***PAPER.Cwk (WP)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Framework for Embedded Digital Musical Instruments

A Framework for Embedded Digital Musical Instruments Ivan Franco Music Technology Area Schulich School of Music McGill University Montreal, Canada A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. © 2019 Ivan Franco 2019/04/11 i Abstract Gestural controllers allow musicians to use computers as digital musical instruments (DMI). The body gestures of the performer are captured by sensors on the controller and sent as digital control data to a audio synthesis software. Until now DMIs have been largely dependent on the computing power of desktop and laptop computers but the most recent generations of single-board computers have enough processing power to satisfy the requirements of many DMIs. The advantage of those single-board computers over traditional computers is that they are much smaller in size. They can be easily embedded inside the body of the controller and used to create fully integrated and self-contained DMIs. This dissertation examines various applications of embedded computing technologies in DMIs. First we describe the history of DMIs and then expose some of the limitations associated with the use of general-purpose computers. Next we present a review on different technologies applicable to embedded DMIs and a state of the art of instruments and frameworks. Finally, we propose new technical and conceptual avenues, materialized through the Prynth framework, developed by the author and a team of collaborators during the course of this research. The Prynth framework allows instrument makers to have a solid starting point for the de- velopment of their own embedded DMIs. -

B Ienna Le Des M Usiq Ues Exp Lo Ra to Ires

Biennale des musiques explo ratoires DU 14 MARS AU 4 AVRIL P.2 P.3 14 MARS — 14H & 16H30 14 & 15 MARS 15 MARS 15 MARS — 18H Kurt Schwitters, Sonate 21 MARS — 20H30 SALLE DU BALLET PARVIS DE L’AUDITORIUM PERFOMANCE — 12H15 GRANDE SALLE in Urlauten, avec cadence GRANDE SALLE ATELIER — 14H À 17H de Georges Aperghis Comme La Bulle BAS-ATRIUM Morciano, Charlie Chaplin, “The Hynkel Le Papillon Noir Speech” à la radio -Environnement Veggie Orchestra Dufourt, Ravel Benjamin de La Fuente, Bypass → Tarif plein : 10€ / Tarif réduit : 5€ SON PRIMORDIAL THEÂTRE DE LA RENAISSANCE, OULLINS DU 16 AU 20 MARS — 20H PETITE SALLE Tourniquet Installée pour toute la durée Orchestre national de Lyon Playtronica Lara Morciano, Riji, AUDITORIUM du week-end, La Bulle - Un concert suivi d'un déjeuner création mondiale -ORCHESTRE Environnement accueillera et d'un atelier à expérimenter Ensemble Multilatérale NATIONAL DE LYON de courtes formes artistiques Hugues Dufourt, Ur-Geräusch en famille qui fait chanter les fruits Maurice Ravel, Boléro Les Métaboles David Jisse, conception, voix, et des ateliers pour petits et grands. et les légumes. Yann Robin, musique 13 MARS – 20H → Gratuit ! → Tarifs : de 8 à 39€ échantillons et électronique → Gratuit ! Yannick H aenel, livret GRANDE SALLE Kasper T. Toeplitz, basse Elise Chauvin, actrice-chanteuse 14 & 15 MARS — 16H30 et percussions 15 MARS — 11H → Tarifs : de 5 à 25€ SALLE PROTON Quintette pour → Tarif plein : 8€ / Tarif réduit : 5€ GRANDE SALLE ombre et LE SUCRE Marie Nachury, texte, chant et jeu 24 MARS — 20H Leading -

