Lessons from Hollywood Cybercrimes: Combating Online Predators

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Syndication's Sitcoms: Engaging Young Adults

Syndication’s Sitcoms: Engaging Young Adults An E-Score Analysis of Awareness and Affinity Among Adults 18-34 March 2007 BEHAVIORAL EMOTIONAL “Engagement happens inside the consumer” Joseph Plummer, Ph.D. Chief Research Officer The ARF Young Adults Have An Emotional Bond With The Stars Of Syndication’s Sitcoms • Personalities connect with their audience • Sitcoms evoke a wide range of emotions • Positive emotions make for positive associations 3 SNTA Partnered With E-Score To Measure Viewers’ Emotional Bonds • 3,000+ celebrity database • 1,100 respondents per celebrity • 46 personality attributes • Conducted weekly • Fielded in 2006 and 2007 • Key engagement attributes • Awareness • Affinity • This Report: A18-34 segment, stars of syndicated sitcoms 4 Syndication’s Off-Network Stars: Beloved Household Names Awareness Personality Index Jennifer A niston 390 Courtney Cox-Arquette 344 Sarah Jessica Parker 339 Lisa Kudrow 311 Ashton Kutcher 297 Debra Messing 294 Bernie Mac 287 Matt LeBlanc 266 Ray Romano 262 Damon Wayans 260 Matthew Perry 255 Dav id Schwimme r 239 Ke ls ey Gr amme r 229 Jim Belushi 223 Wilmer Valderrama 205 Kim Cattrall 197 Megan Mullally 183 Doris Roberts 178 Brad Garrett 175 Peter Boyle 174 Zach Braff 161 Source: E-Poll Market Research E-Score Analysis, 2006, 2007. Eric McCormack 160 Index of Average Female/Male Performer: Awareness, A18-34 Courtney Thorne-Smith 157 Mila Kunis 156 5 Patricia Heaton 153 Measures of Viewer Affinity • Identify with • Trustworthy • Stylish 6 Young Adult Viewers: Identify With Syndication’s Sitcom Stars Ident ify Personality Index Zach Braff 242 Danny Masterson 227 Topher Grace 205 Debra Messing 184 Bernie Mac 174 Matthew Perry 169 Courtney Cox-Arquette 163 Jane Kaczmarek 163 Jim Belushi 161 Peter Boyle 158 Matt LeBlanc 156 Tisha Campbell-Martin 150 Megan Mullally 149 Jennifer Aniston 145 Brad Garrett 140 Ray Romano 137 Laura Prepon 136 Patricia Heaton 131 Source: E-Poll Market Research E-Score Analysis, 2006, 2007. -

Friday August 3

Movies starting Friday August 3 www.marcomovies.com America’s Original First Run Food Theater! We recommend that you arrive 30 minutes before ShowTime. “Christopher Robin” Rated PG Run Time 1:45 Starring Ewan McGregor and Haley Atwell Start 2:50 5:50 8:45 End 4:35 7:35 10:30 Rated PG for some action. “The Spy Who Dumped Me” Rated R Run Time 2:00 Starring Mila Kunis and Kate McKinnon Start 2:50 5:50 9:00 End 4:50 7:50 11:00 Rated R for violence, language throughout, some crude sexual material and graphic nudity. “Mission: Impossible - Fallout” Rated PG-13 Run Time 2:30 Starring Tom Cruise, Simon Pegg and Alex Baldwin Start 2:30 5:30 8:45 End 5:00 8:00 11:15 Rated PG-13 for violence and intense sequences of action, and for brief strong language. “Mamma Mia! Here We Go Again” Rated PG-13 Run Time 1:55 Starring Meryl Streep, Lily James and Amanda Seyfried Start 2:40 5:40 9:00 End 4:50 7:50 10:55 Rated PG-13 for some suggestive material. ***Prices*** Adults $13.00 (3D $16.50) Matinees, Seniors and Children under 12 $10.50 (3D $13.50) Visit Marco Movies at www.marcomovies.com facebook.com/MarcoMovies Christopher Robin (PG) • Ewan McGregor • Haley Atwell • In the heartwarming live action adventure "Disney's Christopher Robin," the young boy who loved embarking on adventures in the Hundred Acre Wood with a band of spirited and lovable stuffed animals, has grown up and lost his way. -

