The Neo Geo AES and the Object a of Videogame History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Neo-Geo Hardware Specification

Confidential 0future is Neo-Geo Hardware Specification SNK Neo-Geo Hardware Specification Table of Contents Neo-Geo Specification ............................. Hardware .1 Special Features of the "3D-LINE SPRITE" ................ Hardware .3 Specification of Each Function ........................ Hardware .4 FIX .................................... Hardware .4 Background ................................ Hardware .4 3D-Line Sprite .............................. Hardware .4 Interrupts ...................................... Hardware .5 Interrupt-1 ................................ Hardware .5 Interrupt-2 ................................ Hardware .5 Access to Line Sprite Controller (LSPC) .................. Hardware .6 Address Map of the 68000 ........................... Hardware .8 Address Map of the 280 ............................ Hardware .10 I/O Map of the 280 ............................... Hardware .10 # Sound Function ................................. Hardware .10 Notes ....................................... Hardware .10 3D Line Sprite .................................. Hardware .12 Vertical and Horizontal Positions .................. Hardware .13 Example of the Number of Active Characters (ACT). Vertical Reduction (BIGV). and Horizontal Reduction (BIGH) Hardware .14 Address Mapping of the FIX Area (VRAM) (In the NTSC Mode)Hardware .15 Address Mapping of the FIX Area (VRAM) (In the PAL Mode) Hardware .16 Address Example of the 3D-Line Sprite .............. Hardware .17 Address Mapping of the 3D-Line Sprite .............. Hardware -

The Indigenous Shôjo: Transmedia Representations of Ainu Femininity In

Journal of Anime and Manga Studies Volume 1 The Indigenous Shôjo: Transmedia Representations of Ainu Femininity in Japan’s Samurai Spirits, 1993–2019 Christina Spiker Volume 1, Pages 138-168 Abstract: Little scholarly attention has been given to the visual representations of the Ainu people in popular culture, even though media images have a significant role in forging stereotypes of indigeneity. This article investigates the role of representation in creating an accessible version of indigenous culture repackaged for Japanese audiences. Before the recent mainstream success of manga/anime Golden Kamuy (2014–), two female heroines from the arcade fighting game Samurai Spirits (Samurai supirittsu)— Nakoruru and her sister Rimururu—formed a dominant expression of Ainu identity in visual culture beginning in the mid-1990s. Working through the in-game representation of Nakoruru in addition to her larger mediation in the anime media mix, this article explores the tensions embodied in her character. While Nakoruru is framed as indigenous, her body is simultaneously represented in the visual language of the Japanese shôjo, or “young girl.” This duality to her fetishized image cannot be reconciled and is critical to creating a version of indigenous femininity that Japanese audiences could easily consume. This paper historicizes various representations of indigenous Otherness against the backdrop of Japanese racism and indigenous activism in the late 1990s and early 2000s by analyzing Nakoruru’s official representation in the game franchise, including her appearance in a 2001 OVA, alongside fan interpretations of these characters in self-published comics (dôjinshi) criticized by Ainu scholar Chupuchisekor. Keywords: Ainu, indigenous studies, shôjo, gender, arcade gaming, stereotypes Author Bio: Christina M. -

Comparatif Line up Neogeo Mini.Xlsx

Neo Geo Mini Samurai Showdown (40 jeux) Neo Geo Mini International (40 jeux) Neo Geo Mini Christmas (48 jeux) Neo Geo Asiatique (40 jeux) Agressor of Dark Combat 3 Count Bout Agressors of Dark Combat Aggressors of Dark Kombat Alpha Mission 2 Art of Fighting Alpha Mission 2 Alpha Mission II Art of Fighting Blazing Star Art of Fighting Art of Fighting Blazing Star Blue’s Journey Blazing Star Blazing Star Blue’s Journey Crossed Swords Blue’s Journey Burning Fight Burning Fight Fatal Fury Special Burning Fight Cyber-Lip Cyber Lip Foot Ball Frenzy Cyber Lip Fatal Fury Special Fatal Fury Garou : Mark of the Wolves Fatal Fury Garou : Mark of the Wolves Fatal Fury 2 Ghost Pilots Fatal Fury 2 King of Monsters 2 Garou : Mark of the Wolves King of the Monsters Fatal Fury 3 Kizuna Encounter : Super Tag Battle King of the Monsters 2 King of the Monsters 2 Garou : Mark of the Wolves Metal Slug Kizuna Encounter : Super Tag Battle Kizuna Encounter : Super Tag Battle King of the Monsters Metal Slug 2 League Bowling Last Resort King of the Monsters 2 Metal Slug 3 Magician Lord Magician Lord Kizuna Encounter : Super Tag Battle Ninja Commando Metal Slug Metal Slug League Bowling Ninja Master's : Haou Ninpou Chou Metal Slug 2 Metal Slug 2 Magician Lord Puzzled Metal Slug 3 Metal Slug 3 Metal Slug Real Bout Fatal Fury 2 : The Newcomers Ninja Combat Metal Slug 4 Metal Slug 2 Real Bout : Fatal Fury Ninja Master's : Haou Ninpou Chou Metal Slug 5 Metal Slug 3 Samurai Shodown II Real Bout : Fatal Fury 2 Metal Slug X Metal Slug 4 Samurai Shodown IV : Amakusa’s Revenge -

