Swiss Guidelines on Management of Dying and Death

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What Does the COVID-19 Pandemic Mean for HIV, Tuberculosis, and Malaria Control? Floriano Amimo1,2* , Ben Lambert3 and Anthony Magit4

Amimo et al. Tropical Medicine and Health (2020) 48:32 Tropical Medicine https://doi.org/10.1186/s41182-020-00219-6 and Health SHORT REPORT Open Access What does the COVID-19 pandemic mean for HIV, tuberculosis, and malaria control? Floriano Amimo1,2* , Ben Lambert3 and Anthony Magit4 Abstract Despite its current relatively low global share of cases and deaths in Africa compared to other regions, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has the potential to trigger other larger crises in the region. This is due to the vulnerability of health and economic systems, coupled with the high burden of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), tuberculosis (TB), and malaria. Here we examine the potential implications of COVID-19 on the control of these major epidemic diseases in Africa. We use current evidence on disease burden of HIV, TB, and malaria, and epidemic dynamics of COVID-19 in Africa, retrieved from the literature. Our analysis shows that the current measures to control COVID-19 neglect important and complex context-specific epidemiological, social, and economic realities in Africa. There is a similarity of clinical features of TB and malaria, with those used to track COVID-19 cases. This coupled with institutional mistrust and misinformation might result in many patients with clinical features similar to those of COVID-19 being hesitant to voluntarily seek care in a formal health facility. Furthermore, most people in productive age in Africa work in the informal sector, and most of those in the formal sector are underemployed. With the current measures to control COVID-19, these populations might face unprecedented difficulties to access essential services, mainly due to reduced ability of patients to support direct and indirect medical costs, and unavailability of transportation means to reach health facilities. -

GAO-11-599 Child Maltreatment: Strengthening National Data on Child Fatalities Could Aid in Prevention

United States Government Accountability Office Report to the Chairman, Committee on GAO Ways and Means, House of Representatives July 2011 CHILD MALTREATMENT Strengthening National Data on Child Fatalities Could Aid in Prevention GAO-11-599 July 2011 CHILD MALTREATMENT Strengthening National Data on Child Fatalities Could Aid in Prevention Highlights of GAO-11-599, a report to the Chairman, Committee on Ways and Means, House of Representatives Why GAO Did This Study What GAO Found Children’s deaths from maltreatment More children have likely died from maltreatment than are counted in NCANDS, are especially distressing because they and HHS does not take full advantage of available information on the involve a failure on the part of adults circumstances surrounding child maltreatment deaths. NCANDS estimated that who were responsible for protecting 1,770 children in the United States died from maltreatment in fiscal year 2009. them. Questions have been raised as According to GAO’s survey, nearly half of states included data only from child to whether the federal National Child welfare agencies in reporting child maltreatment fatalities to NCANDS, yet not all Abuse and Neglect Data System children who die from maltreatment have had contact with these agencies, (NCANDS), which is based on possibly leading to incomplete counts. HHS also collects but does not report voluntary state reports to the some information on the circumstances surrounding child maltreatment fatalities Department of Health and Human that could be useful for prevention, such as perpetrators’ previous maltreatment Services (HHS), fully captures the number or circumstances of child of children. The National Center for Child Death Review (NCCDR), a fatalities from maltreatment. -

Years of Life Lost of Inhabitants of Rural Areas in Poland Due to Premature Mortality Caused by External Reasons of Death 1999–2012

Annals of Agricultural and Environmental Medicine 2016, Vol 23, No 4, 598–603 www.aaem.pl ORIGINAL ARTICLE Years of life lost of inhabitants of rural areas in Poland due to premature mortality caused by external reasons of death 1999–2012 Marek Bryła1, Irena Maniecka-Bryła2, Monika Burzyńska2, Małgorzata Pikala2 1 Department of Social Medicine, Chair of Social and Preventive Medicine, Medical University, Lodz, Poland 2 Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Chair of Social and Preventive Medicine, Medical University, Lodz, Poland Bryła M, Maniecka-Bryła I, Burzyńska M, Pikala M. Years of life lost of inhabitants of rural areas in Poland due to premature mortality caused by external reasons of death 1999–2012. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2016; 23(4): 598–603. doi: 10.5604/12321966.1226853 Abstract Introduction. External causes of death are the third most common causes of death, after cardiovascular diseases and malignant neoplasms, in inhabitants of Poland. External causes of death pose the greatest threat to people aged 5–44, which results in a great number of years of life lost. Objective. The aim of the study is the analysis of years of life lost due to external causes of death among rural inhabitants in Poland, particularly due to traffic accidents and suicides. Material and methods. The study material included a database created on the basis of 2,100,785 certificates of rural inhabitants in Poland in the period 1999–2012. The SEYLLp (Standard Expected Years of Life Lost per living person) and the SEYLLd (per death) indices were used to determine years of life lost due to external causes of death. -

