SAUROMALUS {Dvmtkll 1856), the CHUCKWALLAS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chuckwalla Habitat in Nevada

Final Report 7 March 2003 Submitted to: Division of Wildlife, Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, State of Nevada STATUS OF DISTRIBUTION, POPULATIONS, AND HABITAT RELATIONSHIPS OF THE COMMON CHUCKWALLA, Sauromalus obesus, IN NEVADA Principal Investigator, Edmund D. Brodie, Jr., Department of Biology, Utah State University, Logan, UT 84322-5305 (435)797-2485 Co-Principal Investigator, Thomas C. Edwards, Jr., Utah Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit and Department of Fisheries and Wildlife, Utah State University, Logan, UT 84322-5210 (435)797-2509 Research Associate, Paul C. Ustach, Department of Biology, Utah State University, Logan, UT 84322-5305 (435)797-2450 1 INTRODUCTION As a primary consumer of vegetation in the desert, the common chuckwalla, Sauromalus obesus (=ater; Hollingsworth, 1998), is capable of attaining high population density and biomass (Fitch et al., 1982). The 21 November 1991 Federal Register (Vol. 56, No. 225, pages 58804-58835) listed the status of chuckwalla populations in Nevada as a Category 2 candidate for protection. Large size, open habitat and tendency to perch in conspicuous places have rendered chuckwallas particularly vulnerable to commercial and non-commercial collecting (Fitch et al., 1982). Past field and laboratory studies of the common chuckwalla have revealed an animal with a life history shaped by the fluctuating but predictable desert climate (Johnson, 1965; Nagy, 1973; Berry, 1974; Case, 1976; Prieto and Ryan, 1978; Smits, 1985a; Abts, 1987; Tracy, 1999; and Kwiatkowski and Sullivan, 2002a, b). Life history traits such as annual reproductive frequency, adult survivorships, and population density have all varied, particular to the population of chuckwallas studied. Past studies are mostly from populations well within the interior of chuckwalla range in the Sonoran Desert. -

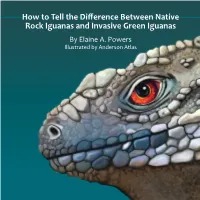

How to Tell the Difference Between Native Rock Iguanas and Invasive Green Iguanas by Elaine A

How to Tell the Difference Between Native Rock Iguanas and Invasive Green Iguanas By Elaine A. Powers Illustrated by Anderson Atlas Many of the islands in the Caribbean Sea, known as the West Rock Iguanas (Cyclura) Indies, have native iguanas. B Cuban Rock Iguana (Cyclura nubila), Cuba They are called Rock Iguanas. C Sister Isles Rock Iguana (Cyclura nubila caymanensis), Cayman Brac and Invasive Green Iguanas have been introduced on these islands and Little Cayman are a threat to the Rock Iguanas. They compete for food, territory D Grand Cayman Blue Iguana (Cyclura lewisi), Grand Cayman and nesting areas. E Jamaican Rock Iguana (Cyclura collei), Jamaica This booklet is designed to help you identify the native Rock F Turks & Caicos Rock Iguana (Cyclura carinata), Turks and Caicos. Iguanas from the invasive Greens. G Booby Cay Rock Iguana (Cyclura carinata bartschi), Booby Cay, Bahamas H Andros Rock Iguana (Cyclura cychlura), Andros, Bahamas West Indies I Exuma Rock Iguana (Cyclura cychlura figginsi), Exuma Islands, Bahamas Exumas BAHAMAS J Allen’s Cay Rock Iguana (Cyclura cychlura inornata), Exuma Islands, J Islands Bahamas M San Salvador Andros Island H Booby Cay K Anegada Iguana (Cyclura pinguis), British Virgin Islands Allens Cay White G I Cay Ricord’s Iguana (Cyclura ricordi), Hispaniola O F Turks & Caicos L CUBA NAcklins Island M San Salvador Rock Iguana (Cyclura rileyi), San Salvador, Bahamas Anegada HISPANIOLA CAYMAN ISLANDS K N Acklins Rock Iguana (Cyclura rileyi nuchalis), Acklins Islands, Bahamas B PUERTO RICO O White Cay Rock Iguana (Cyclura rileyi cristata), Exuma Islands, Bahamas Grand Cayman D C JAMAICA BRITISH P Rhinoceros Iguana (Cyclura cornuta), Hispanola Cayman Brac & VIRGIN Little Cayman E L P Q Mona ISLANDS Q Mona Island Iguana (Cyclura stegnegeri), Mona Island, Puerto Rico Island 2 3 When you see an iguana, ask: What kind do I see? Do you see a big face scale, as round as can be? What species is that iguana in front of me? It’s below the ear, that’s where it will be. -

