Page 1 J S T O M a T O L O G Y E D U J O U R N a L VOLUME 3 ISSUE 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lista Copiilor Admiși an Școlar 2021-2022

Lista copiilor admiși An școlar 2021-2022 LICEUL „MATHIAS HAMMER“ ANINA - Limba română - Tradițional ANINA - CARAŞ-SEVERIN Nr. crt. Nume Prenume Etapa 1 BIVOLARIU LARISA DARIA I 2 BORCEAN MARIA CRISTINA I 3 CÂRSTEA DRAGOȘ DARIUS VALENTIN I 4 CRĂCIUN FABIAN I 5 CRĂCIUN YANNIS I 6 DIACONU ANTONIA MIRIAM I 7 DIACONU COSMIN GABRIEL I 8 DRUMAȘ DARIUS CONSTANTIN I 9 DUMITRACHE PAVEL TEODOR I 10 FARAGO SAMYA SORINA I 11 HANZI DAVID GABRIEL I 12 HLINA MAIA IZABELA I 13 HURMUZACHE GIULIA FLAVIA I 14 KONCZ FLORIN CRISTIAN I 15 KOVACS NAOMI MIRUNA I 16 MOLIN PAULA ANAMARIA I 17 MUNTEANU DARIUS CASIAN ANDREI I 18 NEBILIAC IOAN I 19 NERGEȘ MIRIAM I 20 OLTEANU IASMINA ALISS I 21 PODEAN DENISA IOANA I 22 SCHINTEIE MAIA ȘTEFANIA IONELA I 23 STERIE DARIUS I 24 TRIȘCĂ ANDREI DANIEL I 25 TUDOR MARIA ELISABETA I 26 VENCZEL ANAIS MARIA I Pagina 1 / 102 ŞCOALA GIMNAZIALĂ ARMENIŞ - Limba română - Tradițional ARMENIŞ - CARAŞ-SEVERIN Nr. crt. Nume Prenume Etapa 1 ARDELEAN RĂZVAN-MIHAI I 2 CARAIMAN MATIAS I 3 DRAGOMIR FLORIN-CĂTĂLIN I 4 GODEAN GEORGE I 5 HURDUZEU IONUȚ CRISTIAN I 6 MICULESCU IONUȚ-DARIUS I 7 NICOLICEA IULIANA TITIANA I Pagina 2 / 102 LICEUL "HERCULES" BAILE HERCULANE - Limba română - Tradițional BĂILE HERCULANE - CARAŞ-SEVERIN Nr. crt. Nume Prenume Etapa 1 BÎRLAN PATRIK IOAN I 2 BOȚOACĂ PATRICK CHRISTIAN I 3 CORNEANU KARINA NICOLE I 4 CUCERCA MARCO CRISTIAN I 5 FRUMOSU ANAMARIA JULIE I 6 GRUND ANDRADA CRISTINA I 7 MARCEA NICOLAS IOACHIM I 8 MARINESCU IONELA REBECA CRISTIANA I 9 MIHAȘCA BIANCA I 10 MOATER DRAGOȘ I 11 NICA OLIVIA FLORINA I 12 PAPAVĂ ALEXANDRU MARIAN I 13 PAPICI DAISA MARIA I 14 PĂSĂRIN HORAȚIU ANDREI I 15 PENEȘEL CONSTANTIN NICOLAE I 16 POPESCU TIBERIU CRISTIAN I 17 ROMAN ROBERT I 18 SITARIU ANDREAS RĂZVAN I 19 STOICA-PREDESCU LARA MARIA I 20 STROIȚA DUMITRU I 21 ȘANDRU-UNTARU MAYA I 22 ȘULMA ROXANA MARIANA I 23 TELEAGĂ IOANA ANTONIA I Pagina 3 / 102 ŞCOALA GIMNAZIALĂ BĂNIA - Limba română - Tradițional BĂNIA - CARAŞ-SEVERIN Nr. -

