Study Guides

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inseparable Faith: Exploring Manifestations and Experiences of Faith-Work Integration in Young Alumni from a Christian University Emilie Hoffman Taylor University

Taylor University Pillars at Taylor University Master of Arts in Higher Education Thesis Collection 2017 Inseparable Faith: Exploring Manifestations and Experiences of Faith-Work Integration in Young Alumni from a Christian University Emilie Hoffman Taylor University Follow this and additional works at: https://pillars.taylor.edu/mahe Part of the Higher Education Commons Recommended Citation Hoffman, Emilie, "Inseparable Faith: Exploring Manifestations and Experiences of Faith-Work Integration in Young Alumni from a Christian University" (2017). Master of Arts in Higher Education Thesis Collection. 90. https://pillars.taylor.edu/mahe/90 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Pillars at Taylor University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master of Arts in Higher Education Thesis Collection by an authorized administrator of Pillars at Taylor University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INSEPARABLE FAITH: EXPLORING MANIFESTATIONS AND EXPERIENCES OF FAITH-WORK INTEGRATION IN YOUNG ALUMNI FROM A CHRISTIAN UNIVERSITY _______________________ A thesis Presented to The School of Social Sciences, Education & Business Department of Higher Education and Student Development Taylor University Upland, Indiana ______________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Higher Education and Student Development _______________________ by Emilie Hoffman May 2017 Emilie Hoffman 2017 Higher Education and Student Development Taylor University Upland, Indiana CERTIFICATE OF APPROVAL _________________________ MASTER’S THESIS _________________________ This is to certify that the Thesis of Emilie Hoffman entitled Inseparable Faith: Exploring Manifestations and Experiences of Faith-Work Integration in Young Alumni from a Christian University has been approved by the Examining Committee for the thesis requirement for the Master of Arts degree in Higher Education and Student Development May 2017 __________________________ _____________________________ Drew Moser, Ph.D. -

Mysticism in Indian Philosophy

The Indian Institute of World Culture Basavangudi, Bangalore-4 Transaction No.36 MYSTICISM IN INDIAN PHILOSOPHY BY K. GOPALAKRISHNA RAO Editor, “Jeevana”, Bangalore 1968 Re. 1.00 PREFACE This Transaction is a resume of a lecture delivered at the Indian Institute of World Culture by Sri K. Gopala- Krishna Rao, Poet and Editor, Jeevana, Bangalore. MYSTICISM IN INDIAN PHILOSOPHY Philosophy, Religion, Mysticism arc different pathways to God. Philosophy literally means love of wisdom for intellectuals. It seeks to ascertain the nature of Reality through sense of perception. Religion has a social value more than that of a spiritual value. In its conventional forms it fosters plenty but fails to express the divinity in man. In this sense it is less than a direct encounter with reality. Mysticism denotes that attitude of mind which involves a direct immediate intuitive apprehension of God. It signifies the highest attitude of which man is capable, viz., a beatific contemplation of God and its dissemination in society and world. It is a fruition of man’s highest aspiration as an integral personality satisfying the eternal values of life like truth, goodness, beauty and love. A man who aspires after the mystical life must have an unfaltering and penetrating intellect; he must also have a powerful philosophic imagination. Accurate intellectual thought is a sure accompaniment of mystical experience. Not all mystics need be philosophers, not all mystics need be poets, not all mystics need be Activists, not all mystics lead a life of emotion; but wherever true mysticism is, one of these faculties must predominate. A true life of mysticism teaches a full-fledged morality in the individual and a life of general good in the world. -

Introduction to Evelyn Underhill, “Church Congress Syllabus No. 3: the Christian Doctrine of Sin and Salvation, Part III: Worship”