May 2014 Passages VOLUME XLIX Northwest Catholic, 29 Wampanoag Drive, West Hartford, Connecticut, 06117

Northwest May 2014 Passages VOLUME XLIX Northwest Catholic, 29 Wampanoag Drive, West Hartford, Connecticut, 06117 “Looking In Theater” Inspires Senior Class By Annie Berning ‘14 students from the was only for the senior class, responded if they were the impressed by the greater Hartford area. The the topics that the actors ones involved. performance. For Mrs. This year, the Northwest group is directed by Jonathan dealt with were realistic for Mrs. Williamson Williamson, who had worked Catholic school board Gillman of the Greater a college environment. The coordinated the performance. very hard to coordinate the initiated a new seminar Hartford Academy of the group performed eight short Last year, she attended a event, it was a great success. series titled “Life Skills,” Arts, a member of the Capital skits. Each one dealt with Looking In performance “The presentation by Looking with the goal of preparing Region Education Council racism, relationship issues, specifically for Catholic in Theatre surpassed my the members of the depression and suicide, school administrators. She expectations in two ways,” senior class for life roommate conflicts, or peer was very impressed with she recalled. “The actors post-graduation. The pressure at parties. The set what she saw and it became and the director, Jonathan school board has was simple and there were her dream to have Looking Gillman, involved in the already sponsored two no costumes, only dialogue In perform for the students of show were at such a high presentations this year, between the actors. The skits Northwest Catholic. Looking level. I was also impressed including one titled were largely open ended, In came last year as well to by the engagement of seniors “Personal Finance” and designed to inspire thoughts and their comments.” The a second titled “Your Kimberly Sanders about the issues at hand, students were also inspired Personal Brand.” Actors answer questions from the audi- rather than force a suggested to begin thinking about the These dealt with the ence while still in character. -

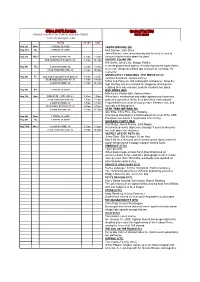

Cinema Augusta Program Coming Attractions Phone 86489999 to Check Session Times Visit Our Web Page

CINEMA AUGUSTA PROGRAM COMING ATTRACTIONS PHONE 86489999 TO CHECK SESSION TIMES VISIT OUR WEB PAGE www.cinemaaugusta.com MOVIE START END . Aug 1st Mon CINEMA CLOSED JASON BOURNE (M) Aug 2nd Tue CINEMA CLOSED Matt Damon, Julia Stiles. Jason Bourne, now remembering who he truly is, tries to Aug 3rd Wed JASON BOURNE (M) 6.30pm 8.20pm uncover hidden truths about his past. THE LEGEND OF TARZAN (M) 8.30pm 10.40pm SUICIDE SQUAD (M) Will Smith, Jared Leto, Margot Robbie. Aug 4th Thu JASON BOURNE (M) 6.20pm 8.30pm A secret government agency recruits imprisoned supervillains STAR TREK BEYOND (M) 8.40pm 10.50pm to execute dangerous black ops missions in exchange for clemency. ABSOLUTELY FABULOUS :THE MOVIE (CTC) Aug 5th Fri ICE AGE COLLISION COURSE (G) 4.45pm 6.20pm Jennifer Saunders, Joanna Lumley. STAR TREK BEYOND (M) 3D 6.30pm 8.40pm Edina and Patsy are still oozing glitz and glamor, living the JASON BOURNE (M) 8.50pm 10.55pm high life they are accustomed to; shopping, drinking and clubbing their way around London's trendiest hot-spots. Aug 6th Sat CINEMA CLOSED BAD MOMS (MA) Mila Kunis, Kristen Bell, Kathryn Hahn. Aug 7th Sun KIDS FLIX …ICE AGE (G) 9.30am 1.00pm When three overworked and under-appreciated moms are STAR TREK BEYOND (M) 1.10pm 3.20pm pushed beyond their limits, they ditch their conventional JASON BOURNE (M) 3.30pm 5.40pm responsibilities for a jolt of long overdue freedom, fun, and STAR TREK BEYOND (M) 3D 6.00pm 8.10pm comedic self-indulgence. -

