Shakespeare's Birthday Party

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

OCTOBER 2019 Nickolas Grace Wayne Sleep OBE

President: Vice President: No. 508 - OCTOBER 2019 Nickolas Grace Wayne Sleep OBE Vic-Wells News If you are on Instagram, please follow us at @vicwells, where you can like and comment on the posts which include news about the VWs and upcoming events at the Old Vic and Sadler’s Wells. We would love to hear from you about your own personal favourites. Pictured here, in a new posting, is our Vice-President, Wayne Sleep with Freddie Mercury and Elton John. Did you know, Freddie Mercury danced for the Royal Ballet? He performed in specially choreographed versions of Bohemian Rhapsody and Crazy Little Thing Called Love at a charity gala in 1979. A few years later, as a kind of cultural exchange, the Royal Ballet danced for Freddie Mercury, in the video for Queen's I Want to Break Free. The Merry Wives of Windsor Our very own Liz Schafer will be giving a talk at a Study Day at Shakespeare’s Globe - a day of talks, workshops, seminars and lively discussion on The Merry Wives of Windsor. This is an opportunity to meet like-minded audience members and explore the key themes and interpretations in the play with Globe artists and leading Shakespeare scholars. Professor Liz Schafer will run a session on 'How to become a Merry Wife and Influence People'. She will explore how the shrewd women in the play are able to be both merry and honest as well as disciplining the wayward men that surround them. Nickolas Grace Over the summer VWs President Nickolas Grace and Una Stubbs performed together as part of the Gillian Lynne Memorial at the West End Theatre named after her. -

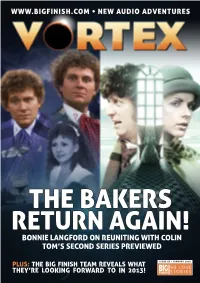

The Bakers Return Again! Bonnie Langford on Reuniting with Colin Tom’S Second Series Previewed

WWW.BIGFINISH.COM • NEW AUDIO ADVENTURES THE BAKERS RETURN AGAIN! BONNIE LANGFORD ON REUNITING WITH COLIN TOM’S SECOND SERIES PREVIEWED PLUS: THE BIG FINISH TEAM REVEALS WHAT ISSUE 47 • JANUARY 2013 THEY’RE LOOKING FORWARD TO IN 2013! VORTEX MAGAZINE | PAGE 1 VORTEX MAGAZINE | PAGE 2 SNEAK PREVIEWS EDITORIAL AND WHISPERS s the year begins, I’d just like to welcome aboard all those of you who have dipped your toes into the Big Finish A audio pool (or other such terrible metaphors) after coming on board in the wave of enthusiasm for Dark Eyes, featuring the return of Paul McGann as the Eighth Doctor (in a leather jacket!!!) and the arrival of his brand new assistant Molly O’Sullivan (played by the rather brilliant Ruth Bradley). Some of you have also come on board via our 12 Days of Christmas special offer on the website, when we went completely bonkers and offered up some really great stuff for just £2.99 per download for 48 hours only. So… if you’re on board, please do feel free to stay with us for the rest of our voyage. This year, we hope to build on the successes of last year. There will, of course, be a follow-up to Dark Eyes… in fact, there will be more than one follow-up. And carrying on from the great JAGO AND LITEFOOT SERIES FIVE success of our first series of Tom Baker Fourth Doctor stories, we commence our second series this month, with the late, lovely and change of scenery for series five, as very much lamented Mary Tamm as Romana. -

The Scottish Arts Council, a Ne W Great Britain'

k~rcAA/~ d e cc" ARTS COUNCIL OF GREAT BRITAI N REFERENCE ONLY DO NOT REMOVE .FROM THE LIBRARY The Arts Council of Twenty-seventh Great Britain annual report and accounts 31 March 1971-1972 ISBN 0 900085 71 1 Published by the Arts Council of Great Britai n 105 Piccadilly, London wtv oA u Designed and printed at Shenval Press Text set in `Monotype' Times New Roman 327 and 33 4 Cover: Wiggins Teape Centurion Text paper : Mellotex Smooth Superwhite cartridge 118g/m' Membership of the Council, Committees and Panels Council Photography Committee Patrick Gibson (Chairman) Serpentine Gallery Committee Sir John Witt (Vice-Chairman) The following co-opted members serve on one o r The Marchioness of Anglesey more of these committees : Richard Attenborough, CBE Professor Aaron Scharf The Lord Balfour of Burleigh Bil Gaskin s Lady Casso n George J. Hughes Colonel Sir William Crawshay, DSO, TD David Hurn Dr Cedric Thorpe Davie, OB E Paul Huxley Professor T. A. Dunn The Viscount Esher, CBE Drama Panel Lady Antonia Fraser J. W. Lambert, CBE, Dsc (Chairman) ) Sir William Glock, CB E Professor Roy Shaw (Deputy Chairman Peter Hall, CB E Miss Susanna Capon Stuart Hampshire Peter Cheeseman J. W. Lambert, CBE, Dsc Professor Philip Collins Professor Denis Matthews Miss Harriet Cruickshank s Sir John Pope-Hennessy, CBE Miss Constance Cumming The Hon Sir Leslie Scarman, OBE Peter Dews Professor Roy Sha w Patrick Donnell, DSO MBE The Lord Snow, CBE Miss Jane Edgeworth, Richard Findlater Art Panel Bernard Goss Sir John Pope-Hennessy, CBE (Chairman) Nickolas Grace Alan Bowness Mrs Jennifer Harri s Simon Chapman Philip Hedley Michael Compto n Peter Jame s Richard Cork Hugh Jenkins, MP Professor Christopher Cornford Oscar Lewenstei n Theo Crosby Dr A. -

