Masked Owl (Tasmanian)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tasmania 2018 Ian Merrill

Tasmania 2018 Ian Merrill Tasmania: 22nd January to 6th February Introduction: Where Separated from the Australian mainland by the 250km of water which forms the Bass Strait, Tasmania not only possesses a unique avifauna, but also a climate, landscape and character which are far removed from the remainder of the island continent. Once pre-trip research began, it was soon apparent that a full two weeks were required to do justice to this unique environment, and our oriGinal plans of incorporatinG a portion of south east Australia into our trip were abandoned. The following report summarises a two-week circuit of Tasmania, which was made with the aim of seeinG all island endemic and speciality bird species, but with a siGnificant focus on mammal watchinG and also enjoyinG the many outstandinG open spaces which this unique island destination has to offer. It is not written as a purely ornitholoGical report as I was accompanied by my larGely non-birdinG wife, Victoria, and as such the trip also took in numerous lonG hikes throuGh some stunninG landscapes, several siGhtseeinG forays and devoted ample time to samplinG the outstandinG food and drink for which the island is riGhtly famed. It is quite feasible to see all of Tasmania's endemic birds in just a couple of days, however it would be sacrilegious not to spend time savourinG some of the finest natural settinGs in the Antipodes, and enjoyinG what is arguably some of the most excitinG mammal watchinG on the planet. Our trip was huGely successful in achievinG the above Goals, recordinG all endemic birds, of which personal hiGhliGhts included Tasmanian Nativehen, Green Rosella, Tasmanian Boobook, four endemic honeyeaters and Forty-spotted Pardalote. -

Occupancy Patterns of an Apex Avian Predator Across a Forest Landscape

Austral Ecology (2020) , – Occupancy patterns of an apex avian predator across a forest landscape ADAM CISTERNE,*1 ROSS CRATES,1 PHIL BELL,2,3 ROB HEINSOHN1 AND DEJAN STOJANOVIC1 1Fenner School of Environment and Society, The Australian National University, Linnaeus Way, Acton, Canberra, Australian Capital Territory 2601 (Email: [email protected]); 2Department of State Growth, Forest Practices Authority; and 3School of Biological Sciences, The University of Tasmania, Hobart, Tasmania, Australia Abstract Apex predators are integral parts of every ecosystem, having top-down roles in food web mainte- nance. Understanding the environmental and habitat characteristics associated with predator occurrence is para- mount to conservation efforts. However, detecting top order predators can be difficult due to small population sizes and cryptic behaviour. The endangered Tasmanian masked owl (Tyto novaehollandiae castanops) is a noctur- nal predator with a distribution understood to be associated with high mature forest cover at broad scales. With the aim to gather monitoring data to inform future conservation effort, we trialled an occupancy survey design to model masked owl occurrence across ~800 km2 in the Tasmanian Southern Forests. We conducted 662 visits to assess masked owl occupancy at 160 sites during July–September 2018. Masked owl site occupancy was 12%, and estimated detectability was 0.26 (Æ0.06 SE). Cumulative detection probability of masked owls over four vis- its was 0.7. Occupancy modelling suggested owls were more likely to be detected when mean prey count was higher. However, low detection rates hindered the development of confident occupancy predictions. To inform effective conservation of the endangered Tasmanian masked owl, there is a need to develop novel survey tech- niques that better account for the ecology of this rare, wide-ranging and cryptic predator. -

Tasmanian Masked Owl)

