Judicial Branch

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Iron County Heads to Polls Today

Mostly cloudy High: 49 | Low: 32 | Details, page 2 DAILY GLOBE yourdailyglobe.com Tuesday, April 4, 2017 75 cents Iron County TURKEY STRUT heads to polls today By RICHARD JENKINS sor, three candidates — incum- [email protected] bent Jeff Stenberg, Tom Thomp- HURLEY — Iron County vot- son Jr. and James Schmidt — ers head to the polls today in a will be vying for two town super- series of state and local races. visor seats. Mercer Clerk Chris- At the state level, voters will tan Brandt and Treasurer Lin decide between incumbent Tony Miller are running unopposed. Evers and Lowell Holtz to see There is also a seat open on who will be the state’s next the Mercer Sanitary Board, how- superintendent of public instruc- ever no one has filed papers to tion. Annette Ziegler is running appear on the ballot. unopposed for another term as a The city of Montreal also has justice on the Wisconsin two seats up for election. In Supreme Court. Ward 1, Joan Levra is running Iron County Circuit Court unopposed to replace Brian Liv- Judge Patrick Madden is also ingston on the council, while running unopposed for another Leola Maslanka is being chal- term on the bench. lenged by Bill Stutz for her seat Iron County’s local municipal- representing Ward 2. ities also have races on the ballot The other town races, all of — including contested races in which feature unopposed candi- Kimball, Mercer and Montreal. dates, are as follows: In Kimball, Town Chairman —Anderson: Edward Brandis Ron Ahonen is being challenged is running for chairman, while by Joe Simonich. -

2019 Guide to the Wisconsin Supreme Court and Judicial Evaluation Fourth Edition: 2018-19 Term

2019 Guide to the Wisconsin Supreme Court and Judicial Evaluation Fourth Edition: 2018-19 Term November 2019 2019 GUIDE TO THE WISCONSIN SUPREME COURT AND JUDICIAL EVALUATION Prepared By: Paige Scobee, Hamilton Consulting Group, LLC November 2019 The Wisconsin Civil Justice Council, Inc. (WCJC) was formed in 2009 to represent Wisconsin business inter- ests on civil litigation issues before the legislature and courts. WCJC’s mission is to promote fairness and equi- ty in Wisconsin’s civil justice system, with the ultimate goal of making Wisconsin a better place to work and live. The WCJC board is proud to present its fourth Guide to the Wisconsin Supreme Court and Judicial Evalua- tion. The purpose of this publication is to educate WCJC’s board members and the public about the role of the Supreme Court in Wisconsin’s business climate by providing a summary of the most important decisions is- sued by the Wisconsin Supreme Court affecting the Wisconsin business community. Board Members Bill G. Smith Jason Culotta Neal Kedzie National Federation of Independent Midwest Food Products Wisconsin Motor Carriers Business, Wisconsin Chapter Association Association Scott Manley William Sepic Matthew Hauser Wisconsin Manufacturers & Wisconsin Automobile & Truck Wisconsin Petroleum Marketers & Commerce Dealers Association Convenience Store Association Andrew Franken John Holevoet Kristine Hillmer Wisconsin Insurance Alliance Wisconsin Dairy Business Wisconsin Restaurant Association Association Brad Boycks Wisconsin Builders Association Brian Doudna Wisconsin Economic Development John Mielke Association Associated Builders & Contractors Eric Borgerding Gary Manke Wisconsin Hospital Association Midwest Equipment Dealers Association 10 East Doty Street · Suite 500 · Madison, WI 53703 www.wisciviljusticecouncil.org · 608-258-9506 WCJC 2019 Guide to the Wisconsin Supreme Court Page 2 and Judicial Evaluation Executive Summary The Wisconsin Supreme Court issues decisions that have a direct effect on Wisconsin businesses and individu- als. -

