Character and Culture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Imaginative Tension in Henry David Thoreau's Political Thought

THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY OF AMERICA Arcadian Exile: The Imaginative Tension in Henry David Thoreau’s Political Thought A DISSERTATION Submitted to the Faculty of the Department of Politics School of Arts and Sciences of the Catholic University of America In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree Doctor of Philosophy © Copyright All Rights Reserved By Joshua James Bowman Washington, D.C. 2016 Arcadian Exile: The Imaginative Tension in Henry David Thoreau’s Political Thought Joshua James Bowman, Ph.D. Director: Claes G. Ryn, Ph.D. Henry David Thoreau‘s writings have achieved a unique status in the history of American literature. His ideas influenced the likes of Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr., and play a significant role in American environmentalism. Despite this influence his larger political vision is often used for purposes he knew nothing about or could not have anticipated. The purpose of this dissertation is to analyze Thoreau’s work and legacy by elucidating a key tension within Thoreau's imagination. Instead of placing Thoreau in a pre-conceived category or worldview, the focus on imagination allows a more incisive reflection on moral and spiritual questions and makes possible a deeper investigation of Thoreau’s sense of reality. Drawing primarily on the work of Claes Ryn, imagination is here conceived as a form of consciousness that is creative and constitutive of our most basic sense of reality. The imagination both shapes and is shaped by will/desire and is capable of a broad and qualitatively diverse range of intuition which varies depending on one’s orientation of will. -

FREE Shipping Use Promo Code WCM21 When Ordering

HSJ2021B We’ve Got a Sticker for That™ ® Powered by MediBadge®, Inc. Win them over with Stickers, Bandages, Toys and More! SAVE Now! FREE Shipping Use Promo Code WCM21 when ordering. Expires 12-31-21. See back for details. Stylish Flat size: 5 7/8” x 33/4” 2 designs per pack # 5915 Rainbows & Butterflies Kids Face Masks 6 per pack $13.99 # VLM01 for Kids! Flat size: 5 7/8” x 33/4” Flu Shot 2 designs per pack Value Roll Stickers™ • Fits kids ages 5-12 100 stickers per roll $3.00 • Latex Free • Comfortable earloop design 6 designs per unit. Sticker size 15/8” (Designs shown reduced.) • 3 layer, non-woven polypropylene (NWPP) # 5913 material with activated carbon layer Sports & Building Blocks • CE certified, helps reduce the risk against Kids Face Masks floating droplets as a daily protective 6 per pack $13.99 and decorative mask • NOT for medical use Flat size: 5 7/8” x 33/4” • Disposable 2 designs per pack Face Mask package must be unopened to be eligible for return. # VLM01X Flu Shot MEGA Roll Value Stickers™ # 5914 Leopard Camo & Rainbow Skin 1,000 stickers per roll $24.95 Kids Face Masks Value Line Stickers cannot be combined with our Mix & Match Stickers for Quantity Pricing. Value Line Stickers available on rolls only. 6 per pack $13.99 We know you put the “care” in # 5443 Travel Size Sanell® Hand Sanitizer 30 .5 fl. oz. bottles per canister $32.95 HEALTH CARE! Cover ‘em, Remind ‘em, Reward ‘em! 2" 6 designs per unit. -

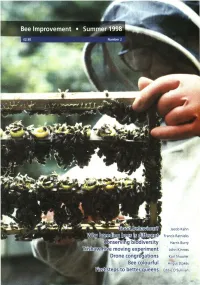

Dlifarariit Conserving Biodiversity Hive Moving Experiment Drone

cd; ,•„1.4:" Jacob Kahn dlifarariit Francis Ratnieks Conserving biodiversity Harris Burry hive moving experiment John Kinross Drone congregations Karl Showier Bee colourful Angus Stokes steps to better queens Eddie O'Sullivan Ed itoria Big improvement congregations exist and that in the hive, everything parameters for Apis m.m. There was an encouraging queens will fly great perfect ... not this year, then it is unusual for other reception for first issue of distances to be mated at never? August was good at physical characteristics to 'Bee Improvement' congregations. the start and the heather be 'non-native'. magazine (BIM). It was looks a picture, what will the A wing morphometry regarded by some as Volunteers remainder of the season on sample which appears to be Editorial progress and a step forward Dr Francis Ratnieks has the moors bring us? 100% Apis m.m. is very for BIBBA and its aims. volunteered to be a unlikely to have any bees New BIBBA members scientific advisor for 'Bee NZ bee packages with yellow (abdominal) Good behaviour joined as a result of seeing Improvement' starting with Yet again, MAFF propose to stripes or spots, for Jacob Kahn the magazine. Show this the next issue. He has wide allow the importation of example. Consequently, second issue to your ranging academic and bees from New Zealand. those bee breeders who use Why breeding bees is different beekeeping acquaintances practical experience of bee Why? - because only wing morphometry as Dr Francis Ratnieks as a way of increasing breeding in several beekeepers who have lost an identifier for Apis m.m. -