The Reduction of Seri Indian Range and Residence in the State of Sonora, Mexico (1563-Present)

The reduction of Seri Indian range and residence in the state of Sonora, Mexico (1563-present) Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Bahre, Conrad J. Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 24/09/2021 15:06:07 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/551967 THE REDUCTION OF SERI INDIAN RANGE AND RESIDENCE IN THE STATE OF SONORA, MEXICO (1536-PRESENT) by Conrad Joseph Bahre A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF GEOGRAPHY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 1 9 6 7 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This thesis has been submitted in partial fulfill ment of requirements for an advanced degree at The University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that accurate acknowl edgment of source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department or the Dean of the Graduate College when in his judgment the proposed use of the material is in the inter ests of scholarship. In all other instances, however, permission must be obtained from the author. -

Volcanoes & Land Iguanas

Volcanoes & Land Iguanas 1/2 Background Galapagos iguanas are thought to of arrived in the Galapagos archipelago by floating on of rafts of vegetation from the South American continent. It is estimated that a split of iguana species into Land and Marine Iguanas occurred around 10.5 million years ago. In Galapagos, 3 species of land Iguanas now exist. The Land Iguanas include: Conolophus subcristatus (found on 6 islands), Conolophus pallidus (found only on Santa Fe Island) and a third species Conolophus rosada (known for its pink colour) is found on Wolf volcano on Isabela Island. Habitat Land Iguanas are found in the drier areas of the island. Being cold- blooded, to keep warm they bask in the sun and on the volcanic rock, escaping the midday sun by finding shade under vegetation and rocks, and sleeping in burrows to conserve their body heat. Land Iguanas feed on vegetation such as fallen fruits and cactus pads and even the spines of prickly pear © David cactus. Phillips © Galapagos Conservation © Cyder Trust Volcanoes & Land Iguanas 2/2 Reproduction Between 6 and 10 years of age, male Land Iguanas become highly aggressive, fighting for the attention of the female Land Iguanas. Mating then takes place at the end of the year and eggs are usually laid between January and March (June on Fernandina!). However, in order to lay these eggs female Land Iguanas have no option but to scale to the summit of volcanoes. © Phil Herbert The Volcanic Importance Every pregnant female will need to find a patch of volcanic ash; these pockets of warm soft soil are perfect for the incubation of their eggs; however these sites are difficult to come by. -

Sauromalus Hispidus

ARTÍCULOS CIENTÍFICOS Cerdá-Ardura & Langarica-Andonegui 2018 - Sauromalus hispidus in Rasa Island- p 17-28 ON THE PRESENCE OF THE SPINY CHUCKWALLA SAUROMALUS HISPIDUS (STEJNEGER, 1891) IN RASA ISLAND, MEXICO PRESENCIA DEL CHACHORÓN ESPINOSO SAUROMALUS HISPIDUS (STEJNEGER, 1891) EN LA ISLA DE RASA, MÉXICO Adrián Cerdá-Ardura1* and Esther Langarica-Andonegui2 1Lindblad Expeditions/National Geographic. 2Facultad de Ciencias, Uiversidad Nacional Autónoma de México, CDMX, México. *Correspondence author: [email protected] Abstract.— In 2006 and 2013 two different individuals of the Spiny Chuckwalla (Sauromalus hispidus) were found on the small, flat, volcanic and isolated Rasa Island, located in the Midriff Region of the Gulf of California, Mexico. This species had never been recorded from Rasa Island prior to 2006. A new field study in 2014 revealed the presence of a single female chuckwalla inhabiting the Tapete Verde Valley, in the south-central part of the island, occupying a territory no bigger than 10000 m2. A scat analysis shows that the only food consumed by the animal is the Alkali Weed (Cressa truxilliensis) that forms patches of carpets in its habitat. The individual is in precarious condition, as it seems to starve on a seasonal basis, especially during El Niño cycles; also, it is missing fingers and toes, which appear to be intentional markings by amputation. We conclude that the two individuals were introduced to the island intentionally by humans. Keywords.— Chuckwalla, Gulf of California, Rasa Island. Resumen.— En 2006 y 2013 se encontraron dos individuos diferentes del cachorón de roca o chuckwalla espinoso (Sauromalus hispidus) en la pequeña, plana, volcánica y aislada isla Rasa, localizada en la Región de las Grandes Islas, en el Golfo de California, México. -

