Cleveland Fire Brigade

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendix a Member Feedback from Conference/Seminar/Fire Related Event

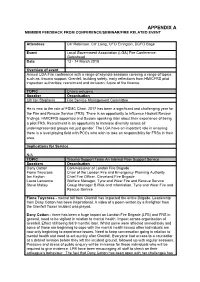

APPENDIX A MEMBER FEEDBACK FROM CONFERENCE/SEMINAR/FIRE RELATED EVENT Attendees Cllr Robinson, Cllr Laing, CFO Errington, DCFO Bage Event Local Government Association (LGA) Fire Conference: Gateshead Date 13 - 14 March 2018 Overview of event Annual LGA Fire conference with a range of keynote sessions covering a range of topics such as: trauma support; Grenfell, building safety, early reflections from HMICFRS pilot inspection authorities; recruitment and inclusion; future of fire finance. TOPIC Chairs welcome Speaker Organisation Cllr Ian Stephens Fire Service Management Committee He is new to the role of FSMC Chair. 2017 has been a significant and challenging year for the Fire and Rescue Service (FRS). There is an opportunity to influence Hackett Review findings. HMICFRS appointed and Sussex speaking later about their experience of being a pilot FRS. Recruitment is an opportunity to increase diversity across all underrepresented groups not just gender. The LGA have an important role in ensuring there is a level playing field with PCCs who wish to take on responsibility for FRSs in their area. Implications for Service N/A TOPIC Trauma Support Team An Internal Peer Support Service Speakers Organisation Dany Cotton Commissioner of London Fire Brigade Fiona Twycross Chair of the London Fire and Emergency Planning Authority Ian Hayton Chief Fire Officer, Cleveland Fire Brigade Laura Lawrence Welfare Manager, Tyne and Wear Fire and Rescue Service Steve Malley Group Manager B Risk and Information, Tyne and Wear Fire and Rescue Service Fiona Twycross - mental toll from Grenfell has impacted the entire Brigade. Leadership from Dany Cotton has been inspirational. A video of a poem written by a firefighter from the Grenfell Tower incident was played. -

Operation Box Clever Cleveland Police

OPERATION BOX CLEVER CLEVELAND POLICE LANGBAURGH DISTRICT CONTACT OFFICER SGT 1248 Dave Lister Management Support Dawson House Ridley Street Redcar Cleveland TS101TT Tel. (01642) 302008 Fax. (01642) 302725 E-mail [email protected] TILLEY AWARD 2000, SUBMISSION SUMMARY PROJECTTITLE- OPERATION BOX CLEVER The Crime and Disorder Audit for the Redcar and Cleveland Borough Council and Langbaurgh District Police identified the alarming fact that the district of Redcar and Cleveland had the highest levels of arson and hoax calls within the U.K. The two adjacent wards of South Bank and Grangetown were the worst affected, and could justifiably be recognised as "the arson capital of the U.K." The Fire Brigade provided evidence of the twenty-five worst performing enumeration districts across the Cleveland area, ten of these were in the South Bank and Grangetown area. Research by the Fire Brigade identified young hoax callers, if unchallenged, can encourage others to make calls. Some hoax callers will progress to fire play and ultimately fire setting. It was further identified that areas with significant social deprivation also had the highest levels of hoax calls and arson. The Fire Brigade had access to a `one to one education service for referred fire-setters, which had a proven success rate in breaking the offending cycle. Historically, the dispatching of Police resources has always been prioritised. Hoax calls made predominantly by children below the age of criminal responsibility were never afforded the necessary commitment or investigative process and very few were identified. The response to the problem would include arson and hoax calls as a priority within the Community Safety Strategy for the district. -