Morrie Gelman Papers, Ca

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8959p15 No online items Morrie Gelman papers, ca. 1970s-ca. 1996 Finding aid prepared by Jennie Myers, Sarah Sherman, and Norma Vega with assistance from Julie Graham, 2005-2006; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé. UCLA Library Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA, 90095-1575 (310) 825-4988 [email protected] ©2016 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Morrie Gelman papers, ca. PASC 292 1 1970s-ca. 1996 Title: Morrie Gelman papers Collection number: PASC 292 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Language of Material: English Physical Description: 80.0 linear ft.(173 boxes and 2 flat boxes ) Date (inclusive): ca. 1970s-ca. 1996 Abstract: Morrie Gelman worked as a reporter and editor for over 40 years for companies including the Brooklyn Eagle, New York Post, Newsday, Broadcasting (now Broadcasting & Cable) magazine, Madison Avenue, Advertising Age, Electronic Media (now TV Week), and Daily Variety. The collection consists of writings, research files, and promotional and publicity material related to Gelman's career. Physical location: Stored off-site at SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact UCLA Library Special Collections for paging information. Creator: Gelman, Morrie Restrictions on Access Open for research. STORED OFF-SITE AT SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact UCLA Library Special Collections for paging information. Restrictions on Use and Reproduction Property rights to the physical object belong to the UC Regents. Literary rights, including copyright, are retained by the creators and their heirs. -

Serge Gainsbourg (1928–1991), the Greatest French Songwriter of the 1960S and 1970S, Was As Famous for His Decadent Life and Cynical Wit As for the Songs He Sang

Serge Gainsbourg (1928–1991), the greatest French songwriter of the 1960s and 1970s, was as famous for his decadent life and cynical wit as for the songs he sang. He made a career out of writing clever, provocative lyrics, recording many of them himself and giving others to his many famous friends and lovers to sing. His theatrical rudeness and outrageous provocations made him infamous and beloved in France. Gainsbourg was born in Paris, along with his twin sister Liliane, on April 2, 1928. His birth name was Lucien Ginsburg. His parents, Joseph and Olia Ginsburg, were Jewish immigrants who had fled the Ukraine around the time of the Russian Revolution. Joseph was a talented pianist in theaters and clubs in Paris. He taught his son and daughter piano, beginning when they were four years old. Lucien became interested in painting, so his parents sent him to art school in the Montmartre neighborhood of Paris. In 1945 Gainsbourg enrolled in the prestigious art school École Supérieure Des Beaux Arts, to pursue painting. Two years later he also enrolled in a music school while continuing his art studies. Joseph Ginsburg began passing some of his piano playing gigs on to his son. As the young Gainsbourg got more work in nightclubs, he gave up painting, frustrated that he was not a genius at it. He joined France's songwriters' society in 1954 and registered his first six songs. For his new career, he renamed himself. He had never liked his first name. "He thought it was a loser's name." Serge, he thought, sounded more Russian. -

Sooloos Collections: Advanced Guide

Sooloos Collections: Advanced Guide Sooloos Collectiions: Advanced Guide Contents Introduction ...........................................................................................................................................................3 Organising and Using a Sooloos Collection ...........................................................................................................4 Working with Sets ..................................................................................................................................................5 Organising through Naming ..................................................................................................................................7 Album Detail ....................................................................................................................................................... 11 Finding Content .................................................................................................................................................. 12 Explore ............................................................................................................................................................ 12 Search ............................................................................................................................................................. 14 Focus .............................................................................................................................................................. -

