1 MB 15Th May 2017 News-Watch Today Programme Article 50 Survey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Performing Politics Emma Crewe, SOAS, University of London

Westminster MPs: performing politics Emma Crewe, SOAS, University of London Intentions My aim is to explore the work of Westminster Members of Parliament (MPs) in parliament and constituencies and convey both the diversity and dynamism of their political performances.1 Rather than contrasting MPs with an idealised version of what they might be, I interpret MPs’ work as I see it. If I have any moral and political intent, it is to argue that disenchantment with politics is misdirected – we should target our critiques at politicians in government rather than in their parliamentary role – and to call for fuller citizens’ engagement with political processes. Some explanation of my fieldwork in the UK’s House of Commons will help readers understand how and why I arrived at this interpretation. In 2011 then Clerk of the House, Sir Malcolm Jack, who I knew from doing research in the House of Lords (1998-2002), ascertained that the Speaker was ‘content for the research to proceed’, and his successor, Sir Robert Rogers, issued me with a pass and assigned a sponsor. I roamed all over the Palace, outbuildings and constituencies during 2012 (and to a lesser extent in 2013) listening, watching and conversing wherever I went. This entailed (a) observing interaction in debating chambers, committee rooms and in offices (including the Table Office) in Westminster and constituencies, (b) over 100 pre-arranged unstructured interviews with MPs, former MPs, officials, journalists, MPs’ staff and peers, (c) following four threads: media/twitter exchanges, the Eastleigh by-election with the three main parties, scrutiny of the family justice part of the Children and Families Bill, and constituency surgeries, (d) advising parliamentary officials on seeking MPs’ feedback on House services. -

Downloaded from the ATTACHED

Downloaded from www.bbc.co.uk/radio4 THE ATTACHED TRANSCRIPT WAS TYPED FROM A RECORDING AND NOT COPIED FROM AN ORIGINAL SCRIPT. BECAUSE OF THE RISK OF MISHEARING AND THE DIFFICULTY IN SOME CASES OF IDENTIFYING INDIVIDUAL SPEAKERS, THE BBC CANNOT VOUCH FOR ITS COMPLETE ACCURACY. IN TOUCH – Sex Education TX: 27.02.2018 2040-2100 PRESENTER: PETER WHITE PRODUCER: GEORGINA HEWES White Good evening. Tonight, how to solve the challenges of teaching sex education to visually impaired students. And one day at work in an environment definitely not geared to blind and partially sighted people. Clip Walker I can’t imagine being able to find my way round here ever. De Cordova Well that’s why I’ve got my sighted assistant because they take away that stress. White We’ll be following in the footsteps of Marsha de Cordova as she gets to grips with the Aladdin’s cave that is Parliament. But first, I come from the era where sex education was little more than one lesson on human reproduction, with much confusing talk about things like gonads and gametes which bore very little relevance to what we really wanted to know about. For a totally blind child, like me, it was all a deep mystery and you’d like to think that we’ve moved on a bit since then. But as the Department for Education closes a consultation exercise on the subject it looks as if there could still be a long way to go. Jordan is in his last year at a mainstream academy in southeast London and he feels he got little from the sex education classes he attended. -

