Storm Wind Loads & Tree Damage by Dr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Storm Wind Loads on Trees Thought by the Author to Provide the Best Means for Considering Fundamental Tree Health Care Issues Surrounding Tree Biomechanics

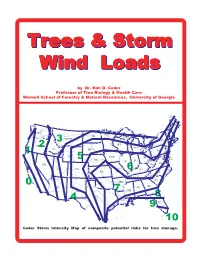

TreesTreesTrees &&& StormStormStorm WindWindWind LoadsLoadsLoads by Dr. Kim D. Coder Professor of Tree Biology & Health Care Warnell School of Forestry & Natural Resources, University of Georgia MAINE WASH. MN. VT. ND. NH. MICH. MONT. MASS. NY. 3 CT. RI. OR. WS. MICH. 2 NJ. ID. 1 SD. PA. WY. IOWA OH. DL. 5 NB. MD. IL. IN. W. NV. VA . VA . UT. CO. 6 KY. KS. MO. NC. CA. TN. SC. ARK. OK. 0 GA. AZ. AL. NM. 7 MS. TX. 8 4 LA. 9 FL. 10 Coder Storm Intensity Map of composite potential risks for tree damage. This publication is an educational product designed for helping tree professionals appreciate and understand basic aspects of tree mechanical loading during storms. This educational product is a synthesis and integration of weather data and educational concepts regarding how storms wind loads impact trees. This product is for awareness building and educational development. At the time it was finished, this publication contained information regarding storm wind loads on trees thought by the author to provide the best means for considering fundamental tree health care issues surrounding tree biomechanics. The University of Georgia, the Warnell School of Forestry & Natural Resources, and the author are not responsible for any errors, omissions, misinterpretations, or misapplications from this educational product. The author assumed professional users would have some basic tree structure and mechanics background. This product was not designed, nor is suited, for homeowner use. Always seek the advice and assistance of professional tree health providers for tree care and structural assessments. This educational product is only for noncommercial, nonprofit use and may not be copied or reproduced by any means, in any format, or in any media including electronic forms, without explicit written permission of the author. -

What Are We Doing with (Or To) the F-Scale?

5.6 What Are We Doing with (or to) the F-Scale? Daniel McCarthy, Joseph Schaefer and Roger Edwards NOAA/NWS Storm Prediction Center Norman, OK 1. Introduction Dr. T. Theodore Fujita developed the F- Scale, or Fujita Scale, in 1971 to provide a way to compare mesoscale windstorms by estimating the wind speed in hurricanes or tornadoes through an evaluation of the observed damage (Fujita 1971). Fujita grouped wind damage into six categories of increasing devastation (F0 through F5). Then for each damage class, he estimated the wind speed range capable of causing the damage. When deriving the scale, Fujita cunningly bridged the speeds between the Beaufort Scale (Huler 2005) used to estimate wind speeds through hurricane intensity and the Mach scale for near sonic speed winds. Fujita developed the following equation to estimate the wind speed associated with the damage produced by a tornado: Figure 1: Fujita's plot of how the F-Scale V = 14.1(F+2)3/2 connects with the Beaufort Scale and Mach number. From Fujita’s SMRP No. 91, 1971. where V is the speed in miles per hour, and F is the F-category of the damage. This Amazingly, the University of Oklahoma equation led to the graph devised by Fujita Doppler-On-Wheels measured up to 318 in Figure 1. mph flow some tens of meters above the ground in this tornado (Burgess et. al, 2002). Fujita and his staff used this scale to map out and analyze 148 tornadoes in the Super 2. Early Applications Tornado Outbreak of 3-4 April 1974. -