Page 1 MEMBERS of CLEVELAND FIRE AUTHORITY

CLEVELAND FIRE AUTHORITY ORDINARY MEETING 1 2 FEBRUARY 2016 - 2 . 0 0 P M FIRE BRIGADE HEADQUARTERS, STOCKTON ROAD, HARTLEPOOL, TS25 5TB MEMBERS OF CLEVELAND FIRE AUTHORITY - HARTLEPOOL : Councillors - Stephen Akers-Belcher, Rob Cook, Marjorie James , Ray Martin-Wells MIDDLESBROUGH : Councillors - Ronald Arundale, Shamal Biswas, Jan Brunton, Teresa Higgins, Naweed Hussain, Tom Mawston REDCAR & CLEVELAND : Councillors - Billy Ayre, Norah Cooney, Brian Dennis, Ray Goddard, Mary Lanigan, Mary Ovens STOCKTON ON TEES : Councillors - Gillian Corr, John Gardner, Paul Kirton, Jean O’Donnell, Stephen Parry, Mick Stoker, Bill Woodhead A G E N D A 1. APOLOGIES FOR ABSENCE 2. DECLARATIONS OF MEMBERS INTEREST 3. TO CONFIRM THE MINUTES OF PROCEEDINGS OF THE CLEVELAND FIRE AUTHORITY ORDINARY MEETING ON 11 DECEMBER 2015 4. TO CONFIRM THE MINUTES OF COMMITTEES:- Executive Committee on 22 January 2016 5. TO RECEIVE COMMUNICATIONS RECEIVED BY THE CHAIR 6. TO RECEIVE THE REPORTS OF THE CHIEF FIRE OFFICER 6.1 Emergency Services Mobile Communications Programme (ESMCP) 6.2 Public Consultation on Emergency Services 6.3 Community Integrated Risk Management Plan (CIRMP) Annual Review – Alternative Proposal: Three Watch Duty System 6.4 Draft Service Plan Priorities 2016/17 6.5 Safeguarding Children, Young People and Vulnerable Adults Policy 6.6 Information Pack 7. TO RECEIVE THE JOINT REPORT OF THE CHIEF FIRE OFFICER AND TREASURER 7.1 Medium Term Financial Strategy 2016/17 - 2019/20 CLEVELAND FIRE AUTHORITY O R D I N A R Y MEETING 1 2 F E B R U A R Y 2 0 1 6 - 2 . 0 0 PM FIRE BRIGADE HEADQUARTERS, STOCKTON ROAD, HARTLEPOOL, TS25 5TB A G E N D A - 2 - 8. -

August Newsletter

AGE UK T EESSIDE M O N T H L Y N E W S L E T T E R - A U G U S T 2 0 1 9 Cadbury Donate Your Words Campaign 30p from every promotional bar goes to Age UK Add a little bit of body text Join Age UK and Cadbury to Fight Loneliness 225,000 older people often go a whole week without speaking to anyone. Cadbury are donating the words from their Cadbury Dairy Milk bars to help - and you can too. Volunteer Story Stockton on Tees Parkrunner John Hirst, who lost his wife to dementia in 2017 when she was just 66 years old, will be running the equivalent of a marathon at the 8 Parkrun & 1 junior Parkrun courses along the A66 within 24 hours to raise money for the UK’s leading dementia research charity Alzheimer’s Research UK. John is the lead volunteer for our Dementia Walking group and is aiming to raise £1,000 to help fund vital dementia research and would welcome support from anyone who would like to join him on one or more legs of the challenge. On 6th September John will be 66yr 7mth 5days (24,324 days) old, the exact age reached by his wife. Fri 6th Sept: 10:00 Workington; 11:45 Whinlatter Forest; 13:15 Keswick; 15:15 Penrith; 17:45 Darlington South Park; 19:15 Billingham Juniors; 20.00 Tees Barrage. Sat 7th Sept: 07:15 Albert, Middlesbrough; 09:00 Redcar. To sponsor John visit: www.justgiving.com/fundraising/a66parkrunmarathon Strollers & Stragglers Mondays 10:00 - 12:00 A walking group for people with Dementia and their carers.* Walking routes will rotate, including: Tees Barrage Ropner Park Preston Park Thornaby Stewart Park Norton September 2019 2nd Teesside Barrage The session will include a local walk 9th Ropner Park and refreshments in a social setting. -

