Bel Canto Technique

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’S Opera and Concert Arias Joshua M

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 10-3-2014 The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias Joshua M. May University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation May, Joshua M., "The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias" (2014). Doctoral Dissertations. 580. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/580 ABSTRACT The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias Joshua Michael May University of Connecticut, 2014 W. A. Mozart’s opera and concert arias for tenor are among the first music written specifically for this voice type as it is understood today, and they form an essential pillar of the pedagogy and repertoire for the modern tenor voice. Yet while the opera arias have received a great deal of attention from scholars of the vocal literature, the concert arias have been comparatively overlooked; they are neglected also in relation to their counterparts for soprano, about which a great deal has been written. There has been some pedagogical discussion of the tenor concert arias in relation to the correction of vocal faults, but otherwise they have received little scrutiny. This is surprising, not least because in most cases Mozart’s concert arias were composed for singers with whom he also worked in the opera house, and Mozart always paid close attention to the particular capabilities of the musicians for whom he wrote: these arias offer us unusually intimate insights into how a first-rank composer explored and shaped the potential of the newly-emerging voice type of the modern tenor voice. -

Falsetto Head Voice Tips to Develop Head Voice

Volume 1 Issue 27 September 04, 2012 Mike Blackwood, Bill Wiard, Editors CALENDAR Current Songs (Not necessarily “new”) Goodnight Sweetheart, Goodnight Spiritual Medley Home on the Range You Raise Me Up Just in Time Question: What’s the difference between head voice and falsetto? (Contunued) Answer: Falsetto Notice the word "falsetto" contains the word "false!" That's exactly what it is - a false impression of the female voice. This occurs when a man who is naturally a baritone or bass attempts to imitate a female's voice. The sound is usually higher pitched than the singer's normal singing voice. The falsetto tone produced has a head voice type quality, but is not head voice. Falsetto is the lightest form of vocal production that the human voice can make. It has limited strength, tones, and dynamics. Oftentimes when singing falsetto, your voice may break, jump, or have an airy sound because the vocal cords are not completely closed. Head Voice Head voice is singing in which the upper range of the voice is used. It's a natural high pitch that flows evenly and completely. It's called head voice or "head register" because the singer actually feels the vibrations of the sung notes in their head. When singing in head voice, the vocal cords are closed and the voice tone is pure. The singer is able to choose any dynamic level he wants while singing. Unlike falsetto, head voice gives a connected sound and creates a smoother harmony. Tips to Develop Head Voice If you want to have a smooth tone and develop a head voice singing talent, you can practice closing the gap with breathing techniques on every note. -

1 Making the Clarinet Sing

Making the Clarinet Sing: Enhancing Clarinet Tone, Breathing, and Phrase Nuance through Voice Pedagogy D.M.A Document Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Alyssa Rose Powell, M.M. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2020 D.M.A. Document Committee Dr. Caroline A. Hartig, Advisor Dr. Scott McCoy Dr. Eugenia Costa-Giomi Professor Katherine Borst Jones 1 Copyrighted by Alyssa Rose Powell 2020 2 Abstract The clarinet has been favorably compared to the human singing voice since its invention and continues to be sought after for its expressive, singing qualities. How is the clarinet like the human singing voice? What facets of singing do clarinetists strive to imitate? Can voice pedagogy inform clarinet playing to improve technique and artistry? This study begins with a brief historical investigation into the origins of modern voice technique, bel canto, and highlights the way it influenced the development of the clarinet. Bel canto set the standards for tone, expression, and pedagogy in classical western singing which was reflected in the clarinet tradition a hundred years later. Present day clarinetists still use bel canto principles, implying the potential relevance of other facets of modern voice pedagogy. Singing techniques for breathing, tone conceptualization, registration, and timbral nuance are explored along with their possible relevance to clarinet performance. The singer ‘in action’ is presented through an analysis of the phrasing used by Maria Callas in a portion of ‘Donde lieta’ from Puccini’s La Bohème. This demonstrates the influence of text on interpretation for singers. -