Fish & Wildlife Branch Research Permit Environmental Condition

Fish & Wildlife Branch Research Permit Environmental Condition Standards Fish and Wildlife Branch Technical Report No. 2013-21 December 2013 Fish & Wildlife Branch Scientific Research Permit Environmental Condition Standards First Edition 2013 PUBLISHED BY: Fish and Wildlife Branch Ministry of Environment 3211 Albert Street Regina, Saskatchewan S4S 5W6 SUGGESTED CITATION FOR THIS MANUAL: Saskatchewan Ministry of Environment. 2013. Fish & Wildlife Branch scientific research permit environmental condition standards. Fish and Wildlife Branch Technical Report No. 2013-21. 3211 Albert Street, Regina, Saskatchewan. 60 pp. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS: Fish & Wildlife Branch scientific research permit environmental condition standards: The Research Permit Process Renewal working group (Karyn Scalise, Sue McAdam, Ben Sawa, Jeff Keith and Ed Beveridge) compiled the information found in this document to provide necessary information regarding species protocol environmental condition parameters. COVER PHOTO CREDITS: http://www.freepik.com/free-vector/weather-icons-vector- graphic_596650.htm CONTENT PHOTO CREDITS: as referenced CONTACT: [email protected] COPYRIGHT Brand and product names mentioned in this document are trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective holders. Use of brand names does not constitute an endorsement. Except as noted, all illustrations are copyright 2013, Ministry of Environment. ii Contents Introduction ....................................................................................................................... -

Storms Are Thunderstorms That Produce Tornadoes, Large Hail Or Are Accompanied by High Winds

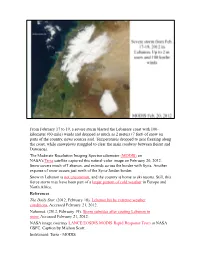

From February 17 to 19, a severe storm blasted the Lebanese coast with 100- kilometer (60-mile) winds and dropped as much as 2 meters (7 feet) of snow on parts of the country, news sources said. Temperatures dropped to near freezing along the coast, while snowplows struggled to clear the main roadway between Beirut and Damascus. The Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on NASA’s Terra satellite captured this natural-color image on February 20, 2012. Snow covers much of Lebanon, and extends across the border with Syria. Another expanse of snow occurs just north of the Syria-Jordan border. Snow in Lebanon is not uncommon, and the country is home to ski resorts. Still, this fierce storm may have been part of a larger pattern of cold weather in Europe and North Africa. References The Daily Star. (2012, February 18). Lebanon hit by extreme weather conditions. Accessed February 21, 2012. Naharnet. (2012, February 19). Storm subsides after coating Lebanon in snow. Accessed February 21, 2012. NASA image courtesy LANCE/EOSDIS MODIS Rapid Response Team at NASA GSFC. Caption by Michon Scott. Instrument: Terra - MODIS Flooding is the most common of all natural hazards. Each year, more deaths are caused by flooding than any other thunderstorm related hazard. We think this is because people tend to underestimate the force and power of water. Six inches of fast-moving water can knock you off your feet. Water 24 inches deep can carry away most automobiles. Nearly half of all flash flood deaths occur in automobiles as they are swept downstream. -

Massachusetts Tropical Cyclone Profile August 2021

Commonwealth of Massachusetts Tropical Cyclone Profile August 2021 Commonwealth of Massachusetts Tropical Cyclone Profile Description Tropical cyclones, a general term for tropical storms and hurricanes, are low pressure systems that usually form over the tropics. These storms are referred to as “cyclones” due to their rotation. Tropical cyclones are among the most powerful and destructive meteorological systems on earth. Their destructive phenomena include storm surge, high winds, heavy rain, tornadoes, and rip currents. As tropical storms move inland, they can cause severe flooding, downed trees and power lines, and structural damage. Once a tropical cyclone no longer has tropical characteristics, it is then classified as a post-tropical system. The National Hurricane Center (NHC) has classified four stages of tropical cyclones: • Tropical Depression: A tropical cyclone with maximum sustained winds of 38 mph (33 knots) or less. • Tropical Storm: A tropical cyclone with maximum sustained winds of 39 to 73 mph (34 to 63 knots). • Hurricane: A tropical cyclone with maximum sustained winds of 74 mph (64 knots) or higher. • Major Hurricane: A tropical cyclone with maximum sustained winds of 111 mph (96 knots) or higher, corresponding to a Category 3, 4 or 5 on the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale. Primary Hazards Storm Surge and Storm Tide Storm surge is an abnormal rise of water generated by a storm, over and above the predicted astronomical tide. Storm surge and large waves produced by hurricanes pose the greatest threat to life and property along the coast. They also pose a significant risk for drowning. Storm tide is the total water level rise during a storm due to the combination of storm surge and the astronomical tide. -