2015-2016 Wisconsin Blue Book: Chapter 7

Judicial 7 Branch The judicial branch: profile of the judicial branch, summary of recent significant supreme court decisions, and descriptions of the supreme court, court system, and judicial service agencies Cassius Fairchild (Wisconsin Veterans Museum) 558 WISCONSIN BLUE BOOK 2015 – 2016 WISCONSIN SUPREME COURT Current Term First Assumed Began First Expires Justice Office Elected Term July 31 Shirley S. Abrahamson. 1976* August 1979 2019 Ann Walsh Bradley . 1995 August 1995 2015** N. Patrick Crooks . 1996 August 1996 2016 David T. Prosser, Jr. �������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 1998* August 2001 2021 Patience Drake Roggensack, Chief Justice . 2003 August 2003 2023 Annette K. Ziegler . 2007 August 2007 2017 Michael J. Gableman . 2008 August 2008 2018 *Initially appointed by the governor. **Justice Bradley was reelected to a new term beginning August 1, 2015, and expiring July 31, 2025. Seated, from left to right are Justice Annette K. Ziegler, Justice N. Patrick Crooks, Justice Shirley S. Abrahamson, Chief Justice Patience D. Roggensack, Justice Ann Walsh Bradley, Justice David T. Prosser, Jr., and Justice Michael J. Gableman. (Wisconsin Supreme Court) 559 JUDICIAL BRANCH A PROFILE OF THE JUDICIAL BRANCH Introducing the Court System. The judicial branch and its system of various courts may ap- pear very complex to the nonlawyer. It is well-known that the courts are required to try persons accused of violating criminal law and that conviction in the trial court may result in punishment by fine or imprisonment or both. The courts also decide civil matters between private citizens, ranging from landlord-tenant disputes to adjudication of corporate liability involving many mil- lions of dollars and months of costly litigation. -

National Association of Women Judges Counterbalance Spring 2012 Volume 31 Issue 3

national association of women judges counterbalance Spring 2012 Volume 31 Issue 3 INSIDE THIS ISSUE Poverty’s Impact on the Administration of Justice / 1 President’s Message / 2 Executive Director’s Message / 3 Cambridge 2012 Midyear Meeting and Leadership Conference / 6 MEET ME IN MIAMI: NAWJ 2012 Annual Conference / 8 District News / 10 Immigration Programs News / 20 Membership Moments / 20 Women in Prison Report / 21 Louisiana Women in Prison / 21 Maryland Women in Prison / 23 NAWJ District 14 Director Judge Diana Becton and Contra Costa County native Christopher Darden with local high school youth New York Women in Prison / 24 participants in their November, 2011 Color of Justice program. Read more on their program in District 14 News. Learn about Color of Justice in creator Judge Brenda Loftin’s account on page 33. Educating the Courts and Others About Sexual Violence in Unexpected Areas / 28 NAWJ Judicial Selection Committee Supports Gender Equity in Selection of Judges / 29 POVERTY’S IMPACT ON THE ADMINISTRATION Newark Conference Perspective / 30 OF JUSTICE 1 Ten Years of the Color of Justice / 33 By the Honorable Anna Blackburne-Rigsby and Ashley Thomas Jeffrey Groton Remembered / 34 “The opposite of poverty is justice.”2 These words have stayed with me since I first heard them Program Spotlight: MentorJet / 35 during journalist Bill Moyers’ interview with civil rights attorney Bryan Stevenson. In observance News from the ABA: Addressing Language of the anniversary of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s assassination, they were discussing what Dr. Access / 38 King would think of the United States today in the fight against inequality and injustice. -

How Do Judges Decide School Finance Cases?

HOW DO JUDGES DETERMINE EDUCATIONAL RIGHTS? Ethan Hutt,* Daniel Klasik,† & Aaron Tang‡ ABSTRACT There is an old riddle that asks, what do constitutional school funding lawsuits and birds have in common? The answer: every state has its own. Yet while almost every state has experienced hotly-contested school funding litigation, the results of these suits have been nearly impossible to predict. Scholars and advocates have struggled for decades to explain why some state courts rule for plaintiff school children—often resulting in billions of dollars in additional school spending—while others do not. If there is rough agreement on anything, it is that “the law” is not the answer: variation in the strength of state constitutional education clauses is uncorrelated with the odds of plaintiff success. Just what factors do explain different outcomes, though, is anybody’s guess. One researcher captured the academy’s state of frustration aptly when she suggested that whether a state’s school funding system will be invalidated “depends almost solely on the whimsy of the state supreme court justices themselves.” In this Article, we analyze an original data set of 313 state-level school funding decisions using multiple regression models. Our findings confirm that the relative strength of a state’s constitutional text regarding education has no bearing on school funding lawsuit outcomes. But we also reject the judicial whimsy hypothesis. Several variables— including the health of the national economy (as measured by GDP growth), Republican control over the state legislature, and an appointment-based mechanism of judicial selection—are significantly and positively correlated with the odds of a school funding system being declared unconstitutional. -