2016-Program-Book-Corrected.Pdf

A flagship project of the New York Philharmonic, the NY PHIL BIENNIAL is a wide-ranging exploration of today’s music that brings together an international roster of composers, performers, and curatorial voices for concerts presented both on the Lincoln Center campus and with partners in venues throughout the city. The second NY PHIL BIENNIAL, taking place May 23–June 11, 2016, features diverse programs — ranging from solo works and a chamber opera to large scale symphonies — by more than 100 composers, more than half of whom are American; presents some of the country’s top music schools and youth choruses; and expands to more New York City neighborhoods. A range of events and activities has been created to engender an ongoing dialogue among artists, composers, and audience members. Partners in the 2016 NY PHIL BIENNIAL include National Sawdust; 92nd Street Y; Aspen Music Festival and School; Interlochen Center for the Arts; League of Composers/ISCM; Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts; LUCERNE FESTIVAL; MetLiveArts; New York City Electroacoustic Music Festival; Whitney Museum of American Art; WQXR’s Q2 Music; and Yale School of Music. Major support for the NY PHIL BIENNIAL is provided by The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, The Fan Fox and Leslie R. Samuels Foundation, and The Francis Goelet Fund. Additional funding is provided by the Howard Gilman Foundation and Honey M. Kurtz. NEW YORK CITY ELECTROACOUSTIC MUSIC FESTIVAL __ JUNE 5-7, 2016 JUNE 13-19, 2016 __ www.nycemf.org CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 4 DIRECTOR’S WELCOME 5 LOCATIONS 5 FESTIVAL SCHEDULE 7 COMMITTEE & STAFF 10 PROGRAMS AND NOTES 11 INSTALLATIONS 88 PRESENTATIONS 90 COMPOSERS 92 PERFORMERS 141 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS THE NEW YORK PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA THE AMPHION FOUNDATION DIRECTOR’S LOCATIONS WELCOME NATIONAL SAWDUST 80 North Sixth Street Brooklyn, NY 11249 Welcome to NYCEMF 2016! Corner of Sixth Street and Wythe Avenue. -

The Underrepresentation of Female Personalities in EDM

The Underrepresentation of Female Personalities in EDM A Closer Look into the “Boys Only”-Genre DANIEL LUND HANSEN SUPERVISOR Daniel Nordgård University of Agder, 2017 Faculty of Fine Art Department of Popular Music There’s no language for us to describe women’s experiences in electronic music because there’s so little experience to base it on. - Frankie Hutchinson, 2016. ABSTRACT EDM, or Electronic Dance Music for short, has become a big and lucrative genre. The once nerdy and uncool phenomenon has become quite the profitable business. Superstars along the lines of Calvin Harris, David Guetta, Avicii, and Tiësto have become the rock stars of today, and for many, the role models for tomorrow. This is though not the case for females. The British magazine DJ Mag has an annual contest, where listeners and fans of EDM can vote for their favorite DJs. In 2016, the top 100-list only featured three women; Australian twin duo NERVO and Ukrainian hardcore DJ Miss K8. Nor is it easy to find female DJs and acts on the big electronic festival-lineups like EDC, Tomorrowland, and the Ultra Music Festival, thus being heavily outnumbered by the go-go dancers on stage. Furthermore, the commercial music released are almost always by the male demographic, creating the myth of EDM being an industry by, and for, men. Also, controversies on the new phenomenon of ghost production are heavily rumored among female EDM producers. It has become quite clear that the EDM industry has a big problem with the gender imbalance. Based on past and current events and in-depth interviews with several DJs, both female and male, this paper discusses the ongoing problems women in EDM face. -

The Passage of the Comic Book to the Animated Film: the Case of The

THE PASSAGE OF THE COMIC BOOK TO THE ANIMATED FILM: THE CASE OF THE SMURFS Frances Novier Baldwin, B.A. Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 2011 APPROVED: Marie-Christine Koop, Major Professor and Chair of the Department of Foreign Languages and Literatures Christophe Chaguinian, Committee Member Lawrence Williams, Committee Member James D. Meernik, Acting Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Baldwin, Frances Novier. The Passage of the Comic Book to the Animated Film: The Case of the Smurfs. Master of Arts (French), August 2011, 56 pp., bibliography, 31 titles. The purpose of this study is to explore the influence of history and culture on the passage of the comic book to the animated film. Although the comic book has both historical and cultural components, the latter often undergoes a cultural shift in the animation process. Using the Smurfs as a case study, this investigation first reviews existing literature pertaining to the comic book as an art form, the influence of history and culture on Smurf story plots, and the translation of the comic book into a moving picture. This study then utilizes authentic documents and interviews to analyze the perceptions of success and failure in the transformation of the Smurf comic book into animation: concluding that original meaning is often altered in the translation to meet the criteria of cultural relevance for the new audiences. Copyright 2011 By Frances Novier Baldwin ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am particularly grateful to Dr. Marie-Christine Koop for suggesting the topic for my thesis. For their instruction and guidance, I am also obliged to Drs. -