A Distributional Survey of the Birds of Sonora, Mexico

52 A. J. van Rossem Occ. Papers Order FALCONIFORMES Birds of PreY Family Cathartidae American Vultures Coragyps atratus (Bechstein) Black Vulture Vultur atratus Bechstein, in Latham, Allgem. Ueb., Vögel, 1, 1793, Anh., 655 (Florida). Coragyps atratus atratus van Rossem, 1931c, 242 (Guaymas; Saric; Pesqueira: Obregon; Tesia); 1934d, 428 (Oposura). — Bent, 1937, 43, in text (Guaymas: Tonichi). — Abbott, 1941, 417 (Guaymas). — Huey, 1942, 363 (boundary at Quito vaquita) . Cathartista atrata Belding, 1883, 344 (Guaymas). — Salvin and Godman, 1901. 133 (Guaymas). Common, locally abundant, resident of Lower Sonoran and Tropical zones almost throughout the State, except that there are no records as yet from the deserts west of longitude 113°, nor from any of the islands. Concentration is most likely to occur in the vicinity of towns and ranches. A rather rapid extension of range to the northward seems to have taken place within a relatively few years for the species was not noted by earlier observers anywhere north of the limits of the Tropical zone (Guaymas and Oposura). It is now common nearly everywhere, a few modern records being Nogales and Rancho La Arizona southward to Agiabampo, with distribution almost continuous and with numbers rapidly increasing southerly, May and June, 1937 (van Rossem notes); Pilares, in the north east, June 23, 1935 (Univ. Mich.); Altar, in the northwest, February 2, 1932 (Phillips notes); Magdalena, May, 1925 (Dawson notes; [not noted in that locality by Evermann and Jenkins in July, 1887]). The highest altitudes where observed to date are Rancho La Arizona, 3200 feet; Nogales, 3850 feet; Rancho Santa Bárbara, 5000 feet, the last at the lower fringe of the Transition zone. -

Iguanid and Varanid CAMP 1992.Pdf

CONSERVATION ASSESSMENT AND MANAGEMENT PLAN FOR IGUANIDAE AND VARANIDAE WORKING DOCUMENT December 1994 Report from the workshop held 1-3 September 1992 Edited by Rick Hudson, Allison Alberts, Susie Ellis, Onnie Byers Compiled by the Workshop Participants A Collaborative Workshop AZA Lizard Taxon Advisory Group IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group SPECIES SURVIVAL COMMISSION A Publication of the IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group 12101 Johnny Cake Ridge Road, Apple Valley, MN 55124 USA A contribution of the IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group, and the AZA Lizard Taxon Advisory Group. Cover Photo: Provided by Steve Reichling Hudson, R. A. Alberts, S. Ellis, 0. Byers. 1994. Conservation Assessment and Management Plan for lguanidae and Varanidae. IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group: Apple Valley, MN. Additional copies of this publication can be ordered through the IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group, 12101 Johnny Cake Ridge Road, Apple Valley, MN 55124. Send checks for US $35.00 (for printing and shipping costs) payable to CBSG; checks must be drawn on a US Banlc Funds may be wired to First Bank NA ABA No. 091000022, for credit to CBSG Account No. 1100 1210 1736. The work of the Conservation Breeding Specialist Group is made possible by generous contributions from the following members of the CBSG Institutional Conservation Council Conservators ($10,000 and above) Australasian Species Management Program Gladys Porter Zoo Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum Sponsors ($50-$249) Chicago Zoological -

Roatán Spiny-Tailed Iguana (Ctenosaura Oedirhina) Conservation Action Plan 2020–2025 Edited by Stesha A