Ryerson University Spring Graduates

Ryerson University Spring Graduates June 2020 Faculty of Arts 2 Faculty of Communication & Design 11 Faculty of Community Services 21 Faculty of Engineering and Architectural Science 35 Faculty of Science 46 Ted Rogers School of Management 54 Yeates School of Graduate Studies 71 The G. Raymond Chang School of Continuing Education 73 Faculty of Arts Pamela Sugiman Dean Faculty of Arts Janice Fukakusa Chancellor Mohamed Lachemi President and Vice-Chancellor Charmaine Hack Registrar Ryerson Gold Medal Presented to Mayah Obadia Geographic Analysis 2 Faculty of Arts Undergraduate Degree Programs Arts and Contemporary Studies Bachelor of Arts (Honours) *Diana Abo Harmouch Carmen Jajjo *Megumi Noteboom *Sima Rebecca Abrams Leya Jasat Valentina Padure Qeyam Amiri Sophie Johnson *Naiomi Marcia Perera Brodie Barrick Babina Kamalanathan Charlotte Jane Prokopec Rebecca Claire Chen Caroline Susan Kewley Regan Reynolds Erin Tanya Clarke Jessica Laurenza Joshua Ricci *Megan Lisa Devoe Claire Lowenstein Kaitlin Anganie Seepersaud *Manpreet Kaur Dhaliwal *Avigayil Margolis Gabriela Skwarko Tatum Lynn Donovan Sara McArthur Julia Macey Sullivan Faith Raha Giahi *Nadia Celeste McNairn *Helen Gillian Webb Meagan Gove *Mahbod Mehrvarz *Michael Worbanski Salem Habtom Andrew Moon Smyrna Wright *William Hanchar *Liana Gabriella Mortin Calum Jacques Potoula Mozas Criminology Bachelor of Arts (Honours) *Annabelle Adjei *Jenna Anne Giannini Veronica Hiu Lam Lee Stanislav Babinets Albina Glatman Karishma Catherine Lutchman Hela Bakhtari Farah Khaled Gregni Simbiat -

Names in Multi-Lingual, -Cultural and -Ethic Contact

Oliviu Felecan, Romania 399 Romanian-Ukrainian Connections in the Anthroponymy of the Northwestern Part of Romania Oliviu Felecan Romania Abstract The first contacts between Romance speakers and the Slavic people took place between the 7th and the 11th centuries both to the North and to the South of the Danube. These contacts continued through the centuries till now. This paper approaches the Romanian – Ukrainian connection from the perspective of the contemporary names given in the Northwestern part of Romania. The linguistic contact is very significant in regions like Maramureş and Bukovina. We have chosen to study the Maramureş area, as its ethnic composition is a very appropriate starting point for our research. The unity or the coherence in the field of anthroponymy in any of the pilot localities may be the result of the multiculturalism that is typical for the Central European area, a phenomenon that is fairly reflected at the linguistic and onomastic level. Several languages are used simultaneously, and people sometimes mix words so that speakers of different ethnic origins can send a message and make themselves understood in a better way. At the same time, there are common first names (Adrian, Ana, Daniel, Florin, Gheorghe, Maria, Mihai, Ştefan) and others borrowed from English (Brian Ronald, Johny, Nicolas, Richard, Ray), Romance languages (Alessandro, Daniele, Anne, Marie, Carlos, Miguel, Joao), German (Adolf, Michaela), and other languages. *** The first contacts between the Romance natives and the Slavic people took place between the 7th and the 11th centuries both to the North and to the South of the Danube. As a result, some words from all the fields of onomasiology were borrowed, and the phonological system was changed, once the consonants h, j and z entered the language. -