The Enhanced Fujita Tornado Scale

NCDC: Educational Topics: Enhanced Fujita Scale Page 1 of 3 DOC NOAA NESDIS NCDC > > > Search Field: Search NCDC Education / EF Tornado Scale / Tornado Climatology / Search NCDC The Enhanced Fujita Tornado Scale Wind speeds in tornadoes range from values below that of weak hurricane speeds to more than 300 miles per hour! Unlike hurricanes, which produce wind speeds of generally lesser values over relatively widespread areas (when compared to tornadoes), the maximum winds in tornadoes are often confined to extremely small areas and can vary tremendously over very short distances, even within the funnel itself. The tales of complete destruction of one house next to one that is totally undamaged are true and well-documented. The Original Fujita Tornado Scale In 1971, Dr. T. Theodore Fujita of the University of Chicago devised a six-category scale to classify U.S. tornadoes into six damage categories, called F0-F5. F0 describes the weakest tornadoes and F5 describes only the most destructive tornadoes. The Fujita tornado scale (or the "F-scale") has subsequently become the definitive scale for estimating wind speeds within tornadoes based upon the damage caused by the tornado. It is used extensively by the National Weather Service in investigating tornadoes, by scientists studying the behavior and climatology of tornadoes, and by engineers correlating damage to different types of structures with different estimated tornado wind speeds. The original Fujita scale bridges the gap between the Beaufort Wind Speed Scale and Mach numbers (ratio of the speed of an object to the speed of sound) by connecting Beaufort Force 12 with Mach 1 in twelve steps. -

Indicative Hazard Profile for Strong Winds in South Africa Page 1 of 11

Research Article Indicative hazard profile for strong winds in South Africa Page 1 of 11 Indicative hazard profile for strong winds in AUTHORS: South Africa Andries C. Kruger1 Dechlan L. Pillay2 Mark van Staden2 While various extreme wind studies have been undertaken for South Africa for the purpose of, amongst others, developing strong wind statistics, disaster models for the built environment and estimations of AFFILIATIONS: tornado risk, a general analysis of the strong wind hazard in South Africa according to the requirements of 1South African Weather Service, the National Disaster Management Centre is needed. The purpose of the research was to develop a national Pretoria, South Africa profile of the wind hazard in the country for eventual input into a national indicative risk and vulnerability 2 Early Warnings and Capability profile. An analysis was undertaken with data from the South African Weather Service’s long-term weather Management Systems, National Disaster Management Centre, stations to quantify the wind hazard on a municipal scale, taking into account that there are more than 220 Centurion, South Africa municipalities in South Africa. South Africa is influenced by various strong wind mechanisms occurring at various spatial and temporal scales. This influence is reflected in the results of the analyses which indicated CORRESPONDENCE TO: that the wind hazard across South Africa is highly variable, spatially and seasonally. A general result was Andries Kruger that the strong wind hazard is highest from the southwestern Cape towards the central and eastern parts of the Northern Cape Province, and the southeastern parts of the coast as well as the eastern interior of the EMAIL: Andries.Kruger@weathersa. -

