Rutherford and Tony Randall). In her autobiography, Christie writes that her readers often suggested that she should have her two iconic sleuths meet. “But why should they?” she countered. “I am sure they would not enjoy it at all.” Imagine a new scenario in which the shrewd amateur and the egotistical professional might join forces. -

Hercule Poirot Mysteries in Chronological Order

Hercule Poirot/Miss Jane Marple Christie, Agatha Dame Agatha Christie (1890-1976), the “queen” of British mystery writers, published more than ninety stories between 1920 and 1976. Her best-loved stories revolve around two brilliant and quite dissimilar detectives, the Belgian émigré Hercule Poirot and the English spinster Miss Jane Marple. Other stories feature the “flapper” couple Tommy and Tuppence Beresford, the mysterious Harley Quin, the private detective Parker Pyne, or Police Superintendent Battle as investigators. Dame Agatha’s works have been adapted numerous times for the stage, movies, radio, and television. Most of the Christie mysteries are available from the New Bern-Craven County Public library in book form or audio tape. Hercule Poirot The Mysterious Affair at Styles [1920] Murder on the Links [1923] Poirot Investigates [1924] Short story collection containing: The Adventure of "The Western Star", TheTragedy at Marsdon Manor, The Adventure of the Cheap Flat , The Mystery of Hunter's Lodge, The Million Dollar Bond Robbery, The Adventure of the Egyptian Tomb, The Jewel Robbery at the Grand Metropolitan, The Kidnapped Prime Minister, The Disappearance of Mr. Davenheim, The Adventure of the Italian Nobleman, The Case of the Missing Will, The Veiled Lady, The Lost Mine, and The Chocolate Box. The Murder of Roger Ackroyd [1926] The Under Dog and Other Stories [1926] Short story collection containing: The Underdog, The Plymouth Express, The Affair at the Victory Ball, The Market Basing Mystery, The Lemesurier Inheritance, The Cornish Mystery, The King of Clubs, The Submarine Plans, and The Adventure of the Clapham Cook. The Big Four [1927] The Mystery of the Blue Train [1928] Peril at End House [1928] Lord Edgware Dies [1933] Murder on the Orient Express [1934] Three Act Tragedy [1935] Death in the Clouds [1935] The A.B.C. -

Download Poirot: Halloween Party Free Ebook

POIROT: HALLOWEEN PARTY DOWNLOAD FREE BOOK Agatha Christie | 336 pages | 03 Sep 2001 | HarperCollins Publishers | 9780007120680 | English | London, United Kingdom 35. Hallowe'en Party (1969) - Fraser Robert Barnard : "Bobbing for apples turns serious when ghastly child Poirot: Halloween Party extinguished in the bucket. Uploaded by Unknown on September 22, All Episodes Search icon An illustration of a magnifying glass. Mrs Goodbody. However, he commits suicide when two men, recruited by Poirot to trail Miranda, thwart him and save her life. What a joy it was to find out that we were going to get Poirot: Halloween Party new Poirots this summer where I live in the US, at least. You've just tried to add this show to My List. Edit Storyline When Ariadne Oliver and Poirot: Halloween Party friend, Judith Butler, attend a children's Halloween party in the village of Woodleigh Common, a young girl named Joyce Reynolds boasts of having witnessed a murder from years before. At a Hallowe'en party held at Rowena Drake's home in Woodleigh Common, thirteen-year-old Joyce Reynolds tells everyone attending she had once seen a murder, but had not realised it was one until later. Ariadne Oliver. Director: Charlie Palmer as Charles Palmer. Visit our What to Watch page. Plot Keywords. The television adaptation shifted the late s setting to the s, as with nearly all shows in this series. The Cold War is at its peak and the opponents are hostile. External Link Explore Now. The story moves along nicely, and the whole thing is visually appealing. Read by Hugh Fraser. -

"Verdict" Brought to Life in UD Theatre

University of Dayton eCommons News Releases Marketing and Communications 6-16-1983 "Verdict" Brought to Life in UD Theatre Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.udayton.edu/news_rls Recommended Citation ""Verdict" Brought to Life in UD Theatre" (1983). News Releases. 4382. https://ecommons.udayton.edu/news_rls/4382 This News Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Marketing and Communications at eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in News Releases by an authorized administrator of eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. The University rf Dayton News Release "VERDICT" BROUGHT TO LIFE IN UD THEATRE DAYTON, Ohio, March 16, 1983 The curtain of the University of Dayton's Boll Theatre will open Thursday, March 24 at 8 p.m. and the Performing and Visual A~ts Department will present Agatha Christie' s "Verdict." Performances will also be given Friday and Saturday at 8 p.m. According to director Robert Bouffier, S.M., Christie considered "Verdict" her best play except for "Witness for the Prosecution." There are no surprises in "Verdict"-- '~ he murder of Karl 1 s wife occurs on stage, in full view of the audience, so that ev~ry- one takes part in identifying the villain simultaneously, ex~ ept the police. The reystery is whether or not justice will be blind and the scales balanced by the playfs end. In "Verdict," everyone is a ·;·ictim. One almost cannot help but feel that each of the characters receives his measure of poetic justice. The main characters, Karl (David Lee Dutton) and Anya Hendryck (Jaye Liset), are German political exiles living i n England, unceremoniously evicted from their homeland for sheltering the family of one of Karl's colleagues. -

