Kirk Douglas and Stanley Kubrick

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hanks, Spielberg Tops in U.S. Army Europe Hollywood Poll

Hanks, Spielberg tops in U.S. Army Europe Hollywood poll June 8, 2011 By U.S. Army Europe Public Affairs HEIDELBERG, Germany -- “Band of Brothers” narrowly edged “Saving Private Ryan” in a two-week U.S. Army Europe Web poll asking the public to select their five favorite Related Links films portraying U.S. Soldiers in Europe. Poll Results The final tally for the top spot was 128 votes to 126, revealing the powerful appeal Tom U.S. Army Europe Facebook Hanks and Steven Spielberg hold among poll participants in detailing the experiences of U.S. Army Europe Twitter WWII veterans. U.S. Army Europe YouTube The two movies were both the result of collaborations by the Hollywood A-listers. U.S. Army Europe Flickr Rounding out the top five was “The Longest Day,” a 1962 drama starring John Wayne about the events of D-Day; “Patton,” directed by Francis Ford Coppola in 1970 and starring George C. Scott as the famed American general; and “A Bridge Too Far,” a 1977 film starring Sean Connery about the failed Operation Market- Garden. The poll received a total of 814 votes and was based on the realism, entertainment value and overall quality of 20 movies featuring the U.S. Army in Europe. Some of Hollywood's biggest stars throughout history - Elvis, Clint Eastwood, Gary Cooper, Bill Murray, Gene Hackman – have all taken turns on the big screen portraying U.S. Soldiers in Europe. But to participants of the U.S. Army Europe poll, it was the lesser-known “Band of Brothers” in Easy Company who were most endearing. -

LIG. SUED 011ADS FORKENEDY Fl

practice MIMS at a. iu.L the desert. The film opened }LIG. SUED 011 ADS ,here yesterday at the Coronet 1, Titeitier. • FORKENEDY Fl Protest Explained Charles Boasberg, president of National General Pictures 'Makers of 'Executive Action' Corporation,' through which the film is being released, Ask Cancellation Damages said that if television stations ... were allowed to approve or disapprove of television com- By LOUIS CALTA mercials "no one will he able The distributor of "Execu, to make a motion picture • tive Action," the movie by without first clearing its sub- Dalton Trumbo about a "con- , ject matter with television , spiracy" to assassinate Pres- . executives." •. :ident Kennedy, filed a $1.5- Edward Lewis, producer of ' Million breach-of-agreement the film, which co-stars Burt suit yesterday morning in Lancaster, the. late. Robert - New York State Supreme Ryan and Will Geer, called , Court against the National • N.B.C,'s action television 'Broadcasting Company for censorship. canceling a television com- Ira Teller, director of ad- rnercial promoting the film. vertising and publicity for Arthur Watson, executive --, National General Pictures, ex- „Vice president of N.B.C. and plained that after N.B.C. had general manager of WNBC- turned down the commercial , TV, said that the spot adver- "We went to the American tisement was turned down Broadcasting Company and "on the basis of not meeting , the Columbia Broadcasting N.B.C.'s standards. The vio- System to seek available ,lence portrayed in the time, but were told that none commercial was excessive was available." • and was done in such detail The distributing Company, as to be instructional or to however, was successful in invite imitation," he said. -

Modus Operandi Films and High Point Media Group Present

Modus Operandi Films and High Point Media Group Present A film by Craig McCall Worldwide Sales: High Point Media Group Contact in Cannes: Residences du Grand Hotel, Cormoran II, 3 rd Floor: Tel: +33 (0) 4 93 38 05 87 London Contact: Tel: +44 20 7424 6870. Fax +44 20 7435 3281 [email protected] CAMERAMAN: The Life & Work of Jack Cardiff page 1 of 27 © Modus Operandi Films 2010 HP PRESS KIT CAMERAMAN: The Life and Work of Jack Cardiff www.jackcardiff.com Contents: - Film Synopsis p 3 - 10 Facts About Jack p 4 - Jack Cardiff Filmography p 5 - Quotes about Jack p 6 - Director’s Notes p 7 - Interviewee’s p 8 - Bio’s of Key Crew p10 - Director's Q&A p14 - Credits p 19 CAMERAMAN: The Life & Work of Jack Cardiff page 2 of 27 © Modus Operandi Films 2010 HP PRESS KIT CAMERAMAN : The Life and Work of Jack Cardiff A Documentary Feature Film Logline: Celebrating the remarkable nine decade career of legendary cinematographer, Jack Cardiff, who provided the canvas for classics like The Red Shoes and The African Queen . Short Synopsis: Jack Cardiff’s career spanned an incredible nine of moving picture’s first ten decades and his work behind the camera altered the look of films forever through his use of Technicolor photography. Craig McCall’s passionate film about the legendary cinematographer reveals a unique figure in British and international cinema. Long Synopsis: Cameraman illuminates a unique figure in British and international cinema, Jack Cardiff, a man whose life and career are inextricably interwoven with the history of cinema spanning nine decades of moving pictures' ten. -

