Ÿþl G 9 2 C O V E R . J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contents More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-58131-8 - Greater Medieval Houses of England and Wales 1300–1500: Volume II: East Anglia, Central England, and Wales Anthony Emery Table of Contents More information CONTENTS Acknowledgements page xii List of abbreviations xiv Introduction 1 PART I EAST ANGLIA 1 East Anglia: historical background 9 Norfolk 9 / Suffolk 12 / Essex 14 / The Peasants’ Revolt of 1381 15 / Cambridgeshire 16 / Late medieval art in East Anglia 16 2 East Anglia: architectural introduction 19 Castles 19 / Fortified houses 20 / Stone houses 21 / Timber- framed houses 22 / Brick houses 25 / Monastic foundations 29 / Collegiate foundations 30 / Moated sites 31 3 Monastic residential survivals 35 4 East Anglia: bibliography 45 5 East Anglia: survey 48 Abington Pigotts, Downhall Manor 48 / Baconsthorpe Castle 49 / Burwell Lodging Range 50 / Bury St Edmunds, Abbot’s House 51 / Butley Priory and Suffolk monastic gatehouses 53 / Caister Castle 56 / Cambridge, Corpus Christi College and the early development of the University 61 / Cambridge, The King’s Hall 65 / Cambridge, Queens’ College and other fifteenth century University foundations 68 / Carrow Priory 73 / Castle Acre, Prior’s Lodging 74 / Chesterton Tower 77 / Clare, Prior’s Lodging 78 / Claxton Castle 79 / Denny Abbey 80 / Downham Palace 83 / East Raynham Old Hall and other displaced Norfolk houses 84 / Elsing Hall 86 / Ely, Bishop’s Palace 89 / Ely, Prior’s House and Guest Halls 90 / Ely, Priory Gate 96 / Faulkbourne Hall 96 / Framsden Hall 100 / Giffords Hall 102 / Gifford’s Hall -

Corner House, 8, Acton Burnell, Shrewsbury, SY5 7PE 01743

FOR SALE Offers in the region of £385,000 Corner House, 8, Acton Burnell, Shrewsbury, SY5 7PE Property to sell? We would be who is authorised and regulated delighted to provide you with a free by the FSA. Details can be no obligation market assessment provided upon request. Do you of your existing property. Please require a surveyor? We are contact your local Halls office to able to recommend a completely make an appointment. Mortgage/ independent chartered surveyor. A beautiful and spacious listed Grade II detached period house with pretty financial advice. We are able Details can be provided upon gardens and garaging in a sought after conservation village. to recommend a completely request. independent financial advisor, hallsgb.com 01743 236444 FOR SALE Mileages: Shrewsbury - 8.9 Miles, Church Stretton - 9 Miles, Much Wenlock - 9.5 miles, Telford - 19.2 miles (All distances are approximate) boarded floor is provided to the dining room and quarry tiled floors to both ■ Desirable village location the breakfast kitchen and utility room. ■ Spacious accommodation Outside there is ample driveway, a useful double garage and a separate ■ 3 Receptions/4 Beds/2 Bath brick garden store. The gardens extend around the property and incorporate a number of charming features. ■ Wealth of character & charm ■ Attractive gardens ACCOMMODATION ■ Double garage RECEPTION HALL With cornice ceiling, painted part wall panelling, staircase to first floor DIRECTIONS From Shrewsbury take the A458 Brignorth Road over the A5 by-pass then GUEST CLOAKS/WC take the first turn right sign posted Acton Burnell. Continue along this road With wash hand basin and low flush WC. -