Justice League: Origins

JUSTICE LEAGUE: ORIGINS Written by Chad Handley [email protected] EXT. PARK - DAY An idyllic American park from our Rockwellian past. A pick- up truck pulls up onto a nearby gravel lot. INT. PICK-UP TRUCK - DAY MARTHA KENT (30s) stalls the engine. Her young son, CLARK, (7) apprehensively peeks out at the park from just under the window. MARTHA KENT Go on, Clark. Scoot. CLARK Can’t I go with you? MARTHA KENT No, you may not. A woman is entitled to shop on her own once in a blue moon. And it’s high time you made friends your own age. Clark watches a group of bigger, rowdier boys play baseball on a diamond in the park. CLARK They won’t like me. MARTHA KENT How will you know unless you try? Go on. I’ll be back before you know it. EXT. PARK - BASEBALL DIAMOND - MOMENTS LATER Clark watches the other kids play from afar - too scared to approach. He is about to give up when a fly ball plops on the ground at his feet. He stares at it, unsure of what to do. BIG KID 1 (yelling) Yo, kid. Little help? Clark picks up the ball. Unsure he can throw the distance, he hesitates. Rolls the ball over instead. It stops halfway to Big Kid 1, who rolls his eyes, runs over and picks it up. 2. BIG KID 1 (CONT’D) Nice throw. The other kids laugh at him. Humiliated, Clark puts his hands in his pockets and walks away. Big Kid 2 advances on Big Kid 1; takes the ball away from him. -

Magazines V17N9.Qxd

Oct10 Toys:section 9/14/2010 1:54 PM Page 358 ANIMATION TA ROBOT CHICKEN ACTION FIGURES Action figures find new life as players in frenetic sketch-comedy vignettes that skewer TV, movies, music and celebrity as old-school stop-motion animation and fast-paced satire combine in Robot Chicken, an eclectic show created by Seth Green and Matt Senreich. Fans of the [adult swim] series will want to collect these action figures based FUTURAMA SERIES 9 ACTION FIGURES on the series, including Action Robot (6” tall), Candy Bear (5” tall), and the Mad Sci- Good news, everyone! Matt Groening’s Futurama has returned to television screens every- entist with Robot Chicken (6” and 3 1/2” tall respectively). Or they can 10” tall Elec- where, and Toynami celebrates the return of our favorite 31st-century heroes with two all- tronic Robot Chicken for more mechanical mayhem! Scheduled to ship in December new figures from the cult favorite series! Choose from URL, the robotic policeman, or 2010. (6848) (C: 1-1-3) NOTE: Available only in the United States, Canada, and U.S. Wooden Bender, from the 4th season episode “Obsoletely Fabulous.” Each figure stands Territories. 6” tall. Window box packaging. (4522/5010) (C: 1-1-3) NOTE: Available only in the ACTION FIGURES (14000)—Figure .................................................................PI United States, Canada, and U.S. Territories. 10” ELECTRONIC ROBOT CHICKEN (14010)—Figure .......................................PI Figure ..........................................................................................................$13.99 -

Shepard - Coming Home to the Pleistocene.Pdf

Coming Home to the Pleistocene Paul Shepard Edited by Florence R. Shepard ISLAND PRESS / Shearwater Books Washington, D.C. • Covelo, California A Shearwater Book published by Island Press Copyright © 1998 Florence Shepard All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the publisher: Island Press, 1718 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 300, Washington, DC 20009. Shearwater Books is a trademark of The Center for Resource Economics. LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA Shepard, Paul, 1925–1996 Coming home to the Pleistocene / Paul Shepard ; edited by Florence R. Shepard. p. cm. “A Shearwater book”— Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1–55963–589–4. — ISBN 1–55963–590–8 1. Hunting and gathering societies. 2. Sociobiology. 3. Nature and nurture. I. Shepard, Florence R. II. Title. GN388.S5 1998 98-8074 306.3’64—dc21 CIP Printed on recycled, acid-free paper Manufactured in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Contents Preface ix Introduction 1 I. The Relevance of the Past 7 Our Pleistocene ancestors and contemporary hunter/gatherers cannot be under- stood in a historical context that, as a chronicle of linear events, has distorted the meaning of the “savage” in us. II. Getting a Genome 19 Being human means having evolved—especially with respect to a special past in open country, where the basic features that make us human came into being. Coming down out of the trees, standing on our own two feet, freed our hands and brought a perceptual vision never before seen on the planet. -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Art and Life in America by Oliver W. Larkin Harvard Art Museums / Fogg Museum | Bush-Reisinger Museum | Arthur M

