Final Proof #9184—Social Psychology Quarterly—Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

30 Rock and Philosophy: We Want to Go to There (The Blackwell

ftoc.indd viii 6/5/10 10:15:56 AM 30 ROCK AND PHILOSOPHY ffirs.indd i 6/5/10 10:15:35 AM The Blackwell Philosophy and Pop Culture Series Series Editor: William Irwin South Park and Philosophy X-Men and Philosophy Edited by Robert Arp Edited by Rebecca Housel and J. Jeremy Wisnewski Metallica and Philosophy Edited by William Irwin Terminator and Philosophy Edited by Richard Brown and Family Guy and Philosophy Kevin Decker Edited by J. Jeremy Wisnewski Heroes and Philosophy The Daily Show and Philosophy Edited by David Kyle Johnson Edited by Jason Holt Twilight and Philosophy Lost and Philosophy Edited by Rebecca Housel and Edited by Sharon Kaye J. Jeremy Wisnewski 24 and Philosophy Final Fantasy and Philosophy Edited by Richard Davis, Jennifer Edited by Jason P. Blahuta and Hart Weed, and Ronald Weed Michel S. Beaulieu Battlestar Galactica and Iron Man and Philosophy Philosophy Edited by Mark D. White Edited by Jason T. Eberl Alice in Wonderland and The Offi ce and Philosophy Philosophy Edited by J. Jeremy Wisnewski Edited by Richard Brian Davis Batman and Philosophy True Blood and Philosophy Edited by Mark D. White and Edited by George Dunn and Robert Arp Rebecca Housel House and Philosophy Mad Men and Philosophy Edited by Henry Jacoby Edited by Rod Carveth and Watchman and Philosophy James South Edited by Mark D. White ffirs.indd ii 6/5/10 10:15:36 AM 30 ROCK AND PHILOSOPHY WE WANT TO GO TO THERE Edited by J. Jeremy Wisnewski John Wiley & Sons, Inc. ffirs.indd iii 6/5/10 10:15:36 AM To pages everywhere . -

Two Family Members Die in I-80 Rollover

FRONT PAGE A1 www.tooeletranscript.com TUESDAY TOOELE RANSCRIPT Two local players T compete against each other at college level See A9 BULLETIN October 2, 2007 SERVING TOOELE COUNTY SINCE 1894 VOL. 114 NO. 38 50¢ Two family members die in I-80 rollover by Suzanne Ashe injured in the wreck. He was victims to the hospital. STAFF WRITER one of seven people who were Jose Magdeleno, 9, Yadira thrown from the vehicle when it Miranda, 5, and Amie Cano, Two members of the same rolled several times. 5, were all flown to Primary family died as a result of a The car was speeding when it Children’s Hospital. crash near Delle on I-80 Sunday drifted to the left before Cano- Gutierrez said the family may night. Magdeleno overcorrected to the have been coming back from According to Utah Highway right and the car went off the Wendover. Patrol Trooper Sgt. Robert road, Gutierrez said. All eastbound lanes were Gutierrez, the single-vehicle Cano-Magdeleno’s wife, closed for about an hour after rollover occurred at 7:20 p.m. Roxanna Guatalupe Miranda, the accident, and lane No. 2 was near mile post 69. 22, and the driver’s daugh- closed for about three hours. Gutierrez said alcohol was ter Emily Cano, 10 were killed. Gutierrez said no one in the a factor, and open containers Dalila Marisol Cano, 39, is in two-door 1988 Ford Escort was were found at the scene. critical condition. wearing a seat belt. Photo courtesy of Utah Highway Patrol The driver, Jose J. -