Heritage at Risk Register 2013

HERITAGE AT RISK 2013 / WEST MIDLANDS Contents HERITAGE AT RISK III Worcestershire 64 Bromsgrove 64 Malvern Hills 66 THE REGISTER VII Worcester 67 Content and criteria VII Wychavon 68 Criteria for inclusion on the Register VIII Wyre Forest 71 Reducing the risks X Publications and guidance XIII Key to the entries XV Entries on the Register by local planning authority XVII Herefordshire, County of (UA) 1 Shropshire (UA) 13 Staffordshire 27 Cannock Chase 27 East Staffordshire 27 Lichfield 29 NewcastleunderLyme 30 Peak District (NP) 31 South Staffordshire 32 Stafford 33 Staffordshire Moorlands 35 Tamworth 36 StokeonTrent, City of (UA) 37 Telford and Wrekin (UA) 40 Warwickshire 41 North Warwickshire 41 Nuneaton and Bedworth 43 Rugby 44 StratfordonAvon 46 Warwick 50 West Midlands 52 Birmingham 52 Coventry 57 Dudley 59 Sandwell 61 Walsall 62 Wolverhampton, City of 64 II Heritage at Risk is our campaign to save listed buildings and important historic sites, places and landmarks from neglect or decay. At its heart is the Heritage at Risk Register, an online database containing details of each site known to be at risk. It is analysed and updated annually and this leaflet summarises the results. Heritage at Risk teams are now in each of our nine local offices, delivering national expertise locally. The good news is that we are on target to save 25% (1,137) of the sites that were on the Register in 2010 by 2015. From St Barnabus Church in Birmingham to the Guillotine Lock on the Stratford Canal, this success is down to good partnerships with owners, developers, the Heritage Lottery Fund (HLF), Natural England, councils and local groups. -

The Environmental Economy of the West Midlands

FINAL REPORT Advantage West Midlands, the Environment Agency and Regional Partners in the West Midlands The Environmental Economy of the West Midlands January 2001 Reference 6738 This report has been prepared by Environmental Resources Management the trading name of Environmental Resources Management Limited, with all reasonable skill, care and diligence within the terms of the Contract with the client, incorporating our General Terms and Conditions of Business and taking account of the resources devoted to it by agreement with the client. We disclaim any responsibility to the client and others in respect of any matters outside the scope of the above. This report is confidential to the client and we accept no responsibility of whatsoever nature to third parties to whom this report, or any part thereof, is made known. Any such party relies on the report at their own risk. In line with our company environmental policy we purchase paper for our documents only from ISO 14001 certified or EMAS verified manufacturers. This includes paper with the Nordic Environmental Label. CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY i 1. INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 LINKAGES BETWEEN ENVIRONMENT AND THE ECONOMY 1 1.2 STUDY AIMS 1 1.3 THE REGIONAL CONTEXT 1 1.4 STRUCTURE OF THIS REPORT 3 2. STUDY SCOPE 4 2.1 ENVIRONMENTAL INDUSTRY 4 2.2 LAND BASED INDUSTRY 4 2.3 CAPITALISING ON A HIGH QUALITY ENVIRONMENT 4 3. ENVIRONMENTAL INDUSTRY 5 3.1 OVERVIEW 5 3.2 BUSINESSES SUPPLYING ENVIRONMENTAL GOODS & SERVICES 5 3.3 ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT IN INDUSTRY 13 3.4 ENVIRONMENTAL POSTS IN THE PUBLIC SECTOR 14 3.5 ENVIRONMENTAL ACADEMIC INSTITUTIONS 14 3.6 NON-PROFIT MAKING ENVIRONMENTAL ORGANISATIONS 15 3.7 ENVIRONMENTAL CONSERVATION & ENHANCEMENT SECTOR 16 3.8 SUMMARY 18 4. -

