Tad Szulc, the CIA and Cuba

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Miami Cuban Heritage Collection Finding

University of Miami Cuban Heritage Collection Finding Aid - Tad Szulc Collection of Interview Transcripts (CHC0189) Generated by Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.4.0 Printed: May 21, 2018 Language of description: English University of Miami Cuban Heritage Collection Roberto C. Goizueta Pavilion 1300 Memorial Drive Coral Gables FL United States 33146 Telephone: (305) 284-4900 Fax: (305) 284-4901 Email: [email protected] https://library.miami.edu/chc/ https://atom.library.miami.edu/index.php/chc0189 Tad Szulc Collection of Interview Transcripts Table of contents Summary information ...................................................................................................................................... 3 Administrative history / Biographical sketch .................................................................................................. 3 Scope and content ........................................................................................................................................... 4 Arrangement .................................................................................................................................................... 4 Notes ................................................................................................................................................................ 4 Access points ................................................................................................................................................... 5 Series descriptions .......................................................................................................................................... -

A Strategic Flip-Flop in the Caribbean 63

Hoover Press : EPP 100 DP5 HPEP000100 23-02-00 rev1 page 62 62 William Ratliff and Roger Fontaine U.S. interference in Cuban affairs. In effect it gives him a veto over U.S. policy. Therefore the path of giving U.S. politicians a “way out” won’t in fact work because Castro will twist it to his interests. Better to just do it unilaterally on our own timetable. For the time being it appears U.S. policy will remain reactive—to Castro and to Cuban American pressure groups—irrespective of the interests of Americans and Cubans as a whole. Like parrots, all presi- dential hopefuls in the 2000 presidential elections propose varying ver- sions of the current failed policy. We have made much here of the negative role of the Cuba lobby, but we close by reiterating that their advocacy has not usually been different in kind from that of other pressure groups, simply much more effective. The buck falls on the politicians who cannot see the need for, or are afraid to support, a new policy for the post–cold war world. Notes 1. This presentation of the issues is based on but goes far beyond written testimony—“U.S. Cuban Policy—a New Strategy for the Future”— which the authors presented to the U.S. Senate Foreign Relations Com- mittee on 24 May 1995. We have long advocated this change, beginning with William Ratliff, “The Big Cuba Myth,” San Jose Mercury News,15 December 1992, and William Ratliff and Roger Fontaine, “Foil Castro,” Washington Post, 30 June 1993. -

GOV 291 Cuba in the Post Cold War Era the United States and Cuba Recently “Normalized” Relations, Ending the Last Vestige Of

GOV 291 Cuba in the Post Cold War Era The United States and Cuba recently “normalized” relations, ending the last vestige of the Cold War. The course will offer an examination of the social, economic, and political roots of the Cuban revolution of 1959 and the changes brought about in Cuban politics and society as a result of the revolution. This course is a unique opportunity to study Cuban history and the political and economic system of one of the world's few remaining socialist countries. Students do reading on the historic background of the area under study and then focus on contemporary political, social, and economic issues through meeting with resource people: professors, political activists, and grass roots organizers. The course will be conducted in English but knowledge of Spanish will definitely enhance appreciation of our stay in Cuba and study of Cuban history, politics, and society. Tentative Itinerary: Activities will include: Meet with Cuban University students Attend Cuban cultural events, including a jazz club and baseball game Meet with Cuban academics on a range of topics from economic reforms on the island to US-Cuban relations Visit an urban agricultural farm Travel to Santa Clara to visit the Che Guevara Memorial Meet representatives of Cuban political organizations, including the Federation of Cuban women and a member of parliament Tour the city of Havana including its colonial sector Visits to a school and medical clinic There will be three meetings held prior to departure. Each will last two hours (6 hours) There will be four meetings held after the return from Cuba (8 hours) The dates for these meetings shall be determined. -

Dropping Nuclear Bombs on Spain: the Palomares Accident of 1966

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2006 Dropping Nuclear Bombs on Spain the Palomares Accident of 1966 and the U.S. Airborne Alert John Megara Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY DROPPING NUCLEAR BOMBS ON SPAIN THE PALOMARES ACCIDENT OF 1966 AND THE U.S. AIRBORNE ALERT By JOHN MEGARA A Thesis submitted to the Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2006 The members of the Committee approve the thesis of John Megara defended on March 29, 2006. _______________________________ Max Paul Friedman Professor Directing Thesis _______________________________ Neil Jumonville Committee Member _______________________________ Michael Creswell Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to acknowledge the contribution to this thesis of several hundred people, but for brevity’s sake I will name just three. As members of my advisory committee, Max Paul Friedman, Neil Jumonville and Michael Creswell were not only invaluable in the construction of this work, but were also instrumental in the furthering of my education. I would also like to thank Marcia Gorin and the other research librarians at Florida State University’s Strozier Library for showing me how to use the contents of that building. I realize that I have now named four people instead of three, but brevity should surely take a bow to research librarians for their amazing work. -