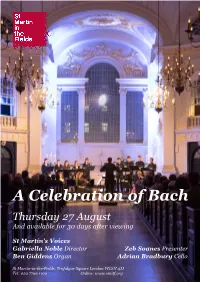

A Celebration of Bach Thursday 27 August and Available for 30 Days After Viewing

A Celebration of Bach Thursday 27 August And available for 30 days after viewing St Martin's Voices Gabriella Noble Director Zeb Soanes Presenter Ben Giddens Organ Adrian Bradbury Cello St Martin-in-the-Fields, Trafalgar Square London WC2N 4JJ Tel: 020 7766 1100 Online: www.smitf.org St Martin's Summer Online Festival 2020 St Martin’s is delighted to present St Martin’s Summer Online Festival. Our first concert series since March explores the musical heritage of St Martin’s and features a fresh look at our most-beloved repertoire. Although audiences will need to watch from home for now, all the concerts are recorded in St Martin’s and introduced by much loved BBC Radio 4 presenter and author Zeb Soanes. The performances are broadcast on Thursday evenings at 7.30pm, and available to watch for 30 days afterwards. Tonight's programme includes of some of Bach’s most beautiful and virtuosic choral motets on themes of religious longing, comfort and praise, intertwined with the haunting for Cello Suite No 4 and the celebrated Suite for Cello No 1. Please do keep an eye our final concert in our Summer Online Festival – The Glories of Venice (Thursday 3 September) – tickets are available through the St Martin’s website. As the impact of COVID-19 takes hold, we need people like you to keep helping us and the musicians we work with. Each concert in our festival costs around £2,000 to produce. If you are able to make a donation, please visit www.smitf.org/give. Thank you for helping to keep our doors open this year. -

'Pinkoes Traitors'

‘PINKOES AND TRAITORS’ The BBC and the nation, 1974–1987 JEAN SEATON PROFILE BOOKS First published in Great Britain in !#$% by Pro&le Books Ltd ' Holford Yard Bevin Way London ()$* +,- www.pro lebooks.com Copyright © Jean Seaton !#$% The right of Jean Seaton to be identi&ed as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright Designs and Patents Act $++/. All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN +4/ $ /566/ 545 6 eISBN +4/ $ /546% +$6 ' All reasonable e7orts have been made to obtain copyright permissions where required. Any omissions and errors of attribution are unintentional and will, if noti&ed in writing to the publisher, be corrected in future printings. Text design by [email protected] Typeset in Dante by MacGuru Ltd [email protected] Printed and bound in Britain by Clays, Bungay, Su7olk The paper this book is printed on is certi&ed by the © $++6 Forest Stewardship Council A.C. (FSC). It is ancient-forest friendly. The printer holds FSC chain of custody SGS-COC-!#6$ CONTENTS List of illustrations ix Timeline xvi Introduction $ " Mrs Thatcher and the BBC: the Conservative Athene $5 -

Score and Ignore: a Radio Listener's Guide to Ignoring Health Stories

Score and ignore A radio listener’s guide to ignoring health stories Do you shout at the morning radio when a story about a medical “risk” is distorted, exaggerated, mangled out of all recognition? Does your annoyance ruin your breakfast? You are not alone. Kevin McConway and David Spiegel- halter have developed a defence strategy to save their start-of-the-day sanity. Strike back at the presenters! And make it personal… When we wake up we are among the millions all of reporting, and applicability. In each case, a weaned] are more likely to eat fruit over the UK who turn on the Today programme on “yes” answer to the question indicates some and vegetables when they are older BBC Radio 4, presented by our favourite, veteran cause for concern about the report or the study than those given meals from jars and and generally excellent reporter John Humphrys. it is reporting on. A score of 12 “no” answers packets, researchers say.” This could be All over the US millions more tune in to simi- implies a perfect study, perfectly reported; 12 because the home-cooked food causes lar early news programmes with their own pet “yes” answers calls for apoplexy and vituperative the later eating behaviour, or it could be presenters. On many mornings there is a report letters to editors. Here goes: because some other aspect of the babies’ on the latest health risk story. At work we flip upbringing (a confounder) is associated through popular newspapers and there are more Study quality with both the weaning food and the later stories reporting the latest “research”, for exam- • Just observing people? diet. -