State of Delaware

State of Delaware Department of Elections Permanent Absentee Voter List Voter Information First Name Middle Name Last Name County GARY LEE BENSINGER SUSSEX EDNA AARON KENT JOHN A AARON NEW CASTLE THOMAS A AARON KENT VERA JEAN AARON NEW CASTLE HOWARD LEONARD ABARE SUSSEX SALLY A ABARE SUSSEX PETER ROBERT ABATE KENT JESSICA LEIGH ABBEY NEW CASTLE BARBARA R ABBOTT SUSSEX BRUCE ALLEN ABBOTT NEW CASTLE CAROL E ABBOTT KENT ELIZABETH CARRIE ABBOTT KENT JANICE M ABBOTT KENT JO ANN ABBOTT KENT JOHN S ABBOTT SUSSEX JUDITH ANN ABBOTT KENT KARLA W ABBOTT SUSSEX SHARON L ABBOTT SUSSEX KAREN M ABDALA SUSSEX KHADIRA NAEEMA ABDUL-AZIZ KENT KHALIL ABDUL-MAJID NEW CASTLE AHMAD J ABDULLAH NEW CASTLE ALMESHIA ZAHIR ABDULLAH NEW CASTLE MICAH YUSEF ABDULLAH NEW CASTLE YASMEEN ABDULLAH NEW CASTLE ARTHUR ELVAN ABEL SUSSEX DIANE CLAIRE ABEL KENT GERTRUDE E ABEL NEW CASTLE JOANNE ABEL NEW CASTLE JOSEPH MILBURN ABELL SUSSEX SALLIE HEINRICHS ABELL SUSSEX NAWAL A ABOU-RAHME NEW CASTLE RAJA W ABOU-RAHME NEW CASTLE DOROTHY MARIE ABRAHAM KENT LISA SIEGEL ABRAHAMSON SUSSEX CHRISTINA ABRAMOWICZ SUSSEX CAITLIN NICOLE ABRAMS SUSSEX DOROTHY E ABRAMS NEW CASTLE MARILYN NASHMAN ABRAMS NEW CASTLE NOELLY RAPHAELLI ABREU NEW CASTLE IRA L ABSHER SUSSEX JAY L ABSHER SUSSEX LINDA K ABSHER SUSSEX SHIRLEY A ABSHER SUSSEX TREVA GAIL ABSHER SUSSEX HANAA M ABUELELA NEW CASTLE ELIZABETH MILIANA ABUSCHINOW SUSSEX SANDSHA ABUSCHINOW SUSSEX GWEN MARY ACCARDI KENT CLAUDIA E ACERO LUNA NEW CASTLE HELEN M ACHENBACH NEW CASTLE DOLORES ACKER SUSSEX EDWIN JOHN ACKER NEW CASTLE LEWIS D ACKER SUSSEX -

See Who Attended

Company Name First Name Last Name Job Title Country 24Sea Gert De Sitter Owner Belgium 2EN S.A. George Droukas Data analyst Greece 2EN S.A. Yannis Panourgias Managing Director Greece 3E Geert Palmers CEO Belgium 3E Baris Adiloglu Technical Manager Belgium 3E David Schillebeeckx Wind Analyst Belgium 3E Grégoire Leroy Product Manager Wind Resource Modelling Belgium 3E Rogelio Avendaño Reyes Regional Manager Belgium 3E Luc Dewilde Senior Business Developer Belgium 3E Luis Ferreira Wind Consultant Belgium 3E Grégory Ignace Senior Wind Consultant Belgium 3E Romain Willaime Sales Manager Belgium 3E Santiago Estrada Sales Team Manager Belgium 3E Thomas De Vylder Marketing & Communication Manager Belgium 4C Offshore Ltd. Tom Russell Press Coordinator United Kingdom 4C Offshore Ltd. Lauren Anderson United Kingdom 4Cast GmbH & Co. KG Horst Bidiak Senior Product Manager Germany 4Subsea Berit Scharff VP Offshore Wind Norway 8.2 Consulting AG Bruno Allain Président / CEO Germany 8.2 Consulting AG Antoine Ancelin Commercial employee Germany 8.2 Monitoring GmbH Bernd Hoering Managing Director Germany A Word About Wind Zoe Wicker Client Services Manager United Kingdom A Word About Wind Richard Heap Editor-in-Chief United Kingdom AAGES Antonio Esteban Garmendia Director - Business Development Spain ABB Sofia Sauvageot Global Account Executive France ABB Jesús Illana Account Manager Spain ABB Miguel Angel Sanchis Ferri Senior Product Manager Spain ABB Antoni Carrera Group Account Manager Spain ABB Luis andres Arismendi Gomez Segment Marketing Manager Spain -