9 June 2017 (PDF)

CLEVELAND FIRE AUTHORITY O R D I N A R Y MEETING 9 J U N E 2 0 1 7 - 11. 0 0 A M CLEVELAND FIRE BRIGADE, TRAINING & ADMINISTRATION HUB, ENDEAVOUR HOUSE, QUEENS MEADOW BUSINESS PARK, HARTLEPOOL, TS25 5TH MEMBERS OF CLEVELAND FIRE AUTHORITY - HARTLEPOOL : Councillors - Rob Cook, Marjorie James, Ray Martin-Wells MIDDLESBROUGH : Councillors - Jan Brunton, Teresa Higgins, Naweed Hussain, Tom Mawston REDCAR & CLEVELAND : Councillors - Neil Bendelow, Norah Cooney, Ray Goddard, Mary Ovens STOCKTON ON TEES : Councillors - Gillian Corr, Paul Kirton, Jean O’Donnell, Mick Stoker, Bill Woodhead A M E N D E D A G E N D A 1. APOLOGIES FOR ABSENCE 2. DECLARATIONS OF MEMBERS INTEREST 3. TO CONFIRM THE MINUTES OF:- 3.1 Executive (Appointments) Committee - 21 April 2017 3.2 Executive Committee - 12 May 2017 3.3 Audit & Governance Committee - 19 May 2017 3.4 Cleveland Fire Authority Annual Meeting – 2 June 2017 4a TO RECEIVE COMMUNICATIONS RECEIVED BY THE CHAIR 4b TO RECEIVE THE REPORT OF THE LEGAL ADVISER AND MONITORING OFFICER - Business Report 2017/18 (deferred from 02/06/17) 5. TO RECEIVE THE REPORTS OF THE CHIEF FIRE OFFICER 5.1 Annual Performance and Efficiency Report 2016/17 5.2 Strategic Planning and Community Integrated Risk Management Plan 2018/19 – 2021/22 5.3 Information Pack 6. ANY OTHER BUSINESS WHICH, IN THE OPINION OF THE CHAIR, SHOULD BE CONSIDERED AS A MATTER OF URGENCY OFFICIAL CLEVELAND FIRE AUTHORITY O R D I N A R Y MEETING 9 J U N E 2 0 1 7 - 11.00A M CLEVELAND FIRE BRIGADE, TRAINING & ADMINISTRATION HUB, ENDEAVOUR HOUSE, QUEENS MEADOW BUSINESS PARK, HARTLEPOOL, TS25 5TH A M E N D E D A G E N D A - 2 - 7. -

Equality, Diversity and Inclusion Strategy 2018- 2022

OFFICIAL Equality, Diversity and Inclusion Strategy 2018- 2022 People Policy Process Equality, Diversity and Inclusivity Policy Authored by: Director of Corporate Services ELT Approved: 22nd August 2017 FBU Consultation: August/September 2017 Unison Consultation: August/September 2017 nd Executive Committee 22 September 2017 Approved: Policy and Strategy September 2022 Register Review Date: Implementing Officer: Head of Human Resources Other Relevant Strategies Equality, Diversity and Inclusion and cuts across all other strategies in one way or another. However this strategy particularly positively impacts our community safety and workforce strategies. 2 | P a g e Equality, Diversity and Inclusion Strategy V7 If you require this document in an alternative language, large print or Braille, please do not hesitate to contact us. إذا كنت تحتاج إلى هذا المستند بلغة بديلة أو مطبوع بأحرف كبيرة أو بطريقة برايل، فﻻ تتردد في اﻻتصال بنا. আপনার যদি এই নদি綿 এক綿 দিকল্প ভাষা, িড় হরফের মুদ্রন িা ব্রেইফে প্রফয়াজন হয়, আমাফির সাফি ব্রযাগাফযাগ করফে দিধা করফিন না। Pokud potřebujete tento dokument v alternativním jazyce, velkém tisku nebo Braillově písmu, neváhejte nás kontaktovat. اگر اين نوشتار را به زبانی ديگر، با چاپ درشت يا خط بريل ﻻزم داريد، لطفاً با ما تماس بگيريد. Kung nangangailangan ka ng dokumentong ito sa isang alternatibong wika, malaking print o Braille, mangyaring huwag mag-atubiling makipag-ugnay sa amin Eger tu vê belgeyê bi zimanê Kurdî, çapa bi tîpên mezin an Xetê Brîl dixwazî bi hetim bi me ra têkilliyê bigir. 如果您需要本文件的其他语言版本、大字版本或盲文版本,请随时与我们联系 Jeśli chcieliby Państwo otrzymać ten dokument w innym języku, w wersji dużym drukiem lub pisany alfabetem Braille'a, prosimy o kontakt z nami. -

Age UK Teesside Are Saying a Special Thank You to the 10Th Guisborough Brownies, Who Raised £110 for Each of the Following Charities