Television: Rules of Coverage

House of Commons Administration Committee Television: Rules of Coverage Second Report of Session 2012–13 Report, together with formal minutes and evidence Ordered by the House of Commons to be published 21 May 2012 HC 14 (incorporating HC 1818–i of Session 2010–12) Published on 13 June 2012 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited £0.00 The Administration Committee The Administration Committee is appointed to consider the services provided by and for the House of Commons. It also looks at services provided to the public by Parliament, including visitor facilities, the Parliament website and education services. Current membership Rt Hon. Sir Alan Haselhurst MP (Conservative, Saffron Walden) (Chair) Rosie Cooper MP (Labour, West Lancashire) Thomas Docherty MP (Labour, Dunfermline and West Fife) Graham Evans MP (Conservative, Weaver Vale) Rt Hon. Mark Francois MP (Conservative, Rayleigh and Wickford) Mark Hunter MP (Liberal Democrat, Cheadle) Mr Kevan Jones MP (Labour, North Durham) Simon Kirby MP (Conservative, Brighton Kemptown) Dr Phillip Lee MP (Conservative, Bracknell) Nigel Mills MP (Conservative, Amber Valley) Tessa Munt MP (Liberal Democrat, Wells) Sarah Newton MP (Conservative, Truro and Falmouth) Rt Hon. John Spellar MP (Labour, Warley) Mark Tami MP (Labour, Alyn and Deeside) Mr Dave Watts MP (Labour, St Helens North) Mike Weatherley MP (Conservative, Hove) The following members were also members of the committee during the inquiry: Geoffrey Clifton-Brown MP (Conservative, The Cotswolds) Bob Russell MP (Liberal Democrat, Colchester) Angela Smith MP (Labour, Penistone and Stocksbridge) Mr Shailesh Vara MP (Conservative, North West Cambridgeshire) Powers The powers of the Committee are set out in House of Commons Standing Order No 139, which is available on the Internet via www.parliament.uk. -

A Global Maritime Power

A Global Maritime Power Building a Better Future For Post-Brexit Britain Nusrat Ghani MP, Benjamin Barnard, Dominic Walsh, William Nicolle A Global Maritime Power Building a Better Future For Post-Brexit Britain Nusrat Ghani MP, Benjamin Barnard, Dominic Walsh, William Nicolle Policy Exchange is the UK’s leading think tank. We are an independent, non-partisan educational charity whose mission is to develop and promote new policy ideas that will deliver better public services, a stronger society and a more dynamic economy. Policy Exchange is committed to an evidence-based approach to policy development and retains copyright and full editorial control over all its written research. We work in partnership with academics and other experts and commission major studies involving thorough empirical research of alternative policy outcomes. We believe that the policy experience of other countries offers important lessons for government in the UK. We also believe that government has much to learn from business and the voluntary sector. Registered charity no: 1096300. Trustees Diana Berry, Alexander Downer, Pamela Dow, Andrew Feldman, David Harding, Patricia Hodgson, Greta Jones, Edward Lee, Charlotte Metcalf, David Ord, Roger Orf, Andrew Roberts, George Robinson, Robert Rosenkranz, William Salomon, Peter Wall, Simon Wolfson, Nigel Wright. A Global Maritime Power About the Author Nusrat Ghani MP is the Conservative MP for Wealden and a Senior Fellow at Policy Exchange. She previously served in the Department of Transport as Minister for Maritime between January 2018 and February 2020, during which time she became the first female Muslim Minister to speak from the House of Commons despatch box. -

A Gender Balance Guide for Media

Amplifying women’s voices A Gender Balance Guide For Media Insights Acknowledgements This guide is a Women In News publication April 2020 CONTRIBUTORS Rebecca Zausmer for Women in News (WAN-IFRA) Simone Flueckiger for Women in News (WAN-IFRA) WITH SPECIAL THANKS TO Kesewa Hennessy the Financial Times (UK) Marie-Louise Jarlenfors VK Media (Sweden) Laura Warne & Andrea Leung The South China Morning Post (Hong Kong) Mary Mbewe The Daily Nation (Zambia) Lara Bonilla & Marta Rodríguez ARA, (Spain) Pål Nedregotten Amedia (Norway) Laura Zelenko Bloomberg DESIGN BY Julie Chahine The development of this guide was made possible with the generous support of Sida This work is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike Women in News (WIN), an initiative by WAN-IFRA, WAN-IFRA is the global organisation of the world’s aims to increase women’s leadership and voices newspapers and news publishers, representing in the news. It does so by equipping women more than 18,000 publications, 15,000 online journalists and editors with the skills, strategies sites and over 3,000 companies in more than 120 and support networks they need to take on greater countries. WAN-IFRA is unique in its position as leadership positions and editorial influence within a global industry association with a human rights the industry. mandate to defend and promote media freedom, and the economic independence of news media as In parallel, WIN partners with media organisations an essential condition of that freedom. to identify industry-led solutions to close the gap between men and women in their newsrooms, WAN-IFRA applies a dual approach to supporting boardrooms and in the content they produce. -