A Labour History of Irish Film and Television Drama Production 1958-2016

A Labour History of Irish Film and Television Drama Production 1958-2016 Denis Murphy, B.A. (Hons), M.A. (Hons) This thesis is submitted for the award of PhD January 2017 School of Communications Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Dublin City University Supervisor: Dr. Roddy Flynn I hereby certify that this material, which I now submit for assessment on the programme of study leading to the award of PhD, is entirely my own work, and that I have exercised reasonable care to ensure that the work is original, and does not to the best of my knowledge breach any law of copyright, and has not been taken from the work of others save and to the extent that such work has been cited and acknowledged within the text of my work. Signed: ___________________________________ (Candidate) ID No.: 81407637 Date: _______________ 2 Table of Contents Introduction ....................................................................................................................................... 12 The research problem ................................................................................................................................. 14 Local history, local Hollywood? ............................................................................................................... 16 Methodology and data sources ................................................................................................................ 18 Outline of chapters ....................................................................................................................................... -

It's a Conspiracy

IT’S A CONSPIRACY! As a Cautionary Remembrance of the JFK Assassination—A Survey of Films With A Paranoid Edge Dan Akira Nishimura with Don Malcolm The only culture to enlist the imagination and change the charac- der. As it snows, he walks the streets of the town that will be forever ter of Americans was the one we had been given by the movies… changed. The banker Mr. Potter (Lionel Barrymore), a scrooge-like No movie star had the mind, courage or force to be national character, practically owns Bedford Falls. As he prepares to reshape leader… So the President nominated himself. He would fill the it in his own image, Potter doesn’t act alone. There’s also a board void. He would be the movie star come to life as President. of directors with identities shielded from the public (think MPAA). Who are these people? And what’s so wonderful about them? —Norman Mailer 3. Ace in the Hole (1951) resident John F. Kennedy was a movie fan. Ironically, one A former big city reporter of his favorites was The Manchurian Candidate (1962), lands a job for an Albu- directed by John Frankenheimer. With the president’s per- querque daily. Chuck Tatum mission, Frankenheimer was able to shoot scenes from (Kirk Douglas) is looking for Seven Days in May (1964) at the White House. Due to a ticket back to “the Apple.” Pthe events of November 1963, both films seem prescient. He thinks he’s found it when Was Lee Harvey Oswald a sleeper agent, a “Manchurian candidate?” Leo Mimosa (Richard Bene- Or was it a military coup as in the latter film? Or both? dict) is trapped in a cave Over the years, many films have dealt with political conspira- collapse. -