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Art and Life in America by Oliver W. Larkin Harvard Art Museums / Fogg Museum | Bush-Reisinger Museum | Arthur M. Sackler Museum. In this allegorical portrait, America is personified as a white marble goddess. Dressed in classical attire and crowned with thirteen stars representing the original thirteen colonies, the figure gives form to associations Americans drew between their democracy and the ancient Greek and Roman republics. Like most nineteenth-century American marble sculptures, America is the product of many hands. Powers, who worked in Florence, modeled the bust in plaster and then commissioned a team of Italian carvers to transform his model into a full-scale work. Nathaniel Hawthorne, who visited Powers’s studio in 1858, captured this division of labor with some irony in his novel The Marble Faun: “The sculptor has but to present these men with a plaster cast . and, in due time, without the necessity of his touching the work, he will see before him the statue that is to make him renowned.” Identification and Creation Object Number 1958.180 People Hiram Powers, American (Woodstock, NY 1805 - 1873 Florence, Italy) Title America Other Titles Former Title: Liberty Classification Sculpture Work Type sculpture Date 1854 Places Creation Place: North America, United States Culture American Persistent Link https://hvrd.art/o/228516 Location Level 2, Room 2100, European and American Art, 17th–19th century, Centuries of Tradition, Changing Times: Art for an Uncertain Age. Signed: on back: H. Powers Sculp. Henry T. Tuckerman, Book of the Artists: American Artist Life, Comprising Biographical and Critical Sketches of American Artists, Preceded by an Historical Account of the Rise and Progress of Art in America , Putnam (New York, NY, 1867), p. -

Frankels & Donegal Racing Partner on Keen Ice In

WEDNESDAY, DECEMBER 28, 2016 FRANKELS & DONEGAL PEGASUS WORLD CUP MAY MOVE TO SANTA ANITA By Bill Finley RACING PARTNER ON Already contemplating changes that could make future runnings of the $12-million GI Pegasus World Cup bigger and KEEN ICE IN PEGASUS better, the Stronach Group is seriously considering moving the race to Santa Anita for the 2018 edition. ANothing has been confirmed, but, yes, there have been internal discussions about going to Santa Anita next year,@ said Mike Rogers, the Stronach Group=s President of Racing. AThe ultimate decision will be made by Frank and Belinda Stronach. While a beautiful facility, Gulfstream is a small facility and that has created challenges for us, challenges we are trying to work through. Santa Anita is a much bigger facility and many big events have been pulled off there.@ Cont. p3 IN TDN EUROPE TODAY OSCIETRA CROSS-ENTERED DOWN UNDER Oscietra (Aus) (Exceed And Excel {Aus}), the first foal from the undefeated Australian superstar Black Caviar (Aus) (Bel Esprit Keen Ice | Sarah K. Andrew {Aus}), has been entered in a pair of 1000-metre juvenile races at Moonee Valley Dec. 31 and Flemington on New Year’s Day. Click GI Pegasus World Cup gate owners Jerry and Ronnie Frankel or tap here to go straight to TDN Europe. will partner with Jerry Crawford=s Donegal Racing to race 2015 GI Travers S. hero Keen Ice (Curlin) in the inaugural running of the $12-million test at Gulfstream Jan. 28, Donegal Racing announced Tuesday. Trained by Todd Pletcher, the hulking bay ran third behind likely Pegasus favorites Arrogate (Unbridled=s Song) and California Chrome (Lucky Pulpit) in the GI Breeders= Cup Classic at Santa Anita Nov. -

Personal, Societal, and Ecological Values of Wilderness: Sixth World Wilderness Congress Proceedings on Research, Management, and Allocation, Vol

United States Department Personal, Societal, and of Agriculture Forest Service Ecological Values of Wilderness: Rocky Mountain Research Station Sixth World Wilderness Proceedings RMRS-P-14 Congress Proceedings on July 2000 Research, Management, and Allocation, Volume II Abstract Watson, Alan E.; Aplet, Greg H.; Hendee, John C., comps. 2000. Personal, societal, and ecological values of wilderness: Sixth World Wilderness Congress proceedings on research, management, and allocation, vol. II; 1998 October 24-29; Bangalore, India. Proc. RMRS-P-14. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 248 p. The papers contained in Volume II of these Proceedings represent a combination of papers originally scheduled for the delayed 1997 meeting of the World Wilderness Congress and those submitted in response to a second call for papers when the Congress was rescheduled for October 24-29, 1998, in Bangalore, India. Just as in Volume I, the papers are divided into seven topic areas: protected area systems: challenges, solutions, and changes; understanding and protecting biodiversity; human values and meanings of wilderness; wilderness for personal growth; understanding threats and services related to wilderness resources; the future of wilderness: challenges of planning, management, training, and research; and international cooperation in wilderness protection. Keywords: biodiversity, protected areas, tourism, economics, recreation, wildlife, international cooperation The Compilers Alan E. Watson is a Research Social Scientist, USDA Forest Service, Aldo Leopold Wilderness Research Institute, and Executive Editor for Science, the International Journal of Wilderness. The Aldo Leopold Wilderness Research Institute is an interagency (Forest Service, Bureau of Land Management, National Park Service, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, U.S. -