Cassette Books, CMLS,P.O

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 319 210 EC 230 900 TITLE Cassette ,looks. INSTITUTION Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped. PUB DATE 8E) NOTE 422p. AVAILABLE FROMCassette Books, CMLS,P.O. Box 9150, M(tabourne, FL 32902-9150. PUB TYPE Reference Materials Directories/Catalogs (132) --- Reference Materials Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC17 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Adults; *Audiotape Recordings; *Blindness; Books; *Physical Disabilities; Secondary Education; *Talking Books ABSTRACT This catalog lists cassette books produced by the National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped during 1989. Books are listed alphabetically within subject categories ander nonfiction and fiction headings. Nonfiction categories include: animals and wildlife, the arts, bestsellers, biography, blindness and physical handicaps, business andeconomics, career and job training, communication arts, consumerism, cooking and food, crime, diet and nutrition, education, government and politics, hobbies, humor, journalism and the media, literature, marriage and family, medicine and health, music, occult, philosophy, poetry, psychology, religion and inspiration, science and technology, social science, space, sports and recreation, stage and screen, traveland adventure, United States history, war, the West, women, and world history. Fiction categories includer adventure, bestsellers, classics, contemporary fiction, detective and mystery, espionage, family, fantasy, gothic, historical fiction, -

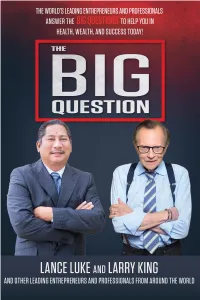

THE BIG QUESTION to Them

Copyright © 2018 CelebrityPress® LLC All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without prior written consent of the author, except as provided by the United States of America copyright law Published by CelebrityPress®, Orlando, FL. CelebrityPress® is a registered trademark. Printed in the United States of America. ISBN: 978-0-9991714-5-5 LCCN: 2018931599 This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information with regard to the subject matter covered. It is sold with the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering legal, accounting, or other professional advice. If legal advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional should be sought. The opinions expressed by the authors in this book are not endorsed by CelebrityPress® and are the sole responsibility of the author rendering the opinion. Most CelebrityPress® titles are available at special quantity discounts for bulk purchases for sales promotions, premiums, fundraising, and educational use. Special versions or book excerpts can also be created to fit specific needs. For more information, please write: CelebrityPress® 520 N. Orlando Ave, #2 Winter Park, FL 32789 or call 1.877.261.4930 Visit us online at: www.CelebrityPressPublishing.com CelebrityPress® Winter Park, Florida CONTENTS CHAPTER 1 QUESTIONS ARE MORE IMPORTANT THAN ANSWERS By Larry King .................................................................................... 13 CHAPTER 2 PUBLIC SPEAKING: HOW TO ACHIEVE MAXIMUM AUDIENCE ENGAGEMENT By Mohamed Isa .............................................................................. 23 CHAPTER 3 THE INTERVIEW THAT, SADLY, NEVER WAS By John Parks Trowbridge M.D., FACAM ..........................................31 CHAPTER 4 WHY DO THE BIG GET BIGGER? By Rebecca Crownover ...................................................................47 CHAPTER 5 THE KEYS TO SUCCESS By Patricia Delinois .......................................................................... -

Anser-50Th-History-Book.Pdf

ANALYTIC SERVICES INC. ANALYTIC SERVICES INC. Celebrating 50 Years a H i s t o r Y o f a n a lY t i C s e r v i C e s i n C . YEARS YEARS 1 9 5 8 - 2 0 0 8 1 9 5 8 - 2 0 0 8 PUBLIC SERVICE. PUBLIC TRUST. PUBLIC SERVICE. PUBLIC TRUST. Written By David Bounds The author thanks Tom Benjamin, Joan Zaorski, Mary Webb, Allifa Settles-Mitchell, Cathy Lee, Jack Butler, Mike Bowers, and Paul Higgins for their great assistance in bringing this project to fruition. Thanks as well to Harry Emlet, George Thompson, Steve Hopkins, Trina Powell, Christina Scott, and many other Analytic Services Inc. staff—past and present—who gave time, insight, and memories to this. As you will see on the next page… this was all about you. [ ii ] [ 111 ] ANALYTIC SERVICES INC. A History of An A ly t i c s e r v i c e s i n c . YEARS 1 9 5 8 - 2 0 0 8 PUBLIC SERVICE. PUBLIC TRUST. Dedicated to—in the words of the senior leadership over the life of the corporation so far—the “people, people, people” of Analytic Services Inc., for their efforts that have made this corporation, for their efforts that have helped make this Nation. [ iii ] ANALYTIC SERVICES INC. c e l e b r A t i n g 5 0 y e A r s YEARS 1 9 5 8 - 2 0 0 8 PUBLIC SERVICE. PUBLIC TRUST. [ iv ] ANALLYTICIC SERVIICES INC. -