Extension of Remarks

May 7, 1984 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS 11191 EXTENSION OF REMARKS A SALUTE TO GLOVER WILKINS He is a member of the Tennessee dence collected by law enforcement officers River Valley Association Board of Di who reasonably and in good faith thought rectors, and has also served on the they were acting lawfully. It reflects a grow HON. BILL CHAPPELL, JR. Small Business Advisory Council for ing concern in the country that the exclu OF FLORIDA sionary rule's unjustified ill effects need to the State of Mississippi. be curbed. IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES In November 1962, he was named In California, for instance, a study con Monday, May 7, 1984 Administrator of the Tennessee-Tom ducted by the National Institute of Justice higbee Waterway Development Au found that between 1976 and 1979 more e Mr. CHAPPELL. Mr. Speaker, as thority, his present position. than 4,000 state felony cases were dropped many of my colleagues know, Glover Mr. Speaker, Glover Wilkins is a because of the exclusionary rule. The study Wilkins, Administrator of the Termes man we will be sorry to see leave the also showed that half of those not prosecut see-Tombigbee Waterway Authority, is helm of the Tennessee-Tombigbee Wa ed in 1976 and 1977 because of the exclu retiring. I would like to share with terway Development Authority. It sionary rule were re-arrested during the those who know him, and particularly next two years-on an average of three gives me great pleasure to extend to times apiece. those who do not, the accomplish him best wishes for a happy, healthy The Times editorial erroneously concludes ments achieved by this man over the retirement. -

104-10103-10097.Pdf

This document is made available through the declassification efforts and research of John Greenewald, Jr., creator of: The Black Vault The Black Vault is the largest online Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) document clearinghouse in the world. The research efforts here are responsible for the declassification of hundreds of thousands of pages released by the U.S. Government & Military. Discover the Truth at: http://www.theblackvault.com AMTRUNK Operation - Interim Working Draft, Dated 14 February 1977, with Attachments .. AMTRUNK Operation INTERIM WORKING DRAFT 14 February 1977 1. It is possible that the AMTRUNK Operation might have been a political action operation run against the U.S.G./CIA. (See the separate memorandum on "Operations to Split the Castro Regime .. ") 2. In. late 1962 or early 1963, press.ure was exerted on CIA by Higher Authority (State Department and the White House) to consider a proposal for an on-island operation to split the CASTRO regime. The proposal was presented to Mr. HURWITCH, 1 the State Department Cuban Coordinator, by Tad SZULC (AMCAPE-1) of the New York Times. On 6 February 1963, Albert ·C. DAVIES, (Lt. Col. on military detail to WH/4 - Cuba) met with SZULC 2 . at SZULC's residence, to discuss the plan. SZULC referred to it as the "Leonardo Plan." While at first hesitant, SZULC 3 finally revealed that Dr. Nestor MORENO (AMICE-27) was one of its prime originators. SZULC said that he first thought of bringing the plan to the attention of President KENNEDY~ as he had had a standing invit~tion, s~nce November 1961, for direct contact with President KENNEDY, Attorney General KENNEDY, or Mr. -

Past Maria Moors Cabot Prizes Winners

Last updated: 7/13/20 Past Maria Moors Cabot Prizes Winners: 2019 1. Angela Kocherga, The Albuquerque Journal, Gold Medal, United States 2. Pedro Xavier Molina, Cartoonist, Gold Medal, Nicaragua 3. Boris Muñoz, The New York Times en Español, Gold Medal, United States 4. Marcela Turati, Author and Journalist, Gold Medal, Mexico 5. Armando.Info, Special Citation, Venezuela 2018 1. Hugo Alconada Mon, La Nación, Gold Medal, Argentina 2. Jacqueline Charles, Miami Herald, Gold Medal, United States 3. Graciela Mochkofsky, Craig Newmark Graduate School of Journalism at CUNY, Gold Medal, United States 4. Fernando Rodrigues, Poder360, Gold Medal, Brazil 5. Meridith Kohut, Photojournalism Cover of Venezuela for The New York Times, Citation, United States 2017 1. Martín Caparrós, Writer and Journalist, Gold Medal, Argentina 2. Dorrit Harazim, Journalist, Gold Medal, Brazil 3. Nick Miroff, The Washington Post, Gold Medal, United States 4. Mimi Whitefield, Miami Herald, Gold Medal, United States 2016 1. Rodrigo Abd, The Associated Press, Gold Medal, Peru 2. Rosental Alves, The Knight Center for Journalism, Gold Medal, United States 3. Margarita Martínez, Independent Filmmaker, Gold Medal, Colombia 4. Óscar Martínez, El Faro, Gold Medal, El Salvador 5. Marina Walker Guevara and The Panama Papers Reporting Team, International Consortium of International Journalists, Citation, United States 2015 1. Lucas Mendes, GloboNews, Gold Medal, Brazil 2. Raúl Peñaranda, Página Siete, Gold Medal, Bolivia 1 3. Simon Romero, The New York Times, Gold Medal, United States 4. Mark Stevenson, Associated Press, Gold Medal, United States 5. Ernesto Londoño, The New York Times, Citation, United States 2014 1. Frank Bajak, Chief of the Andean Region, Associated Press, Gold Medal, U.S. -