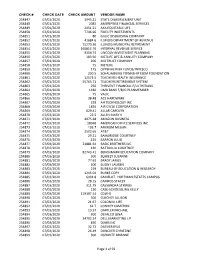

2020-2021 Check Register

CHECK # CHECK DATE CHECK AMOUNT VENDOR NAME 254847 07/01/2020 1945.21 STATE DISBURSEMENT UNIT 254848 07/01/2020 2083 AMERIPRISE FINANCIAL SERVICES 254849 07/01/2020 2451.21 AXA EQUITABLE LIFE 254850 07/01/2020 7746.96 FIDELITY INVESTMENTS 254851 07/01/2020 80 GALIC DISBURSING COMPANY 254852 07/01/2020 41684.6 ILLINOIS DEPARTMENT OF REVENUE 254853 07/01/2020 75270.36 ILLINOIS MUNICIPAL RETIREMENT 254854 07/01/2020 160815.76 INTERNAL REVENUE SERVICE 254855 07/01/2020 9354.74 LINCOLN INVESTMENT PLANNING 254856 07/01/2020 183.56 METLIFE LIFE & ANNUITY COMPANY 254857 07/01/2020 200 MG TRUST COMPANY 254858 07/01/2020 75 METLIFE 254859 07/01/2020 175 OPPENHEIMER FUNDS/INVESCO 254860 07/01/2020 230.5 SCHAUMBURG TOWNSHIP ELEM FOUNDATION 254861 07/01/2020 12573.5 TEACHERS HEALTH INSURANCE 254862 07/01/2020 55765.71 TEACHERS RETIREMENT SYSTEM 254863 07/01/2020 250 THRIVENT FINANCIAL F/LUTHERANS 254864 07/01/2020 1330 UMB BANK F/B/O PLANMEMBER 254865 07/01/2020 75 VALIC 254866 07/03/2020 38.48 ACE HARDWARE 254867 07/03/2020 228 AH TECHNOLOGY INC 254868 07/03/2020 1826 AIR CYCLE CORPORATION 254869 07/03/2020 629.41 ALLAR CAROLYN 254870 07/03/2020 22.5 ALLEN MARY K 254871 07/03/2020 4075.28 AMAZON BUSINESS 254872 07/03/2020 18048 AMERICAN OFFICE SERVICES INC 254873 07/03/2020 103.7 ANKROM MEGAN 254874 07/03/2020 3502.65 AT&T 254875 07/03/2020 29.21 BAINBRIDGE COURTNEY 254876 07/03/2020 125 BARRON JULIO 254877 07/03/2020 21881.64 BASIC BROTHERS INC 254878 07/03/2020 130 BATTAGLIA COURTNEY 254879 07/03/2020 82743.41 BENCHMARK EDUCATION COMPANY 254880 -

Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Malta

DIPLOMATIC LIST 2017 State Protocol D I P L O M A T I C L I S T Including International Organizations and other Representations to Albania STATE PROTOCOL 1 DIPLOMATIC LIST 2017 State Protocol CONTENTS Page 1. Diplomatic Missions 3 - 133 2. International Organisations and other Representations 134 - 146 3. Honorary Consuls 147 - 153 4. National Days 154 - 159 TIRANA – ALBANIA February 2017 DIPLOMATIC LIST Published by STATE PROTOCOL DEPARTMENT Ministria e Punëve të Jashtme, Republika e Shqipërisë Postal Address: Bulevardi Zhan d’Ark, Nr 6, Tiranë, Shqipëri Tel: +355 4 23 64 090 (ext: 79 205) Fax: +355 4 23 62 084 / 85 Email: [email protected] Web: www.mfa.gov.al 2 DIPLOMATIC LIST 2017 State Protocol DIPLOMATIC MISSIONS 3 DIPLOMATIC LIST 2017 State Protocol AFGANISTAN EMBASSY OF AFGANISTAN Chancery: Sofia, Bulgaria National Day: ______________________________________________________________________________________ His Excellency Mr. Sialluah MAHMUD Agree Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary 4 DIPLOMATIC LIST 2017 State Protocol ALGERIA EMBASSY OF PEOPLE’S DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF ALGERIA Chancery: 14A, Vassileos Konstantinou Ave, 116 35, Athens, Greece Tel: (+30) 210 7564191-2 Fax: (+30) 210 7018681-2 Office of the Ambassador: (+30) 210 7564193 Fax: (+30) 210 7562450 E-mail: [email protected] National Day: November 1st ________________________________________________________________________ His Excellency Mr. Noureddine BARDAD-DAIDJ 10.11.2016 Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary Mr. Naim SOLTANE CHAIBOUT Counsellor Mrs. Rachida SOLTANE CHAIBOUT Mr. Atmane KISSOUM Third Secretary Mr. Mohamed LABRI Atache Mrs. Hafida LABRI Mr. Rachid BOUREKOUA Attache (Consular Affairs) Mr. Rachid HANIFI Attache (Consular Affairs) Mrs. Rafika HANIFI Mrs. Souhaila BOUREKOUA Attache (Press) DIPLOMATIC OFFICE IN TIRANA Chancellery: Str. -