The Minister included this species in the vulnerable category, effective from 19 August 2010 Advice to the Minister for Environment Protection, Heritage and the Arts from the Threatened Species Scientific Committee (the Committee) on Amendment to the list of Threatened Species under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act) 1. Reason for Conservation Assessment by the Committee This advice follows assessment of new information provided through the Species Information Partnership with Tasmania on: Tyto novaehollandiae castanops [Tasmanian population] (Tasmanian Masked Owl) 2. Summary of Species Details Taxonomy Conventionally accepted as Tyto novaehollandiae castanops (Gould, 1837; Higgins, 1999; Christidis and Boles, 2008). There are three other subspecies of Tyto novaehollandiae which occur within Australia. Tyto novaehollandiae novaehollandiae occurs in southeast Queensland, eastern New South Wales, Victoria, southern South Australia and southern Western Australia. Tyto novaehollandiae kimberli is listed as vulnerable under the EPBC Act and occurs in northeast Queensland, the Northern Territory and northeast Western Australia. Tyto novaehollandiae melvillensis is listed as endangered under the EPBC Act and occurs on Melville Island and Bathurst Island (Higgins, 1999; DPIPWE, 2009). State Listing Status Listed as endangered under the Tasmanian Threatened Species Protection Act 1995. Description A large owl, weighing up to 1260 g, with a wingspan of up to 128 cm. Females are larger and heavier than males and considerably darker. The upperparts of this subspecies are dark brown to light chestnut in colour, with white speckling. The prominent facial disc is buff to chestnut coloured, with a darker margin, and chestnut coloured shading around the eyes. The legs are fully feathered and the feet are powerful with long talons (Higgins, 1999). -

5Th Australasian Ornithological Conference 2009 Armidale, NSW

5th Australasian Ornithological Conference 2009 Armidale, NSW Birds and People Symposium Plenary Talk The Value of Volunteers: the experience of the British Trust for Ornithology Jeremy J. D. Greenwood, Centre for Research into Ecological and Environmental Modelling, The Observatory, Buchanan Gardens, University of St Andrews, Fife KY16 9LZ, Scotland, [email protected] The BTO is an independent voluntary body that conducts research in field ornithology, using a partnership between amateurs and professionals, the former making up the overwhelming majority of its c13,500 members. The Trust undertakes the majority of the bird census work in Britain and it runs the national banding and the nest records schemes. The resultant data are used in a program of monitoring Britain's birds and for demographic analyses. It runs special programs on the birds of wetlands and of gardens and has undertaken a series of distribution atlases and many projects on particular topics. While independent of conservation bodies, both voluntary and statutory, much of its work involves the provision of scientific evidence and advice on priority issues in bird conservation. Particular recent foci have been climate change, farmland birds (most of which have declined) and woodland birds (many declining); work on species that winter in Africa (many also declining) is now under way. In my talk I shall describe not only the science undertaken by the Trust but also how the fruitful collaboration of amateurs and professionals works, based on their complementary roles in a true partnership, with the members being the "owners" of the Trust and the staff being responsible for managing the work. -

December 06 Book.Pmd

186 AUSTRALIAN FIELD ORNITHOLOGY 2006, 23, 186–191 Prey Partitioning and Behaviour of Breeding Masked Owls Tyto novaehollandiae on the Central Coast of New South Wales MICHAEL TODD 187 Excelsior Parade, Toronto, New South Wales 2283 (Email: [email protected]) Summary Masked Owls Tyto novaehollandiae were observed at a nest that successfully fledged two owlets near Newcastle, central coastal New South Wales, over winter 2005. The nest was situated in bushland supporting native mammal species. The female Owl was observed to bring Bush Rats Rattus fuscipes (n = 3) and a Petaurus glider to the nest. In contrast, the male brought only smaller prey including the Brown Antechinus Antechinus stuartii (n = 3) and House Mouse Mus domesticus (n = 3). The combined feeding rate in the second half of the nestling period, when the female Owl was hunting, was 1.2 items/h (n = 13.1 h) in the evenings. Introduction Although the diet of the Masked Owl Tyto novaehollandiae has been examined in several areas of mainland Australia and Tasmania, most of these studies have been of regurgitated pellets rather than direct observations of captured prey (summarised by Higgins 1999; later studies by Kavanagh 2002 and McNabb et al. 2003). The Masked Owl exhibits strong reversed sexual size dimorphism (female 30% heavier than male: Higgins 1999), especially in the Tasmanian subspecies T.n. castanops in which the sexes take different-sized prey (prey of male averages 97 g, of female 261 g). The larger female Owl takes prey as large as European Rabbits Oryctolagus cuniculus (Mooney 1993). There are limited observations of such prey partitioning on the Australian mainland. -

