Executive Council Confidential

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From Penguins to Pandas - the Conservation Game

From Penguins to Pandas - the conservation game Falkland Islands Animal Fact Files © RZSS 2014 Falkland Islands The Falkland Islands are 1,365km (850 miles) north of Antarctica. They are 644km (400 miles) off the south eastern tip of South America and 12,900km (8000 miles) from Scotland. They consist of 2 main islands, East and West Falkland and 776 smaller islands. The Falkland Islands is an overseas territory of the UK which is independent and self governing except for defence and foreign affairs. The total land area is 12,173 sq km (4700 sq miles). The population is approximately 2900 and about 1000 military personnel. 75% of the population live in Stanley, the capital. There are however about 500,000 sheep on the islands! The main employment in the country is from fisheries, tourism and sheep farming. The currency (the money used in the country) is the Falkland Islands pound which is the same as the British pound but their notes and coins have lovely pictures of penguins and other wildlife on them. Falkland Islands Animal Fact Files The fact files on the following pages, not only provide some information on the animal but also a link to a similar animal in Scotland. Find out some interesting facts about these animals. Write the fact in the space provided for extra information. 2 3 4 5 6 7 95cm 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Please also see the following resource in this pack: Penguins of the Falkland Islands To find out more about ‘From Penguins to Pandas’ outreach programme, contact: Sandie Robb, Senior Education Officer, RZSS—[email protected] -

Country Scheme Alpha 3 Alpha 2 Currency Albania MC / VI ALB AL

Country Scheme Alpha 3 Alpha 2 Currency Albania MC / VI ALB AL Lek Algeria MC / VI DZA DZ Algerian dinar Argentina MC / VI ARG AR Argentine peso Australia MC / VI AUS AU Australian dollar -Christmas Is. -Cocos (Keeling) Is. -Heard and McDonald Is. -Kiribati -Nauru -Norfolk Is. -Tuvalu Christmas Island MC CXR CX Australian dollar Cocos (Keeling) Islands MC CCK CC Australian dollar Heard and McDonald Islands MC HMD HM Australian dollar Kiribati MC KIR KI Australian dollar Nauru MC NRU NR Australian dollar Norfolk Island MC NFK NF Australian dollar Tuvalu MC TUV TV Australian dollar Bahamas MC / VI BHS BS Bahamian dollar Bahrain MC / VI BHR BH Bahraini dinar Bangladesh MC / VI BGD BD Taka Armenia VI ARM AM Armenian Dram Barbados MC / VI BRB BB Barbados dollar Bermuda MC / VI BMU BM Bermudian dollar Bolivia, MC / VI BOL BO Boliviano Plurinational State of Botswana MC / VI BWA BW Pula Belize MC / VI BLZ BZ Belize dollar Solomon Islands MC / VI SLB SB Solomon Islands dollar Brunei Darussalam MC / VI BRN BN Brunei dollar Myanmar MC / VI MMR MM Myanmar kyat (effective 1 November 2012) Burundi MC / VI BDI BI Burundi franc Cambodia MC / VI KHM KH Riel Canada MC / VI CAN CA Canadian dollar Cape Verde MC / VI CPV CV Cape Verde escudo Cayman Islands MC / VI CYM KY Cayman Islands dollar Sri Lanka MC / VI LKA LK Sri Lanka rupee Chile MC / VI CHL CL Chilean peso China VI CHN CN Colombia MC / VI COL CO Colombian peso Comoros MC / VI COM KM Comoro franc Costa Rica MC / VI CRI CR Costa Rican colony Croatia MC / VI HRV HR Kuna Cuba VI Czech Republic MC / VI CZE CZ Koruna Denmark MC / VI DNK DK Danish krone Faeroe Is. -