Famous Cases of the Wisconsin Supreme Court

In Re: Booth 3 Wis. 1 (1854) What has become known as the Booth case is actually a series of decisions from the Wisconsin Supreme Court beginning in 1854 and one from the U.S. Supreme Court, Ableman v. Booth, 62 U.S. 514 (1859), leading to a final published decision by the Wisconsin Supreme Court in Ableman v. Booth, 11 Wis. 501 (1859). These decisions reflect Wisconsin’s attempted nullification of the federal fugitive slave law, the expansion of the state’s rights movement and Wisconsin’s defiance of federal judicial authority. The Wisconsin Supreme Court in Booth unanimously declared the Fugitive Slave Act (which required northern states to return runaway slaves to their masters) unconstitutional. The U.S. Supreme Court overturned that decision but the Wisconsin Supreme Court refused to file the U.S. Court’s mandate upholding the fugitive slave law. That mandate has never been filed. When the U.S. Constitution was drafted, slavery existed in this country. Article IV, Section 2 provided as follows: No person held to service or labor in one state under the laws thereof, escaping into another, shall in consequence of any law or regulation therein, be discharged from such service or labor, but shall be delivered up on claim of the party to whom such service or labor may be due. Based on this provision, Congress in 1793 passed a law that permitted the owner of any runaway slave to arrest him, take him before a judge of either the federal or state courts and prove by oral testimony or by affidavit that the person arrested owed service to the claimant under the laws of the state from which he had escaped; if the judge found the evidence to be sufficient, the slave owner could bring the fugitive back to the state from which he had escaped. -

Marquette Lawyer Spring 2009 Marquette University Law Alumni Magazine

Marquette Lawyer Spring 2009 Marquette University Law Alumni Magazine Marquette Lawyers On the Front Lines of Justice Also Inside: Doyle, Lubar, McChrystal, O’Scannlain, Rofes, Sykes, Twerski Marquette University Rev. Robert A. Wild, S.J. TABLE OF CONTENTS President John J. Pauly Provost 3 From the Dean Gregory J. Kliebhan Senior Vice President 4 Marquette Lawyers On the Front Lines of Justice Marquette University Law School 1 2 A Conversation with Mike McChrystal on Eckstein Hall Joseph D. Kearney Dean and Professor of Law [email protected] 1 8 2008 Commencement Ceremonies (414) 288-1955 Peter K. Rofes 2 2 Law School News Associate Dean for Academic Affairs and Professor of Law 2 6 Public Service Report Michael M. O’Hear Associate Dean for Research and Professor of Law 3 7 Alumni Association: President’s Letter and Annual Awards Bonnie M. Thomson Associate Dean for Administration 4 1 Alumni Class Notes and Profiles Jane Eddy Casper Assistant Dean for Students 5 5 McKay Award Remarks: Prof. Aaron D. Twerski Daniel A. Idzikowski Robert C. McKay Law Professor Award Assistant Dean for Public Service Paul D. Katzman 5 8 Rotary Club Remarks: Sheldon B. Lubar Assistant Dean for Career Planning Devolution of Milwaukee County Government Sean Reilly Assistant Dean for Admissions 6 4 Bar Association Speech: Hon. Diane S. Sykes Christine Wilczynski-Vogel The State of Judicial Selection in Wisconsin Assistant Dean for External Relations [email protected] 7 4 Hallows Lecture: Hon. Diarmuid F. O’Scannlain Marquette Lawyer is published by Lawmaking and Interpretation: The Role of a Federal Marquette University Law School. -