Roatán spiny-tailed iguana (Ctenosaura oedirhina) Conservation action plan 2020–2025 Edited by Stesha A. Pasachnik, Ashley B.C. Goode and Tandora D. Grant INTERNATIONAL UNION FOR CONSERVATION OF NATURE IUCN IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature, helps the world find pragmatic solutions to our most pressing environment and development challenges. IUCN works on biodiversity, climate change, energy, human livelihoods and greening the world economy by supporting scientific research, managing field projects all over the world, and bringing governments, NGOs, the UN and companies together to develop policy, laws and best practice. IUCN is the world’s oldest and largest global environmental organization, with more than 1,400 government and NGO members and almost 15,000 volunteer experts in some 160 countries. IUCN’s work is supported by around 950 staff in more than 50 countries and hundreds of partners in public, NGO and private sectors around the world. www.iucn.org IUCN Species Programme The IUCN Species Programme supports the activities of the IUCN Species Survival Commission and individual Specialist Groups, as well as implementing global species conservation initiatives. It is an integral part of the IUCN Secretariat and is managed from IUCN’s international headquarters in Gland, Switzerland. The Species Programme includes a number of technical units covering Wildlife Trade, the Red List, Freshwater Biodiversity Assessments (all located in Cambridge, UK), and the Global Biodiversity Assessment Initiative (located in Washington DC, USA). IUCN Species Survival Commission The Species Survival Commission (SSC) is the largest of IUCN’s six volunteer commissions with a global membership of more than 9,000 experts. -

Microhabitat Selection of the Poorly Known Lizard Tropidurus Lagunablanca (Squamata: Tropiduridae) in the Pantanal, Brazil

ARTICLE Microhabitat selection of the poorly known lizard Tropidurus lagunablanca (Squamata: Tropiduridae) in the Pantanal, Brazil Ronildo Alves Benício¹; Daniel Cunha Passos²; Abraham Mencía³ & Zaida Ortega⁴ ¹ Universidade Regional do Cariri (URCA), Centro de Ciências Biológicas e da Saúde (CCBS), Departamento de Ciências Biológicas (DCB), Laboratório de Herpetologia, Programa de Pós-Graduação em Diversidade Biológica e Recursos Naturais (PPGDR). Crato, CE, Brasil. ORCID: http://orcid.org/0000-0002-7928-2172. E-mail: [email protected] (corresponding author) ² Universidade Federal Rural do Semi-Árido (UFERSA), Centro de Ciências Biológicas e da Saúde (CCBS), Departamento de Biociências (DBIO), Laboratório de Ecologia e Comportamento Animal (LECA), Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ecologia e Conservação (PPGEC). Mossoró, RN, Brasil. ORCID: http://orcid.org/0000-0002-4378-4496. E-mail: [email protected] ³ Universidade Federal de Mato Grosso do Sul (UFMS), Instituto de Biociências (INBIO), Programa de Pós-Graduação em Biologia Animal (PPGBA). Campo Grande, MS, Brasil. ORCID: http://orcid.org/0000-0001-5579-2031. E-mail: [email protected] ⁴ Universidade Federal de Mato Grosso do Sul (UFMS), Instituto de Biociências (INBIO), Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ecologia e Conservação (PPGEC). Campo Grande, MS, Brasil. ORCID: http://orcid.org/0000-0002-8167-1652. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract. Understanding how different environmental factors influence species occurrence is a key issue to address the study of natural populations. However, there is a lack of knowledge on how local traits influence the microhabitat use of tropical arboreal lizards. Here, we investigated the microhabitat selection of the poorly known lizard Tropidurus lagunablanca (Squamata: Tropiduridae) and evaluated how environmental microhabitat features influence animal’s presence. -

Effects of Habitat on Clutch Size of Ornate Tree Lizards, Urosaurus Ornatus

Western North American Naturalist Volume 71 Number 2 Article 12 8-12-2011 Effects of habitat on clutch size of ornate tree lizards, Urosaurus ornatus Gregory Haenel Elon University, Elon, North Carolina, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/wnan Part of the Anatomy Commons, Botany Commons, Physiology Commons, and the Zoology Commons Recommended Citation Haenel, Gregory (2011) "Effects of habitat on clutch size of ornate tree lizards, Urosaurus ornatus," Western North American Naturalist: Vol. 71 : No. 2 , Article 12. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/wnan/vol71/iss2/12 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Western North American Naturalist Publications at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Western North American Naturalist by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Western North American Naturalist 71(2), © 2011, pp. 247–256 EFFECTS OF HABITAT ON CLUTCH SIZE OF ORNATE TREE LIZARDS, UROSAURUS ORNATUS Gregory Haenel1 ABSTRACT.—Clutch size is an important determinant of female reproductive success in reptiles. Although female body size explains much variation in clutch size, other important factors include differences in food availability, predation risk, morphology, and demography. Ornate tree lizards, Urosaurus ornatus, display extensive variation in life history traits, including clutch size. Tree lizards primarily use 2 distinct habitat types—trees and rock surfaces—which influence both the performance and morphology of this species and may affect life history traits such as clutch size. As food availability, micro- climate, and, potentially, predator escape probabilities differ between these 2 habitats, I predicted that tree- and rock- dwelling lizards would allocate resources toward clutch size differently. -