Philip Hilder and Mark Zachary of Countrywide on Larry King Live

Larry King: Transcript Page 1 of 9 900% Penny Stocks Gainer “Killer White Teeth” Stocks that blow up overnight. Free reports. Join today. Dentists don't want you to know THIS teeth whitening secret. www.Stockpickss.com AmericanDermaSociety.org Get listed here Home | Larry King Interview Archives | Larry King Live Radio Archives | Listen to CNN Radio | CNN Radio Hourly News Update archives Interview with Sen. Barack Obama; Mortgage Crisis Affects Thousands of Homeowners Aired July 15, 2008 - 21:00 ET THIS IS A RUSH TRANSCRIPT. THIS COPY MAY NOT BE IN ITS FINAL FORM AND MAY BE UPDATED. LARRY KING, HOST: Tonight, Barack Obama sounds off right here on the magazine cover that created a firestorm. Some were outraged. Now it's his turn. (BEGIN VIDEO CLIP) SEN. BARACK OBAMA (D), PRESIDENTIAL CANDIDATE: I've seen and heard worse. (END VIDEO CLIP) KING: What does he think about being portrayed as a Muslim? (BEGIN VIDEO CLIP) OBAMA: I'm a Christian and I wasn't raised in a Muslim home and I pledge allegiance to the flag. (END VIDEO CLIP) KING: And then, foreclosure nightmare -- are you in danger of losing your home? Surprising confessions from a mortgage loan officer. And a former mortgage company worker forced to live out of her car. It's all right now on LARRY KING LIVE. We welcome to LARRY KING LIVE Senator Barack Obama, the presumptive Democratic presidential nominee. He made a major foreign policy address today in Washington. We'll get to that in a moment. But I've heard a lot of others comment on it. -

Larry King Book Pdf

Larry king book pdf Continue This article is about the TV presenter. For other purposes, see Larry King (disambiguation). American TV and Radio Host Larry KingKing in March 2017BornLawrence Harvey Seiger (1933-11-19) November 19, 1933 (age 86)Brooklyn, New York, U.S.EducationLafayette High SchoolOccupationRadio and television personalityYears active1957-presentSpouse (s)Freda Miller (m. 1952; ann. 1953) Annette Kay (m. 1961; div. 1961) Alain Akins (m. 1961; div. 1963, m. 1967; div. 1972) Mickey Sutphin (m. 1963; div. 1967) Sharon Lepore (m. 1976; div. 1983) Julie Alexander (m. 1989; div. 1992) Shaun Southwick (m. 1997; sep. 2019) Children7 Larry King ( Lawrence Harvey Seiger was born; November 19, 1933) is an American television and radio host whose work has been awarded awards, including two Peabody Awards, an Emmy Award and 10 Cable ACE Awards. King began as a local Florida journalist and radio interviewer in the 1950s and 1960s and gained notoriety since 1978 as host of The Larry King Show, an all-night nationwide call-up in a radio program heard about the mutual broadcasting system. From 1985 to 2010, he hosted the nightly program of Larry King's Live interview on CNN. From 2012 to 2020, he hosted Larry King on Hulu and RT America. He continues to conduct Politicking with Larry King, a weekly political talk show that has aired weekly on the same two channels since 2013. King's early life and education were born in Brooklyn, New York, one of two children of Jenny (Gitlitz), a sewing worker who was born in Vilnius, Lithuania, and Aaron Seiger, a restaurant owner and defense factory worker who was born in Kolomia, Austria-Hungary. -