2019-20 Atlantic 10 Commissioner's Honor Roll

2019-20 Atlantic 10 Commissioner’s Honor Roll Name Sport Year Hometown Previous School Major DAVIDSON Alexa Abele Women's Tennis Senior Lakewood Ranch, FL Sycamore High School Economics Natalie Abernathy Women's Cross Country/Track & Field First Year Student Land O Lakes, FL Land O Lakes High School Undecided Cameron Abernethy Men's Soccer First Year Student Cary, NC Cary Academy Undecided Alex Ackerman Men's Cross Country/Track & Field Sophomore Princeton, NJ Princeton High School Computer Science Sophia Ackerman Women's Track & Field Sophomore Fort Myers, FL Canterbury School Undecided Nico Agosta Men's Cross Country/Track & Field Sophomore Harvard, MA F W Parker Essential School Undecided Lauryn Albold Women's Volleyball Sophomore Saint Augustine, FL Allen D Nease High School Psychology Emma Alitz Women's Soccer Junior Charlottesville, VA James I Oneill High School Psychology Mateo Alzate-Rodrigo Men's Soccer Sophomore Huntington, NY Huntington High School Undecided Dylan Ameres Men's Indoor Track First Year Student Quogue, NY Chaminade High School Undecided Iain Anderson Men's Cross Country/Track & Field Junior Helena, MT Helena High School English Bryce Anthony Men's Indoor Track First Year Student Greensboro, NC Ragsdale High School Undecided Shayne Antolini Women's Lacrosse Senior Babylon, NY Babylon Jr Sr High School Political Science Chloe Appleby Women's Field Hockey Sophomore Charlotte, NC Providence Day School English Lauren Arkell Women's Lacrosse Sophomore Brentwood, NH Phillips Exeter Academy Physics Sam Armas Women's Tennis -

01087-130520.Pdf

First Name Last Name Zip State Organization Comment Paul Franzmann WA 'Deliberately misleading' should not be considered aveat emptor. A few years back, I paid top dollar for a queen-size organic mattress, or so I thought. Today I find out that it could be made from just about anything, and I am left wondering if I got the shaft. Please work to ensure that the organic label means what it says, that it's ingredients and production are clean and clear of any material or process that is Anne Huibregtse NY damaging to me or the earth we all depend on for all our needs. Charles Jameson GA A lie is a lie. Don't let companies lie about what is in their products. cat montoya CO absurd Lee McCarthy MI Act to prevent fraud. No more excuses! Allowing companies to use the label "organic" without restriction amounts to fraud. The Kathy Freeman FL FTC should protect consumers from being misled. Carmie Alvaro also where food is concerned I'm very much in question of what is packaged in China J. Wackowski IN Another eg of govt failure to protect its citizens in deference to corp overlords. Any food label with the word "Organic" on it, should TRULY be 100% organic (and not David Zaccagnino CA contain any GMO ingredients)!!!!! As a family trying to eat organic, we definitely want to be sure that our food is pesticide Gail Graff CA free. Everyone should have pesticide free food. As a former organic farmer I wish to see all organic products remain ORGANIC ! That is Walt Reaster TN what people want ! As a Master's student working towards a holistic health degree, I see everyday the importance of having a healthier diet and lifestyle, not just our food anymore. -