International Currency Codes

Country Capital Currency Name Code Afghanistan Kabul Afghanistan Afghani AFN Albania Tirana Albanian Lek ALL Algeria Algiers Algerian Dinar DZD American Samoa Pago Pago US Dollar USD Andorra Andorra Euro EUR Angola Luanda Angolan Kwanza AOA Anguilla The Valley East Caribbean Dollar XCD Antarctica None East Caribbean Dollar XCD Antigua and Barbuda St. Johns East Caribbean Dollar XCD Argentina Buenos Aires Argentine Peso ARS Armenia Yerevan Armenian Dram AMD Aruba Oranjestad Aruban Guilder AWG Australia Canberra Australian Dollar AUD Austria Vienna Euro EUR Azerbaijan Baku Azerbaijan New Manat AZN Bahamas Nassau Bahamian Dollar BSD Bahrain Al-Manamah Bahraini Dinar BHD Bangladesh Dhaka Bangladeshi Taka BDT Barbados Bridgetown Barbados Dollar BBD Belarus Minsk Belarussian Ruble BYR Belgium Brussels Euro EUR Belize Belmopan Belize Dollar BZD Benin Porto-Novo CFA Franc BCEAO XOF Bermuda Hamilton Bermudian Dollar BMD Bhutan Thimphu Bhutan Ngultrum BTN Bolivia La Paz Boliviano BOB Bosnia-Herzegovina Sarajevo Marka BAM Botswana Gaborone Botswana Pula BWP Bouvet Island None Norwegian Krone NOK Brazil Brasilia Brazilian Real BRL British Indian Ocean Territory None US Dollar USD Bandar Seri Brunei Darussalam Begawan Brunei Dollar BND Bulgaria Sofia Bulgarian Lev BGN Burkina Faso Ouagadougou CFA Franc BCEAO XOF Burundi Bujumbura Burundi Franc BIF Cambodia Phnom Penh Kampuchean Riel KHR Cameroon Yaounde CFA Franc BEAC XAF Canada Ottawa Canadian Dollar CAD Cape Verde Praia Cape Verde Escudo CVE Cayman Islands Georgetown Cayman Islands Dollar KYD _____________________________________________________________________________________________ -

Chile and the Falklands Wildlife Holiday

14 days 10:33 01-09-2021 We are the UK’s No.1 specialist in travel to Latin As our name suggests, we are single-minded America and have been creating award-winning about Latin America. This is what sets us apart holidays to every corner of the region for over four from other travel companies – and what allows us decades; we pride ourselves on being the most to offer you not just a holiday but the opportunity to knowledgeable people there are when it comes to experience something extraordinary on inspiring travel to Central and South America and journeys throughout Mexico, Central and South passionate about it too. America. A passion for the region runs Fully bonded and licensed Our insider knowledge helps through all we do you go beyond the guidebooks ATOL-protected All our Consultants have lived or We hand-pick hotels with travelled extensively in Latin On your side when it matters character and the most America rewarding excursions Book with confidence, knowing Up-to-the-minute knowledge every penny is secure Let us show you the Latin underpinned by 40 years' America we know and love experience 10:33 01-09-2021 10:33 01-09-2021 Most travellers to the Falklands visit for only a day or two as part of a cruise. Our holiday includes a whole week discovering the highlights of the islands. We’ll take you to Port Stanley, the capital, which looks like a small English town fifty years ago. The remains of ships abandoned 100 years ago are still to be seen in the coves, testament to an era when the islands were a safe haven when all ships passed this way before the Panama Canal opened. -