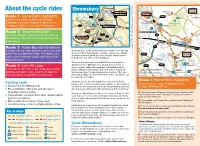

About the Cycle Rides

Sundorne Harlescott Route 45 Rodington About the cycle rides Shrewsbury Sundorne Mercian Way Heath Haughmond to Whitchurch START Route 1 Abbey START Route 2 START Route 1 Home Farm Highlights B5067 A49 B5067 Castlefields Somerwood Rodington Route 81 Gentle route following Route 81 through Monkmoor Uffington and Upton Magna to Home Farm, A518 Pimley Manor Haughmond B4386 Hill River Attingham. Option to extend to Rodington. Town Centre START Route 3 Uffington Roden Kingsland Withington Route 2 Around Attingham Route 44 SHREWSBURY This ride combines some places of interest in Route 32 A49 START Route 4 Sutton A458 Route 81 Shrewsbury with visits to Attingham Park and B4380 Meole Brace to Wellington A49 Home Farm. A5 Upton Magna A5 River Tern Walcot Route 3 Acton Burnell Adventure © Crown copyright and database rights 2012 Ordnance Survey 100049049 A5 A longer ride for more experienced cyclists with Shrewsbury is a very attractive historic market town nestled in a loop of the River Severn. The town centre has a largely Berwick Route 45 great views of Wenlock Edge, The Wrekin and A5064 Mercian Way You are not permitted to copy, sub-licence, distribute or sell any of this data third parties in form unaltered medieval street plan and features several timber River Severn Wharf to Coalport B4394 visits to Acton Burnell Castle and Venus Pool framed 15th and 16th century buildings. Emstrey Nature Reserve Home Farm The town was founded around 800AD and has played a B4380 significant role in British history, having been the site of A458 Attingham Park Uckington Route 4 Lyth Hill Loop many conflicts, particularly between the English and the A rewarding ride, with a few challenging climbs Welsh. -

Village Directory2019

Village Directory 2019 ACTON BURNELL, PITCHFORD, FRODESLEY, RUCKLEY AND LANGLEY Ewes and lambs near Acton Burnell The Bus Stop at Frodesley CONTENTS Welcome 3 Shops and Post Offices 15 Defibrillators 4 Pubs, Cafes and Restaurants 15 The Parish Council 5 Local Chemists 16 Meet your Councillors 6 Veterinary Practices 16 Policing and Safety 8 Pitchford Village Hall 17 Health and Medical Services 8 Local Churches 18 Local Medical Practices 9 Local Clubs and Societies 19 Local Hospitals 10 Concord College Parish Rubbish Collection and Recycling 11 Swimming Club 20 Parish Map 12 Schools and Colleges 21 Bus Routes and Times 13 Acton Burnell WI 22 Libraries 14 Information provided in this directory is intended to provide a guide to local organisations and services available to residents in the parish of Acton Burnell. The information contained is not exhaustive, and the listing of any group, club, organisation, business or establishment should not be taken as an endorsement or recommendation. While every effort has been made to ensure that the information included is accurate, users of this directory should not rely on the information provided and must make their own enquiries, inspections and assessments as to suitability and quality of services. Village Directory 2019 WELCOME Welcome to the second edition of the Parish Directory for the communities of Acton Burnell, Pitchford, Frodesley, Ruckley and Langley. We have tried to include as much useful information as possible, but if there is something you think is missing, or something you would like to see included in the future, please let us know. We would like to thank the Parish Council for continuing to fund both Village Views and the Directory. -

Draft Minutes to Show That the Budget Had Been Discussed at the Meeting and Noted That the PC Has Currently Exceeded Its 2020/21 Budget by 8%

Page 1 of 4 Acton Burnell, Frodesley, Pitchford, Ruckley & Langley Parish Council Parish Council Meeting Tuesday 9 March 2021 at 7.30pm (This meeting took place via remote video link). MINUTES – DRAFT 21.3.1 The Chairman welcomed all to the meeting and explained the proceedings. 21.3.2 Present: Cllr J Long - Chair, Cllr P Harrison - Vice Chair, Cllr G Ball, Cllr C Cullis, Cllr T Johnson, Cllr A Argyropulo, Cllr G Davies, Cllr R Morgan, Cllr K Faulkner, County Cllr D Morris, A Morris – Clerk. Public Attendees: R Adams - Airband 21.3.3 Declarations of Interest: Cllr Morgan declared an interest in pending planning applications at Home Farm Barns and Hunter’s Moon. No decisions were made on these applications at this meeting. 21.3.4 Public Session: Standing orders suspended. The Chairman brought forward discussion of Local Broadband (BT & Airband) Agenda item 21.3.14. R Adams presented the Council with details of fibre cables being installed in Acton Burnell, Ruckley and Langley by Airband as part of Shropshire Council’s Connecting Shropshire project which aims to improve broadband speeds across Shropshire. He apologised for the lack of prior notice given to the Parish Council ahead of the works and said they should be complete within 8 weeks. Action: R Adams to liaise with Cllr Ball re any issues relating to works in Ruckley. Action: R Adams to provide the Clerk with a map of the route, Clerk to circulate to Councillors. Standing orders re-instated. 21.3.5 Minutes of previous meeting: Cllr Ball proposed an amendment to the draft minutes to show that the budget had been discussed at the meeting and noted that the PC has currently exceeded its 2020/21 budget by 8%. -