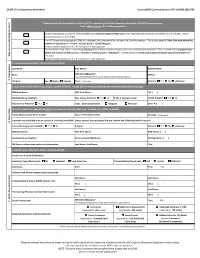

OCME Clinical Summary Worksheet Fax to OCME Communications 24/7 at (646) 500-5762 Please Be Advised That Failure to Notify Next

OCME Clinical Summary Worksheet Fax to OCME Communications 24/7 at (646) 500-5762 Please indicate why the health care facility (HCF) is submitting the Clinical Summary Worksheet to OCME Communications. Please check only one of the following options: OCME has accepted jurisdiction of this decedent as a Medical Examiner (ME) case or has requested the physician submit this form for review. Please complete sections A, B, C, D & E The HCF is requesting storage at OCME of a decedent until the next-of-kin are ready to claim the remains. This is considered a Claim Only case where the method of disposition is "interim" and the place is "OCME Morgue". Please complete sections A, B, C & D (section E is not required) The decedent's next-of-kin is requesting City Burial for a decedent whose death is due exclusively to natural disease. This is considered a City Burial case where the method of disposition is "interment" and the place is "City Burial". Please submit the letter authorizing City Burial signed by the NOK with Why are submitting you Why this form? this form. Please complete sections A, B, C & D (section E is not required) A. Decedent Demographics: please complete all fields Last Name: First Name: Middle Name: Alias: DOB (mm/dd/yyyy)*: MRN #: *For intrauterine fetal demise (IUFD), please provide the date of delivery A. DemographicsA. Religion: Sex: Male / Female Race: Veteran: Y / N / Unknown B. Next-of-Kin (NOK) Information: please complete all fields. PLEASE NOTIFY OCME AS UPDATED INFORMATION BECOMES AVAILABLE NOK Last Name: NOK First Name: Tel: ( ) - Relationship to decedent: Was Family Notified? Y / N If No, # attempts made: Family Present? Y / N Objection to Autopsy? Y / N If yes, why? (Check One): Religious Personal Other #: ( ) - The below additional information MUST be provided for all Claim Only cases in which next-of-kin is unknown. -

A Reconsideration of Identity Through Death and Bereavement and Consequent Pastoral Implications for Christian Ministry

A Reconsideration of Identity through Death and Bereavement and consequent Pastoral implications for Christian Ministry by The Rev. Christopher Race for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The study considers the idea that bio-death has teleological meaning within the evolution of Personhood of relational identity in resurrection; and the results of pastoral ministry pro-actively engaging with dying as a pilgrimage into and through bio-death, in which every member of the immediate community of faith is pro-active. Department of Philosophy, Theology and Religion College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham January, 2012 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. INFORMATION FOR ABSTRACTING AND INDEXING SERVICES The information on this form will be published. To minimize any risk of inaccuracy, please type your text. Please supply two copies of this abstract page. Full name (surname first): RACE, CHRISTOPHER KEITH School/Department: SCHOOL OF PHILOSOPHY, THEOLOGY AND RELIGION/DEPARTMENT OF THEOLOGY AND RELIGION Full title of thesis/dissertation: A RECONSIDERATION OF IDENTITY THROUGH DEATH AND BEREAVEMENT AND CONSEQUENT PASTORAL IMPLICATIONS FOR CHRISTIAN MINISTRY Degree: PhD Date of submission: 31.01.2012 Date of award of degree (leave blank): Abstract (not to exceed 200 words - any continuation sheets must contain the author's full name and full title of the thesis/dissertation): This work seeks to examine traditional Christian doctrines regarding life after death, from a pastoral perspective. -