Simon REEVE Griff Rhys Jones

COMPASS by COX & KINGS TRAVEL TRAVEL & KINGS COX by COMPASS Griff Rhys Jones In Petra PEnguin CLASSiCS Falklands’ wildlife New culinary holidays – with the experts Holidays featuring former MasterChef MasterChef Travel is an inspiring new collection of culinary holidays, revealing contestants in 2014 the wonders of the world’s great food destinations in the company of experts Andrew ‘Koj’ Kojima – Thailand Simon REEVE and fellow food lovers. Masterchef Travel holidays are not competitive – they Ash Mair – Spain are an opportunity to spend time with local experts who share their passion for Dhruv Baker – India & Mexico cooking and provide an authentic understanding of their region’s cuisine. The “I’m ridiculously lucky” James Nathan – Vietnam holidays also include plenty of time for exploring many of the countries’ most Keri Moss – Turkey & Morocco captivating sights. Larkin Cen – China A number of holidays also feature MasterChef personalities and on the right is Sara Danesin Medio – Italy LET’S DRIVE a list of former MasterChef contestants who will be taking part in trips in 2014 and the destinations where you can join them. Coastal Canada MasterChef Travel tours are superb value, with prices starting from just £995 per person for the 4-night Inspiring Istanbul. For full details, visit mastercheftravel.com or call 020 7873 5005 Ash Mair SPRING 2014 SPRING MasterChef Travel © Shine Limited Licensed by Shine 360° Operated by Cox & Kings Travel Limited travel news • reviews • interviews R&J A4 ad revised_Layout 1 27/02/2014 17:56 Page 1 “AN UNMISSABLE EVENT” THE DAILY TELEGRAPH RAYMOND GUBBAY AND THE ROYAL ALBERT HALL PRESENT My Magnifique Voyages English National Ballet Derek Deane’s breathtaking production ROMEO &JULIET staged in-the-round Principal casting includes Carlos Acosta & Tamara Rojo Vadim Muntagirov & Daria Klimentová Friedemann Vogel & Alina Cojocaru For Principal casting information, view website for details. -

FAO Country Name ISO Currency Code* Currency Name*

FAO Country Name ISO Currency Code* Currency Name* Afghanistan AFA Afghani Albania ALL Lek Algeria DZD Algerian Dinar Amer Samoa USD US Dollar Andorra ADP Andorran Peseta Angola AON New Kwanza Anguilla XCD East Caribbean Dollar Antigua Barb XCD East Caribbean Dollar Argentina ARS Argentine Peso Armenia AMD Armeniam Dram Aruba AWG Aruban Guilder Australia AUD Australian Dollar Austria ATS Schilling Azerbaijan AZM Azerbaijanian Manat Bahamas BSD Bahamian Dollar Bahrain BHD Bahraini Dinar Bangladesh BDT Taka Barbados BBD Barbados Dollar Belarus BYB Belarussian Ruble Belgium BEF Belgian Franc Belize BZD Belize Dollar Benin XOF CFA Franc Bermuda BMD Bermudian Dollar Bhutan BTN Ngultrum Bolivia BOB Boliviano Botswana BWP Pula Br Ind Oc Tr USD US Dollar Br Virgin Is USD US Dollar Brazil BRL Brazilian Real Brunei Darsm BND Brunei Dollar Bulgaria BGN New Lev Burkina Faso XOF CFA Franc Burundi BIF Burundi Franc Côte dIvoire XOF CFA Franc Cambodia KHR Riel Cameroon XAF CFA Franc Canada CAD Canadian Dollar Cape Verde CVE Cape Verde Escudo Cayman Is KYD Cayman Islands Dollar Cent Afr Rep XAF CFA Franc Chad XAF CFA Franc Channel Is GBP Pound Sterling Chile CLP Chilean Peso China CNY Yuan Renminbi China, Macao MOP Pataca China,H.Kong HKD Hong Kong Dollar China,Taiwan TWD New Taiwan Dollar Christmas Is AUD Australian Dollar Cocos Is AUD Australian Dollar Colombia COP Colombian Peso Comoros KMF Comoro Franc FAO Country Name ISO Currency Code* Currency Name* Congo Dem R CDF Franc Congolais Congo Rep XAF CFA Franc Cook Is NZD New Zealand Dollar Costa Rica -

