THE Hong Kong ACTION HERO in Zhang YIMOU-DIRECTED HERO

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

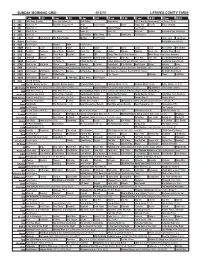

Sunday Morning Grid 4/12/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 4/12/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Bull Riding Remembers 2015 Masters Tournament Final Round. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News Paid Program Luna! Poppy Cat Tree Fu Figure Skating 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Explore Incredible Dog Challenge 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program I Love Lucy I Love Lucy 13 MyNet Paid Program Red Lights ›› (2012) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Cosas Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local RescueBot RescueBot 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Cooking Chefs Life Simply Ming Lidia 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News TBA Things That Aren’t Here Anymore More Things Aren’t Here Anymore 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki (TVY) Doki Ad Dive, Olly Dive, Olly E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial 34 KMEX Paid Program Al Punto (N) Fútbol Central (N) Fútbol Mexicano Primera División: Toluca vs Atlas República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Best Praise Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program Hocus Pocus ›› (1993) Bette Midler. -

Sight & Sound Films of 2007

Sight & Sound Films of 2007 Each year we ask a selection of our contributors - reviewers and critics from around the world - for their five films of the year. It's a very loosely policed subjective selection, based on films the writer has seen and enjoyed that year, and we don't deny them the choice of films that haven't yet reached the UK. And we don't give them much time to ponder, either - just about a week. So below you'll find the familiar and the obscure, the new and the old. From this we put together the top ten you see here. What distinguishes this particular list is that it's been drawn up from one of the best years for all-round quality I can remember. 2007 has seen some extraordinary films. So all of the films in the ten are must-sees and so are many more. Enjoy. - Nick James, Editor. 1 4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days (Cristian Mungiu) 2 Inland Empire (David Lynch) 3 Zodiac (David Fincher) = 4 I’m Not There (Todd Haynes) The Lives of Others (Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck) 6 Silent Light (Carlos Reygadas) = 7 The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford (Andrew Dominik) Syndromes and a Century (Apichatpong Weerasethakul) No Country for Old Men (Ethan and Joel Coen) Eastern Promises (David Cronenberg) 1 Table of Contents – alphabetical by critic Gilbert Adair (Critic and author, UK)............................................................................................4 Kaleem Aftab (Critic, The Independent, UK)...............................................................................4 Geoff Andrew (Critic -

Jet Li Workout Routine

JET LI WORKOUT ROUTINE Bonus PDF File By: Mike Romaine Copyright Notice No part of this report may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any informational storage or retrieval system without expressed written, dated and signed permission from the author. All copyrights are reserved. Disclaimer and/or Legal Notices The information provided in this book is for educational purposes only. I am not a doctor and this is not meant to be taken as medical advice. The information provided in this book is based upon my experiences as well as my interpretations of the current research available. The advice and tips given in this course are meant for healthy adults only. You should consult your physician to insure the tips given in this course are appropriate for your individual circumstances. If you have any health issues or pre-existing conditions, please consult with your physician before implementing any of the information provided in this course. This product is for informational purposes only and the author does not accept any responsibilities for any liabilities or damages, real or perceived, resulting from the use of this information. JET LI WORKOUT ROUTINE Training Volume: 5+ days per week Explanation: I’m going to build you a calisthenics program that you can follow 3-5 days per week, and then I will also be sharing his self-defense and training secrets below as well. Want To Upgrade This Workout? The Superhero Academy now comes with an Upgrade Your Workout Tool that allows Academy members to turn any SHJ workout into a 4-8 week fully planned regime detailing exact weights to lift and including reverse & tradition pyramid training, straight sets, super sets, progressive overload and more. -