ATR/100.3 Introduction to Evelyn Underhill, “Church Congress Syllabus No. 3: The Christian Doctrine of Sin and Salvation, Part III: Worship” Kathleen Henderson Staudt* This short piece by Evelyn Underhill (1875–1941) appeared in a publication from the US Church Congress movement in the 1930s. It presents a remarkably concise summary of her major thought from this period.1 By this time, she was a well-known voice among Angli- cans. Indeed, Archbishop Michael Ramsey wrote that “in the twenties and thirties there were few, if indeed, any, in the Church of England who did more to help people to grasp the priority of prayer in the Christian life and the place of the contemplative element within it.”2 Underhill’s major work, Mysticism, continuously in print since its first publication in 1911, reflects at once Underhill’s broad scholarship on the mystics of the church, her engagement with such contemporaries as William James and Henri Bergson, and, perhaps most important, her curiosity and insight into the ways that the mystics’ experiences might inform the spiritual lives of ordinary people.3 The title of a later book, Practical Mysticism: A Little Book for Normal People (1914) summarizes what became most distinctive in Underhill’s voice: her ability to fuse the mystical tradition with the homely and the * Kathleen Henderson Staudt works as a teacher, poet, and spiritual director at Virginia Theological Seminary and Wesley Theological Seminary. Her poetry, essays, and reviews have appeared in Weavings, Christianity and Literature, Sewanee Theo- logical Review, Ruminate, and Spiritus. She is an officer of the Evelyn Underhill As- sociation, and facilitates the annual day of quiet held in honor of Underhill in Wash- ington, DC each June. -

Theology Is Everywhere 2.3: the Path of Mysticism Cosmology

Theology is Everywhere 2.3: The Path of Mysticism Cosmology & Worldview The Paradox of the Mystical Life Mysticism defined Figurative Language Poetry & Mysticism Other Paradoxes: the Particular and the Universal Christian Mysticism - Imitation of Christ Mystical Interpretation: allegory. St. Teresa of Avila (1515–1582): Nada te turbe…sola Dios basta! Via Negativa (Apophatic Theology) & Via Positiva (Cataphatic Theology) Mystical Union: Ecstacy (Standing outside oneself) The Mystic Path: The Science of Removing Mental Limitations 1. The Awakening: 2. Purgation 3. Illumination 4. The Dark Night of the Soul: Embracing times of shadow 5. Union With the Divine: Ultimate Reality Be lover and Beloved Hesychasm: Divine Silence Embraced by Uncreated Light Walking the Labyrinth So what’s a mystic? Mysticism & Intimacy with God: Jesus and his Friend “I am my beloved’s and he is mine.” ~ Song of Solomon 2:16 Evelyn Underhill quote: “Mysticism offers us the history, as old as civilization, of a race of adventurers who have carried to its term the process of a deliberate and active return to the divine fount of things. They have surrendered themselves to the life-movement of the universe, hence have lived an intenser life than other beings can even know…. Therefore they witness to all that our latent spiritual consciousness, which shows itself in the ‘hunger for the absolute,’ can be made to mean to us if we develop it, and have in this respect an unique importance for the race.”~ Mysticism Ethics and Mysticism: Howard Thurman "Don't ask yourself what the world needs. Ask yourself what makes you come alive and then go do that. -

The Theosophist

THE THEOSOPHIST VOL. 133 NO. 2 NOVEMBER 2011 CONTENTS Buddhist Teachings on Relationships 3 Radha Burnier Live the Life and You Will Come to the Wisdom 8 Mary Anderson Coordination of Science and Human Values 14 C. A. Shinde Some Difficulties of the Inner Life — II 19 Annie Besant The Roots of Modern Theosophy 25 Pablo D. Sender The Life-Path of a Theosophist 32 Vinayak Pandya Theosophical Work around the World 37 International Directory 38 Editor: Mrs Radha Burnier NOTE: Articles for publication in The Theosophist should be sent to the Editorial Office. Cover Picture: Gate at the Headquarters Hall — by Richard Dvorak Official organ of the President, founded by H. P. Blavatsky, 1879. The Theosophical Society is responsible only for official notices appearing in this magazine. 1 THE THEOSOPHICAL SOCIETY Founded 17 November 1875 President: Mrs Radha Burnier Vice-President: Mrs Linda Oliveira Secretary: Mrs Kusum Satapathy Treasurer: Miss Keshwar Dastur Headquarters: ADYAR, CHENNAI (MADRAS) 600 020, INDIA Secretary: [email protected] Treasury: [email protected] Adyar Library and Research Centre: [email protected] Theosophical Publishing House: [email protected] & [email protected] Fax: (+91-44) 2490-1399 Editorial Office: [email protected] Website: http://www.ts-adyar.org The Theosophical Society is composed of students, belonging to any religion in the world or to none, who are united by their approval of the Society’s Objects, by their wish to remove religious antagonisms and to draw together men of goodwill, whatsoever their religious opinions, and by their desire to study religious truths and to share the results of their studies with others. -