View Document

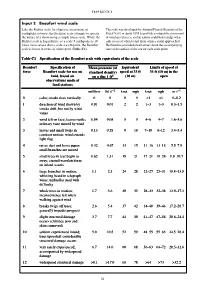

T839 BLOCK 3 Input 2 Beaufort wind scale Like the Richter scale for objective assessment of The scale was developed by Admiral Francis Beaufort of the earthquake severity, the Beaufort scale attempts to specify Royal Navy in about 1805 to provide an objective assessment the nature of a storm using a simple linear scale. While the of wind speed at sea, so that sailors could better judge what Richter scale is logarithmic, so a scale 5 earthquake is 10 sails to use or when to furl them when a storm approached. times more severe than a scale 4 earthquake, the Beaufort He therefore provided observations about the accompanying scale is linear in terms of wind speed (Table C1). state of the surface of the sea for each scale point. Table C1 Specification of the Beaufort scale with equivalents of the scale Beaufort Specification of Mean pressure (at Equivalent Limits of speed at force Beaufort scale for use on standard density) speed at 33 ft 33 ft (10 m) in the land, based on on a disc 1 ft2 (10 m) open observations made at land stations millibar lbf ft−2 knot mph knot mph m s−1 0 calm; smoke rises vertically 0 0 0 0 <1 <1 0–0.2 1 direction of wind shown by 0.01 0.01 2 2 1–3 1–3 0.3–1.5 smoke drift, but not by wind vanes 2 wind felt on face; leaves rustle; 0.04 0.08 5 5 4–6 4–7 1.6–3.6 ordinary vane moved by wind 3 leaves and small twigs in 0.13 0.28 9 10 7–10 8–12 3.4–5.4 constant motion; wind extends light flag 4 raises dust and loose paper; 0.32 0.67 13 15 11–16 13–18 5.5–7.9 small branches are moved 5 small trees in leaf begin to 0.62 1.31 -

Finding Storm Track Activity Metrics That Are Highly Correlated with Weather Impacts

1DECEMBER 2020 Y A U A N D C H A N G 10169 Finding Storm Track Activity Metrics That Are Highly Correlated with Weather Impacts. Part I: Frameworks for Evaluation and Accumulated Track Activity ALBERT MAN-WAI YAU AND EDMUND KAR-MAN CHANG School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences, Stony Brook University, State University of New York, Stony Brook, New York (Manuscript received 29 May 2020, in final form 10 August 2020) ABSTRACT: In the midlatitudes, storm tracks give rise to much of the high-impact weather, including precipitation and strong winds. Numerous metrics have been used to quantify storm track activity, but there has not been any systematic evaluation of how well different metrics relate to weather impacts. In this study, two frameworks have been developed to provide such evaluations. The first framework quantifies the maximum one-point correlation between weather impacts at each grid point and the assessed storm track metric. The second makes use of canonical correlation analysis to find the best correlated patterns and uses these patterns to hindcast weather impacts based on storm track metric anomalies using a leave- N-out cross-validation approach. These two approaches have been applied to assess multiple Eulerian variances and Lagrangian tracking statistics for Europe, using monthly precipitation and a near-surface high-wind index as the assessment criteria. The results indicate that near-surface storm track metrics generally relate more closely to weather impacts than upper-tropospheric metrics. For Eulerian metrics, synoptic time scale eddy kinetic energy at 850 hPa relates strongly to both precipitation and wind impacts. -

1.1 the Climatology of Inland Winds from Tropical Cyclones in the Eastern United States