Elena Poniatowska Engalanará Festival Celebrate Mexico Now

Publication Date The New York Times 9/13/13 Flavorpill 9/17/13 Informador 8/16/13 Yareah Magazine 8/17/13 La Jornada 9/12/13 El Diario 9/6/13 Americas Society 9/12/13 The New York Times, Event Pick >> 09/13/13 >> A treat since 2004, this annual feast of music, dance, literature and film offers events mixing the traditional with the contemporary around New York City — many of which are free. The musical fare includes a concert of contemporary songs infused with traditional sounds by the New York group Radio Jarocho and others on Saturday at 11 p.m. at Le Poisson Rouge, 158 Bleecker Street, near Thompson Street, Greenwich Village; $20. On Sept. 21, at the Schimmel Center for the Arts, Pace University, 3 Spruce Street, Lower Manhattan, Mr. Ho’s Orchestrotica, from Boston, will play pop music from the ’50s and ’60s by the Mexican composer Juan García Esquivel, who died in 2004 at 83. Tickets are $35. The festival, running through Sept. 21, includes more than music, though. On Saturday at 7:30 p.m. at the Center for Performance Research, 361 Manhattan Avenue, in Bushwick, Brooklyn, the dancer Geraldine Cardiel will perform “Chronicles of Skin”; $15. And on Wednesday at 7 p.m., a free discussion on contemporary Mexican theater at the King Juan Carlos I of Spain Center at New York University, 53 Washington Square South, Greenwich Village, will feature the Mexican playwrights Bárbara Colio and Elena Guiochins, and Lydia Margules, artistic director of Museo Deseo Escena, a theater company in Mexico. -

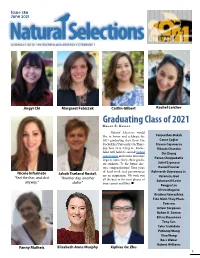

Graduating Class of 2021 M EGAN E

Issue !"# June $#$! A NEWSLETTER OF THE ROCKEFELLER UNIVERSITY COMMUNITY Jingyi Chi Margaret Fabiszak Caitlin Gilbert Rachel Leicher Graduating Class of 2021 M EGAN E . KELLEY Natural Selections would like to honor and celebrate the Sanjeethan Baksh 2021 graduating class from !e Caner Çağlar Rockefeller University. On !urs- Steven Cajamarca day, June 10 at 2:30 p.m., Rocke- Vikram Chandra feller will hold its second virtual Du Cheng convocation and confer doctorate Pavan Choppakatla degrees upon thirty-three gradu- ate students. To the future doc- Juliel Espinosa tors, congratulations! Your years Daniel Firester Rohiverth Guarecuco Jr. Nicole Infarinato Jakob Træland Rostøl, of hard work and perseverance are an inspiration. We wish you “Feel the fear, and do it “Another day, another Veronica Jové all the best in the next phases of Solomon N Levin anyway.” dollar” your careers and lives. n Fangyu Liu Olivia Maguire Kristina Navrazhina Tiên Minh Thủy Phan- Everson Artem Serganov Rohan R. Soman Elitsa Stoyanova Tony Sun Taku Tsukidate Putianqi Wang Xiao Wang Ross Weber Robert Williams Fanny Matheis Elisabeth Anne Murphy Xiphias Ge Zhu ! Editorial Board Megan Elizabeth Kelley Editor-in-Chief and Managing Editor, Communication Anna Amelianchik Associate Editor Nicole Infarinato Editorial Assistant, Copy Editor, Distribution Evan Davis Copy Editor, Photographer-in-Residence PHOTO COURTESY OF METROGRAPH PICTURES Melissa Jarmel Copy Editor, Website Tra!c Sisters with Transistors Audrey Goldfarb LANA NORRIS Copy Editor, Webmaster, Website Design Women have o"en been overlooked Barron built her own circuitry, and Laurie Jennifer Einstein, Emma Garst in the history of electronic music. !eir Spiegel programmed compositional so"- Copy Editors mastery of new technology and alien ware for Macs. -