A Guide to Vibrato & Straight Tone

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 9-2016 The Versatile Singer: A Guide to Vibrato & Straight Tone Danya Katok The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/1394 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] THE VERSATILE SINGER: A GUIDE TO VIBRATO & STRAIGHT TONE by DANYA KATOK A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts, The City University of New York 2016 ©2016 Danya Katok All rights reserved ii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Music to satisfy the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Date L. Poundie Burstein Chair of the Examining Committee Date Norman Carey Executive Officer Philip Ewell, advisor Loralee Songer, first reader Stephanie Jensen-Moulton L. Poundie Burstein Supervisory Committee THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii Abstract THE VERSATILE SINGER: A GUIDE TO VIBRATO & STRAIGHT TONE by Danya Katok Advisor: Philip Ewell Straight tone is a valuable tool that can be used by singers of any style to both improve technical ideals, such as resonance and focus, and provide a starting point for transforming the voice to meet the stylistic demands of any genre. -

Bel Canto: the Teaching of the Classical Italian Song-Schools, Its Decline and Restoration

Performance Practice Review Volume 3 Article 9 Number 1 Spring "Bel canto: The eT aching of the Classical Italian Song-Schools, Its Decline and Restoration" By Lucie Manén Philip Lieson Miller Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr Part of the Music Practice Commons Miller, Philip Lieson (1990) ""Bel canto: The eT aching of the Classical Italian Song-Schools, Its Decline and Restoration" By Lucie Manén," Performance Practice Review: Vol. 3: No. 1, Article 9. DOI: 10.5642/perfpr.199003.01.9 Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr/vol3/iss1/9 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Claremont at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Performance Practice Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Reviews 97 Lucie Manen. Bel canto; The Teaching of the Classical Italian Song- Schools, Its Decline and Restoration. New York: Oxford University Press, 1987. bibliography, 75p. Bel canto, it is generally agreed, is a lost art. But what, precisely, was bel canto? The word is used to describe the singing of the great castrati, and the repertory of classic Italian airs is known as bel canto music; the term conies up again to cover the operas of Rossini, Donizetti, and Bellini and the school of singers trained to sing them. But Philip A. Duey, in his study of the subject, states: "The term Bel Canto does not appear as such during the period with which it is most often associated, i.e., the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries; this may be said with finality." Lucie Manen as a singer was a casualty of World War II. -

Of Gods and Monsters: Signification in Franz Waxman's Film Score Bride of Frankenstein

This is a repository copy of Of Gods and Monsters: Signification in Franz Waxman’s film score Bride of Frankenstein. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/118268/ Version: Accepted Version Article: McClelland, C (Cover date: 2014) Of Gods and Monsters: Signification in Franz Waxman’s film score Bride of Frankenstein. Journal of Film Music, 7 (1). pp. 5-19. ISSN 1087-7142 https://doi.org/10.1558/jfm.27224 © Copyright the International Film Music Society, published by Equinox Publishing Ltd 2017, This is an author produced version of a paper published in the Journal of Film Music. Uploaded in accordance with the publisher's self-archiving policy. Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Paper for the Journal of Film Music Of Gods and Monsters: Signification in Franz Waxman’s film score Bride of Frankenstein Universal’s horror classic Bride of Frankenstein (1935) directed by James Whale is iconic not just because of its enduring images and acting, but also because of the high quality of its score by Franz Waxman. -