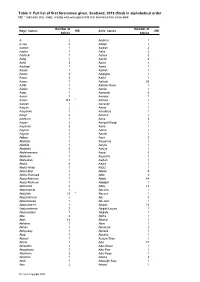

Table 4: Full List of First Forenames Given, Scotland, 2019 (Final) In

Table 4: Full list of first forenames given, Scotland, 2019 (final) in alphabetical order NB: * indicates that, sadly, a baby who was given that first forename has since died. Number of Number of Boys' names NB Girls' names NB babies babies A 2 Aadhira 1 A-Jay 2 Aadya 1 Aadam 1 Aaidah 2 Aaden 1 Aaila 2 Aadhvik 1 Aaima 3 Aafiq 1 Aairah 2 Aahil 3 Aaiva 1 Aanhad 1 Aalea 1 Aansh 1 Aaleah 1 Aaran 3 Aaleigha 1 Aarav 3 Aalifa 1 Aaren 1 Aaliyah 25 Aarib 1 Aaliyah-Rose 1 Aarish 1 Aamie 1 Aariz 1 Aaminah 2 Aaroh 1 Aamiya 1 Aaron 143 * Aamna 1 Aarush 1 Aaneyah 1 Aaryan 2 Aania 1 Aaryansh 1 Aaradhya 1 Aaryn 2 Aarchie 1 Aathiran 1 Aaria 3 Aayan 2 Aariyah-Reign 1 Aayansh 3 Aarla 1 Aaycen 1 Aarna 1 Aayush 1 Aaruhi 1 Abbas 1 Aarvi 2 Abdalah 1 Aaryanna 1 Abdalla 1 Aaryia 1 Abdallah 3 Aasiya 1 Abdelmoneim 1 Aayat 5 Abdoulie 1 Aayesha 1 Abduallah 1 Aaylah 1 Abdul 8 Aayra 1 Abdul-Ahad 1 Aaziz 1 Abdul-Bari 1 Abbey 5 Abdul-Hameed 1 Abbi 2 Abdul-Mannan 1 Abbie 44 Abdul-Rahman 1 Abbigail 1 Abdulaziz 2 Abby 13 Abdulhamid 1 Abeeha 1 Abdullah 13 * Abeera 1 Abdulrahman 2 Abi 5 Abdulrazzaq 1 Abi-Gail 1 Abduraheem 1 Abigail 73 Abdurrahman 2 Abigail-Louise 1 Abdussalam 1 Abigale 1 Abe 3 Abiha 1 Abel 14 Abisha 1 Abhainn 1 Abra 1 Abhav 1 Abrianna 2 Abhyuday 1 Abrielle 1 Abid 1 Absalat 1 Abinav 1 Acacia-Skye 1 Abiral 1 Ada 77 Abiselom 1 Ada-Grace 1 Aboubacar 1 Ada-Rae 1 Abraham 3 Ada-Rose 1 Abrahim 1 Adaira 2 Abtin 1 Adaleigh-May 1 Abu 2 Adalet 1 © Crown Copyright 2020 Table 4: Continued NB: * indicates that, sadly, a baby who was given that first forename has since died. -