Spectre, Connoting a Denied That This Was a Reference to the Earlier Films

Key Terms and Consider INTERTEXTUALITY Consider NARRATIVE conventions The white tuxedo intertextually references earlier Bond Behind Bond, image of a man wearing a skeleton mask and films (previous Bonds, including Roger Moore, have worn bone design on his jacket. Skeleton has connotations of Central image, protag- the white tuxedo, however this poster specifically refer- death and danger and the mask is covering up someone’s onist, hero, villain, title, ences Sean Connery in Goldfinger), providing a sense of identity, someone who wishes to remain hidden, someone star appeal, credit block, familiarity, nostalgia and pleasure to fans who recognise lurking in the shadows. It is quite easy to guess that this char- frame, enigma codes, the link. acter would be Propp’s villain and his mask that is reminis- signify, Long shot, facial Bond films have often deliberately referenced earlier films cent of such holidays as Halloween or Day of the Dead means expression, body lan- in the franchise, for example the ‘Bond girl’ emerging he is Bond’s antagonist and no doubt wants to kill him. This guage, colour, enigma from the sea (Ursula Andress in Dr No and Halle Berry in acts as an enigma code for theaudience as we want to find codes. Die Another Day). Daniel Craig also emerged from the sea out who this character is and why he wants Bond. The skele- in Casino Royale, his first outing as Bond, however it was ton also references the title of the film, Spectre, connoting a denied that this was a reference to the earlier films. ghostly, haunting presence from Bond’s past. -

Unbelievable Bodies: Audience Readings of Action Heroines As a Post-Feminist Visual Metaphor

Unbelievable Bodies: Audience Readings of Action Heroines as a Post-Feminist Visual Metaphor Jennifer McClearen A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts University of Washington 2013 Committee: Ralina Joseph, Chair LeiLani Nishime Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Communication ©Copyright 2013 Jennifer McClearen Running head: AUDIENCE READINGS OF ACTION HEROINES University of Washington Abstract Unbelievable Bodies: Audience Readings of Action Heroines as a Post-Feminist Visual Metaphor Jennifer McClearen Chair of Supervisory Committee: Associate Professor Ralina Joseph Department of Communication In this paper, I employ a feminist approach to audience research and examine the individual interviews of 11 undergraduate women who regularly watch and enjoy action heroine films. Participants in the study articulate action heroines as visual metaphors for career and academic success and take pleasure in seeing women succeed against adversity. However, they are reluctant to believe that the female bodies onscreen are physically capable of the action they perform when compared with male counterparts—a belief based on post-feminist assumptions of the limits of female physical abilities and the persistent representations of thin action heroines in film. I argue that post-feminist ideology encourages women to imagine action heroines as successful in intellectual arenas; yet, the ideology simultaneously disciplines action heroine bodies to render them unbelievable as physically powerful women. -

'The Whole Burden of Civilisation Has Fallen Upon Us'

‘The Whole Burden of Civilisation Has Fallen upon Us’. The Representation of Gender in Zombie Films, 1968-2013 Leon van Amsterdam Student number: s1141627 Leiden University MA History: Cities, Migration and Global Interdependence Thesis supervisor: Marion Pluskota 2 Contents Chapter 1: Introduction .............................................................................................................. 4 Theory ................................................................................................................................. 6 Literature Review ............................................................................................................... 9 Material ............................................................................................................................ 13 Method ............................................................................................................................. 15 Chapter 2: A history of the zombie and its cultural significance ............................................. 18 Race and gender representations in early zombie films .................................................. 18 The sci-fi zombie and Romero’s ghoulish zombie ............................................................ 22 The loss and return of social anxiety in the zombie genre .............................................. 26 Chapter 3: (Post)feminism in American politics and films ....................................................... 30 Protofeminism ................................................................................................................. -

Yao Ming Still Most Engaging Chinese Celebrity : R3 by David Blecken on Mar 31, 2011 (5 Hours Ago) Filed Under Marketing, China