Fighting Games, Performativity, and Social Game Play a Dissertation

The Art of War: Fighting Games, Performativity, and Social Game Play A dissertation presented to the faculty of the Scripps College of Communication of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Todd L. Harper November 2010 © 2010 Todd L. Harper. All Rights Reserved. This dissertation titled The Art of War: Fighting Games, Performativity, and Social Game Play by TODD L. HARPER has been approved for the School of Media Arts and Studies and the Scripps College of Communication by Mia L. Consalvo Associate Professor of Media Arts and Studies Gregory J. Shepherd Dean, Scripps College of Communication ii ABSTRACT HARPER, TODD L., Ph.D., November 2010, Mass Communications The Art of War: Fighting Games, Performativity, and Social Game Play (244 pp.) Director of Dissertation: Mia L. Consalvo This dissertation draws on feminist theory – specifically, performance and performativity – to explore how digital game players construct the game experience and social play. Scholarship in game studies has established the formal aspects of a game as being a combination of its rules and the fiction or narrative that contextualizes those rules. The question remains, how do the ways people play games influence what makes up a game, and how those players understand themselves as players and as social actors through the gaming experience? Taking a qualitative approach, this study explored players of fighting games: competitive games of one-on-one combat. Specifically, it combined observations at the Evolution fighting game tournament in July, 2009 and in-depth interviews with fighting game enthusiasts. In addition, three groups of college students with varying histories and experiences with games were observed playing both competitive and cooperative games together. -

Dual-Forward-Focus

Scroll Back The Theory and Practice of Cameras in Side-Scrollers Itay Keren Untame [email protected] @itayke Scrolling Big World, Small Screen Scrolling: Neural Background Fovea centralis High cone density Sharp, hi-res central vision Parafovea Lower cone density Perifovea Lowest density, Compressed patterns. Optimized for quick pattern changes: shape, acceleration, direction Fovea centralis High cone density Sharp, hi-res central vision Parafovea Lower cone density Perifovea Lowest density, Compressed patterns. Optimized for quick pattern changes: shape, acceleration, direction Thalamus Relay sensory signals to the cerebral cortex (e.g. vision, motor) Amygdala Emotional reactions of fear and anxiety, memory regulation and conditioning "fight-or-flight" regulation Familiar visual patterns as well as pattern changes may cause anxiety unless regulated Vestibular System Balance, Spatial Orientation Vestibulo-Ocular Reflex Natural image stabilizer Conflicting sensory signals (Visual vs. Vestibular) may lead to discomfort and nausea* * much worse in 3D (especially VR), but still effective in 2D Scrolling with Attention, Interaction and Comfort Attention: Use the camera to provide sufficient game info and feedback Interaction: Make background changes predictable, tightly bound to controls Comfort: Ease and contextualize background changes Attention The Elements of Scrolling Interaction Comfort Scrolling Nostalgia Rally-X © 1980 Namco Scramble © 1981 Jump Bug © 1981 Defender © 1981 Konami Hoei/Coreland (Alpha Denshi) Williams Electronics Vanguard -

Openbsd Gaming Resource

OPENBSD GAMING RESOURCE A continually updated resource for playing video games on OpenBSD. Mr. Satterly Updated August 7, 2021 P11U17A3B8 III Title: OpenBSD Gaming Resource Author: Mr. Satterly Publisher: Mr. Satterly Date: Updated August 7, 2021 Copyright: Creative Commons Zero 1.0 Universal Email: [email protected] Website: https://MrSatterly.com/ Contents 1 Introduction1 2 Ways to play the games2 2.1 Base system........................ 2 2.2 Ports/Editors........................ 3 2.3 Ports/Emulators...................... 3 Arcade emulation..................... 4 Computer emulation................... 4 Game console emulation................. 4 Operating system emulation .............. 7 2.4 Ports/Games........................ 8 Game engines....................... 8 Interactive fiction..................... 9 2.5 Ports/Math......................... 10 2.6 Ports/Net.......................... 10 2.7 Ports/Shells ........................ 12 2.8 Ports/WWW ........................ 12 3 Notable games 14 3.1 Free games ........................ 14 A-I.............................. 14 J-R.............................. 22 S-Z.............................. 26 3.2 Non-free games...................... 31 4 Getting the games 33 4.1 Games............................ 33 5 Former ways to play games 37 6 What next? 38 Appendices 39 A Clones, models, and variants 39 Index 51 IV 1 Introduction I use this document to help organize my thoughts, files, and links on how to play games on OpenBSD. It helps me to remember what I have gone through while finding new games. The biggest reason to read or at least skim this document is because how can you search for something you do not know exists? I will show you ways to play games, what free and non-free games are available, and give links to help you get started on downloading them. -