Ecology and Habitat of a Threatened Nocturnal Bird, the Tasmanian Masked Owl

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Tasmania Open Access Repository Ecology and habitat of a threatened nocturnal bird, the Tasmanian Masked Owl By Michael Kenneth Todd B.Sc.(Hons), University of Newcastle Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Tasmania Hobart, Tasmania, Australia August 2012 1 Ecology of the Tasmanian Masked Owl Declarations This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for a degree or diploma in any university or other institution. This thesis, to the best of my knowledge, contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due acknowledgment is made in the text. This thesis may be available for loan and limited copying in accordance with the Copyright Act of 1968. The research associated with this thesis abides by the international and Australian codes on human and animal experimentation, the guidelines by the Australian Government's Office of the Gene Technology Regulator and the rulings of the Safety, Ethics and Institutional Biosafety Committees of the University. All research conducted was under valid animal ethics approvals. Relevant permits were obtained from the Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment and the University of Tasmania Animal Ethics Committee (A0009763 and A0009685). Michael Kenneth Todd 2 Ecology of the Tasmanian Masked Owl Dedication: This thesis is dedicated to the marvelously mysterious Tasmanian Masked Owl. May they continue to haunt Tasmania’s forests. “Once the sun disappears, along with the light, She stretches her wings and sets off in flight, And hunts far and wide well into the night, Small native mammals her especial delight; She’s endangered!” From “The Masked Owl” -Philip R. -

Trainee Bander's Diary (PDF

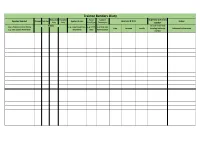

Trainee Banders Diary Extracted Handled Band Capture Supervising A-Class Species banded Banded Retraps Species Groups Location & Date Notes Only Only Size/Type Techniques Bander Totals Include name and Use CAVS & Common Name e.g. Large Passerines, e.g. 01AY, e.g. Mist-net, Date Location Locode Banding Authority Additional information e.g. 529: Superb Fairy-wren Shorebirds 09SS Hand Capture number Reference Lists 05 SS 10 AM 06 SS 11 AM Species Groups 07 SS 1 (BAT) Small Passerines 08 SS 2 (BAT) Large Passerines 09 SS 3 (BAT) Seabirds 10 SS Shorebirds 11 SS Species Parrots and Cockatoos 12 SS 6: Orange-footed Scrubfowl Gulls and Terns 13 SS 7: Malleefowl Pigeons and Doves 14 SS 8: Australian Brush-turkey Raptors 15 SS 9: Stubble Quail Waterbirds 16 SS 10: Brown Quail Fruit bats 17 SS 11: Tasmanian Quail Ordinary bats 20 SS 12: King Quail Other 21 SS 13: Red-backed Button-quail 22 SS 14: Painted Button-quail Trapping Methods 23 SS 15: Chestnut-backed Button-quail Mist-net 24 SS 16: Buff-breasted Button-quail By Hand 25 SS 17: Black-breasted Button-quail Hand-held Net 27 SS 18: Little Button-quail Cannon-net 28 SS 19: Red-chested Button-quail Cage Trap 31 SS 20: Plains-wanderer Funnel Trap 32 SS 21: Rose-crowned Fruit-Dove Clap Trap 33 SS 23: Superb Fruit-Dove Bal-chatri 34 SS 24: Banded Fruit-Dove Noose Carpet 35 SS 25: Wompoo Fruit-Dove Phutt-net 36 SS 26: Pied Imperial-Pigeon Rehabiliated 37 SS 27: Topknot Pigeon Harp trap 38 SS 28: White-headed Pigeon 39 SS 29: Brown Cuckoo-Dove Band Size 03 IN 30: Peaceful Dove 01 AY 04 IN 31: Diamond -