'Talk Show Democracy'—On the Line with Larry King

The Father of "Talk Show Democracy" On the Line with Larry King N THE AFTERMATH of what surely was the most extraordinary presidential campaign ever for the American news I media, the Larry King story-like the man himself-has taken on almost mythic proportions: Horatio Alger Makes Good. Real good. Today, the mantle of media greatness rests easy on the self described "Jewish kid from Brooklyn" in the wake of events that defined the "top banana of talk show hosts" as the undisputed king maker of the 1990S. Consider: During the presidential race, Ross Perot announced his candidacy (twice) on "Larry King Live"; after belittling the idea, an uncomfortable (and, finally, desperate) George Bush came on the show late in a losing campaign; and Bill Clinton, mindful of King's role in his victory, promised to be back every six months ifhe won. Though self-effacing ("I'm just the interlocutor"), Larry King doesn't reject the label of Father of America's new "electronic democ racy," a revolution that came of age, he acknowledges, with Perot's coy, on-air concession on Feb. 20, 1992, that he'd run for president if drafted. With that show, Larry King became an instant oracle, rank ing second (after venerable sense-maker David Brinkley), Media Studies Center research found, among most frequently cited political pundits, while catching both grief from the traditional news media and loyalty of audiences and candidates. "1 don't get carried away with it," King told Journal Editor Edward Pease in an interview in King's CNN office in March. -

The Montgazette | May 2021

Help end Asian hate Chadwick Boseman The “Barrow Study” Enjoy local ramen, Page 7 An icon gone too soon, Page 16 A tribute to a student, Page 3 a student publication FREE Issue 86 Serving Montgomery County Community College and the Surrounding Community May 2021 Help end Asian hate Read on Page 7. Photo by Getty Images. Page 2 THE MONTGAZETTE May 2021 The Staff Josh Young Editor-in-Chief Michael Chiodo Sufyan Davis-Arrington Khushi Desai Sheridan Hamill Daniel Johnson Nina Lima Anthony Sannicandro Farewell and thank you Audrey Schippnick Emma Shainline Nicholas Young May Contributors Yaniv Aronson for the memories Robin Bonner Advisors Josh Young Joshua Woodroffe Design & Layout The Montgazette Editor-in-Chief Hello, once again, everyone. semester and helped me grow have had over the past couple of this paper, and the exploits of the I hope that you are all in a into my role as editor-in-chief years. During my time here, we people I have mentioned above position to succeed and thrive of The Montgazette. Without published very few issues with a would be for nothing, and The as we approach the end of the her, I am not sure that I would lack of articles. You guys always Montgazette would likely cease semester and finals week. I wish have had the confidence to made meetings a lot of fun and to exist. So, once again, thank everyone good luck and hope go for it and gain the valuable something that I looked forward you for reading and making all you have a restful summer break. -

William H. Parker and the Thin Blue Line: Politics, Public

WILLIAM H. PARKER AND THE THIN BLUE LINE: POLITICS, PUBLIC RELATIONS AND POLICING IN POSTWAR LOS ANGELES By Alisa Sarah Kramer Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of American University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy In History Chair: Michael Kazin, Kimberly Sims1 Dean o f the College of Arts and Sciences 3 ^ Date 2007 American University Washington, D.C. 20016 AMERICAN UNIVERSITY UBRARY Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. UMI Number: 3286654 Copyright 2007 by Kramer, Alisa Sarah All rights reserved. INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. ® UMI UMI Microform 3286654 Copyright 2008 by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest Information and Learning Company 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. © COPYRIGHT by Alisa Sarah Kramer 2007 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. I dedicate this dissertation in memory of my sister Debby. -