Understanding Our Seven Principles

UNDERSTANDING OUR SEVEN PRINCIPLES A COMPILATION FROM H. P. BLAVATSKY AND WILLIAM Q. JUDGE Atma “Pure universal Spirit.” ["The Key to Theosophy" p. 92] "Higher Self. The Supreme Divine Spirit overshadowing man. The crown of the upper spiritual Triad in man - Atman." ["The Theosophical Glossary" p. 141, Entry for "Higher Self"] “Atma, the “Higher Self,” is neither your Spirit nor mine, but like sunlight shines on all. It is the universally diffused “divine principle,” and is inseparable from its one and absolute Meta-Spirit, as the sunbeam is inseparable from the sunlight.” ["The Key to Theosophy" p. 135] “This “Higher Self” is ATMA, and of course it is “non-materializable” … Even more, it can never be “objective” under any circumstances, even to the highest spiritual perception. For Atman or the “Higher Self” is really Brahman, the ABSOLUTE, and indistinguishable from it.” ["The Key to Theosophy" p. 174] “THE HIGHER SELF is - Atma, the inseparable ray of the Universal and ONE SELF. It is the God above, more than within, us. Happy the man who succeeds in saturating his inner Ego with it!” ["The Key to Theosophy" p. 175] “We apply the term Spirit, when standing alone and without any qualification, to Atma alone.” ["The Key to Theosophy" p. 115] “In hours of Samadhi, the higher spiritual consciousness of the Initiate is entirely absorbed in the ONE essence, which is Atman, and therefore, being one with the whole, there can be nothing objective for it. Now some of our Theosophists have got into the habit of using the words “Self” and “Ego” as synonymous, of associating the term “Self” with only man’s higher individual or even personal “Self” or Ego, whereas this term ought never to be applied except to the One universal Self.” ["The Key to Theosophy" p. -

A Response to Grypma & Commentary on Mysticism

69059 JCNSummer06 05/03/2006 12:26 PM Page 27 A Response to Grypma & Commentary on Mysticism BY BARBARA MONTGOMERY DOSSEY “MYSTICISM ...IS NOT AN OPINION: IT IS NOT A PHILOSOPHY. It has nothing in common with the pursuit of occult knowledge.On the one hand,it is not merely the power of contemplating Eter- nity: on the other, it is not to be identified with any kind of religious queerness. It is the name of that organic process which involves the perfect consummation of the Love of God: the achieve- ment here and now of the immortal heritage of man.Or,if you like it better—for this means exactly the same thing—it is the art of establishing his conscious relation with the Absolute.”1 E VELYN U NDERHILL,MYSTICISM, 1911 extend my thanks to Dr. founder3 of modern secular nursing. nitions and criteria according to which Grypma2 and the Journal of However, there are many issues on Nightingale qualifies as a full-fledged, Christian Nursing for atten- which Dr. Grypma and I disagree in nineteenth-century “practical mystic.” tion to Florence Nightin- our analysis of Nightingale.We seem to What does Dr. Grypma consider a gale (1820-1910), the be far apart on the essential meanings mystic to be? I am left wondering.This philosophical and practical of terms such as “mystic,”“mysticism” does not prevent her, however, from and “spirituality”—yet it is difficult to suggesting that the classification of ■ Barbara Montgomery know for certain because Dr. Grypma Nightingale as a mystic is a “New Age” Dossey, PhD, FAAN, RN, is nowhere defines explicitly what she and “postmodern” move. -