Ecology and Habitat of a Threatened Nocturnal Bird, the Tasmanian Masked Owl

Ecology and habitat of a threatened nocturnal bird, the Tasmanian Masked Owl By Michael Kenneth Todd B.Sc.(Hons), University of Newcastle Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Tasmania Hobart, Tasmania, Australia August 2012 1 Ecology of the Tasmanian Masked Owl Declarations This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for a degree or diploma in any university or other institution. This thesis, to the best of my knowledge, contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due acknowledgment is made in the text. This thesis may be available for loan and limited copying in accordance with the Copyright Act of 1968. The research associated with this thesis abides by the international and Australian codes on human and animal experimentation, the guidelines by the Australian Government's Office of the Gene Technology Regulator and the rulings of the Safety, Ethics and Institutional Biosafety Committees of the University. All research conducted was under valid animal ethics approvals. Relevant permits were obtained from the Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment and the University of Tasmania Animal Ethics Committee (A0009763 and A0009685). Michael Kenneth Todd 2 Ecology of the Tasmanian Masked Owl Dedication: This thesis is dedicated to the marvelously mysterious Tasmanian Masked Owl. May they continue to haunt Tasmania’s forests. “Once the sun disappears, along with the light, She stretches her wings and sets off in flight, And hunts far and wide well into the night, Small native mammals her especial delight; She’s endangered!” From “The Masked Owl” -Philip R. -

Southern Australia Including Tasmania

Stunningly close roosting Letter-winged Kites were one of many huge highlights on this year’s tour (Simon Mitchell). SOUTHERN AUSTRALIA INCLUDING TASMANIA 11 OCTOBER – 2 NOVEMBER 2015 LEADERS: SIMON MITCHELL, CRAIG ROBSON and FRANK LAMBERT 1 BirdQuest Tour Report: Southern Australia & Tasmania www.birdquest-tours.com Plains Wanderers performed exceptionally well and were nominated bird of the trip (Simon Mitchell). First time visitors to Australia heading there for birding trips seem to return from their travels with one common sentiment: The continent is an almost criminally underrated birding destination. Perhaps, since there is little crossover with Palearctic and Nearctic species it’s avifauna remains ‘off the radar’ of many European and American birders. However, it’s incredible the variety of habitats, climates, genera and different types of birding the on the Southern Australian loop matches anything in even the most diverse parts of South America, Africa and Asia have to offer. The contrasts between biomes and avifaunal communities in such a short space of time was quite staggering. In the damp temperate rainforests, we found Superb Lyrebirds, Pilotbirds, Eastern Whipbirds and a variety of brightly coloured and very tame robin species. Along the sandy beaches open pastures of Phillip Island we found Cape Barren Geese, Hooded Dotterels and Little Penguins and rocky shores near Adelaide held Sooty and Australian Pied Oystercatchers. The montane heaths held Southern Emu-wrens, Striated Fieldwren, Chestnut-rumped Heathwren and White-eared Honeyeaters. Dry mallee forests further inland held a variety of Honeyeaters as well as difficult target birds such as Striated Grasswren, Mallee Emu-wren, Hooded Robin, Chestnut-backed Quail-thrush, Crested Bellbird and Gilbert’s Whistler. -

Ecology and Habitat of a Threatened Nocturnal Bird, the Tasmanian Masked Owl

Ecology and habitat of a threatened nocturnal bird, the Tasmanian Masked Owl By Michael Kenneth Todd B.Sc.(Hons), University of Newcastle Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Tasmania Hobart, Tasmania, Australia August 2012 1 Ecology of the Tasmanian Masked Owl Declarations This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for a degree or diploma in any university or other institution. This thesis, to the best of my knowledge, contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due acknowledgment is made in the text. This thesis may be available for loan and limited copying in accordance with the Copyright Act of 1968. The research associated with this thesis abides by the international and Australian codes on human and animal experimentation, the guidelines by the Australian Government's Office of the Gene Technology Regulator and the rulings of the Safety, Ethics and Institutional Biosafety Committees of the University. All research conducted was under valid animal ethics approvals. Relevant permits were obtained from the Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment and the University of Tasmania Animal Ethics Committee (A0009763 and A0009685). Michael Kenneth Todd 2 Ecology of the Tasmanian Masked Owl Dedication: This thesis is dedicated to the marvelously mysterious Tasmanian Masked Owl. May they continue to haunt Tasmania’s forests. “Once the sun disappears, along with the light, She stretches her wings and sets off in flight, And hunts far and wide well into the night, Small native mammals her especial delight; She’s endangered!” From “The Masked Owl” -Philip R. -