List of Currencies of All Countries

The CSS Point List Of Currencies Of All Countries Country Currency ISO-4217 A Afghanistan Afghan afghani AFN Albania Albanian lek ALL Algeria Algerian dinar DZD Andorra European euro EUR Angola Angolan kwanza AOA Anguilla East Caribbean dollar XCD Antigua and Barbuda East Caribbean dollar XCD Argentina Argentine peso ARS Armenia Armenian dram AMD Aruba Aruban florin AWG Australia Australian dollar AUD Austria European euro EUR Azerbaijan Azerbaijani manat AZN B Bahamas Bahamian dollar BSD Bahrain Bahraini dinar BHD Bangladesh Bangladeshi taka BDT Barbados Barbadian dollar BBD Belarus Belarusian ruble BYR Belgium European euro EUR Belize Belize dollar BZD Benin West African CFA franc XOF Bhutan Bhutanese ngultrum BTN Bolivia Bolivian boliviano BOB Bosnia-Herzegovina Bosnia and Herzegovina konvertibilna marka BAM Botswana Botswana pula BWP 1 www.thecsspoint.com www.facebook.com/thecsspointOfficial The CSS Point Brazil Brazilian real BRL Brunei Brunei dollar BND Bulgaria Bulgarian lev BGN Burkina Faso West African CFA franc XOF Burundi Burundi franc BIF C Cambodia Cambodian riel KHR Cameroon Central African CFA franc XAF Canada Canadian dollar CAD Cape Verde Cape Verdean escudo CVE Cayman Islands Cayman Islands dollar KYD Central African Republic Central African CFA franc XAF Chad Central African CFA franc XAF Chile Chilean peso CLP China Chinese renminbi CNY Colombia Colombian peso COP Comoros Comorian franc KMF Congo Central African CFA franc XAF Congo, Democratic Republic Congolese franc CDF Costa Rica Costa Rican colon CRC Côte d'Ivoire West African CFA franc XOF Croatia Croatian kuna HRK Cuba Cuban peso CUC Cyprus European euro EUR Czech Republic Czech koruna CZK D Denmark Danish krone DKK Djibouti Djiboutian franc DJF Dominica East Caribbean dollar XCD 2 www.thecsspoint.com www.facebook.com/thecsspointOfficial The CSS Point Dominican Republic Dominican peso DOP E East Timor uses the U.S. -

Exchange Rate Statistics January 2017

Exchange rate statistics January 2017 Statistical Supplement 5 to the Monthly Report Deutsche Bundesbank Exchange rate statistics January 2017 2 Deutsche Bundesbank Wilhelm-Epstein-Strasse 14 60431 Frankfurt am Main Germany Postal address Postfach 10 06 02 60006 Frankfurt am Main Germany Tel +49 69 9566-0 or +49 69 9566 8604 Fax +49 69 9566 8606 or 3077 The Statistical Supplement Exchange rate statistics is published by the Deutsche Bundesbank, Frankfurt am http://www.bundesbank.de Main, by virtue of section 18 of the Bundesbank Act. It is available to interested parties free of charge. Reproduction permitted only if source is stated. Further statistical data, supplementing the Monthly Report, The German-language version of the Statis tical Supple- can be found in the follow ing supplements. ment Exchange rate statistics is published quarterly in printed form. The Deutsche Bundesbank also publishes an Banking statistics monthly updated monthly edition in German and in English on its Capital market statistics monthly website. In cases of doubt, the original German-language Balance of payments statistics monthly version is the sole authoritative text. Seasonally adjusted business statistics monthly ISSN 2190–8990 (online edition) Selected updated statistics are also available on the Cut-off date: 10 January 2017. website. Deutsche Bundesbank Exchange rate statistics January 2017 3 Contents I Euro area and exchange rate stability convergence criterion 1 Euro-area member states and irrevoc able euro conversion rates in the third stage of European Economic and Monetary Union .................................................................. 7 2 Central rates and intervention rates in Exchange Rate Mechanism II ............................... 7 II Euro foreign exchange reference rates of the European Central Bank 1 Daily rates . -