Baseball Diplomacy, Baseball Deployment: the National

BASEBALL DIPLOMACY, BASEBALL DEPLOYMENT: THE NATIONAL PASTIME IN U.S.-CUBA RELATIONS by JUSTIN W. R. TURNER HOWARD JONES, COMMITTEE CHAIR STEVEN BUNKER LAWRENCE CLAYTON LISA LINDQUIST-DORR RICHARD MEGRAW A DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the Graduate School of The University of Alabama TUSCALOOSA, ALABAMA 2012 Copyright Justin W. R. Turner 2012 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT The game of baseball, a shared cultural affinity linking Cuba and the United States, has played a significant part in the relationship between those nations. Having arrived in Cuba as a symbol of growing American influence during the late nineteenth century, baseball would come to reflect the political and economic connections that developed into the 1900s. By the middle of the twentieth century, a significant baseball exchange saw talented Cuban players channeled into Major League Baseball, and American professionals compete in Cuba’s Winter League. The 1959 Cuban Revolution permanently changed this relationship. Baseball’s politicization as a symbol of the Revolution, coupled with political antagonism, an economic embargo, and an end to diplomatic ties between the Washington and Havana governments largely destroyed the U.S.-Cuba baseball exchange. By the end of the 1960s, Cuban and American baseball interactions were limited to a few international amateur competitions, and political hardball nearly ended some of these. During the 1970s, Cold War détente and the success of Ping Pong Diplomacy with China sparked American efforts to use baseball’s common ground as a basis for improving U.S.-Cuba relations. -

Allen Dulles and the Selling of the CIA in the Aftermath of the Bay of Pigs

bs_bs_banner The Burgeoning Fissures of Dissent: Allen Dulles and the Selling of the CIA in the Aftermath of the Bay of Pigs SIMON WILLMETTS University of Hull Abstract This article documents the efforts of Allen Dulles, upon his forced retirement from the Central Intelligence Agency in the aftermath of the Bay of Pigs, to promote his former agency in the face of mounting public criticism of its activities. It argues that the first wave of critical press regarding the CIA in the early 1960s was an early indication of the breakdown of the Cold War consensus – a phenomenon usually identified as occurring later in the decade in response to the escalation of the Vietnam War. Dulles, who as head of the CIA for most of the 1950s relied upon a compliant media to maintain the CIA’s anonymity in public life, was confronted by an increasingly recalcitrant American media in the following decade that were beginning to question the logics of government secrecy, CIA covert action and US foreign policy more generally. In this respect the Bay of Pigs and the media scrutiny of the CIA and US foreign policy that it inspired can be regarded as an early precursor to the later emergence of adversarial journalism and a post-consensus American culture that contested the Vietnam War and America’s conduct in the Cold War more generally. The very word ‘secrecy’ is repugnant in a free and open society; and we are as a people inherently and historically opposed to secret societies, to secret oaths and to secret proceedings . -

John F. Kennedy

The PRESIDENTIAL RECORDINGS JOHN F. KENNEDY THE GREAT CRISES, VOLUME ONE JULY 30–AUGUST 1962 Timothy Naftali Editor, Volume One George Eliades Francis Gavin Erin Mahan Jonathan Rosenberg David Shreve Associate Editors, Volume One Patricia Dunn Assistant Editor Philip Zelikow and Ernest May General Editors B W. W. NORTON & COMPANY • NEW YORK • LONDON Copyright © 2001 by The Miller Center of Public Affairs Portions of this three-volume set were previously published by Harvard University Press in The Kennedy Tapes: Inside the White House During the Cuban Missile Crisis by Philip D. Zelikow and Ernest R. May. Copyright © 1997 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America First Edition For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110 The text of this book is composed in Bell, with the display set in Bell and Bell Semi-Bold Composition by Tom Ernst Manufacturing by The Maple-Vail Book Manufacturing Group Book design by Dana Sloan Production manager: Andrew Marasia Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data John F. Kennedy : the great crises. p. cm. (The presidential recordings) Includes bibliographical references and indexes. Contents: v. 1. July 30–August 1962 / Timothy Naftali, editor—v. 2. September 4–October 20, 1962 / Timothy Naftali and Philip Zelikow, editors—v. 3. October 22–28, 1962 / Philip Zelikow and Ernest May, editors. ISBN 0-393-04954-X 1. United States—Politics and government—1961–1963—Sources. 2. United States— Foreign relations—1961–1963—Sources. -