The Shropshire (Structural Change) Order 2008 No

Draft Legislation: This is a draft item of legislation. This draft has since been made as a UK Statutory Instrument: The Shropshire (Structural Change) Order 2008 No. 492 This Draft Statutory Instrument has been printed in substitution for the Draft Statutory Instrument of the same title, which was laid on 17th December 2007, and is being issued free of charge to all known recipients of that Draft Statutory Instrument. Draft Order laid before Parliament under section 240(6) of the Local Government and Public Involvement in Health Act 2007, for approval by resolution of each House of Parliament. DRAFT STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS 2008 No. XXXX LOCAL GOVERNMENT, ENGLAND The Shropshire (Structural Change) Order 2008 Made - - - - 2008 Coming into force in accordance with article 1 This Order implements, without modification, a proposal, submitted to the Secretary of State for Communities and Local Government under section 2 of the Local Government and Public Involvement in Health Act 2007(1), that there should be a single tier of local government for the county of Shropshire. That proposal was made by Shropshire County Council. The Secretary of State did not make a request under section 4 of the Local Government and Public Involvement in Health Act 2007 (request for Boundary Committee for England’s advice). Before making the Order the Secretary of State consulted the following about the proposal— (a) every authority affected by the proposal(2) (except the authority which made it); and (b) other persons the Secretary of State considered appropriate. The Secretary of State for Communities and Local Government makes this Order in the exercise of the powers conferred by sections 7, 11, 12 and 13 of the Local Government and Public Involvement in Health Act 2007: (1) 2007 c.28. -

From Shropshire to the Weald

From Shropshire to the Weald Kettles and their kin in Kent and Sussex Pam Griffiths March 2015 Updated November 2015 Contents Page Trees 2 Acknowledgments, Disclaimers and Abbreviations 3 Introduction 4 Daniel Kettle – Lewisham, Croydon, London and Stockton-on-Tees 4 Kettle, Harris and Barber – Shropshire roots 8 John2 Kettle: Shropshire, Southwark and Lewes 21 Humphris or Humphrison: High Ercall, Uffington and Haughmond 31 John3 Kettle: Shropshire, Kent and Surrey 45 The earliest Richardsons – Yalding, Brenchley and Horsmonden 57 Daniel and Reeve: Horsmonden and Brenchley 62 Thomas2 Richardson: Brenchley, Horsmonden, Goudhurst, Withyham 63 The later Richardsons – Horsmonden and Withyham 71 Pearson, Pierson or Peirson – Horsmonden and Brenchley 79 Perrin, Peryn or Perryn – Horsmonden and Brenchley 91 Perrin distaff lines: Saxbie, Austen, Hope; Brenchley and Horsmonden 104 Dodge – mainly Goudhurst; some Ticehurst 127 Ballard – Cranbrook 138 Barham – Mainly Hawkhurst, Ticehurst and Wadhurst 144 The Lorkyn myth 165 The earliest Barhams – Wadhurst: doubtful territory 166 Barham distaff lines - Gibbon and Orglasse: mainly Hawkhurst 172 Trees Page Tree 1 – Descendants of Daniel Kettle 7 Tree 2 – Descendants of John Kettle and Elizabeth Harrington 10 Tree 3 – Descendants of Thomas and Mary Harrington 12 Tree 4 – Descendants of Thomas Kettle and Mary Harris 16 Tree 5 – Descendants of John Kettle and Mary Humphrison 24 Tree 6 - Kettle/Evans connections 31 Tree 7 – Descendants of Robert Humphrison 36 Tree 8 – Family of John Kettle and Sarah Richardson -