What Does the COVID-19 Pandemic Mean for HIV, Tuberculosis, and Malaria Control? Floriano Amimo1,2* , Ben Lambert3 and Anthony Magit4

Amimo et al. Tropical Medicine and Health (2020) 48:32 Tropical Medicine https://doi.org/10.1186/s41182-020-00219-6 and Health SHORT REPORT Open Access What does the COVID-19 pandemic mean for HIV, tuberculosis, and malaria control? Floriano Amimo1,2* , Ben Lambert3 and Anthony Magit4 Abstract Despite its current relatively low global share of cases and deaths in Africa compared to other regions, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has the potential to trigger other larger crises in the region. This is due to the vulnerability of health and economic systems, coupled with the high burden of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), tuberculosis (TB), and malaria. Here we examine the potential implications of COVID-19 on the control of these major epidemic diseases in Africa. We use current evidence on disease burden of HIV, TB, and malaria, and epidemic dynamics of COVID-19 in Africa, retrieved from the literature. Our analysis shows that the current measures to control COVID-19 neglect important and complex context-specific epidemiological, social, and economic realities in Africa. There is a similarity of clinical features of TB and malaria, with those used to track COVID-19 cases. This coupled with institutional mistrust and misinformation might result in many patients with clinical features similar to those of COVID-19 being hesitant to voluntarily seek care in a formal health facility. Furthermore, most people in productive age in Africa work in the informal sector, and most of those in the formal sector are underemployed. With the current measures to control COVID-19, these populations might face unprecedented difficulties to access essential services, mainly due to reduced ability of patients to support direct and indirect medical costs, and unavailability of transportation means to reach health facilities. -

Fatal Accidents at Work in Agriculture Associated with Alcohol Intoxication in Lower Silesia in Poland

Medycyna Pracy 2017;68(1):23–30 http://medpr.imp.lodz.pl/en https://doi.org/10.13075/mp.5893.00430 ORIGINAL PAPER Tomasz Jurek1 Marta Rorat2 Fatal accidents at work IN agriculture ASSOCIATED WITH ALCOHOL INTOXICATION IN LOWER SILESIA IN POLAND ŚMIERTELNE WYPADKI PRZY PRACY W ROLNICTWIE NA DOLNYM ŚLĄSKU W POLSCE ZWIĄZANE Z UPOJENIEM ALKOHOLOWYM Wroclaw Medical University / Uniwersytet Medyczny we Wrocławiu, Wrocław, Poland Faculty of Medicine, Department of Forensic Medicine / Wydział Lekarski, Katedra Medycyny Sądowej 1 Zakład Medycyny Sądowej / Forensic Medicine Unit 2 Zakład Prawa Medycznego / Medical Law Unit Abstract Background: Determining the prevalence of alcohol intoxication and the level of intoxication in victims of fatal occupational accidents is necessary to improve work safety. The circumstances of the accident and the time between alcohol consumption and death are important factors. Material and Methods: A retrospective review of 18 935 medico-legal autopsy reports and toxicological reports performed in the Department of Forensic Medicine at the Wroclaw Medical University, Poland, in the years 1991–2014. The study protocol included circumstances, time and cause of death, injuries, quantitative testing for the presence of ethyl alcohol, gender and age. Results: There were 98 farm-related fatalities. There were 41.8% (N = 41) of victims who had been intoxicated – 95.1% (N = 39) of them were males aged 19–70 years old, 4.9% (N = 2) were females aged 37–65 years old. In 8 cases the blood alcohol concentration (BAC) was 50–150 mg/dl; in 15 cases it was 150–250 mg/dl and in 18 cases it was > 250 mg/dl. -

Profile of Alleged Suicidal Deaths Autopsied at Belgaum Institute of Medical Sciences, Belagavi