28^ Graduatoria in Ordine Di Punteggio

28° Graduatoria per l'accesso agli alloggi di erp in ordine di punteggio POSI DATA ZION COGNOME NOME TOT DOMANDA E 0,00 1 28/12/15 EBIANGON NKOT DIANE ROMANCE 36,00 2 29/07/15 VALENTINO VALENTINA 34,00 3 24/08/15 IQBAL RAHIL JAVED 32,00 4 22/12/15 BIRTEA MARIANA DANIELA 32,00 5 04/09/14 ENUNNEKU JUDITH 30,50 6 01/10/14 DABO LUBJANA 30,50 7 18/12/14 SISIANU ION 30,50 8 18/09/14 ALBERTI MARCO 30,00 9 24/09/14 SRIHI SALEM 30,00 10 30/09/14 SANI MASSIMILIANO 30,00 11 22/12/15 HILAJ BENARD 30,00 12 07/11/14 JEMILI JAMEL 29,50 13 24/07/14 ANTONCIUC LARISA 29,00 14 07/08/14 LOUIGAT FATIMA 29,00 15 18/09/14 FAZLJII SALJI 29,00 16 18/08/15 KULYK EMILIYA 29,00 17 22/09/15 SINGH RANJIT 29,00 18 24/11/15 OBOROCEA VLADIMIR 29,00 19 18/09/14 CILIBERTI EMANUELE 28,50 20 26/09/14 GARDENGHI MARIA PAOLA 28,00 21 21/08/14 MASINA MAURIZIA 27,50 22 11/09/14 TEYOU JEAN CLAUDE 27,50 23 20/10/14 PRISACARU MARIA 27,50 24 18/11/14 PETRASCU ANNA 27,50 25 22/07/14 TROMBONI SILVANO 27,00 26 14/08/14 OKOIZIDE CHRISTIANA 27,00 27 11/09/14 KUSIAK IWONA 27,00 28 18/09/14 COLLADO LADY ALT DEL ROSARIO 27,00 29 30/09/14 ZBANCHUK OLEKSANDR 27,00 30 30/09/14 NICOLI BEATRICE 27,00 31 30/09/14 BARYLO EDUARD 27,00 32 01/10/14 ORI LORENZO 27,00 33 28/01/15 WILLIAMS AMINA 27,00 1 34 07/08/14 GHALA ABDELATI 26,50 35 06/08/14 KOTEI DAVID 26,50 36 20/08/14 KUL'CHYK LYUDMYLA 26,50 37 23/09/14 KONDAKCIU PASK 26,50 38 23/09/14 GRAVA CHIARA 26,50 39 24/09/14 GRITCO LUDMILA 26,50 40 24/09/14 NUGNES ANTONIO DANIEL 26,50 41 24/09/14 ENNAKHLI ABDELILAH 26,50 42 24/09/14 EL MOUNADIL ABDERRAZZAK -

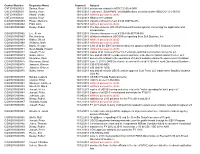

Control Number

Control Number Requester Name Scanned Subject CNT2013000029 Santos, Rose 10/31/2013 documents related to HSSCCG-05-A-0031 CNT2013000030 Santos, Rose 10/31/2013 Task order, SOW/PWS, and Modifications associated with HSSCCG-12-J-00120 CNT2013000031 Khalaf, Vivian 10/31/2013 withheld pursuant to (b)(6) CNT2013000032 Santos, Rose 11/14/2013 HSSCCG11C00020 COW2013000863 Power, Mentoria 10/25/2013 Vacancy Announcement # CIS-936772-ATL COW2013000864 Pratt, John 10/25/2013 withheld pursuant to (b)(6) COW2013000865 Deasy, Robert 10/31/2013 The December 6, 2012 DHS General Counsel opinion concerning the application and interpretation.. COW2013000866 Lee, Kevin 10/31/2013 Vacancy Announcement # CIS-PJN-957799-OIT COW2013000867 Rai, Hardeep 10/31/2013 all documentation in USCIS files regarding Beta Soft Systems, Inc. COW2013000868 Walter, Sheryl 10/31/2013 withheld pursuant to (b)(6) COW2013000869 Williams, Mark 10/31/2013 withheld pursuant to (b)(6) COW2013000870 Bruno, George 10/31/2013 a list of all the EB-5 investment projects sponsored by the EB-5 Regional Centers COW2013000871 Seon-Spada, Hyosim 10/31/2013 withheld pursuant to (b)(6) COW2013000872 Joseph, Peter 10/31/2013 copies of all notices of Intent to Terminate and final termination notices for all... COW2013000873 Gulko, Asher 10/31/2013 any and all USCIS records used to authorize Lake Buena Vista Regional Center, LLC COW2013000874 Sampson, Zack 10/31/2013 documents related to the operations of federal websites during the government shutdown COW2013000875 Gluckman, David 10/31/2013 June