Reseña De" the Cuban Revolution: Years of Promise" De Teo A. Babún

Caribbean Studies ISSN: 0008-6533 [email protected] Instituto de Estudios del Caribe Puerto Rico Guerra, Lillian Reseña de "The Cuban Revolution: Years of Promise" de Teo A. Babún y Víctor Andrés Triay Caribbean Studies, vol. 36, núm. 1, enero-junio, 2008, pp. 163-166 Instituto de Estudios del Caribe San Juan, Puerto Rico Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=39214802013 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative RESEÑAS DE LIBROS • BOOKS REVIEWS • COMPTES RENDUS 163 the volume is a catalyst; it forces us to consider human impacts on the island’s environment and what needs to be done to preserve it for the future. While particularly focusing on Puerto Rico, this book punctuates the growing relevance of these issues for the rest of the Caribbean. López Marrero and Villanueva Colón should be commended for their efforts. The maps and raw data in this book offer a wealth of compiled data that will serve researchers as an important reference for the future. Teo A. Babún and Víctor Andrés Triay. 2005.The Cuban Revolution: Years of Promise. Gainesville: University Press of Florida. 117 pp. ISBN: 0-8130-2860-4. Lillian Guerra Department of History Yale University [email protected] s the fiftieth anniversary of the Cuban Revolution of 1959 Adraws near, new assessments of its origins, course, and legacies are clearly needed. -

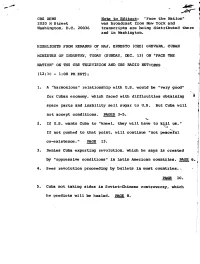

JI 7 , ~~ ~ CBS NEWS Note to Editors: Ilface the Nationll L 2020 M S·Treet Was Broadcast from New Yqrk and Washington, D.C

~ ..JI 7 , ~~ ~ CBS NEWS Note to Editors: IlFace the Nationll l 2020 M S·treet was broadcast from New Yqrk and Washington, D.C. 20036 transcripts are being distributed there and in washington. HIGHLIGHTS FROM REMARKS OF MAJ. ERNESTO (CHE) GUEVARA, CUBAN MINISTER OF INDUSTRY, TODAY (SUNDAY, mc. 13) ON uFACE THE NATION lI ON THE CES TELEVISION AND CBS RADIO NET'[(ORKS (12:30 - 1:00 PM EST): 1. A "harmonious" re1ationship with U.S. wou1d be " very góod" for Cuban economy, which faced with difficu1ties obtainingl spare parts and inabi1ity se11 sugar to U.S. But Cuba wi11 not accept conditions. PAGES 3-5. " 2. If U.S. wants Cuba to IIknee1, they wi11 have to jsi.l1 us. 11 ~ ·~0 • If not pushed to that point, wi11 continue II not peacefu1 co-existence. fI ~ 13. 3. Denies Cuba exporti'ng revo1ution, which he says 1s created by lIoppressive conditions" in Latin American countries. ~ 6. 4. Sees revo1ution proceeding by bu11ets in most countr1es.~ ~ 10. 5. Cuba not taking sides in Soviet-Ch1nese controversy, which he predicts wi11 be hea1ed. ~ 8. ------.¡ 1 Mills CBS NEWS Mills 2020 M Street Washington, D.C. 20036 11 FACE THE NATrON" as broadcas t ove r the CBS Television Network and the CBS Radio Network Sunday, December 13, 1964 -- 12:30 - 1:00 PM EST GUEST: MAJOR ERNESTO GUEVARA Minister of Industry of Cuba , NEWS CORRESPONDENTS: Paul Niven CBS News Tad Szulc New York Times Richard C. llottelet CBS News PRODUCERS: Prentiss Cl1ilds Ellen Wadley DIRECTOR: Robert Vitarelli 2 MR. NlVEN: Major Guevara, in your speech to tIJe General Assembly the day before yesterday, you accused the United States of ilelping Cuba t s neighbors prepare new aggression against her.