1 2 Guisborough Brownies 3 Dementia Walking Group 4-5 Warm Homes 6 Safe & Well in Winter 7 Event: Dance Through Time 8 Christmas Carol Concert 9 Friendship Friday 10 MCST 11 Phoenix Project 12-14 Living With & Beyond Cancer 15 Better Health Better Wealth Activity Schedule 16 FRADE: Men’s Shed 17 The Innocent Big Knit 18-19 Middlesbrough Befriending 20 Stockton Befriending Service 21 Hartlepool Befriending Network 22-23 Redcar Befriending Service 24-25 Festive Lunch: Stockton 26 Festive Lunch: Middlesbrough 27 Festive Lunch: Hartlepool 28 Festive Lunch: Redcar 29 I & A: Community Hub Advice in Middlesbrough 30 Trustees Wanted 31 Event: March Against Loneliness 32 Good to Know! Useful Contacts in Teesside! 33 Co-Op Local Cause (Back) 34 3 Guisborough Brownies Age UK Teesside are saying a special thank you to the 10th Guisborough Brownies, who raised £110 for each of the following charities: Age UK Teesside Kirkleatham Hall School The Link Morrisons Maxi’s Mates The Brownies packed shopping bags in Morrison’s supermarket to raise money and gain their charities badge. Louise Wheatley, Operations Manager, went along to support the Brownies and to their presentation ceremony to accept the cheque on Age UK Teesside’s behalf. Thank you for your hard work Brownies and thank you to Morrisons’ shoppers for your generous donations. 4 5 Dementia Walking Group Come and join our Dementia Walking Group; walkers meet at the Live Well Dementia Hub in Thornaby before embarking on one of 4 routes, that will rotate on a 4-weekly basis. Routes include: The Tees Barrage Ropner Park Preston Park Thornaby Area All are welcome to join the sessions and enjoy a walk at a relaxed pace followed by refresh- ments. -

Download the Agenda and Reports

p SAFER HARTLEPOOL PARTNERSHIP AGENDA Friday 4 September 2020 at 10.00 am in the Council Chamber, Civic Centre, Hartlepool PLEASE NOTE: this will be a ‘remote meeting’, a web-link to the public stream will be available on the Hartlepool Borough Council website at least 24 hours before the meeting. MEMBERS: SAFER HARTLEPOOL PARTNERSHIP Responsible Authority Members: Councillor Moore, Elected Member, Hartlepool Borough Council Councillor Tennant, Elected Member, Hartlepool Borough Council Gill Alexander, Chief Executive, Hartlepool Borough Council Tony Hanson, Assistant Director, Environment and Neighbourhood Services, Hartlepool Borough Council Sylvia Pinkney, Interim Assistant Director, Regulatory Services, Hartlepool Borough Council Superintendent Sharon Cooney, Neighbourhood Partnership and Policing Command, Cleveland Police Chief Inspector Peter Graham, Chair of Youth Offending Board Michael Houghton, Director of Commissioning, Strategy and Delivery, NHS Hartlepool and Stockton on Tees and Darlington Clinical Commissioning Group Ann Powell, Head of Area, Cleveland National Probation Service John Graham, Director of Operations, Durham Tees Valley Community Rehabilitation Company Nick Jones, Cleveland Fire Authority Other Members: Craig Blundred, Acting Director of Public Health, Hartlepool Borough Council Barry Coppinger, Office of Police and Crime Commissioner for Cleveland Joanne Hodgkinson, Voluntary and Community Sector Representative, Chief Executive, Safe in Tees Valley Angela Corner, Director of Customer Support, Thirteen Group Sally Robinson, Director of Children’s and Joint Commissioning Services, Hartlepool Borough Council Jill Harrison, Director of Adult and Community Based Services, Hartlepool Borough Council 1. APPOINTMENT OF VICE CHAIR 2. APOLOGIES FOR ABSENCE www.hartlepool.gov.uk/democraticservices 3. TO RECEIVE ANY DECLARATIONS OF INTEREST BY MEMBERS 4. MINUTES 4.1 To confirm the minutes of the meeting held on 10 January 2020 4.2 To confirm the minutes of the meeting held on 20 March 2020 5. -

Stockton-On-Tees News May 2021

May 2021 The community magazine of Stockton-on-Tees Borough Council Stockton- on-Tees News www.stockton.gov.uk/stocktononteesnews Welcome to the May edition of Stockton-on- SIRF | 08 Lockdown Legend | 11 Tees News. Over the last few weeks we’ve seen COVID restrictions begin to ease and it has been great to see so many of you out and about enjoying our town centres, leisure facilities, parks and green spaces. There’s lots of information in this edition about the things you can now enjoy including activities at Tees Active leisure centres on page 15 and walks across the Borough on pages 12 and 13. Turn to page 26 to learn about the steps that have been taken to make your visits to our six town centres as safe as possible. There’s lots of exciting news for us to share with you in this edition of the magazine, the restoration of the Globe Stockton Join is now complete and on pages 6 and 7 you can read all about it and how you can win tickets to some of the first shows. Walk this way | 12 Tees Active | 15 And we’re delighted to announce that Stockton International Riverside Festival is returning this summer. The COVID restrictions meant that we had to switch to a virtual festival the millions last year but this summer you’ll be able to enjoy four days Contents packed full of free street theatre, circus, dance and music with something for all the family. Make sure you save the dates – Thursday 29 July until Sunday 1 August. -