Master Bibliography

SELECTED ITEMS OF MEDIA COVERAGE Selected Broadcast Comment Witness on BBC Radio 4 the Moral Maze, broadcast live at 2000 Wednesday 16th June 2010 Debate chaired by Quentin Cooper with Sir David King, Chris Whitty and Richard Davis, Material World, Radio 4 1630 Thursday 3rd January 2008 [on directions for science and innovation] Debate chaired by Sarah Montague with Tom Shakespeare, Today Programme, Radio 4 0850-0900, Friday Tuesday 4th September 2007 [on role of public in consultation on new technologies] D. Coyle, et al, Risky Business, Radio 4 ‘Analysis’ documentary, broadcast 11 December 2030, 14 December 2130, 2003 [interview on the precautionary principle] Tom Feilden, Political Interests in Biotechnology Science, Today Programme, Radio 4 0834-0843, Friday 19th September 2003 [on exercise of pressure in relation to GM Science Review Panel]. Roger Harrabin, Science Scares, Interview on the Today Programme, BBC Radio 4 0832, 10th January 2002 [on EEA report on risk and precaution]. ‘Sci-Files’, Australian National Radio, October 2000 [interview on risk, uncertainty and GM]. ‘Risk and Society’, The Commission, BBC Radio 4, 2000, 11 October 2000 [commission witness on on theme of risk and society] Selected Press Coverage of Work Andrew Jack, Battle Lines, Financial Times Magazine, 24th June 2011 [on need for tolerance of scepticism about science] Paul Dorfman, Who to Trust on Nuclear, Guardian, 14th April 2011 Charles Clover, Britain’s nuclear confidence goes into meltdown, Sunday Times, 20th March 2011 [on potential for a global sustainable -

22 May 2015 Page 1 of 17 SATURDAY 16 MAY 2015 SAT 06:57 Weather (B05tbnhj) Assistant Producer: Hannah Newton the Latest Weather Forecast

Radio 4 Listings for 16 – 22 May 2015 Page 1 of 17 SATURDAY 16 MAY 2015 SAT 06:57 Weather (b05tbnhj) Assistant Producer: Hannah Newton The latest weather forecast. SAT 00:00 Midnight News (b05tbngy) A Somethin' Else production for BBC Radio 4. The latest national and international news from BBC Radio 4. Followed by Weather. SAT 07:00 Today (b05v6cyd) Morning news and current affairs. Including Sports Desk, SAT 11:00 The Week in Westminster (b05v6cyn) Thought for the Day and Weather. Steve Richards of The Independent takes soundings on why SAT 00:30 Peter Moore - The Weather Experiment Labour lost the general election and the task facing its next (b05tq3y6) leader. How important are 'one nation' policies to the Prognostications and Forecasts SAT 09:00 Saturday Live (b05v6cyg) Conservatives? And how does it feel to arrive at Westminster Chris Tarrant for the SNP? The first forecasts prove controversial among the scientific community, and Robert FitzRoy's reputation is threatened. Presented by Richard Coles and Aasmah Mir. Editor: Peter Mulligan. Peter Moore's vivid account of the 19th century quest to Chris Tarrant has been a household staple since the mid 70s understand the weather. when he shook up Saturday mornings with children's TV series SAT 11:30 From Our Own Correspondent (b05tbnhl) Tiswas. He went on to do Capital Radio breakfast show and was Stranded at Sea Concluded by Tim McMullan. the presenter of ground breaking quiz show Who wants to be a Millionaire, which ran for 15 years, presenting many other Around the world. Today - another migrants crisis: aid workers Abridged by Sara Davies programmes along the way. -