RHINOCEROS IGUANA Cyclura Cornuta Cornuta (Bonnaterre 1789)

HUSBANDRY GUIDELINES: RHINOCEROS IGUANA Cyclura cornuta cornuta (Bonnaterre 1789) REPTILIA: IGUANIDAE Compiler: Cameron Candy Date of Preparation: DECEMBER, 2009 Institute: Western Sydney Institute of TAFE, Richmond, NSW, Australia Course Name/Number: Certificate III in Captive Animals - 1068 Lecturers: Graeme Phipps - Jackie Salkeld - Brad Walker Husbandry Guidelines: C. c. cornuta 1 ©2009 Cameron Candy OHS WARNING RHINOCEROS IGUANA Cyclura c. cornuta RISK CLASSIFICATION: INNOCUOUS NOTE: Adult C. c. cornuta can be reclassified as a relatively HAZARDOUS species on an individual basis. This may include breeding or territorial animals. POTENTIAL PHYSICAL HAZARDS: Bites, scratches, tail-whips: Rhinoceros Iguanas will defend themselves when threatened using bites, scratches and whipping with the tail. Generally innocuous, however, bites from adults can be severe resulting in deep lacerations. RISK MANAGEMENT: To reduce the risk of injury from these lizards the following steps should be followed: - Keep animal away from face and eyes at all times - Use of correct PPE such as thick gloves and employing correct and safe handling techniques when close contact is required. Conditioning animals to handling is also generally beneficial. - Collection Management; If breeding is not desired institutions can house all female or all male groups to reduce aggression - If aggressive animals are maintained protective instrument such as a broom can be used to deflect an attack OTHER HAZARDS: Zoonosis: Rhinoceros Iguanas can potentially carry the bacteria Salmonella on the surface of the skin. It can be passed to humans through contact with infected faeces or from scratches. Infection is most likely to occur when cleaning the enclosure. RISK MANAGEMENT: To reduce the risk of infection from these lizards the following steps should be followed: - ALWAYS wash hands with an antiseptic solution and maintain the highest standards of hygiene - It is also advisable that Tetanus vaccination is up to date in the event of a severe bite or scratch Husbandry Guidelines: C. -

NAME: Land Iguana and Marine Iguana – Both in the Family Iguanidae CLASSIFICATION: Land: Ge- Nus Conolophus; Species (Two) Su

Grab & Go NAME: Land Iguana and Marine Iguana – both in the Family Iguanidae CLASSIFICATION: Land: Ge- nus Conolophus; Species (two) subcristatus and pallidus Marine: Genus Amblyrhynchus; Species cristatus MAIN MESSAGES: The Galapagos are a quintessential example of islands as living laboratories of evolution. ✤ Beginning with Darwin and Wallace, the study of islands has provided insight into how organisms colo- nize new environments and, through successive genera- tions, undergo changes that make their descendants more suited to thrive in the new environment CAS has made research ex- peditions to the Galapagos and has been involved in conservation efforts there for over 100 years. ✤ CAS collections from the Galapagos are the best in the world. Today, the Academy continues its research in the Galapagos and maintains the best collection of Galapagos materials in the world. Scientists at CAS collect plants and animals on research expedi- tions around the world. Their work and Academy collections provide invaluable baseline information about human impacts and change over time. DISTRIBUTION AND HABITAT: All are inhabitants of the Galapagos Islands. A spiny- tailed Central American Iguana may be ancestral to all three, but the marine species evolved from the terrestrial iguanas and thus is endemic to the Galapagos. Further, it is the only sea-going iguana in the world, and spends its entire life in the intertidal/sub- tidal zones. Although the land iguanas live on several islands, they are mostly seen on Plaza Sur. More widespread, the marine iguanas are seen in the channel between Isa- bella and Fernandina and along the cliffs of Espanola. DESCRIPTION AND DIET: Marine iguanas may range from 2 to 20 lbs, usually with a blackish color.