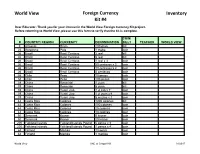

World View Foreign Currency Kit #4 Inventory

World View Foreign Currency Inventory Kit #4 Dear Educator: Thank you for your interest in the World View Foreign Currency Kit project. Before returning to World View, please use this form to verify that the kit is complete. COIN/ # COUNTRY/ REGION CURRENCY DENOMINATION BILL? TEACHER WORLD VIEW 9 Armenia Dram 200 dram bill 25 Botswana Pula 1 thebe coin 26 Brazil Real/ Centavo 2 real bill 26 Brazil Real/ Centavo 5 real bill 26 Brazil Real/ Centavo 1 real x 3 coin 26 Brazil Real/ Centavo 50 centavos x 2 coin 26 Brazil Real/ Centavo 10 centavos x 2 coin 26 Brazil Real/ Centavo 5 centavos coin 38 Chile Peso 10 pesos coin 38 Chile Peso 100 pesos coin 39 China Renminbi 1 yuan bill 39 China Renminbi 5 yuan bill 39 China Yuan/ Jiao 1 yi jiao x 7 coin 39 China Yuan/ Jiao 1 yi yuan x 6 coin 39 China Yuan/ Jiao 5 wu jiao x 2 coin 44 Costa Rica Colones 1000 colones bill 44 Costa Rica Colones 100 colones coin 44 Costa Rica Colones 25 colones coin 44 Costa Rica Colones 10 colones coin 50 Denmark Kroner 5 kroner coin 50 Denmark Kroner 20 kroner coin 200 Falkland Islands Falkland Islands Pound 5 pence x 3 coin 200 Falkland Islands Falkland Islands Pound 1 pence x 4 coin 64 Finland Markka 10 penni coin 64 Finland Markka 1 markka coin World View UNC at Chapel Hill 01/2017 World View Foreign Currency Inventory Kit #4 69 Germany Deutsche Mark 10 Deutsche mark bill 80 Hungary Forint 20 forint coin 80 Hungary Forint 100 forint coin 80 Hungary Forint 5 forint coin 92 Japan Yen 1 yen x 2 coin 92 Japan Yen 10 yen coin 92 Japan Yen 100 yen x 2 coin 92 Japan Yen -

Introduction

South Georgia-plan for progress 9/27/06 5:48 PM Page 8 Salvesen Range from Drygalski Fjord David Nicholls South Georgia-plan for progress 9/27/06 5:48 PM Page 1 Introduction Aims and purpose of the plan This current Plan is not intended to replace the 2000 version, but to complement it. The policies have been updated and are presented in a readable and The Environmental Management Plan accessible format with clear commitments and for South Georgia, published in 2000, objectives. It is set out in seven chapters comprising gives comprehensive background an introduction and sections on natural environ- ment, heritage, visiting South Georgia, human information on the islands and sets impacts, fisheries and research. Each chapter con- out management policies. The tains articles and feature boxes, with a focus on intention was to review these recent activities designed to provide accessible background information to the policies. The policies policies after a period of five years. are presented at the end of each chapter. During 2005, a review was undertaken taking into consideration information gathered since the last South Georgia – at a glance Plan was produced, including Government com- missioned environmental reports. A comprehen- South Georgia is a long, narrow island situated in sive questionnaire survey was undertaken to the rough and windswept Southern Ocean. engage stakeholders in the policy revisions. The Spectacular mountains rise from the sea to almost revised policies are presented in this Plan. 3000m, forming a central ridge running from The Plan is intended to cover the five year period north-west to south-east. -