30 September 2015 17 Queensberry Place, South Kensington, London SW7 2DT Tel: 020 7871 3515 Web: CALENDAR

24 — 30 September 2015 17 Queensberry Place, South Kensington, London SW7 2DT Tel: 020 7871 3515 Web: www.institut-francais.org.uk CALENDAR page thu 24 sep 6.15pm MAGICAL GIRL H dir. Carlos Vermut 4 309 Regent Street, London W1B 2UW Preceded by an introduction (tbc) Tel: 020 7911 5050 Web: www.regentstreetcinema.com 8.50pm MARSELLA H dir. Belén Macías 7 Introduced by director Belén Macías page fri 25 sep 8.40pm REQUISITOS PARA SER UNA PERSONA NORMAL H 7 fri 25 sep 6.30pm OCHO APELLIDOS VASCOS 8 dir. Leticia Dolera dir. Emilio Martínez Lázaro Preceded by an introduction by actor Manuel Burque sat 26 sep 6.30pm LAS OVEJAS NO PIERDEN EL TREN 4 sat 26 sep 4.30pm LA MUERTE EN LA ALCARRIA H dir. Fernando Pomares Piñol 7 dir. Álvaro Fernández Armero The film will be introduced by the director Preceded by the short CON BUENAS INTENCIONES 8.30pm ÄRTICO H dir. Gabriel Velázquez 4 and an introduction The film will be ollowedf by a Q&A with the director sun 27 sep 6.00pm TODO EL MUNDO LO SABE H 5 sun 27 sep 4.15pm A ESCONDIDAS H dir. Mikel Rueda 9 dir. Miguel Larraya Introduced by the director Introduced by the director tue 29 sep 6.30pm SNACKS: BOCADOS DE UNA REVOLUCIÓN 5 8.00pm LEARNING TO DRIVE 10 dir. Cristina Jolonch & Verónica Escuer dir. Isabel Coixet The screening will be followed by a round table The film will be preceded by an on-stage about this culinary revolution and the influence conversation between director Isabel Coixet and it has represented worldwide. -

Shakespeare on Film and Television in the Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division of the Library of Congress

SHAKESPEARE ON FILM AND TELEVISION IN THE MOTION PICTURE, BROADCASTING AND RECORDED SOUND DIVISION OF THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS Compiled by Zoran Sinobad January 2012 Introduction This is an annotated guide to moving image materials related to the life and works of William Shakespeare in the collections of the Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division of the Library of Congress. While the guide encompasses a wide variety of items spanning the history of film, TV and video, it does not attempt to list every reference to Shakespeare or every quote from his plays and sonnets which have over the years appeared in hundreds (if not thousands) of motion pictures and TV shows. For titles with only a marginal connection to the Bard or one of his works, the decision what to include and what to leave out was often difficult, even when based on their inclusion or omission from other reference works on the subject (see below). For example, listing every film about ill-fated lovers separated by feuding families or other outside forces, a narrative which can arguably always be traced back to Romeo and Juliet, would be a massive undertaking on its own and as such is outside of the present guide's scope and purpose. Consequently, if looking for a cinematic spin-off, derivative, plot borrowing or a simple citation, and not finding it in the guide, users are advised to contact the Moving Image Reference staff for additional information. How to Use this Guide Entries are grouped by titles of plays and listed chronologically within the group by release/broadcast date. -