Plot of Agatha Christie's …

KULTURISTIK: Jurnal Bahasa dan Budaya Vol. 4, No. 1, Januari 2020, 56-65 PLOT OF AGATHA CHRISTIE’S … Doi: 10.22225/kulturistik.4.1.1584 PLOT OF AGATHA CHRISTIE’S THIRD GIRL Made Subur Universitas Warmadewa [email protected] ABSTRACT This research aimed to examine the parts of the plot structure and also the elements which build up the parts of the plot structure of this novel. The theory used in analyzing the data was the theory on the plot. The theoretical concepts were primarily taken from William Kenney’s book entitled How to Analyze Fiction (1996). Based on the analysis, the plot structure of Agatha Christie’s ‘Third Girl (2002) consisted of three parts: beginning plot, middle plot, and ending plot. The beginning plot of this novel told us about: (a) Hercule Poirot’s peaceful condition after having breakfast; (b) his attitude of scathing view on Edgar Allan Poe; (c) Miss. Norma’s performance with vacant expression; and (d) Hercule Poirot’s good relationship with Mrs Oliver and with Mrs Restarick. In the middle plot of this novel, the story of this novel presented about: (a) Mrs Restarick’s psychological conflict; (b) Andrew Restarick’s angriness because of David Baker’s relationship with his daughter, Miss Norma; and (c) Mrs Adriana’s unsuccessfulness to find Miss. Norma at Borodene Mansions. The events described in the complicating plot of this novel are about: (a) the investigation of Miss Norma as a suspected agent attempting to commit the murder of Mrs Restarick; (b) the secure of Miss Norma suspected to have committed murder by Dr. -

Hercule Poirot

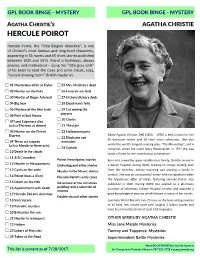

GPL BOOK BINGE - MYSTERY GPL BOOK BINGE - MYSTERY AGATHA CHRISTIE’S AGATHA CHRISTIE HERCULE POIROT Hercule Poirot, the “little Belgian detective”, is one of Christie's most famous and long-lived characters, appearing in 33 novels and 65 short stories published between 1920 and 1975. Poirot is fastidious, always precise, and methodical – using the “little gray cells” of his brain to read the clues and solve classic, cozy, “locked drawing room” British mysteries. 01 Mysterious affair at Styles 25 Mrs. McGinty's dead 02 Murder on the links 26 Funerals are fatal 03 Murder of Roger Ackroyd 27 Hickory dickory dock 04 Big four 28 Dead man's folly 05 Mystery of the blue train 29 Cat among the pigeons 06 Peril at End House 30 Clocks 07 Lord Edgeware dies (a/k/a Thirteen at dinner) 31 Third girl 08 Murder on the Orient 32 Halloween party Express Dame Agatha Christie, DBE (1890 – 1976) is best known for her 33 Elephants can 66 detective novels and 14 short story collections. She also 09 Three act tragedy remember (a/k/a Murder in three acts) wrote the world's longest-running play, “The Mousetrap”, and 6 34 Curtain romances under the name Mary Westmacott. In 1971 she was 10 Death in the clouds made a Dame for her contribution to literature. 11 A B C murders Poirot investigates: stories Born into a wealthy upper-middle-class family, Christie served in 12 Murder in Mesopotamia Underdog and other stories a Devon hospital during WWI, tending to troops coming back 13 Cards on the table Murder in the Mews: stories from the trenches, before marrying and starting a family in London. -

Re-Writing the Past, Autobiography and Celebrity in Agatha (1979): 'An

Street, S. C. J. (2020). Re-Writing the Past, Autobiography and Celebrity in Agatha (1979): ‘An Imaginary Solution to an Authentic Mystery’. Open Screens, 3(1), 1-30. [1]. https://doi.org/10.16995/os.34 Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record License (if available): CC BY Link to published version (if available): 10.16995/os.34 Link to publication record in Explore Bristol Research PDF-document This is the final published version of the article (version of record). It first appeared online via BAFTSS at http://doi.org/10.16995/os.34 . Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher. University of Bristol - Explore Bristol Research General rights This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the reference above. Full terms of use are available: http://www.bristol.ac.uk/red/research-policy/pure/user-guides/ebr-terms/ Research How to Cite: Street, S. 2020. Re-Writing the Past, Autobiography and Celebrity in Agatha (1979): ‘An Imaginary Solution to an Authentic Mystery’. Open Screens, 3(1): 2, pp. 1–30. DOI: https://doi.org/10.16995/os.34 Published: 09 July 2020 Peer Review: This article has been peer reviewed through the double-blind process of Open Screens, which is a journal published by the Open Library of Humanities. Copyright: © 2020 The Author(s). This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC-BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. -