# 页码,1/4 Network Asia-Pacific Know it now... News People Video Blogs & Opinions Rankings & Research Creativity Marketing Home / Marketing / Rankings & Research / Research Reports Yao Ming still most engaging Chinese celebrity : R3 By David Blecken on Mar 31, 2011 (5 hours ago) filed under Marketing, China BEIJING – Yao Ming remains China’s most popular celebrity, closely followed by hurdler Liu Xiang and Jackie Chan, according to Enspire, a study by marketing consultancy R3. KEYWORDS yao ming, liu xiang, jackie chan, r3, enspire, celebrity, china AGENCY r3 INDUSTRY marketing RELATED Yao Ming's popularity is linked to his attitude towards CSR NBA star Yao Ming partners with Monster Cable to Kobe Bryant was the only foreign celebrity to make the top thirty ranking, launch Yao Monster coming in eighth. Other prominent personalities within the top 10 were Andy Sprite rolls out 'green Lau, Faye Wong, Jet Li, Leehom Wang, Jacky Cheung and Jay Chou. carpet' for China premier of The Green Hornet However, the calculated value of the top two stars was significantly higher than Maxus Guangzhou seals http://en.campaignchina.com/Article/252958,yao-ming-still-most-eng... 2011-03-31 # 页码,2/4 Maxus Guangzhou seals Ping An Insurance Group’ the others. Both Yao and Liu received a value rating of more than 130, while s two-year media contract Chan was valued at 68. Provincial China still largely untapped : Nielsen Sunny Chen, a senior researcher at the company, attributed Yao’s popularity to his perceived prowess as a sports person, his “strong moral values” and Porsche calls pitch in China active participation in corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives. -

Donnie Yen's Kung Fu Persona in Hypermedia

Studies in Media and Communication Vol. 4, No. 2; December 2016 ISSN 2325-8071 E-ISSN 2325-808X Published by Redfame Publishing URL: http://smc.redfame.com Remediating the Star Body: Donnie Yen’s Kung Fu Persona in Hypermedia Dorothy Wai-sim Lau1 113/F, Hong Kong Baptist University Shek Mun Campus, 8 On Muk Street, Shek Mun, Shatin, Hong Kong Correspondence: Dorothy Wai-sim Lau, 13/F, Hong Kong Baptist University Shek Mun Campus, 8 On Muk Street, Shek Mun, Shatin, Hong Kong. Received: September 18, 2016 Accepted: October 7, 2016 Online Published: October 24, 2016 doi:10.11114/smc.v4i2.1943 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.11114/smc.v4i2.1943 Abstract Latest decades have witnessed the proliferation of digital media in Hong Kong action-based genre films, elevating the graphical display of screen action to new levels. While digital effects are tools to assist the action performance of non-kung fu actors, Dragon Tiger Gate (2006), a comic-turned movie, becomes a case-in-point that it applies digitality to Yen, a celebrated kung fu star who is famed by his genuine martial dexterity. In the framework of remediation, this essay will explore how the digital media intervene of the star construction of Donnie Yen. As Dragon Tiger Gate reveals, technological effects work to refashion and repurpose Yen’s persona by combining digital effects and the kung fu body. While the narrative of pain and injury reveals the attempt of visual immediacy, the hybridized bodily representation evokes awareness more to the act of representing kung fu than to the kung fu itself. -

8 Redefining Zorro: Hispanicising the Swashbuckling Hero

Redefining Zorro: Hispanicising the Swashbuckling Hero Victoria Kearley Introduction Such did the theatrical trailer for The Mask of Zorro (Campbell, 1998) proclaim of Antonio Banderas’s performance as the masked adventurer, promising the viewer a sexier and more daring vision of Zorro than they had ever seen before. This paper considers this new image of Zorro and the way in which an iconic figure of modern popular culture was redefined through the performance of Banderas, and the influence of his contemporary star persona, as he became the first Hispanic actor ever to play Zorro in a major Hollywood production. It is my argument that Banderas’s Zorro, transformed from bandit Alejandro Murrieta into the masked hero over the course of the film’s narrative, is necessarily altered from previous incarnations in line with existing Hollywood images of Hispanic masculinity when he is played by a Hispanic actor. I will begin with a short introduction to the screen history of Zorro as a character and outline the action- adventure hero archetype of which he is a prime example. The main body of my argument is organised around a discussion of the employment of three of Hollywood’s most prevalent and enduring Hispanic male types, as defined by Latino film scholar, Charles Ramirez Berg, before concluding with a consideration of how these ultimately serve to redefine the character. Who is Zorro? Zorro was originally created by pulp fiction writer, Johnston McCulley, in 1919 and first immortalised on screen by Douglas Fairbanks in The Mark of Zorro (Niblo, 1920) just a year later. -