Pre-Operative Risk Stratification

Kirsten Wennermark, MD University of Colorado Surgical Resident PGY-3 Over 80 Kirk Douglas: 12/9/1916 Betty White: 1/17/22 George H.W. Bush: 6/12/1924 Jimmy Carter: 10/1/1924 Angela Lansbury: 10/16/1925 Dick Van Dyke: 12/13/1925 Jerry Lewis: 3/16/1926 Andy Griffith: 6/1/1926 Jerry Stiller: 6/8/1927 Mel Brooks: 6/28/1928 Edward Asner: 11/15/29 Gene Hackman: 1/30/1930 Clint Eastwood: 5/31/1930 Sean Connery: 8/25/1930 Doris Roberts: 11/4/1930 Robert Duvall: 1/5/1931 James Earl Jones: 1/17/1931 William Shatner: 3/22/1931 Case Presentation 81y/o VA patient presented with shortness of breath and decreased exercise tolerance. Normal exercise routine consisted of daily weight-lifting and swimming laps for 2 hours. Reduced exercise tolerance to only 1.5 hours of swim laps daily. PMH: well-controlled HTN PSH: Elbow surgery at age 14 Labs: initial H/H 6.0/17.1 (6/17/11) -> 10/28.1 (11/22/11) Workup resulted in findings of: autoimmune hemolytic anemia and an enlarged spleen Referred to surgery for Laparoscopic Splenectomy Risk stratification Age Eyeball test Comorbidities Katz Index Nutritional status Edmonton Frail Functionality Scale (EFS) Type of Surgery Comprehensive ASA Classification geriatric assessment (CGA) Eyeball Test Appearance Stated age, older, younger Mobility Walking unassisted, cane, walker, wheelchair Other supplemental equipment Oxygen tank Frailty Chronologic age does not always reflect physiologic age, and elderly people have a range of physiologic status that varies from robust to frail. Describes an elderly person who is at heightened vulnerability to adverse health status change because of multisystem reduction in reserve capacity. -

Michael Gold & Dalton Trumbo on Spartacus, Blacklist Hollywood

LH 19_1 FInal.qxp_Left History 19.1.qxd 2015-08-28 4:01 PM Page 57 Michael Gold & Dalton Trumbo on Spartacus, Blacklist Hollywood, Howard Fast, and the Demise of American Communism 1 Henry I. MacAdam, DeVry University Howard Fast is in town, helping them carpenter a six-million dollar production of his Spartacus . It is to be one of those super-duper Cecil deMille epics, all swollen up with cos - tumes and the genuine furniture, with the slave revolution far in the background and a love tri - angle bigger than the Empire State Building huge in the foreground . Michael Gold, 30 May 1959 —— Mike Gold has made savage comments about a book he clearly knows nothing about. Then he has announced, in advance of seeing it, precisely what sort of film will be made from the book. He knows nothing about the book, nothing about the film, nothing about the screenplay or who wrote it, nothing about [how] the book was purchased . Dalton Trumbo, 2 June 1959 Introduction Of the three tumultuous years (1958-1960) needed to transform Howard Fast’s novel Spartacus into the film of the same name, 1959 was the most problematic. From the start of production in late January until the end of all but re-shoots by late December, the project itself, the careers of its creators and financiers, and the studio that sponsored it were in jeopardy a half-dozen times. Blacklist Hollywood was a scary place to make a film based on a self-published novel by a “Commie author” (Fast), and a script by a “Commie screenwriter” (Trumbo). -

Boxoffice Barometer (March 6, 1961)

MARCH 6, 1961 IN TWO SECTIONS SECTION TWO Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents William Wyler’s production of “BEN-HUR” starring CHARLTON HESTON • JACK HAWKINS • Haya Harareet • Stephen Boyd • Hugh Griffith • Martha Scott • with Cathy O’Donnell • Sam Jaffe • Screen Play by Karl Tunberg • Music by Miklos Rozsa • Produced by Sam Zimbalist. M-G-M . EVEN GREATER IN Continuing its success story with current and coming attractions like these! ...and this is only the beginning! "GO NAKED IN THE WORLD” c ( 'KSX'i "THE Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents GINA LOLLOBRIGIDA • ANTHONY FRANCIOSA • ERNEST BORGNINE in An Areola Production “GO SPINSTER” • • — Metrocolor) NAKED IN THE WORLD” with Luana Patten Will Kuluva Philip Ober ( CinemaScope John Kellogg • Nancy R. Pollock • Tracey Roberts • Screen Play by Ranald Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer pre- MacDougall • Based on the Book by Tom T. Chamales • Directed by sents SHIRLEY MacLAINE Ranald MacDougall • Produced by Aaron Rosenberg. LAURENCE HARVEY JACK HAWKINS in A Julian Blaustein Production “SPINSTER" with Nobu McCarthy • Screen Play by Ben Maddow • Based on the Novel by Sylvia Ashton- Warner • Directed by Charles Walters. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents David O. Selznick's Production of Margaret Mitchell’s Story of the Old South "GONE WITH THE WIND” starring CLARK GABLE • VIVIEN LEIGH • LESLIE HOWARD • OLIVIA deHAVILLAND • A Selznick International Picture • Screen Play by Sidney Howard • Music by Max Steiner Directed by Victor Fleming Technicolor ’) "GORGO ( Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents “GORGO” star- ring Bill Travers • William Sylvester • Vincent "THE SECRET PARTNER” Winter • Bruce Seton • Joseph O'Conor • Martin Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents STEWART GRANGER Benson • Barry Keegan • Dervis Ward • Christopher HAYA HARAREET in “THE SECRET PARTNER” with Rhodes • Screen Play by John Loring and Daniel Bernard Lee • Screen Play by David Pursall and Jack Seddon Hyatt • Directed by Eugene Lourie • Executive Directed by Basil Dearden • Produced by Michael Relph. -