Operational Guidance Breathing Apparatus

This document was archived on 30 March 2020 Operational guidance Breathing apparatus Breathing guidance Operational OperationalArchived guidance Breathing apparatus This document was archived on 30 March 2020 OperationalArchived guidance Breathing apparatus This document was archived on 30 March 2020 Published by TSO (The Stationery Office) and available from: Online www.tsoshop.co.uk Mail, Telephone, Fax & E-mail TSO PO Box 29, Norwich, NR3 1GN Telephone orders/General enquiries: 0870 600 5522 Fax orders: 0870 600 5533 E-mail: [email protected] Textphone 0870 240 3701 TSO@Blackwell and other Accredited Agents Published with the permission of the Department for Communities and Local Government on behalf of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. © Crown copyright, 2014 ISBN 9780117541146 Copyright in the typographical arrangement rests with the Crown. You may re-use this information (not including logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence. To view this licence, www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/openArchived-government-licence/ or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected]. This document/publication is also available on our website at www.gov.uk/dclg If you have any enquiries regarding this document/publication, email [email protected] or write to us at: Department for Communities and Local Government Eland House Bressenden Place London SW1E 5DU Telephone: 030 3444 0000 January 2014 Printed in -

Equality, Diversity and Inclusion Strategy 2018 - 2022

OFFICIAL Equality, Diversity and Inclusion Strategy 2018 - 2022 People Policy Process Equality, Diversity and Inclusivity Policy Authored by: Director of Corporate Services ELT Approved: 22nd August 2017 FBU Consultation: August/September 2017 Unison Consultation: August/September 2017 nd Executive Committee 22 September 2017 Approved: Policy and Strategy September 2022 Register Review Date: Implementing Officer: Head of Human Resources Other Relevant Strategies Equality, Diversity and Inclusion and cuts across all other strategies in one way or another. However this strategy particularly positively impacts our community safety and workforce strategies. 2 | P a g e OFFICIAL - Equality, Diversity and Inclusion Strategy V8 If you require this document in an alternative language, large print or Braille, please do not hesitate to contact us. إذا كنت تحتاج إلى هذا المستند بلغة بديلة أو مطبوع بأحرف كبيرة أو بطريقة برايل، فﻻ تتردد في اﻻتصال بنا. আপনার যদি এই নথিটি একটি বিকল্প ভাষা, বড় হরফের মুদ্রন বা ব্রেইলে প্রয়োজন হয়, আমাদের সাথে যোগাযোগ করতে দ্বিধা করবেন না। Pokud potřebujete tento dokument v alternativním jazyce, velkém tisku nebo Braillově písmu, neváhejte nás kontaktovat. اگر اين نوشتار را به زبانی ديگر، با چاپ درشت يا خط بريل ﻻزم داريد، لطفاً با ما تماس بگيريد. Kung nangangailangan ka ng dokumentong ito sa isang alternatibong wika, malaking print o Braille, mangyaring huwag mag-atubiling makipag-ugnay sa amin Eger tu vê belgeyê bi zimanê Kurdî, çapa bi tîpên mezin an Xetê Brîl dixwazî bi hetim bi me ra têkilliyê bigir. 如果您需要本文件的其他语言版本、大字版本或盲文版本,请随时与我们联系 Jeśli chcieliby Państwo otrzymać ten dokument w innym języku, w wersji dużym drukiem lub pisany alfabetem Braille'a, prosimy o kontakt z nami. -

Future Control Room Improvement Government Update on Fire and Rescue Authority Scheme

Future Control Room Improvement Future Control Room Improvement Government update on fire and rescue authority scheme November 2016 1 Future Control Room Improvement © Crown copyright 2016 This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open- government-licence/version/3 or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected]. Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. This publication is available at www.gov.uk/government/publications 2 Future Control Room Improvement Contents Government update on fire and rescue authority scheme 1 Document purpose 5 FiReControl 5 The Future Control Room Services Scheme 5 Summary Assessment 7 Project completion and progress 7 The project partnerships 8 Coverage that will be provided as the Control Room Projects complete 9 Delivery of the resilience benefits 10 Financial Benefits 11 Comparing the benefits to FiReControl - Resilience of the system now 12 Locally delivered projects helping to secure national resilience 13 Delivery arrangements 16 The remaining projects 16 Next steps 17 Analysis 19 Timescales for completing the improvements 19 How the timescales for completing the improvements compare with the summary of March 2012 21 Planned resilience improvements 21 Progress against the October 2009 baseline towards completion