Recommended Films: a Preparation for a Level Film Studies

Preparation for A-Level Film Studies: First and foremost a knowledge of film is needed for this course, often in lessons, teachers will reference films other than the ones being studied. Ideally you should be watching films regularly, not just the big mainstream films, but also a range of films both old and new. We have put together a list of highly useful films to have watched. We recommend you begin watching some these, as and where you can. There are also a great many online lists of ‘greatest films of all time’, which are worth looking through. Citizen Kane: Orson Welles 1941 Arguably the greatest film ever made and often features at the top of film critic and film historian lists. Welles is also regarded as one the greatest filmmakers and in this film: he directed, wrote and starred. It pioneered numerous film making techniques and is oft parodied, it is one of the best. It’s a Wonderful Life: Frank Capra, 1946 One of my personal favourite films and one I watch every Christmas. It’s a Wonderful Life is another film which often appears high on lists of greatest films, it is a genuinely happy and uplifting film without being too sweet. James Stewart is one of the best actors of his generation and this is one of his strongest performances. Casablanca: Michael Curtiz, 1942 This is a masterclass in storytelling, staring Humphrey Bogart and Ingrid Bergman. It probably has some of the most memorable lines of dialogue for its time including, ‘here’s looking at you’ and ‘of all the gin joints in all the towns in all the world, she walks into mine’. -

Character Roles in the Estonian Versions of the Dragon Slayer (At 300)

“THE THREE SUITORS OF THE KING’S DAUGHTER”: CHARACTER ROLES IN THE ESTONIAN VERSIONS OF THE DRAGON SLAYER (AT 300) Risto Järv The first fairy tale type (AT 300) in the Aarne-Thompson type in- dex, the fight of a hero with the mythical dragon, has provided material for both the sacred as well as the profane kind of fabulated stories, for myth as well as fairy tale. The myth of dragon-slaying can be met in all mythologies in which the dragon appears as an independent being. By killing the dragon the hero frees the water it has swallowed, gets hold of a treasure it has guarded, or frees a person, who in most cases is a young maiden that has been kidnapped (MNM: 394). Lutz Rörich (1981: 788) has noted that dragon slaying often marks a certain liminal situation – the creation of an order (a city, a state, an epoch or a religion) or the ending of something. The dragon’s appearance at the beginning or end of the sacral nar- rative, as well as its dimensions ‘that surpass everything’ show that it is located at an utmost limit and that a fight with it is a fight in the superlative. Thus, fighting the dragon can signify a universal general principle, the overcoming of anything evil by anything good. In Christianity the defeating of the dragon came to symbolize the overcoming of paganism and was employed in saint legends. The honour of defeating the dragon has been attributed to more than sixty different Catholic saints. In the Christian canon it was St. -

NATO Feb 05 NL.Indd

February 2005 NANATOTO of California/NevadaCalifornia/Nevada Information for the California and Nevada Motion Picture Theatre Industry THE CALIFORNIA POPCORN TAX CALENDAR By Duane Sharpe, Hutchinson and Bloodgood LLP of EVENTS & The California State Board of Equalization (the Board) recently issued an Opinion on a refund HOLIDAYS of sales tax to a local theatre chain (hereafter, the Theatre). The detail of the refund wasn’t discussed in the opinion, but the Board did focus on two specifi c issues that affected the refund. February 6 California tax law requires the assessment of sales tax on the sale of all food products when sold Super Bowl Sunday for consumption within a place that charges admission. The Board noted that in all but one loca- tion, the Theatre had changed their operations regarding admissions to its theatre buildings. Instead February 12 of requiring customers to fi rst purchase tickets to enter into the theatre building lobby in which all Lincoln’s Birthday food and drinks were sold, the Theatre opened each lobby to the general public without requiring tickets. The Theatre only required tickets for the customers to enter further into the inside movie February 14 viewing areas of the theatres. This admission policy allowed the Theatre not to charge sales tax on Valentine’s Day “popcorn sales.” California tax law requires the assessment of sales tax on the sale of “hot prepared food products.” The issue before the Board was whether the popcorn sold by the Theatre was a hot February 21 prepared food product. President’s Day From the Opinion: “Claimant’s process for making popcorn starts with a popper.