Diehl Cv 2019

! " Biography 2019" BORN:" 1949 " Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA" EDUCATION: 1976 M.A. San Francisco State University, CA" 1973 B.A. California State University Hayward, CA " 1970 Diablo Valley College, Pleasant Hill, CA" SOLO EXHIBITIONS: 2020 Dolby Chadwick Gallery, San Francisco, CA" 2018 Solo Exhibition, Fresno Museum of Art, Fresno, CA - July to October" Dolby Chadwick Gallery, San Francisco, CA" 2015 Dolby Chadwick Gallery, San Francisco, CA" 2013 Dolby Chadwick Gallery, San Francisco, CA" 2011 Dolby Chadwick Gallery, San Francisco, CA " 2007 Sonoma Valley Museum of Art, Sonoma, CA " Hackett-Freedman Gallery, San Francisco, CA " 2004 Hunsaker/Schlesinger Gallery, Santa Monica, CA" 2003 Hackett-Freedman Gallery, San Francisco, CA" 2001 Hackett-Freedman Gallery, San Francisco, CA" 1998 Hackett-Freedman Gallery, San Francisco, CA" 1997 Modernism, San Francisco, CA" 1995 Fletcher Gallery, Santa Fe, NM" 1994 Modernism, San Francisco, CA" #" 1993 Modernism, San Francisco, CA " " 1990 Jeremy Stone Gallery, San Francisco, CA" 1989 University of Pacific, Stockton, CA" #" 1988 Jeremy Stone Gallery, San Francisco, CA" www.guydiehl.com Guy Diehl biography 2016 - page !1 Magic Theater, Fort Mason Art Center, San Francisco, CA" 1987 Hunsaker/Schlesinger Gallery, Los Angeles, CA" 1986 Jeremy Stone Gallery, San Francisco, CA" The Lurie Company, San Francisco, CA" 1984 Hank Baum Gallery, San Francisco, CA" " 1982 Hank Baum Gallery, San Francisco, CA" 1981 Shepard Art Gallery, University of Nevada, Reno, NV" 1980 Hank Baum Gallery, San Francisco, CA" -

Coloring the Gap Between Canoga Park and Calabasas

West Valley New Hotel Proposed - See Page 6 Local Artist Playhouse Hangs With Finds Temporary Cartoon New Home + Characters More Theatre See page 3 See Page 9 ValleyVolume 34, Issue 52 A CompendiousVantage Source of Information February 21, 2019 NEWS IN BRIEF Coloring the Gap Between It Snowed Today! Canoga Park and Calabasas As if the recent A crayon is such a little thing. rainstorms haven’t been But yellow can create a sun. Blue can crazy enough, sights fill in a sky. A whole box can make a rainbow. of snow were reported But here in our backyard, a crayon can in Calabasas this be a big thing - if you don’t have any. Thursday, February 21. At Hart Street Elementary School in Calabasas resident and Canoga Park, most of the kids are on the free actor Jerry O’ Connell lunch program. They come from homes that took to his Instagram are barely scraping by. There is never enough stories to record the money for rent, food, clothes. Crayons are unprecedented weather way down the list. event, pointing out the shocking flurries. Weather stations Enter a partnership between the have forecasted that with the record low temperatures, Calabasas County Club and Crayon snowfall would drop to lower levels but no one could have Collection, a non-profit art-centered predicated we would see snowflakes in Calabasas. Yet, in organization. effect today through Friday morning is a freeze watch that Anastasia Using crayons from could see temperatures drop to between 29 and 32 degrees. Alexander, Crayon Collection to While we sadly can’t cross our fingers for upcoming snow Clubhouse Manager create art, above.