Sir Ian Mclellan in Shakespeare

'ACTING GOOD PARTS WELL': SIR IAN McKELLEN IN SHAKESPEARE by HILARY EDITH W. LONG A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Arts of the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY The Shakespeare Institute School of English Faculty of Arts The University of Birmingham March 2000 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. SYNOPSIS This thesis examines the performances which have earned Sir lan McKellen a reputation as one of the foremost Shakespearean actors of the day. His reputation has been built on five major performances: Richard II, Macbeth, Coriolanus, lago and Richard III. His performances as Hamlet, Romeo, Leontes and Kent were only limited successes. This thesis places McKellen's performances in these roles in the specific context of the production as a whole. Where it is relevant it assesses the significance of the casting of other roles, the influence of the personality, style and interests of the director, the policy of the theatre company and the impact of the performance space. This thesis identifies patterns in McKellen's work determined by his own personality and sexuality, the Cambridge education he shares with Sir Peter Hall, John Barton and Trevor Nunn, and his relationships with other actors. -

T a K E Y O U R P L a C E 2 0

TAKE YOUR PLACE 2020 for performers and those who make performance possible 1 WE WANT WHAT YOU WANT This is to spend the rest of your working life doing what you are passionate about, can do well and make a living. So the motivation we had when our Institute started, and still have, matches yours. ach year we ACCOLADES survey our graduates, four Many of our graduates are award-winners. Here’s a selection from our 24-year history. Eyears after leaving us to find out if they are Academy Awards Music Week’s 30 Under 30 achieving this goal. The CO-PRODUCER OF BEST MOTION PICTURE 2013, 2014 & 2015 latest result, for the 82% OF THE YEAR NOMINEE (2019) of our 2014 graduates Artist & Manager Awards Musicians Benevolent Fund that we could find, MANAGER OF THE YEAR (2017) Songwriting Award WINNERS 2003, 2005, 2006, 2008 & 2011 showed 91% in work. Association of Lighting Designers You will find LIPA – Michael Northen Bursary National Encore Theatre Awards graduates performing WINNERS 2007, 2012, 2015, 2017 & 2018 THEATRE MANAGER OF THE YEAR (2012 & 2013) or making performance possible all over the BAFTAs Norwegian Grammys world. There are so DIALOGUE EDITOR BEST SHORT FILM WINNER (2017) BEST SOUND NOMINEE (2016) BEST POP GROUP ALBUM (2015) many we could tell you BEST NEWCOMER (2012) about, but we’ve had BRIT Awards BEST FEMALE ARTIST (2004) to limit ourselves to a CO-WRITERS OF BRITISH SINGLE WINNER (2017) few case studies in this BRITISH PRODUCER OF THE YEAR NOMINEE (2016) Off West End Awards CRITICS’ CHOICE NOMINEE (2016) prospectus on the course BEST SET DESIGNER WINNER (2017) pages. -

October 2018 Nickolas Grace Wayne Sleep OBE

President: Vice President: No. 504 - October 2018 Nickolas Grace Wayne Sleep OBE The Old Vic and the Nativity Play Liz Schafer reveals the part played by Lilian Baylis in the staging of the now traditional nativity play in England Christmas cards are now in the shops and, no doubt, nativity plays are being planned so it’s a good moment to acknowledge the part played by the Old Vic in the development of that great British institution, The Nativity Play. Because at the beginning of the twentieth century in Britain you had to go abroad to see a nativity play. And that is what Lilian Baylis did. In 1900, Baylis went on a holiday to Germany visiting the Rhine and Oberammergau with its famous Passion Play in its brand new theatre. Baylis was also a good friend of the now mostly forgotten but extraordinary controversialist, the Reverend Stewart Headlam, who founded the Church and Stage Guild in 1879. Headlam fought hard to improve attitudes towards theatre, and performers at a time when theatres were banned from staging biblical narratives, or even examining religious themes. In the UK at the time requests to the censor, the Lord Chamberlain, for permission to stage re-enactments of Biblical stories – whether made by theatre makers or vicars – were always refused, and even staging decorous tableaux accompanied by a gospel reading was a risky enterprise. Then in 1901 William Poel, who had worked at the Vic during 1881-83 under Emma Cons, staged the first modern stage production of the Mediaeval Christian morality play Everyman at the Charterhouse in London. -