1.1 THE CLIMATOLOGY OF INLAND WINDS FROM TROPICAL CYCLONES IN THE EASTERN UNITED STATES Michael C. Kruk* STG Inc., Asheville, North Carolina Ethan J. Gibney IMSG Inc., Asheville, North Carolina David H. Levinson and Michael Squires NOAA National Climatic Data Center, Asheville, NC landfall than do weaker storms. For these reasons, the 1. Introduction primary impact areas of tropical cyclones are generally found along coastal (or near coastal) regions. Most In the United States, the impacts from tropical previous studies involving the inland-extent of tropical cyclones often extend well-inland after these storms cyclones have generally focused on their expected or make landfall along the coast. For example, after the modeled rate of decay post landfall (e.g., Tuleya et al. passage of Hurricane Camille (1969), more than 150 1984, Kaplan and DeMaria 1995; Kaplan and DeMaria casualties occurred in the state of Virginia, some 1300 2001), while others have focused on recurrence km inland from where the storm originally made landfall thresholds or probabilities of landfalls along a given along the Louisiana coast (Emanuel 2005). According to portion of the United States coastline (e.g., Bove et al. Rappaport (2000), a large portion of fatalities often occur 1998; Elsner and Bossak 2001; Gray and Klotzbach inland associated with a decaying tropical cyclone’s 2005; Saunders and Lea 2005). Results from Kaplan winds (falling trees, collapsed roofs, etc.) and heavy and DeMaria (1995) showed an idealized scenario for flooding rains. In the 1970s, ‘80s, and ‘90s, freshwater the maximum possible inland wind speed of a decaying floods accounted for 59 percent of the recorded deaths tropical cyclone based on both intensity at landfall and from tropical cyclones (Rappaport 2000), and such forward motion for the Gulf Coast and southeastern floods are often a combination of meteorological and United States, and for the New England area (Kaplan hydrological factors. -

Hazus Hurricane Model User Guidance

Hazus Hurricane Model User Guidance April 2018 Document History Affected Section or Date Description Subsection First publication using April 2018 Updated user manual from Hazus version 2.1 to Hazus version this format 4.2. Manual has been reorganized from prior version. Table of Contents 1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................................... 1-1 1.1 Hazus Users and Applications .................................................................................................. 1-1 1.2 Hurricane Model Outputs .......................................................................................................... 1-2 1.3 Assumed User Expertise .......................................................................................................... 1-3 1.4 When to Seek Help ................................................................................................................... 1-4 1.5 Technical Support ..................................................................................................................... 1-4 1.6 Uncertainties in Loss Estimates ............................................................................................... 1-5 1.7 Organization of User Guidance ................................................................................................ 1-5 2 OVERVIEW OF THE HURRICANE MODEL ........................................................................................................ -

1 Orographic Effects on Supercell: Development and Structure

Orographic Effects on Supercell: Development and Structure, Intensity and Tracking Galen M. Smith1, Yuh-Lang Lin1,2,@, and Yevgenii Rastigejev1,3 1Department of Energy and Environmental Systems 2Department of Physics 3Department of Mathematics North Carolina A&T State University March 1, 2016 @Corresponding Author Address: Dr. Yuh-Lang Lin, 302H Gibbs Hall, EES, North Carolina A&T State University, 1601 E. Market St., Greensboro, NC 27411. Email: [email protected]. Web: http://mesolab.ncat.edu Abstract Orographic effects on tornadic supercell development, propagation, and structure are investigated using Cloud Model 1 (CM1) with idealized bell-shaped mountains of various heights and a homogeneous fluid flow with a single sounding. It is found that blocking effects are dominative compared to the terrain-induced environmental heterogeneity downwind of the mountain. The orographic effect shifted the track of the storm towards the the left of storm motion, particularly on the lee side of the mountain, when compared to the track in the case with no mountain. The terrain blocking effect also enhanced the supercells inflow, which was increased more than one hour before the storm approached the terrain peak. This allowed the central region of the storm to exhibit clouds with a greater density of hydrometeors than the control. Moreover, the enhanced inflow increased the areal extent of the supercells precipitation, which, in turn enhanced the cold pool outflow serving to enhance the storm’s updraft until becoming strong enough to undercut and weaken the storm considerably. Another aspect of the orographic effects is that down slope winds produced or enhanced low-level vertical vorticity directly under the updraft when the storm approached the mountain peak.