Swift Currency Codes

Balance of Payments Reporting System 1 SECTION C.4 SWIFT CURRENCY AND COUNTRY CODES COUNTRY CURRENCY CURRENCY COUNTRY CODE CODE Afghanistan Afghani AFA AF Albania Lek ALL AL Algeria Algerian Dinar DZD DZ American Samoa US Dollar USD AS Andorra Andorran Peseta ADP AD Andorra Spanish Peseta ESP AD Andorra French Franc FRF AD Angola New Kwanza AON AO Angola Kwanza Reajustado AOR AO Anguilla East Carribean Dollar XCD AI Antigua and Barbuda East Carribean Dollar XCD AG Argentina Argentine Peso ARS AR Armenia Armenian Dram AMD AM Aruba Aruban Guilder AWG AW Australia Australian Dollar AUD AU Austria Schilling ATS AT Austria Euro EUR AT Azerbaijan Azerbaijanian Manat AZM AZ Bahamas Bahamian Dollar BSD BS Bahrain Bahraini Dinar BHD BH Bangladesh Taka BDT BD Barbados Barbados Dollar BBD BB Belarus Belarussian Ruble BYB BY Belarus Belarussian Ruble (new) BYR BY Belgium Belgian Franc BEF BE Belgium Euro EUR BE Belize Belize Dollar BZD BZ Benin CFA Franc BCEAO XOF BJ Bermuda Bermudian Dollar BMD BM Bhutan Ngultrum BTN BT Bhutan Indian Rupee INR BT Bolivia Boliviano BOB BO Bolivia Mvdol BOV BO Bosnia and Herzegovina Convertible Marks BAM BA Botswana Pula BWP BW Bouvet Island Norwegian Krone NOK BV Brazil Brazilian Real BRL BR British Indian Ocean US Dollar USD IO Territory Brunei Darussalam Burnei Dollar BND BN Bulgaria Lev BGL BG Bulgaria Bulgarian Lev BGN BG Burkina Faso CFA Franc BCEAO XOF BF Burundi Burundi Franc BIF BI Operations manual (Customer transaction reporting) 1 November 2001 Balance of Payments Reporting System 2 SECTION C.4 COUNTRY -

PDF External Sector Statistics ISO Country Codes

External Sector Statistics (ESS) System - Submission of International Transactions Page 285 of 300 and External Position Information APPENDIX 8 STANDARD CODES Appendix 8(a) List of Country and Currency Codes ISO Country and Currency Codes* Country Code Currency Code AFGHANISTAN AF Afghani AFN ÅLAND ISLANDS AX Euro EUR ALBANIA AL Lek ALL ALGERIA DZ Algerian Dinar DZD AMERICAN SAMOA AS US Dollar USD ANDORRA AD Euro EUR ANGOLA AO Kwanza AOA ANGUILLA AI East Caribbean Dollar XCD ANTARCTICA AQ No universal currency ANTIGUA AND BARBUDA AG East Caribbean Dollar XCD ARGENTINA AR Argentine Peso ARS ARMENIA AM Armenian Dram AMD ARUBA AW Aruban Florin AWG AUSTRALIA AU Australian Dollar AUD AUSTRIA AT Euro EUR AZERBAIJAN AZ Azerbaijanian Manat AZN BAHAMAS BS Bahamian Dollar BSD BAHRAIN BH Bahraini Dinar BHD BANGLADESH BD Taka BDT BARBADOS BB Barbados Dollar BBD BELARUS BY Belarussian Ruble BYR BELGIUM BE Euro EUR BELIZE BZ Belize Dollar BZD BENIN BJ CFA Franc BCEAO XOF BERMUDA BM Bermudian Dollar BMD BHUTAN BT Ngultrum BTN BHUTAN BT Indian Rupee INR BOLIVIA, PLURINATIONAL STATE OF BO Boliviano BOB BOLIVIA, PLURINATIONAL STATE OF BO Mvdol BOV BONAIRE, SINT EUSTATIUS AND SABA BQ US Dollar USD BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA BA Convertible Mark BAM BOTSWANA BW Pula BWP BOUVET ISLAND BV Norwegian Krone NOK BRAZIL BR Brazilian Real BRL BRITISH INDIAN OCEAN TERRITORY IO US Dollar USD BRUNEI DARUSSALAM BN Brunei Dollar BND BULGARIA BG Bulgarian Lev BGN BURKINA FASO BF CFA Franc BCEAO XOF BURUNDI BI Burundi Franc BIF CAMBODIA KH Riel KHR CAMEROON CM CFA Franc BEAC