Screens in Shakespeare: Hollywood Comes to Ephesus

Screens in Shakespeare: Hollywood comes to Ephesus. Trevor Nunn’s The Comedy of Errors (RSC, 1976) Anny Crunelle Vanrigh To cite this version: Anny Crunelle Vanrigh. Screens in Shakespeare: Hollywood comes to Ephesus. Trevor Nunn’s The Comedy of Errors (RSC, 1976). Shakespeare en devenir, Universite de Poitiers, 2020, Shakespeare, films et textes : théorie française et réception critique / Shakespeare, Screen and Texts: French Theory and Critical Reception, 15. hal-03154941 HAL Id: hal-03154941 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03154941 Submitted on 14 Apr 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Shakespeare en devenir ISSN électronique : 1958-9476 Courriel : [email protected] Screens in Shakespeare: Hollywood comes to Ephesus. Trevor Nunn’s e Comedy of Errors (RSC, 1976) Par Anny Crunelle Vanrigh Publication en ligne le 07 décembre 2020 Résumé Dans sa mise en scène demeurée légendaire de The Comedy of Errors (RSC 1976), Trevor Nunn convoque le cinéma hollywoodien du film muet aux classiques des années 50 (comédie musicale, film noir, screwball comedy) et aux blockbusters des années 70. L’intermodalité permet un réencodage de la grammaire d’origine de la pièce dans des codes qui fassent sens pour le spectateur d’aujourd’hui. -

Richard II Abraham Beame, Honorary Chairman/Paul Lepercq, Chairman/Donald M

(1'795-, oot3S-c 1 The Brooklyn Academy of Music 30 Lafayette Avenue, Brooklyn, N.Y. 11217 (212)6364100 Lichtenstein Executive Director BAM Harvey David Midland Director of Operations Sharon Rupert Director of Finance Leon Van Dyke Director of Development Charles Ziff Director of Promotion and Audience Development Jane Ward Production Manager Royal Bob Lussier Theatre Manager Daniel J. Sullivan Box Office Treasurer Betty Rosendorn Children's Program Administrator Shakespeare Sarah Walder Group Sales Representative William Mintzer Lighting Consultant to BAM Company Martha McGowan Benefit Coordinator John Springer Associates Benefit Publicity The St. Felix Street Corporation, a non-profit organization operating the Brooklyn Academy of Music Richard II Abraham Beame, Honorary Chairman/Paul Lepercq, Chairman/Donald M. Blinken, President/Richard C. Sachs, Treasurer/Harvey Lichtenstein, Secretary and Executive Director/Martin P. Carter/ Barbara lee Diamonstein/Donald Elliott/Mrs. Henry Epstein/Seth S. Faison/Richard M. Hexter/William Josephson/W. Barnabas McHenry/Mrs. Evelyn Ortner, ex-officio/Alan J. Patricof/David Picker/William Tobey/Edward L. Weisl, Jr., Administrator P.R.C.A. and Sebastian Leone, Brooklyn Borough President, members ex-officio. BRITISH THEATRE SEASON EVENTS (All performances Tuesday through Sunday) The Royal Shakespeare Company Richard II (eves.) Jan. 9-27; (mats.) Jan. 12, 13, 17, 20, 24, 27 Sylvia Plath (eves.) Jan. 15-27; (mats.) Jan. 20, 27 Hollow Crown (eves.) Apr. 18-20,27, 28; (mats.) Apr. 19, 28 Pleasure & Repentance (eves.) Apr. 21, 25, 26; (mats.) Apr. 21, 25 The Actors Company Wood Demon (eves.) Jan. 29, Feb. 7-12, 16, 17; (mats.) Feb. 10, 17 Knots (eves.) Jan. -

26 February 2016 Page 1 of 17

Radio 4 Listings for 20 – 26 February 2016 Page 1 of 17 SATURDAY 20 FEBRUARY 2016 Clare Balding joins Jenni Williams and her disabled three year SAT 11:00 The Week in Westminster (b072jwy1) old daughter, Eve, as they take their daily walk in the Surrey EU Special SAT 00:00 Midnight News (b0707w9t) Hills. These walks are the highlight of their day as both enjoy The latest national and international news from BBC Radio 4. being outside, admiring the views and watching the antics of Steve Richards and guests debate the implications of David Followed by Weather. their young and exuberant, golden retriever, Scout. Jenni talks Cameron's EU negotiation. candidly to Clare about how she and her husband, Steve have Producer: Peter Mulligan. come to terms with Eve's condition and how they feel blessed to SAT 00:30 Book of the Week (b070hsck) have such a happy and life affirming child. Benjamin Franklin in London Producer Lucy Lunt. SAT 11:30 From Our Own Correspondent (b0707wbb) A Man Dies Twice Episode 5 SAT 06:30 Farming Today (b0713f1d) Meeting the people populating the world of news. In this In the middle of the 18th century, Benjamin Franklin spent Farming Today This Week: Mental Health edition: thousands were massacred in the Bosnian town of almost two decades in London - at exactly the same time as Visegrad during the war there in 1992 - today, as Fergal Keane Mozart, Casanova and Handel. This is an enthralling biography One in four people in the UK are affected by serious mental ill- has been finding out, the authorities there want it to become a - not only of the man, but of the city when it was a hub of health, and it seems farmers are particularly at risk.