161 in 1 Neogeo Multigame Cartridge

PCBs : 161 in 1 NeoGeo Multigame Cartridge 161 in 1 NeoGeo Multigame Cartridge Rating: Not Rated Yet Price: Sales price: $99.95 Discount: Ask a question about this product This amazing cart combines 161 of the best Neo Geo games onto a single Neo Geo cartridge. The cartridge uses a built-in OSD (On Screen Display) to first graphically navigate to the game you wish to play. Once finished playing, simply hold down Player 1 START button for 5 seconds to immediately return to the OSD game selection screen again. Description Game List: 1 SNK VS CAPCOM + 2 SNK VS CAPCOM RMX 3 SVC SUPER PLUS 4 KOF 94 5 KOF 94 + 6 KOF 95 7 KOF 95 + 8 KOF 96 9 KOF 96 + 10 KOF 96 EVO 11 KOF 97 12 KOF 97 2003 13 KOF 97 REMIX 14 KOF 97 PLUS 15 KING OF GLADIATOR 16 KOG PLUS 17 KOF 98 18 KOF 98 + 19 KOF 98 ULTIMATE 20 KOF 98 OROCHI 21 KOF 99 22 KOF 99 + 23 KOF 99 CN 24 KOF 2001 25 KOF 2001 PLUS 26 C.T.H.D 27 C.T.H.D SUPER PLUS 28 KOF 2002 29 KOF 2002 MAGIC 30 KOF 2002 MAGIC 2 31 KOF 2002 CN 32 KOF 2002 OROCHI 33 KOF 2002 LUAN 34 KOF 2002 SUPER 35 KOF 2002 SUPER 2 36 KOF 2003 37 KOF 2004 SE PLUS 38 KOF 2004 SE 39 KOF 2004 SMP 40 KOF 10TH 41 KOF 05 UNIQUE 42 KOF 05 UNIQUE 2 43 KOF 10TH EXTRA + 44 RAGE OF DRAGONS 45 RAGE OF DRAGONS + 46 STRIKERS 1945 + 47 STRIKERS 1945 + + 48 AERO FIGHTERS 2 49 AERO FIGHTERS 3 50 METAL SLUG 51 METAL SLUG + 52 METAL SLUG 2 53 METAL SLUG 2 + 54 METAL SLUG 3 55 METAL SLUG 3 + 56 METAL SLUG 4 57 METAL SLUG 4 + 58 METAL SLUG X 59 METAL SLUG X + 60 METAL SLUG 6 61 METAL SLUG 6 + 62 SUPER SIDEKICKS 2 63 SUPER SIDEKICKS 3 64 ULTIMATE 11 65 NEO-GEO -

Nintendo Wii

Nintendo Wii Last Updated on September 24, 2021 Title Publisher Qty Box Man Comments Another Code: R - Kioku no Tobira Nintendo Arc Rise Fantasia Marvelous Entertainment Bio Hazard Capcom Bio Hazard: Best Price! Capcom Bio Hazard: Best Price! Reprint Capcom Bio Hazard 4: Wii Edition Capcom Bio Hazard 4: Wii Edition: Best Price! Capcom Bio Hazard 4: Wii Edition: Best Price! Reprint Capcom Bio Hazard Chronicles Value Pack Capcom Bio Hazard Zero Capcom Bio Hazard Zero: Best Price! Capcom Bio Hazard Zero: Best Price! Reprint Capcom Bio Hazard: The Darkside Chronicles Capcom Bio Hazard: The Darkside Chronicles: Collector's Package Capcom Bio Hazard: The Darkside Chronicles: Best Price! Capcom Bio Hazard: The Umbrella Chronicles Capcom Bio Hazard: The Umbrella Chronicles: Wii Zapper Bundle Capcom Bio Hazard: The Umbrella Chronicles: Best Price! Capcom Bio Hazard: The Umbrella Chronicles: Best Price! Reprint Capcom Biohazard: Umbrella Chronicals Capcom Bleach: Versus Crusade Sega Bomberman Hudson Soft Bomberman: Hudson the Best Hudson Soft Captain Rainbow Nintendo Chibi-Robo! (Wii de Asobu) Nintendo Dairantou Smash Brothers X Nintendo Deca Sporta 3 Hudson Disaster: Day of Crisis Nintendo Donkey Kong Returns Nintendo Donkey Kong Taru Jet Race Nintendo Dragon Ball Z: Sparking! Neo Bandai Namco Games Dragon Quest 25th Anniversary Square Enix Dragon Quest Monsters: Battle Road Victory Square Enix Dragon Quest Sword: Kamen no Joou to Kagami no Tou Square Enix Dragon Quest X: Mezameshi Itsutsu no Shuzoku Online Square Enix Earth Seeker Enterbrain -