Original Research Article Profile of alleged suicidal deaths autopsied at Belgaum institute of medical sciences, Belagavi Hari Prasad V1, Shruti N Malagar2*, Ashok Kumar Shetty3 1Assistant Professor, Department of Forensic Medicine, MVJ Medical College and Research Hospital, Hoskote, Bangalore- 562114 2Post Graduate ,3Professor& HOD, Department of Forensic Medicine, Belgaum Institute of Medical Sciences, Belagavi – 590001, INDIA. Email: [email protected] Abstract Background: The present cross-sectional study was conducted at a tertiary care center, Belgaum for a period of 13 months from December 2013 to December 2014. The aim of this study was to know the pattern of suicides with respect to age, sex, domicile pattern and method adopted for suicide. A total of 842 autopsies were conducted during the study period of which 182 cases were of alleged suicidal deaths amounting for 21.61% of the mortality burden of all the medico legal autopsies done in our study area, Belagavi. Key words: Autopsy, mortality, pattern, suicide. *Address for Correspondence: Dr Shruti N Malagar, Post Graduate, Department of Forensic Medicine, Belgaum Institute of Medical Sciences, Belagavi – 590001, INDIA. Email: [email protected] Received Date: 20/11/2019 Revised Date: 26/12/2019 Accepted Date: 06/02/2020 DOI: https://doi.org/10.26611/10181411 and suicide attempts is required for effective suicide Access this article online prevention strategies. Quick Response Code: Website: MATERIALS AND METHODS www.medpulse.in A cross sectional study from December 2013 to December 2014 was carried out at Belgaum Institute of Medical Sciences, Belagavi. Information about the victims of Accessed Date: alleged suicide brought for autopsy, were obtained from hospital case records, police records and by direct 16 April 2020 interrogation with the, next of kin, friends and other relatives accompanying the victims. -

Stratigraphy, Morphology, and Paleoecology of a Fossil Peccary Herd from Western Kentucky

Stratigraphy, Morphology, and Paleoecology of a Fossil Peccary Herd From Western Kentucky By WARREN I. FINCH, FRANK C. WHITMORE, JR., and JOHN D. SIMS GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 790 W ark done in part in cooperation with the Kentucky Geological Survey Nature of the death and burial of the herd and comparison with other fossil peccary herds of North America UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1972 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR ROGERS C. B. MORTON, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY V. E. McKelvey, Director Library of Congress catalog-card No. 72-600269 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402- Price 70 cents (paper cover) Stock Number 2401-00248 CONTENTS Page Page Abstract..................................................................................... 1 Fossils-Continued Introduction.............................................................................. 1 Platygonus compressus Le Conte 1848-Continued Acknowledgments .............. .'...................................................... 1 Composition and inferred habits of the herd...... 17 Geologic setting........................................................................ 2 Other herds of Platygonus compressus................ 18 Silt stratigraphy...................................................................... 2 Denver, Colo., herd........................................... 18 Silt petrology............................................................................ 4 Goodland, -

United States Department of the Interior

United States Department of the Interior FISH AND WILDLIFE SERVICE Roseburg Field Office 2900 NW Stewart Parkway Roseburg, Oregon 97471 Phone: (541) 957-3474 FAX: (541)957-3475 In Reply Refer To: OIEOFW00-2014-F-0161 June 25, 2014 Filename: Douglas Complex Post Fire Salvage BiOp Tails#: 01 EOFW00-2014-F-0!6! TS#: 14-576 Memorandum To: District Manager, Medford District Bureau of Land Management Medford, Oregon ~~ -r;t~i!J *1 From: Field Supervisor, Roseburg Fish and Wildlife Office Roseburg, Oregon Subject: Formal consultation on the Medford Douglas Post-Fire Salvage Project (Reference Number 0 1EOFW00-20 14-F-0 161) Tllis document transmits the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service's (Service) Biological Opinion (Opinion) addressing the Medford Douglas Post-Fire Salvage Project proposed by the Medford District (District) of the Bureau of Land Management (BLM). At issue are the effects of the proposed action (or Project) on the threatened northern spotted owl (Strix occidentqlis caw·ina) (spotted owl) and spotted owl critical habitat. The attached Opinion was prepared in accordance with the requirements of section 7 of the Endangered Species Act (ESA) of 1973 as amended (16U.S.C. 1531 et seq.). The Opinion is based on information provided in the District's Biological Assessment (USDI BLM 2014; Assessment), dated April28, 2014 and received in our office on April 30, 2014, along with other sources of information cited herein. A complete decision record for this consultation is on file at the Service' s Roseburg Field Office. The Opinion includes a finding by the Service that the District's proposed action is not likely to jeopardize the spotted owl or adversely modify spotted owl critical habitat. -