12-04-2018 Traviata Eve.Indd

GIUSEPPE VERDI la traviata conductor Opera in three acts Yannick Nézet-Séguin Libretto by Francesco Maria Piave, production Michael Mayer based on the play La Dame aux Camélias by Alexandre Dumas fils set designer Christine Jones Tuesday, December 4, 2018 costume designer 8:00–11:00 PM Susan Hilferty lighting designer New Production Premiere Kevin Adams choreographer Lorin Latarro DEBUT The production of La Traviata was made possible by a generous gift from The Paiko Foundation Major additional funding for this production was received from Mercedes T. Bass, Mr. and Mrs. Paul M. Montrone, and Rolex general manager Peter Gelb jeanette lerman-neubauer music director Yannick Nézet-Séguin 2018–19 SEASON The 1,012th Metropolitan Opera performance of GIUSEPPE VERDI’S la traviata conductor Yannick Nézet-Séguin in order of vocal appearance violet ta valéry annina Diana Damrau Maria Zifchak flor a bervoix giuseppe Kirstin Chávez Marco Antonio Jordão the marquis d’obigny giorgio germont Jeongcheol Cha Quinn Kelsey baron douphol a messenger Dwayne Croft* Ross Benoliel dr. grenvil Kevin Short germont’s daughter Selin Sahbazoglu gastone solo dancers Scott Scully Garen Scribner This performance Martha Nichols is being broadcast live on Metropolitan alfredo germont Opera Radio on Juan Diego Flórez SiriusXM channel 75 and streamed at metopera.org. Tuesday, December 4, 2018, 8:00–11:00PM MARTY SOHL / MET OPERA Diana Damrau Chorus Master Donald Palumbo as Violetta and Musical Preparation John Keenan, Yelena Kurdina, Juan Diego Flórez Liora Maurer, and Jonathan -

The KF International Marcella Sembrich International Voice

The KF is excited to announce the winners of the 2015 Marcella Sembrich International Voice Competition: 1st prize – Jakub Jozef Orlinski, counter-tenor; 2nd prize – Piotr Buszewski, tenor; 3rd prize – Katharine Dain, soprano; Honorable Mention – Marcelina Beucher, soprano; Out of 92 applicants, 37 contestants took part in the preliminary round of the competition on Saturday, November 7th, with 9 progressing into the final round on Sunday, November 8th at Ida K. Lang Recital Hall at Hunter College. This year's competition was evaluated by an exceptional jury: Charles Kellis (Juilliard, Prof. emeritus) served as Chairman of the Jury, joined by Damon Bristo (Vice President and Artist Manager at Columbia Artists Management Inc.), Markus Beam (Artist Manager at IMG Artists) and Dr. Malgorzata Kellis who served as a Creative Director and Polish song expert. About the KF's Marcella Sembrich Competition: Marcella Sembrich-Kochanska, soprano (1858-1935) was one of Poland's greatest opera stars. She appeared during the first season of the Metropolitan Opera in 1883, and would go on to sing in over 450 performances at the Met. Her portrait can be found at the Metropolitan Opera House, amongst the likes of Luciano Pavarotti, Placido Domingo, and Giuseppe Verdi. The KF's Marcella Sembrich Memorial Voice Competition honors the memory of this great Polish artist, with the aim of popularizing Polish song in the United States, and discovering new talents (aged 18-35) in the operatic world. This year the competition has turned out to be very successful, considering that the number of contestants have greatly increased and that we have now also attracted a number of International contestants from Japan, China, South Korea, France, Canada, Puerto Rico and Poland. -

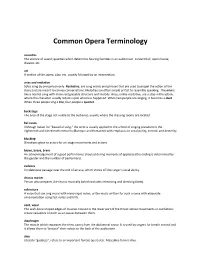

Common Opera Terminology

Common Opera Terminology acoustics The science of sound; qualities which determine hearing facilities in an auditorium, concert hall, opera house, theater, etc. act A section of the opera, play, etc. usually followed by an intermission. arias and recitative Solos sung by one person only. Recitative, are sung words and phrases that are used to propel the action of the story and are meant to convey conversations. Melodies are often simple or fast to resemble speaking. The aria is like a normal song with more recognizable structure and melody. Arias, unlike recitative, are a stop in the action, where the character usually reflects upon what has happened. When two people are singing, it becomes a duet. When three people sing a trio, four people a quartet. backstage The area of the stage not visible to the audience, usually where the dressing rooms are located. bel canto Although Italian for “beautiful song,” the term is usually applied to the school of singing prevalent in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries (Baroque and Romantic) with emphasis on vocal purity, control, and dexterity blocking Directions given to actors for on-stage movements and actions bravo, brava, bravi An acknowledgement of a good performance shouted during moments of applause (the ending is determined by the gender and the number of performers). cadenza An elaborate passage near the end of an aria, which shows off the singer’s vocal ability. chorus master Person who prepares the chorus musically (which includes rehearsing and directing them). coloratura A voice that can sing music with many rapid notes, or the music written for such a voice with elaborate ornamentation using fast notes and trills. -