2010 April Montana Lawyer

April 2010 THE MONTANA Volume 35, No. 6 awyerTHE STATE BAR OF MONTANA SpecialL issue on Montana courts Tweeting Supreme Court docket is now a major viewable to all on the web trial Developments in the 2 biggest UM’s discipline cases student The trouble Grace Case with money in Project changes judicial elections the landscape for media coverage Chopping down the backlog Changes in procedures at the Supreme Court cuts the deficit Ethics opinion on the new in the caseload notary rule THE MONTANA LAWYER APRIL INDEX Published every month except January and July by the State Bar of Montana, 7 W. Sixth Ave., Suite 2B, P.O. Box 577, Helena MT 59624. Phone (406) 442-7660; Fax (406) 442-7763. Cover Story E-mail: [email protected] UM’s Grace Case Project: trial coverage via Internet 6 STATE BAR OFFICERS President Cynthia K. Smith, Missoula President-Elect Features Joseph Sullivan, Great Falls Secretary-Treasurer Ethics Opinion: notary-rule compliance 12 K. Paul Stahl, Helena Immediate Past President Money floods campaigns for judgeships 22 Chris Tweeten, Helena Chair of the Board Shane Vannatta, Missoula Commentary Board of Trustees Pam Bailey, Billings President’s Message: Unsung heroes 4 Pamela Bucy, Helena Darcy Crum, Great Falls Op-Ed: A nation of do-it-yourself lawyers 25 Vicki W. Dunaway, Billings Jason Holden, Great Falls Thomas Keegan, Helena Jane Mersen, Bozeman State Bar News Olivia Norlin, Glendive Mark D. Parker, Billings Ryan Rusche, Wolf Point Lawyers needed to aid military personnel 14 Ann Shea, Butte Randall Snyder, Bigfork Local attorneys and Law Day events 15 Bruce Spencer, Helena Matthew Thiel, Missoula State Bar Calendar 15 Shane Vannatta, Missoula Lynda White, Bozeman Tammy Wyatt-Shaw, Missoula Courts ABA Delegate Damon L. -

Notes on Alums Jack Auhk ('581 Was Elected to the Bench Atlanta Firm of Hurt, Richardson, Garner, in Branch 4 of the Dane County, Wis., Todd & Cadenhead

15 Notes on Alums Jack AuHk ('581 was elected to the bench Atlanta firm of Hurt, Richardson, Garner, in Branch 4 of the Dane County, Wis., Todd & Cadenhead. Mr. Thrcott recently Circuit Court in April, and assumed his completed a tour of duty with the US new position in August. Aulik has prac- Marine Corps. ticed law and lived in Sun Prairie Paul ], Fisher ('60) has been since 1959. appointed General Counsel for Ariston Steven W. Weinke ('661was recently Capital Management and California elected Circuit Court Judge for Fond du Divisional Manager. Lac County, Wis. Weinke succeeds US District Judge John Reynolds Eugene F. McEssey ('491, who served the ('491, a member of the Law School's county for 24 years. Board of Visitors, has announced that he Pat Richter ('71) has been named will take senior status in the Eastern Dis- director of personnel for Oscar Mayer trict of Wisconsin. Judge Reynolds had Foods Corp., Madison. Richter was per- also served as Wisconsin Attorney sonnel manager for the beverages divi- General and Governor. sion of General Foods, White Plains, N.Y. David W. Wood ('81) has joined the Alan R. Post ('72) has become an Columbus, Ohio firm of Vorys, Sater, associate with the firm Sorling, Northrup, Seymour and Pease. Hanna, Cullen and Cochran, Ltd., Spring- Scott Jennings ('75) has been named field, Ill. Post had been with Illinois Bell, an Associate Editor of the Lawyers Coop- Chicago. erative Publishing Co., Rochester, NY. James H. Haberstroh ('751 became a For the past seven years, Mr. Jennings vice president of First Wisconsin Trust was with the US Department of Energy Co., Milwaukee. -

Fall 2010 a Crossroads for Discussion of Public Policy—This Is an Important Emerging Initiative of Marquette University Law School

M a r q u e t t e u niversity Law s c h o o L Magazine Fa L L 2 0 1 0 eckstein hall opens Dean Kearney welcomes archbishop Dolan A ls o I n si d e : daniel d. Blinka on the changing role of trials and witnesses of new york, chief Justice abrahamson, and Matthew J. Mitten on taxing college football Justice scalia to Dedication Biskupic, Brennan, dressler, Meine, Sykes Faculty blog: Paul Robeson, Lady Gaga, and the breakdown $85 Million Project Sets Stage for Law School’s Future of social order n A e d t h e Laying the Foundation M o R F It is not unusual for me to invite you to read the Marquette University campus, where Lincoln latest issue of Marquette Lawyer. I am more self- stressed the importance of reading: “A capacity, conscious of it now because reading is much on and taste, for reading, gives access to whatever my mind. has already been discovered by others. It is the First, we have dedicated Ray and Kay Eckstein key, or one of the keys, to the already solved Hall—a building for whose exterior we set the problems. And not only so. It gives a relish, goal of being noble, bold, harmonious, dramatic, and facility, for successfully pursuing the yet confident, slightly willful, and, in a word, unsolved ones.” This speech helped inspire great; whose interior we wanted to be open our Legacies of Lincoln Conference, held last to the community and conducive to a sense of October to commemorate the sesquicentennial community; and that we intended would be, in of Lincoln’s Milwaukee speech and the Ithe aggregate, the best law school building in the bicentennial of his birth; papers from the country. -