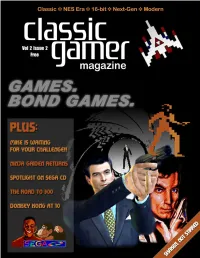

Cgm V2n2.Pdf

Volume 2, Issue 2 July 2004 Table of Contents 8 24 Reset 4 Communist Letters From Space 5 News Roundup 7 Below the Radar 8 The Road to 300 9 Homebrew Reviews 11 13 MAMEusements: Penguin Kun Wars 12 26 Just for QIX: Double Dragon 13 Professor NES 15 Classic Sports Report 16 Classic Advertisement: Agent USA 18 Classic Advertisement: Metal Gear 19 Welcome to the Next Level 20 Donkey Kong Game Boy: Ten Years Later 21 Bitsmack 21 Classic Import: Pulseman 22 21 34 Music Reviews: Sonic Boom & Smashing Live 23 On the Road to Pinball Pete’s 24 Feature: Games. Bond Games. 26 Spy Games 32 Classic Advertisement: Mafat Conspiracy 35 Ninja Gaiden for Xbox Review 36 Two Screens Are Better Than One? 38 Wario Ware, Inc. for GameCube Review 39 23 43 Karaoke Revolution for PS2 Review 41 Age of Mythology for PC Review 43 “An Inside Joke” 44 Deep Thaw: “Moortified” 46 46 Volume 2, Issue 2 July 2004 Editor-in-Chief Chris Cavanaugh [email protected] Managing Editors Scott Marriott [email protected] here were two times a year a kid could always tures a firsthand account of a meeting held at look forward to: Christmas and the last day of an arcade in Ann Arbor, Michigan and the Skyler Miller school. If you played video games, these days writer's initial apprehension of attending. [email protected] T held special significance since you could usu- Also in this issue you may notice our arti- ally count on getting new games for Christmas, cles take a slight shift to the right in the gaming Writers and Contributors while the last day of school meant three uninter- timeline. -

SNK 40Th Anniversary Collection

SNK 40th Anniversary Collection 2018 marks the 40th anniversary of legendary studio SNK! To celebrate this extraordinary milestone, a variety of classic arcade games from SNK’s golden age are coming back together in one anthology on Nintendo Switch. SNK 40th ANNIVERSARY COLLECTION is packed full of retro games and a treasure trove of features! • Alpha Mission (Console/Arcade), Athena (Console/Arcade), Crystalis Street Date Tue 11/13/18 (Console), Ikari Warriors (Console/Arcade), Ikari Warriors II: Victory Road (Console/Arcade), Ikari Warriors III: The Rescue System Switch (Console/Arcade), Guerrilla War (Console/Arcade), P.O.W. (Console/Arcade), Prehistoric Isle (Arcade), Psycho Soldier (Arcade), Genre Retro/Compilation Street Smart (Arcade), TNK III (Console/Arcade), Vanguard (Arcade), and more to be announced. ESRB T • Ten games will be made available post-launch. The first five Developer SNK Corporation announced are: Chopper 1 , Fantasy , Munch Mobile , Sasuke vs Commander , and Time Soldiers . Publisher NIS America, Inc. • Take a piece of SNK history with you wherever you go on Nintendo Switch. Choose from over a dozen titles and experience an intense MSRP $39.99 US / $54.99 CA blast from the past! • The convenience and improvements of modern gaming are all in the UPC 8-10023-03148-2 collection! Rewind and save at any time while you’re playing, enjoy updated graphics at 1080p resolution, and experience redesigned SKU SN-03148-2 control schemes for a modern feel! # of Players Single • An extensive history of SNK and its games await in the Museum Mode. Explore the legacy of one of Japan’s leading developers with Packaging English/French high definition artwork and original promotional assets! Languages In-game Text English In-game Voice N/A Official Game Site www.SNK40th.com Updated: 09/19/18 Get marketing assets at http://atlus.com/sales/ Published by Distributed exclusively by ©SNK CORPORATION ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. -