Acton Burnell, Frodesley, Pitchford, Ruckley & Langley Parish Council

Page 1 of 2 Acton Burnell, Frodesley, Pitchford, Ruckley & Langley Parish Council Parish Council Meeting Tuesday 8th Sep 2020 at 7.30pm This Meeting will take place via remote video link. You can join the meeting by clicking on the meeting link which will be sent to you on request. Members of the public and the press are welcome to attend. Please contact the Clerk or your local Councillor prior to the meeting. If you wish to speak at the meeting please make this clear so that adequate provision can be made. Clerk: Elizabeth Wicks Tel: 07768 437032 Email: [email protected] AGENDA 20.9.1 Chairman’s Welcome 20.9.2 Present & Apologies 20.9.3 Declarations of Interest 20.9.4 Public Session 20.9.5 Confirmation and Acceptance of the Minutes of the Previous Meeting 20.9.6 Police Report 20.9.7 Shropshire Councillor’s Report 20.9.8 Defibrillators 20.9.9 Community Led Plan: Clerk to update on Action Items (See Clerk’s Report). 20.9.9.1 AB Village footpath extension 20.9.9.2 Traffic Calming 20.9.10 Highways Matters: 20.9.10.1 Clerk to report on highway matters (See Clerk’s report). 20.9.10.2 Councillors to report any additional highway matters. 20.9.11 Finance: 20.9.11.1 Council to approve payment of accounts (See list of Payments). 20.9.11.2 Council to consider and approve the Bank Reconciliation as presented by the Clerk. 20.9.11.3 Council to approve Clerk’s additional hours worked. -

Shropshire Councillor Report 11Th May 2020 from County Councillor, Dan Morris

Acton Burnell, Frodesley, Pitchford, Ruckley & Langley Parish Council The Granary, Lower Farm Court, Pitchford, Shrewsbury, Shropshire. SY5 7DW. Shropshire Councillor Report 11th May 2020 From County Councillor, Dan Morris. - SC full council meeting last week held virtually, only one item on the agenda which was to remove the statutory obligations for Shropshire councillors to physically attend official SC meetings until CV has relented. This will be examined again later in the year. - The next full council meeting scheduled at the moment is July 16th - SC cabinet met 28th April in a virtual setting, the next meetings are 15th June and then 6th July. - There is a small grants scheme available, please see link https://shropshire.gov.uk/coronavirus/resources-and-grant-funding-opportunities-for-local- communities/covid-19-small-grants-programme/. You will note that specifically mentioned are that the grant is available to Village Halls who have suffered loss of income as a result of the CV outbreak. The second tranche of funding of a pot of £25k shuts down with all applications in by May 22nd. There is a then further 3rd and final pot of £25k that will be opened up in June - The 5 SC waste and recycling centres are now open for essential use only. The word essential here is used I think to discourage lots of people coming at once and overwhelming the centres - Government has provided SC with around £18m of funding to help SC deal with the extra costs and loss of income suffered by the council as a result of CV. -

An Archaeological Analysis of Anglo-Saxon Shropshire A.D. 600 – 1066: with a Catalogue of Artefacts

An Archaeological Analysis of Anglo-Saxon Shropshire A.D. 600 – 1066: With a catalogue of artefacts By Esme Nadine Hookway A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of MRes Classics, Ancient History and Archaeology College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham March 2015 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract The Anglo-Saxon period spanned over 600 years, beginning in the fifth century with migrations into the Roman province of Britannia by peoples’ from the Continent, witnessing the arrival of Scandinavian raiders and settlers from the ninth century and ending with the Norman Conquest of a unified England in 1066. This was a period of immense cultural, political, economic and religious change. The archaeological evidence for this period is however sparse in comparison with the preceding Roman period and the following medieval period. This is particularly apparent in regions of western England, and our understanding of Shropshire, a county with a notable lack of Anglo-Saxon archaeological or historical evidence, remains obscure. This research aims to enhance our understanding of the Anglo-Saxon period in Shropshire by combining multiple sources of evidence, including the growing body of artefacts recorded by the Portable Antiquity Scheme, to produce an over-view of Shropshire during the Anglo-Saxon period.