Judicial Branch

Judicial 7 Branch The judicial branch: profile of the judicial branch, summary of recent significant supreme court decisions, and descriptions of the supreme court, court system, and judicial service agencies 1870 Senate (State Historical Society, #WHi 46794) 578 WISCONSIN BLUE BOOK 2007 − 2008 WISCONSIN SUPREME COURT Current Term First Assumed Began First Expires Justice Office Elected Term July 31 Shirley S. Abrahamson, Chief Justice . 1976* August 1979 2009 Jon P. Wilcox** . 1992* August 1997 2007 Ann Walsh Bradley . 1995 August 1995 2015 N. Patrick Crooks . 1996 August 1996 2016 David T. Prosser, Jr. 1998* August 2001 2011 Patience Drake Roggensack . 2003 August 2003 2013 Louis B. Butler, Jr. 2004* −−− 2008 Annette K. Ziegler** . 2007 August 2007 2017 *Initially appointed by the governor. **Annette K. Ziegler was elected to the Supreme Court on April 3, 2007, to fill a seat held by Justice Jon P. Wilcox, who did not seek reelection. Sources: 2005-2006 Wisconsin Statutes; Director of State Courts, departmental data, April 2007; Wisconsin Court System, Supreme Court Justices, at: http://www.wicourts.gov/about/judges/supreme/index.htm The Chamber of the Supreme Court is located in the East Wing of the State Capitol. The mural above the justices, one of four in the chamber, depicts the signing of the U.S. Constitution, painted by Albert Herter. Pictured from left to right are Justice Patience D. Roggensack, Justice N. Patrick Crooks, retired Justice Jon P. Wilcox, Chief Justice Shirley S. Abrahamson, Justice Ann Walsh Bradley, Justice David T. Prosser, Jr., and Justice Louis B. Butler, Jr. Not pictured is Justice Annette K. -

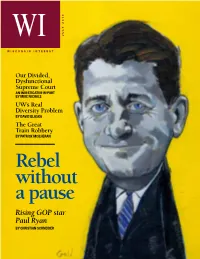

Rebel Without a Pause Rising GOP Star Paul Ryan by Christian Schneider Editor > Charles J

WI 2010 JULY WISCONSIN INTEREST Our Divided, Dysfunctional Supreme Court AN INVESTIGATIVE REPORT BY MIKE NICHOLS UW’s Real Diversity Problem BY DAVID BLASKA The Great Train Robbery BY PATRICK MCILHERAN Rebel without a pause Rising GOP star Paul Ryan BY CHRISTIAN SCHNEIDER Editor > CHARLES J. SYKES Hard choices WI WISCONSIN INTEREST For a rising political star, Paul Ryan remains a nation’s foremost celebrity wonk, asking: remarkably lonely political figure. For years, “What’s so damn special about Paul Ryan?” under both Democrats and Republicans, he More than his matinee-idol looks. has warned about the need to avert a fiscal “Ryan is a throwback,” writes Schneider, Publisher: meltdown, but even though his detailed “he could easily have been a conservative Wisconsin Policy Research Institute, Inc. “Roadmap” for restraining government politician in the era before cable news. He spending was widely praised, it was embraced has risen to national stardom by taking the Editor: Charles J. Sykes by very few. path least traveled by modern politicians: He Despite lip-service praise from President knows a lot of stuff.” Managing Editor: Marc Eisen Obama, Democrats have launched serial Also in this issue, Mike Nichols examines Art Direction: attacks against the plan, while GOP leaders Wisconsin’s dysfunctional, divided Supreme Stephan & Brady, Inc. have made themselves scarce, avoiding being Court and the implications for law in the state. Contributors: yoked to the specificity of Ryan’s hard choices. Patrick McIlheran deconstructs the state’s David Blaska But Ryan’s warnings have taken on new signature boondoggle, the billion-dollar not- Richard Esenberg urgency as Europe’s debt crisis unfolds, and so-fast train from Milwaukee to somewhere Patrick McIlheran the U.S.