Indirect Defensive Responses to Hostile Questions in British Broadcastnews Interviews

Dangjie Ji-Indirect Defensive Responsesto Hostile Questions In British BroadcastNews Interviews INDIRECT DEFENSIVE RESPONSES TO HOSTILE QUESTIONS IN BRITISH BROADCAST NEWS INTERVIEWS (2 Volumes) (Vol. 2) Dangjie Ji PhD University of York Centre of Communication Studies December2008 TJIo ML 2ý Dangjie Ji-Indirect Defensive Responsesto Hostile Questions In British BroadcastNews Interviews TABLE OF CONTENTS Volume 2 Cover (Vol. 2) 312 Table of Contents (Vol. 2) 313 Appendices Appendix A: Transcript Symbols in this thesis 314 Appendix B: Data Transcriptions for this thesis 320 Notes 568 Bibliography 570 313 Dangjie Ji-Indirect Defensive Responsesto Hostile Questions In British BroadcastNews Interviews APPENDICES Appendix A: Transcription rules in this thesis 1. Transcript Symbols: [ Separateleft squarebrackets, one above the other on two [ successivelines with utterancesby different speakers,indicates a point of overlap onset, whether at the start of an utterance or later. ] Separateright squarebrackets, one above the other on two ] successivelines with utterancesby different speakers indicates a point at which two overlapping utterances both end, where one ends while the other continues, or simultaneous moments in overlapswhich continue. { Thesesymbol are used to mark overlapping when more than two } persons are talking at the same time. Similar to the symbols of [ ], { marks the beginning of the overlapping, and } marks the end of overlapping. = Equal signs indicate `latching', i. e. without break or silence between utterancesbefore and after the sign. They are used in two circumstances: a) When indicating `latching' of utterancesbetween two different speakers,they come in pairs-one at the end of a line and another at the start of the next line or one shortly thereafter. -

Report Calls for 'Spring Clean' on Compliance Page 2 DG Visits Teams in Pakistan and Afghanistan Page 4 What Th

P H otograp 30·03·10 Week 13 THE BBC NEWSPAPER explore.gateway.bbc.co.uk/ariel H: mark a bassett THE BOAT RACE is ◆back on the BBC, and the production team is ready for the off. L-R are Séan Hughes, Michael Jackson, Paul Davies, Stephen Lyle and Jenny Hackett. Page 5 ROWERS RETURN ◆ Report calls for ◆ DG visits teams in ◆ What they did next - ‘spring clean’ on Pakistan and former staff on life compliance Page 2 Afghanistan Page 4 after the BBC Pages 8-9 > NEWS 2-4 WEEK AT WORK 7 OPINION 10 MAIL 11 JOBS 14 GREEN ROOM 16 < 216 News aa 00·00·08 30·03·10 NEWS BITES a Clearer compliance THE BBC Trust has extended the timetable for its review of the Gaelic service BBC Alba. Originally due to complete ahead of digital Room 2316, White City still needed in A&M switchover in central and northern 201 Wood Lane, London W12 7TS Scotland in April 2010, the review 020 8008 4228 by Cathy Loughran vation has survived and that ‘there is no evidence now will conclude after the trust has Editor that programmes which ought to be made are published its final view on what the Candida Watson 02-84222 ‘SIGNIFICANT CULTURAL CHANGES’ have taken not being made’. future strategy for the BBC ought Deputy editor place in Audio & Music since the Ross/Brand af- Trustee Alison Hastings said there had been to be, currently due later this year. fair, but tighter rules haven’t stifled risk-taking in clear evidence of change after ‘an extremely seri- Cathy Loughran 02-27360 programmes, an independent review has found.