The Field Guide to Sponsored Films

THE FIELD GUIDE TO SPONSORED FILMS by Rick Prelinger National Film Preservation Foundation San Francisco, California Rick Prelinger is the founder of the Prelinger Archives, a collection of 51,000 advertising, educational, industrial, and amateur films that was acquired by the Library of Congress in 2002. He has partnered with the Internet Archive (www.archive.org) to make 2,000 films from his collection available online and worked with the Voyager Company to produce 14 laser discs and CD-ROMs of films drawn from his collection, including Ephemeral Films, the series Our Secret Century, and Call It Home: The House That Private Enterprise Built. In 2004, Rick and Megan Shaw Prelinger established the Prelinger Library in San Francisco. National Film Preservation Foundation 870 Market Street, Suite 1113 San Francisco, CA 94102 © 2006 by the National Film Preservation Foundation Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Prelinger, Rick, 1953– The field guide to sponsored films / Rick Prelinger. p. cm. Includes index. ISBN 0-9747099-3-X (alk. paper) 1. Industrial films—Catalogs. 2. Business—Film catalogs. 3. Motion pictures in adver- tising. 4. Business in motion pictures. I. Title. HF1007.P863 2006 011´.372—dc22 2006029038 CIP This publication was made possible through a grant from The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. It may be downloaded as a PDF file from the National Film Preservation Foundation Web site: www.filmpreservation.org. Photo credits Cover and title page (from left): Admiral Cigarette (1897), courtesy of Library of Congress; Now You’re Talking (1927), courtesy of Library of Congress; Highlights and Shadows (1938), courtesy of George Eastman House. -

October 9, 2012 (XXV:6) David Miller, LONELY ARE the BRAVE (1962, 107 Min)

October 9, 2012 (XXV:6) David Miller, LONELY ARE THE BRAVE (1962, 107 min) Directed by David Miller Screenplay by Dalton Trumbo Based on the novel, The Brave Cowboy, by Edward Abbey Produced by Edward Lewis Original Music by Jerry Goldsmith Cinematography by Philip H. Lathrop Film Editing by Leon Barsha Art Direction by Alexander Golitzen and Robert Emmet Smith Set Decoration by George Milo Makeup by Larry Germain, Dave Grayson, and Bud Westmore Kirk Douglas…John W. "Jack" Burns Gena Rowlands…Jerry Bondi Walter Matthau…Sheriff Morey Johnson Michael Kane…Paul Bondi Carroll O'Connor…Hinton William Schallert…Harry George Kennedy…Deputy Sheriff Gutierrez Karl Swenson…Rev. Hoskins William Mims…First Deputy Arraigning Burns Martin Garralaga…Old Man Lalo Rios…Prisoner Bill Bixby…Airman in Helicopter Bill Raisch…One Arm Table Tennis, 1936 Let's Dance, 1935 A Sports Parade Subject: Crew DAVID MILLER (November 28, 1909, Paterson, New Jersey – April Racing, and 1935 Trained Hoofs. 14, 1992, Los Angeles, California) has 52 directing credits, among them 1981 “Goldie and the Boxer Go to Hollywood”, 1979 “Goldie DALTON TRUMBO (James Dalton Trumbo, December 9, 1905, and the Boxer”, 1979 “Love for Rent”, 1979 “The Best Place to Be”, Montrose, Colorado – September 10, 1976, Los Angeles, California) 1976 Bittersweet Love, 1973 Executive Action, 1969 Hail, Hero!, won best writing Oscars for The Brave One (1956) and Roman 1968 Hammerhead, 1963 Captain Newman, M.D., 1962 Lonely Are Holiday (1953). He was blacklisted for many years and, until Kirk the Brave, 1961 Back Street, 1960 Midnight Lace, 1959 Happy Douglas insisted he be given screen credit for Spartacus was often to Anniversary, 1957 The Story of Esther Costello, 1956 Diane, 1951 write under a pseudonym. -