Food Assessment Report

Permit County Audit Date Facility Address Number Total Audits Count 5984 Abbeville Count 23 Abbeville 04/29/2020 01-206-00944 HARDEE'S # 1501697 110 W GREENWOOD STREET '-- Abbeville 04/29/2020 01-206-00934 IRENE'S OF DUE WEST 201 MAIN ST '-- Abbeville 05/13/2020 01-206-00973 CROSSROADS CONV STORE, LLC 758 HWY 28 BYPASS '-- Abbeville 05/18/2020 01-206-00798 MARIA'S MEXICAN RESTAURANT 125 COURT SQUARE '-- Abbeville 05/19/2020 01-204-00975 BROKEN ROAD BBQ MOBILE 1496 HOOK ROAD '-- Abbeville 05/19/2020 01-206-00974 BROKEN ROAD BBQ - BASE 1496 HOOK ROAD '-- Abbeville 05/22/2020 01-206-00908 NAP'S GROCERY & VARIETY #3 501 CAMBRIDGE ST '-- Abbeville 06/03/2020 01-206-00965 STOP A MINIT 700 W GREENWOOD ST '-- Abbeville 06/08/2020 01-206-00973 CROSSROADS CONV STORE, LLC 758 HWY 28 BYPASS '-- Abbeville 06/10/2020 01-206-00973 CROSSROADS CONV STORE, LLC 758 HWY 28 BYPASS '-- Abbeville 06/12/2020 01-206-00961 OLD COUNTRY DINER 91 HWY 72 W '-- Abbeville 06/18/2020 01-206-00972 DAILY BREAD BAKERY LLC 109 WASHINGTON ST '-- Abbeville 06/19/2020 01-206-00943 ROUGH HOUSE 116 COURT SQUARE '-- Abbeville 06/22/2020 01-206-00954 SAVANNAH GRILL 101 N COX AVE '-- Abbeville 06/23/2020 01-206-00738 COLD SPRINGS STORE 1151 HWY 20 '-- Abbeville 06/24/2020 01-206-00838 SAXON'S HOT DOGS 381 HIGHWAY 72 W '-- Abbeville 06/24/2020 01-206-00877 THEO'S 302-1 S MAIN ST '-- Abbeville 06/24/2020 01-206-00872 MAIN ST COFFEE CO 109 S MAIN ST '-- Abbeville 06/25/2020 01-206-00945 HUDSON'S CAFE 113 S CALHOUN SHORES PKWY '-- Abbeville 06/25/2020 01-206-00899 FOOD FOR THE SOUL -

Opinion/Editorial

Page 2, The Gladewater Mirror, Wednesday, Jan. 30, 2019 OPINION/EDITORIAL We have a mission… For a little old country girl from the Blackland Prairie I have had Suzanne THE ECONOMIST the opportunity to meet a lot, and I mean a lot, of famous people. By Dr. M. Ray Perryman Most of the time it was because I am not shy and because I am mar- ried to a lifelong journalist who has often been on an ‘A’ list that Bardwell Data blessed us with opportunity. The partial shutdown of the federal government continues. (While Now you may not feel that my celebrity list is all that impressive, it would be good news indeed if it’s reopened by the time you’re read- but I hug the memories with glee and am just too giddy from the ing this, as I am writing both sides are digging in their heels and hardly latest opportunity not to share it with you, my friends and neighbors. listening to each other, so it may well persist.) First let’s see if I can remember just some of the folks old Jimmy Headlines are replete with the fallout from some 800,000 federal Bardwell has positioned me to meet: rock star Peter Frampton (an- employees either staying home or being forced to work without pay. niversary gift), ‘70s pop star B.J. Thomas (he’s my distant cousin), The financial hardships for these individu- astronauts Alan Shepard, Gordon Cooper, Scott Carpenter and Wally als and families are mounting, and many are Schirra. (Wally even winked at me! For a baby boomer who grew up struggling to find alternative ways to make on the space race that was the thrill of a lifetime.) I also met the first some interim cash.