ELIJAH, Op. 70 (1846) Libretto: Julius Schubring English Translation

ELIJAH, Op. 70 (1846) Libretto: Julius Schubring Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy (1809-1847) English Translation: William Bartholomew PART ONE The Biblical tale of Elijah dates from c. 800 BCE. "In fact I imagined Elijah as a real prophet The core narrative is found in the Book of Kings through and through, of the kind we could (I and II), with minor references elsewhere in really do with today: Strong, zealous and, yes, the Hebrew Bible. The Haggadah supplements even bad-tempered, angry and brooding — in the scriptural account with a number of colorful contrast to the riff-raff, whether of the court or legends about the prophet’s life and works. the people, and indeed in contrast to almost the After Moses, Abraham and David, Elijah is the whole world — and yet borne aloft as if on Old Testament character mentioned most in the angels' wings." – Felix Mendelssohn, 1838 (letter New Testament. The Qu’uran also numbers to Julius Schubring, Elijah’s librettist) Elijah (Ilyas) among the major prophets of Islam. Elijah’s name is commonly translated to mean “Yahweh is my God.” PROLOGUE: Elijah’s Curse Introduction: Recitative — Elijah Elijah materializes before Ahab, king of the Four dark-hued chords spring out of nowhere, As God the Lord of Israel liveth, before Israelites, to deliver a bitter curse: Three years of grippingly setting the stage for confrontation.1 whom I stand: There shall not be dew drought as punishment for the apostasy of Ahab With the opening sentence, Mendelssohn nor rain these years, but according to and his court. The prophet’s appearance is a introduces two major musical motives that will my word. -

The Application of Bel Canto Concepts and Principles to Trumpet Pedagogy and Performance

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1980 The Application of Bel Canto Concepts and Principles to Trumpet Pedagogy and Performance. Malcolm Eugene Beauchamp Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Beauchamp, Malcolm Eugene, "The Application of Bel Canto Concepts and Principles to Trumpet Pedagogy and Performance." (1980). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 3474. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/3474 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. -

Nini, Bloodshed, and La Marescialla D'ancre

28 Nini, bloodshed, and La marescialla d’Ancre Alexander Weatherson (This article originally appeared in Donizetti Society Newsletter 88 (February 2003)) An odd advocate of so much operatic blood and tears, the mild Alessandro Nini was born in the calm of Fano on 1 November 1805, an extraordinary centre section of his musical life was to be given to the stage, the rest of it to the church. It would not be too disrespectful to describe his life as a kind of sandwich - between two pastoral layers was a filling consisting of some of the most bloodthirsty operas ever conceived. Maybe the excesses of one encouraged the seclusion of the other? He began his strange career with diffidence - drawn to religion his first steps were tentative, devoted attendance on the local priest then, fascinated by religious music - study with a local maestro, then belated admission to the Liceo Musicale di Bologna (1827) while holding appointments as Maestro di Cappella at churches in Montenovo and Ancona; this stint capped,somewhat surprisingly - between 1830 and 1837 - by a spell in St. Petersburg teaching singing. Only on his return to Italy in his early thirties did he begin composing in earnest. Was it Russia that introduced him to violence? His first operatic project - a student affair - had been innocuous enough, Clato, written at Bologna with an milk-and-water plot based on Ossian (some fragments remain), all the rest of his operas appeared between 1837 and 1847, with one exception. The list is as follows: Ida della Torre (poem by Beltrame) Venice 1837; La marescialla d’Ancre (Prati) Padua 1839; Christina di Svezia (Cammarano/Sacchero) Genova 1840; Margarita di Yorck [sic] (Sacchero) Venice 1841; Odalisa (Sacchero) Milano 1842; Virginia (Bancalari) Genova 1843, and Il corsaro (Sacchero) Torino 1847.