NECK POSTURE, DENTITION, and FEEDING STRATEGIES in JURASSIC SAUROPOD DINOSAURS KENT A. STEVENS and J. MICHAEL PARRISH Departmen

NECK POSTURE, DENTITION, AND FEEDING STRATEGIES IN JURASSIC SAUROPOD DINOSAURS KENT A. STEVENS and J. MICHAEL PARRISH Department of Computer and Information Science University of Oregon, Eugene, OR 97403; Department of Biological Sciences Northern Illinois University, DeKalb, IL 60115 Stevens: (541) 346-4430 (office) (541) 346-5373 (fax) [email protected] 2 INTRODUCTION Sauropod dinosaurs represent the extremes of both gigantism and neck elongation in the history of terrestrial vertebrates. Neck lengths were extreme in both absolute and relative measure. The necks of the Jurassic sauropods Barosaurus and Brachiosaurus were about 9m long, well over twice the length of their dorsal columns. Even the relatively short-necked Camarasaurus, with a cervical column about 3.5 m long, had a neck substantially longer than its trunk. Because of their elongate necks, massive bulk, abundance, and diversity, the feeding habits of the sauropod dinosaurs of the Jurassic period has been a subject of inquiry and dispute since relatively complete fossils of this clade were first discovered over 100 years ago. Analysis of the functional morphology and paleoecology of sauropods has led to a diversity of interpretations of their feeding habits. Sauropods have been interpreted as high browsers, low browsers, aquatic, terrestrial, bipedal, tripodal, and have even been restored with elephant-style probosces. Furthermore, differences in neck length, body shape, cranial anatomy, and dental morphology. Here we will review various lines of evidence relating to feeding in sauropods and reconsider them in light of our own studies on neck pose, mobility, and inferred feeding envelopes in Jurassic sauropods. Sauropods varied considerably in body plan and size, resulting in a range of head heights across the different taxa, when feeding in a neutral, quadrupedal stance. -

Dying in Full Detail: Mortality and Digital Documentary

DYING IN FULL DETAIL This page intentionally left blank DYING IN FULL DETAIL mortality and digital documentary Jennifer Malkowski Duke University Press • Durham and London • 2017 © 2017 duke university press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper ∞ Text designed by Courtney Leigh Baker Typeset in Whitman and Futura by Graphic Composition, Inc., Bogart, GA Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Malkowski, Jennifer, [date]– author. Title: Dying in full detail : mortality and digital documentary / Jennifer Malkowski. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2017. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: lccn 2016034893 isbn 9780822363002 (hardcover : alk. paper) isbn 9780822363156 (pbk. : alk. paper) isbn 9780822373414 (ebook) Subjects: lcsh: Documentary films—Production and direction—Moral and ethical aspects. | Documentary mass media. | Death in motion pictures. | Digital cinematography—Technique. Classification: lcc pn1995.9.d6 m33 2017 | ddc 070.1/ 8—dc23 lc record available at https:// lccn.loc .gov/ 2016034893 Cover art: ap Photo/Richard Drew FOR JOY, my grandmother, who died a good death This page intentionally left blank contents Acknowledgments • ix Introduction • 1 1 3 CAPTURING THE “MOMENT” “A NEGATIVE PLEASURE” photography, film, and suicide’s digital death’s elusive duration sublimity 23 109 2 4 THE ART OF DYING, ON VIDEO STREAMING DEATH deathbed the politics of dying documentaries on youtube 67 155 Conclusion The Nearest Cameras Can Go • 201 Notes • 207 Bibliography • 231 Index • 241 This page intentionally left blank acknowledgments Many people have supported me through my writing of this project, starting in its infancy at Oberlin College, where Geoff Pingree and Pat Day supervised my honors thesis on death in documentary film and gave me the confidence to pursue an academic career.