Evelyn Underhill's Concept of Mysticism and Its Relation To

This material has been provided by Asbury Theological Seminary in good faith of following ethical procedures in its production and end use. The Copyright law of the united States (title 17, United States code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyright material. Under certain condition specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to finish a photocopy or other reproduction. One of these specific conditions is that the photocopy or reproduction is not to be “used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research.” If a user makes a request for, or later uses, a photocopy or reproduction for purposes in excess of “fair use,” that user may be liable for copyright infringement. This institution reserves the right to refuse to accept a copying order if, in its judgment, fulfillment of the order would involve violation of copyright law. By using this material, you are consenting to abide by this copyright policy. Any duplication, reproduction, or modification of this material without express written consent from Asbury Theological Seminary and/or the original publisher is prohibited. Contact B.L. Fisher Library Asbury Theological Seminary 204 N. Lexington Ave. Wilmore, KY 40390 B.L. Fisher Library’s Digital Content place.asburyseminary.edu Asbury Theological Seminary 205 North Lexington Avenue 800.2ASBURY Wilmore, Kentucky 40390 asburyseminary.edu Evelyn Underbill's Concept of Mysticism and Its Relation to Common Misrepresentations by Kendra Irons A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS ASBURY THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY 1993 Approved by CJh^y^^MjJ^-^^^ . -

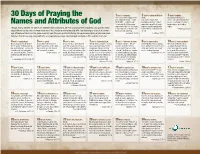

30 Days of Praying the Names and Attributes Of

30 Days of Praying the 1 God is Jehovah. 2 God is Jehovah-M’Kad- 3 God is infinite. The name of the independent, desh. God is beyond measure- self-complete being—“I AM This name means “the ment—we cannot define Him WHO I AM”—only belongs God who sanctifies.” A God by size or amount. He has no Names and Attributes of God to Jehovah God. Our proper separate from all that is evil beginning, no end, and no response to Him is to fall down requires that the people who limits. Though God is infinitely far above our ability to fully understand, He tells us through the Scriptures very specific truths in fear and awe of the One who follow Him be cleansed from —Romans 11:33 about Himself so that we can know what He is like, and be drawn to worship Him. The following is a list of 30 names possesses all authority. all evil. and attributes of God. Use this guide to enrich your time set apart with God by taking one description of Him and medi- —Exodus 3:13-15 —Leviticus 20:7,8 tating on that for one day, along with the accompanying passage. Worship God, focusing on Him and His character. 4 God is omnipotent. 5 God is good. 6 God is love. 7 God is Jehovah-jireh. 8 God is Jehovah-shalom. 9 God is immutable. 10 God is transcendent. This means God is all-power- God is the embodiment of God’s love is so great that He “The God who provides.” Just as “The God of peace.” We are All that God is, He has always We must not think of God ful. -

The Correlation Between Theology and Worship

Running head: THE CORRELATION BETWEEN THEOLOGY AND WORSHIP The Correlation Between Theology and Worship Tyler Thompson A Senior Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation in the Honors Program Liberty University Spring 2018 THE CORRELATION BETWEEN THEOLOGY AND WORSHIP Thompson 1 Acceptance of Senior Honors Thesis This Senior Honors Thesis is accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation from the Honors Program of Liberty University. ______________________________ Rick Jupin, D.M.A. Thesis Chair ______________________________ Keith Cooper, M.A. Committee Member ______________________________ David Wheeler, P.H.D. Committee Member ______________________________ Chris Nelson, M.F.A. Assistant Honors Director THE CORRELATION BETWEEN THEOLOGY AND WORSHIP Thompson 2 ______________________________ Date Abstract This thesis will address the correlation between theology and worship. Firstly, it will address the process of framing a worldview and how one’s worldview influences his thinking. Secondly, it will contrast flawed views of worship with the biblically defined worship that Christ calls His followers to practice. Thirdly, it will address the impact of theology in the life of a believer and its necessity and practice in the lifestyle of a worship leader. THE CORRELATION BETWEEN THEOLOGY AND WORSHIP Thompson 3 The Correlation Between Worship and Theology Introduction Since creation, mankind was designed to devote its heart, soul, and mind to the Sovereign God of all (Rom. 1:18-20). As an outward sign of this commitment and devotion, mankind would live in accordance with the established, inerrant, and absolute truths of God (Matt. 22:37, John 17:17). Unfortunately, as a consequence of man’s disobedience, many beliefs have arisen which tempt mankind to replace God’s absolute truth as the basis of their worldview (Rom. -