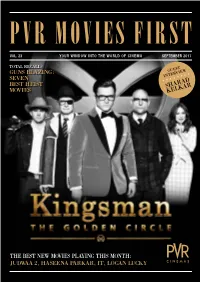

Sharad Kelkarguest INTERVIEW

PVR MOVIES FIRST VOL. 23 YOUR WINDOW INTO THE WORLD OF CINEMA SEPTEMBER 2017 TOTAL RECALL: guest GUNS BLAZING: interview SEVEN BEST HEIST SHARAD MOVIES KELKAR THE BEST NEW MOVIES PLAYING THIS MONTH: JUDwaa 2, HASEENA PARKAR, IT, LOGAN LUCKY GREETINGS ear Movie Lovers, Revisit “The Apartment , “ a classic romantic comedy directed by Billy Wilder . Here’s the September edition of Movies First, your exclusive window to the world of cinema. T ake a peek at the life and films of legendary lyricist and filmmaker Gulzar , and join us in wishing Hollywood This month is packed with high-octane thrillers. superstar Keanu Reeves a Happy Birthday. Watch the Kingsman spies match wits and strength We really hope you enjoy the issue. Wish you a fabulous with a secret enemy. Arjun Rampal portrays the dark month of movie watching. life of mafia don Arun Gawli in “Daddy,” while Shraddha Kapoor traces the journey of crime queen “Haseena Regards Parkar .” Ajay Devgn pulls off a daring 70s-style heist Gautam Dutta in “Baadshaho.” CEO, PVR Limited USING THE MAGAZINE We hope youa’ll find this magazine easy to use, but here’s a handy guide to the icons used throughout anyway. You can tap the page once at any time to access full contents at the top of the page. PLAY TRAILER SET REMINDER BOOK TICKETS SHARE PVR MOVIES FIRST PAGE 2 CONTENTS London’s top spies The Kingsman are back with a new adventure. Turn the pages to get a peek inside their new mission. Tap for... Tap for... Movie OF THE MONTH GUEST INTERVIEW Tap for.. -

Representations of Mental Illness in Women in Post-Classical Hollywood

FRAMING FEMININITY AS INSANITY: REPRESENTATIONS OF MENTAL ILLNESS IN WOMEN IN POST-CLASSICAL HOLLYWOOD Kelly Kretschmar, B.A. Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2007 APPROVED: Harry M. Benshoff, Major Professor Sandra Larke-Walsh, Committee Member Debra Mollen, Committee Member Ben Levin, Program Coordinator Alan B. Albarran, Chair of the Department of Radio, Television and Film Sandra L. Terrell, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Kretschmar, Kelly, Framing Femininity as Insanity: Representations of Mental Illness in Women in Post-Classical Hollywood. Master of Arts (Radio, Television, and Film), May 2007, 94 pp., references, 69 titles. From the socially conservative 1950s to the permissive 1970s, this project explores the ways in which insanity in women has been linked to their femininity and the expression or repression of their sexuality. An analysis of films from Hollywood’s post-classical period (The Three Faces of Eve (1957), Lizzie (1957), Lilith (1964), Repulsion (1965), Images (1972) and 3 Women (1977)) demonstrates the societal tendency to label a woman’s behavior as mad when it does not fit within the patriarchal mold of how a woman should behave. In addition to discussing the social changes and diagnostic trends in the mental health profession that define “appropriate” female behavior, each chapter also traces how the decline of the studio system and rise of the individual filmmaker impacted the films’ ideologies with regard to mental illness and femininity. Copyright 2007 by Kelly Kretschmar ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Chapter 1. INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................... 1 Historical Perspective ........................................................................ 5 Women and Mental Illness in Classical Hollywood ...............................