PULITZER PRIZE WINNERS in LETTERS © by Larry James

PULITZER PRIZE WINNERS IN LETTERS © by Larry James Gianakos Fiction 1917 no award *1918 Ernest Poole, His Family (Macmillan Co.; 320 pgs.; bound in blue cloth boards, gilt stamped on front cover and spine; full [embracing front panel, spine, and back panel] jacket illustration depicting New York City buildings by E. C.Caswell); published May 16, 1917; $1.50; three copies, two with the stunning dust jacket, now almost exotic in its rarity, with the front flap reading: “Just as THE HARBOR was the story of a constantly changing life out upon the fringe of the city, along its wharves, among its ships, so the story of Roger Gale’s family pictures the growth of a generation out of the embers of the old in the ceaselessly changing heart of New York. How Roger’s three daughters grew into the maturity of their several lives, each one so different, Mr. Poole tells with strong and compelling beauty, touching with deep, whole-hearted conviction some of the most vital problems of our modern way of living!the home, motherhood, children, the school; all of them seen through the realization, which Roger’s dying wife made clear to him, that whatever life may bring, ‘we will live on in our children’s lives.’ The old Gale house down-town is a little fragment of a past generation existing somehow beneath the towering apartments and office-buildings of the altered city. Roger will be remembered when other figures in modern literature have been forgotten, gazing out of his window at the lights of some near-by dwelling lifting high above his home, thinking -

Heroclix Campaign

HeroClix Campaign DC Teams and Members Core Members Unlock Level A Unlock Level B Unlock Level C Unless otherwise noted, team abilities are be purchased according to the Core Rules. For unlock levels listing a Team Build (TB) requisite, this can be new members or figure upgrades. VPS points are not used for team unlocks, only TB points. Arkham Inmates Villain TA Batman Enemy Team Ability (from the PAC). SR Criminals are Mooks. A 450 TB points of Arkham Inmates on the team. B 600 TB points of Arkham Inmates on the team. Anarky, Bane, Black Mask, Blockbuster, Clayface, Clayface III, Deadshot, Dr Destiny, Firefly, Cheetah, Criminals, Ambush Bug. Jean Floronic Man, Harlequin, Hush, Joker, Killer Croc, Mad Hatter, Mr Freeze, Penguin, Poison Ivy, Dr Arkham, The Key, Loring, Kobra, Professor Ivo, Ra’s Al Ghul, Riddler, Scarecrow, Solomon Grundy, Two‐Face, Ventriloquist. Man‐Bat. Psycho‐Pirate. Batman Enemy See Arkham Inmates, Gotham Underground Villain Batman Family Hero TA The Batman Ally Team Ability (from the PAC). SR Bat Sentry may purchased in Multiples, but it is not a Mook. SR For Batgirl to upgrade to Oracle, she must be KOd by an opposing figure. Environment or pushing do not count. If any version of Joker for KOs Level 1 Batgirl, the player controlling Joker receives 5 extra points. A 500 TB points of Batman members on the team. B 650 TB points of Batman members on the team. Azrael, Batgirl (Gordon), Batgirl (Cain), Batman, Batwoman, Black Catwoman, Commissioner Gordon, Alfred, Anarky, Batman Canary, Catgirl, Green Arrow (Queen), Huntress, Nightwing, Question, Katana, Man‐Bat, Red Hood, Lady Beyond, Lucius Fox, Robin (Tim), Spoiler, Talia. -

Pulitzer Prize Winners and Finalists

WINNERS AND FINALISTS 1917 TO PRESENT TABLE OF CONTENTS Excerpts from the Plan of Award ..............................................................2 PULITZER PRIZES IN JOURNALISM Public Service ...........................................................................................6 Reporting ...............................................................................................24 Local Reporting .....................................................................................27 Local Reporting, Edition Time ..............................................................32 Local General or Spot News Reporting ..................................................33 General News Reporting ........................................................................36 Spot News Reporting ............................................................................38 Breaking News Reporting .....................................................................39 Local Reporting, No Edition Time .......................................................45 Local Investigative or Specialized Reporting .........................................47 Investigative Reporting ..........................................................................50 Explanatory Journalism .........................................................................61 Explanatory Reporting ...........................................................................64 Specialized Reporting .............................................................................70