The Theosophist

THE THEOSOPHIST VOL. 135 NO. 7 APRIL 2014 CONTENTS On the Watch-Tower 3 M. P. Singhal The many lives of Siddhartha 7 Mary Anderson The Voice of the Silence — II 13 Clara Codd Charles Webster Leadbeater and Adyar Day 18 Sunita Maithreya Regenerating Wisdom 21 Krishnaphani Spiritual Ascent of Man in Secret Doctrine 28 M. A. Raveendran The Urgency for a New Mind 32 Ricardo Lindemann International Directory 38 Editor: Mr M. P. Singhal NOTE: Articles for publication in The Theosophist should be sent to the Editorial Office. Cover: Common Hoope, Adyar —A. Chandrasekaran Official organ of the President, founded by H. P. Blavatsky, 1879. The Theosophical Society is responsible only for official notices appearing in this magazine. 1 THE THEOSOPHICAL SOCIETY Founded 17 November 1875 President: Vice-President: Mr M. P. Singhal Secretary: Dr Chittaranjan Satapathy Treasurer: Mr T. S. Jambunathan Headquarters: ADYAR, CHENNAI (MADRAS) 600 020, INDIA Secretary: [email protected] Treasury: [email protected] Adyar Library and Research Centre: [email protected] Theosophical Publishing House: [email protected] & [email protected] Fax: (+91-44) 2490-1399 Editorial Office: [email protected] Website: http://www.ts-adyar.org The Theosophical Society is composed of students, belonging to any religion in the world or to none, who are united by their approval of the Society’s Objects, by their wish to remove religious antagonisms and to draw together men of goodwill, whatsoever their religious opinions, and by their desire to study religious truths and to share the results of their studies with others. Their bond of union is not the profession of a common belief, but a common search and aspiration for Truth. -

Hinduism and Hindu Philosophy

Essays on Indian Philosophy UNIVE'aSITY OF HAWAII Uf,FU:{ Essays on Indian Philosophy SHRI KRISHNA SAKSENA UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII PRESS HONOLULU 1970 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 78·114209 Standard Book Number 87022-726-2 Copyright © 1970 by University of Hawaii Press All Rights Reserved Printed in the United States of America Contents The Story of Indian Philosophy 3 Basic Tenets of Indian Philosophy 18 Testimony in Indian Philosophy 24 Hinduism 37 Hinduism and Hindu Philosophy 51 The Jain Religion 54 Some Riddles in the Behavior of Gods and Sages in the Epics and the Puranas 64 Autobiography of a Yogi 71 Jainism 73 Svapramanatva and Svapraka!;>atva: An Inconsistency in Kumarila's Philosophy 77 The Nature of Buddhi according to Sankhya-Yoga 82 The Individual in Social Thought and Practice in India 88 Professor Zaehner and the Comparison of Religions 102 A Comparison between the Eastern and Western Portraits of Man in Our Time 117 Acknowledgments The author wishes to make the following acknowledgments for permission to reprint previously published essays: "The Story of Indian Philosophy," in A History of Philosophical Systems. edited by Vergilius Ferm. New York:The Philosophical Library, 1950. "Basic Tenets of Indian Philosophy," previously published as "Are There Any Basic Tenets of Indian Philosophy?" in The Philosophical Quarterly. "Testimony in Indian Philosophy," previously published as "Authority in Indian Philosophy," in Ph ilosophyEast and West. vo!.l,no. 3 (October 1951). "Hinduism," in Studium Generale. no. 10 (1962). "The Jain Religion," previously published as "Jainism," in Religion in the Twentieth Century. edited by Vergilius Ferm.