![Moves] - NEO Encyclopedia 1 / 4](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0236/moves-neo-encyclopedia-1-4-1380236.webp)

Moves] - NEO Encyclopedia 1 / 4

Art of Fighting 3 [moves] - NEO Encyclopedia 1 / 4 The Unofficial SNK Neo Geo Games Encyclopedia of Moves & Codes http://sindoni.altervista.org/neoencyclopedia/ [moves] Robert Garcia Ryo Sakazaki Rody Birts Kasumi Todoh Koh-San Wang Lenny Creston Carman Cole Jin Fu-Ha General Moves Punch Kick Strong Attack Taunt hold Recharge Spirit jump Short jump Back step Front step Mid level strike Rush Punch / Rush Kick Throw Sabaki Motion Robert Garcia Command Attacks Burning Knuckle mid-level kick Double Middle Back Blow Double Middle Raging Kick Triple Kick crouch Jumping Heel Throw Pursuit Shoulder Throw Yankee Kick Special Moves Ryuu Geki Ken RyuuGa Genei Kyaku HienShippuKyaku jump Hien Ryuu Jin Kyaku rush 3rd hit Ryuu Zan Shou HaohShokohKen Super Special Move RyuKo Ranbu Ryo Sakazaki Command Attacks Step Back Sway Fumikomu Kadan Seiken FuusatsuKeri High Spin Kick http://sindoni.altervista.org/neoencyclopedia/ 02/01/04 Art of Fighting 3 [moves] - NEO Encyclopedia 2 / 4 TorageUchi AteKeri KakuGyakuSho mid-level kick Driving Kick jump to edge Triangle Kick mid-level kick Knee Storm crouch Tsurabe Uchi Throw Pursuit Shoulder Throw KimeUchi Special Moves ZanRetsuKen Ko Ou Ken KohGeki Ko Hou HienShippuKyaku HaohShokohKen Super Special Move RyuKo Ranbu Rody Birts Command Attacks Rapid Rod Slide Low Kick Over Swing Dodge Knee Kick Throw Pursuit Hook Throw Bounding Rod Special Moves close Decisive Impact Revolving Rod Middle Impact TT Super Special Move Hyper Tonfa Kasumi Todoh Command Attacks Gohsen SouShoDan Kusanagi sabaki TsuyuBarai SouShoDan SouShoYaritotsuKyaku -

Openpandora Emulator Fact Sheets

Release 1 (Zaxxon) OpenPandora Hotfix 5 Emulator Fact Sheets by Yoshi Version 0.7 1 Table of contents Emulator System Page Getting started 3 Dega Sega Master System 4 DOSBox IBM PC Compatible 5 FBA Arcade 6 GnGeo SNK Neo Geo 7 GnuBoy Nintendo Game Boy Color 8 gpFCE Nintendo NES 9 gpFCE GP2X Nintendo NES 10 gpSP Nintendo Game Boy Advance 11 Handy Atari Lynx 12 HAtari Atari ST 13 HuGo NEC PC Engine / TG-16 14 MAME4ALL Arcade 15 Mednafen NGP SNK Neo Geo Pocket Color 16 Mednafen PCE NEC PC Engine / TG-16 / CD 17 Mupen64plus Nintendo 64 18 PanMAME Arcade 19 PCSX ReARMed Sony Playstation 20 PicoDrive Sega Mega Drive / Genesis / CD / 32X 21 PocketSNES Nintendo SNES 22 RACE SNK Neo Geo Pocket Color 23 Snes9x4P Nintendo SNES 24 Temper NEC PC Engine / TG-16 / CD 25 UAE4ALL Commodore Amiga 26 VICE Commodore C64 27 Quick Reference 28 2 Getting started Setup your SD Card (if you want to use Yoshi‘s Emulator Pack) If you already have a /pandora directory on your SD card, rename it to /pandora_orig . You can 1. also merge selected directories manually instead. Copy the the /pandora folder from Yoshi‘s Pandora Emulator Pack to the root directory of your 2. SD card. All Pandora applications (.pnd) are in /pandora/apps by default. Copy the BIOS and ROM files according to the fact sheets. These files are not included in the 3. emulator pack. SD Card Directory Structure /pandora /appdata Application, ROM and BIOS data /apps Pandora applications appear on desktop and both menus /desktop Pandora applications appear on desktop /menu Pandora applications appear