YELLOW THROAT the Newsletter of Birdlife Tasmania: a Branch of Birdlife Australia Number 112, Summer 2020

YELLOW THROAT The newsletter of BirdLife Tasmania: a branch of BirdLife Australia Number 112, Summer 2020 Welcome to all our new members to the Summer edi- Contents in this issue tion of Yellow Throat. Can technology save our migratory shorebirds?..........2 This issue has many articles and observations of great Why have Bar-tailed Godwits numbers in Tasmania in- general interest. The focus is on waders because the creased this summer?...................................................5 northern Wader Forum is coming up in January, and we Pardalote observations at Peter Murrell Reserves …….6 hope to whet your appetite to attend. The first article is Are vagrant migratory shorebirds lost?........................7 by guest writer Ken Gosbell from the Victorian Wader Looking for banded lapwings…………………………………....9 Studies Group, who writes about tracking technology and how it is helping us understand migration ques- Birdata update— some exciting developments…..…..10 tions. This is followed by two thought-provoking articles Birding and caretaking on Maatsuyker Island……….....12 by Mike Newman: firstly, investigating why observa- The Nest……………………………………………………….………...13 tions of Bar-tailed Godwits have increased in summer in Pallid Cuckoo project round up…………………………..…..14 Tasmania; and, secondly, questioning the occurrence of vagrant migratory shorebirds. Birdata continues to Recent observations from Austins Ferry ... 16 develop excitingly, and this edition tells you more! Raptor Rhymes…………………………………………………….….17 Outings have continued with Covid-19 safety measures BirdLife Tasmania news and views in place. Three are reported on, including Maria Island Conservation report……………………………..19 on 22 November, which recorded 54 bird species, AGM notice……………………….………………...20 ensuring everyone had a great day. Outing reports……………………...……………..20 The AGM is coming up in March, and this issue holds all Media releases……………………… ..………….24 relevant information. -

Risks of Anticoagulant Rodenticides to Tasmanian Raptors

Risks of anticoagulant rodenticides to Tasmanian raptors Nick Mooney, PO Box 120, Richinond 7025, [email protected]. Background First generation anticoagulant rodenticides (FGARs) Wildlife is subject to all manner of anthropogenic with warfarin or coumatetralyl as the active ingredient hazards, even in wilderness areas where persistent (e.g. Ratsak Double Strength and Racumin respectively) chemicals and feral species can intrude, and where are pesticides with a short duration of action (and people visit, bringing, at the minimum, risks of disease, require ingestion over a long period of time (i.e. behavioural disruption, physical and chemical pollution, multiple doses) to be fatal. In comparison, second gener and accidents such as collisions. In less remote places ation anticoagulant rodenticides (SGARs, developed such hazards seem greater and typically include because effectiveness of some FGARs was reducing) interactions with pets, more people, infrastructure and with active ingredient brodifacoum (e.g. Talon and chemicals, including pesticides. The latter is a reason Ratsak Fast Action) usually only require single doses to ably well-recorded hazard to wildlife, but most concern kill and have a long duration of action, i.e. an animal usually relates to agricultural and forestry areas. that has had a lethal dose takes longer to die. Some However, use of chemicals in urban landscapes also has rodenticide brands (e.g. Ratsak) produce both FGAR great potential to affect wildlife. and SGAR products, the former advertised as present One of the oldest settled human and animal inter ing less of a secondary poisoning risk: actions is that with rodents, usually the Brown Rat, Rattus (www.ratsak.com.au/faqs).