Techniques of Detective Fiction in the Novelistic Art of Agatha Christie

,,. TECHNIQUES OF DETECTIVE FICTION IN THE NOVELISTIC ART OF AGATHA CHRISTIE A Monograph Presented to the Faculty of the Department of English Morehead State University In Partial .FUlfillment of the Requirements for the ~gree Master of Arts b;y Claudia Collins Burns Januar,r, 1975 ...... '. ~- ... '. Accepted by the faculty of the School of H,.;#t.,._j-f;l ..:.3 • Morehead State U¢versi~ in partial· fulfillment of tl!e requirements for the Master of Arts degree. ,·. •: - ',· .· ~.· '1' ' '· .~ ' . ,·_ " 1 J • ~ ,,., ' " . Directorno( Monograph j. ,- .. I . ' U.-g ·'-%· '- .. : . ,. •.·,' . ,• ·- ; -..: ' ~ ' .. ''· ,,, ··. TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page INTRODUCTION • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • l General Statement on the Nature of the }lonoeraph • l . ~ . 3 Previous Work • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 4 Purposes And Specific Elements to be Proven • • • 7 l. AGATHA CHRISTIE AND THE RULES OF DETECTIVE FICTION • 8 The Master Detective •• • • • • • • • • • . • • 8 Clues Before the RE;<itler. ........... • .. 30 Motives for the Crime • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 52 2. ELEMENTS OF SOCIOLOGICAL COMMENTARY IN THE FICTION OF AGATHA CHRISTIE . .. 6a Class Consciousness ................. 62 Statements About Writers and Writings • • • • • • 76 Role of Women Characters • • • • • • • • • • • • • 90 ;". 3. •· . 106 BIBLIOGRAPHY . ~ . 108 APPENDIX . ... ~·..... lll ii INTRODUCTION NATURE OF THE MONOGRAPH, PROCEDURE, PREVIOUS WORK, PURPOSES AND SPECIFIC ELEMENTS TO BE.PROVEN . '. I. GENERAL STATEMENT ON THE NATURE OF THE MONOGRAPH When -

Agatha Christie's Hercule Poirot the Case of the Careless Client February 22, 1945

Agatha Christie's Hercule Poirot The Case of the Careless Client February 22, 1945 Announcer Theme music Agatha Christie's Poirot Theme music From the thrill-packed pages of Agatha Christie's unforgettable stories of corpses, clues and crime, Mutual now brings you, complete with bowler hat and brave mustache, your favorite detective, Hercule Poirot, starring Harold Huber, in the case of The Careless Victim., Theme music Before meeting Hercule Poirot in his first American adventure, it seems only fitting for the millions of faithful readers who have followed the little Belgian detective's career in book form, to meet the famous lady who created this famous character. So it is our privilege to present a message from Agatha Christie introducing Hercule Poirot from London, England. The next voice you hear will be Miss Agatha Christie's. Go ahead, London. Agatha Christie I feel that this is an occasion that would have appealed to Hercule Poirot. He would have done justice to the inauguration of this radio program, and he might even have made it seem something of an international event. However, as he's heavily engaged on an investigation, about which you will hear in due course, I must, as one of his oldest friends, deputize for him. The great man has his little foibles, but really, I have the greatest affection for him. And it is a source of continuing satisfaction to me, that there has been such a generous response to his appearance on my books, and I hope that his new career on the radio will make many new friends for him among a wider public. -

The ABC Murders

LEVEL 4 Teacher’s notes Teacher Support Programme The ABC Murders Agatha Christie Chapters 1–2: Captain Arthur Hastings travels to London and goes to see his old friend, the retired Belgian EASYSTARTS detective, Hercule Poirot. Poirot shows Hastings a letter he has received in which he is told to watch out for Andover on the 21st of the month. The letter is signed ‘ABC’. Meanwhile, in another part of the country, a man LEVEL 2 named Alexander Bonaparte Cust takes a railway guide and a list of names from his jacket pocket. He marks the first name on the list. Some days later, Poirot receives a phone call from the police, telling him that an old woman LEVEL 3 called Ascher has been murdered in her shop in Andover. Poirot and Hastings travel to Andover and the police tell them that they suspect her husband, a violent drunk. LEVEL 4 About the author Poirot’s letter, however, casts some doubt on the matter and an ABC railway guide has also been found at the Agatha Christie was born in 1890 in Devon, England. scene of the crime. Poirot and Hastings visit the police She was the youngest child of an American father and doctor and then they go to see Mrs Ascher’s niece, Mary an English mother. Her father died when she was eleven Drower, who is naturally very upset. and the young Agatha became very attached to her mother. She never attended school because her mother Chapters 3–4: Poirot and Hastings search Mrs Ascher’s disapproved of it, and she was educated at home in a flat, where they find a pair of new stockings.