Television Academy Awards

2019 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Comedy Series A.P. Bio Abby's After Life American Housewife American Vandal Arrested Development Atypical Ballers Barry Better Things The Big Bang Theory The Bisexual Black Monday black-ish Bless This Mess Boomerang Broad City Brockmire Brooklyn Nine-Nine Camping Casual Catastrophe Champaign ILL Cobra Kai The Conners The Cool Kids Corporate Crashing Crazy Ex-Girlfriend Dead To Me Detroiters Easy Fam Fleabag Forever Fresh Off The Boat Friends From College Future Man Get Shorty GLOW The Goldbergs The Good Place Grace And Frankie grown-ish The Guest Book Happy! High Maintenance Huge In France I’m Sorry Insatiable Insecure It's Always Sunny in Philadelphia Jane The Virgin Kidding The Kids Are Alright The Kominsky Method Last Man Standing The Last O.G. Life In Pieces Loudermilk Lunatics Man With A Plan The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel Modern Family Mom Mr Inbetween Murphy Brown The Neighborhood No Activity Now Apocalypse On My Block One Day At A Time The Other Two PEN15 Queen America Ramy The Ranch Rel Russian Doll Sally4Ever Santa Clarita Diet Schitt's Creek Schooled Shameless She's Gotta Have It Shrill Sideswiped Single Parents SMILF Speechless Splitting Up Together Stan Against Evil Superstore Tacoma FD The Tick Trial & Error Turn Up Charlie Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt Veep Vida Wayne Weird City What We Do in the Shadows Will & Grace You Me Her You're the Worst Young Sheldon Younger End of Category Outstanding Drama Series The Affair All American American Gods American Horror Story: Apocalypse American Soul Arrow Berlin Station Better Call Saul Billions Black Lightning Black Summer The Blacklist Blindspot Blue Bloods Bodyguard The Bold Type Bosch Bull Chambers Charmed The Chi Chicago Fire Chicago Med Chicago P.D. -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 90Th Academy Awards Alien

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 90TH ACADEMY AWARDS ALIEN: COVENANT Actors: Michael Fassbender. Billy Crudup. Danny McBride. Demian Bichir. Jussie Smollett. Nathaniel Dean. Alexander England. Benjamin Rigby. Uli Latukefu. Goran D. Kleut. Actresses: Katherine Waterston. Carmen Ejogo. Callie Hernandez. Amy Seimetz. Tess Haubrich. Lorelei King. ALL I SEE IS YOU Actors: Jason Clarke. Wes Chatham. Danny Huston. Actresses: Blake Lively. Ahna O'Reilly. Yvonne Strahovski. ALL THE MONEY IN THE WORLD Actors: Christopher Plummer. Mark Wahlberg. Romain Duris. Timothy Hutton. Charlie Plummer. Charlie Shotwell. Andrew Buchan. Marco Leonardi. Giuseppe Bonifati. Nicolas Vaporidis. Actresses: Michelle Williams. ALL THESE SLEEPLESS NIGHTS AMERICAN ASSASSIN Actors: Dylan O'Brien. Michael Keaton. David Suchet. Navid Negahban. Scott Adkins. Taylor Kitsch. Actresses: Sanaa Lathan. Shiva Negar. AMERICAN MADE Actors: Tom Cruise. Domhnall Gleeson. Actresses: Sarah Wright. AND THE WINNER ISN'T ANNABELLE: CREATION Actors: Anthony LaPaglia. Brad Greenquist. Mark Bramhall. Joseph Bishara. Adam Bartley. Brian Howe. Ward Horton. Fred Tatasciore. Actresses: Stephanie Sigman. Talitha Bateman. Lulu Wilson. Miranda Otto. Grace Fulton. Philippa Coulthard. Samara Lee. Tayler Buck. Lou Lou Safran. Alicia Vela-Bailey. ARCHITECTS OF DENIAL ATOMIC BLONDE Actors: James McAvoy. John Goodman. Til Schweiger. Eddie Marsan. Toby Jones. Actresses: Charlize Theron. Sofia Boutella. 90th Academy Awards Page 1 of 34 AZIMUTH Actors: Sammy Sheik. Yiftach Klein. Actresses: Naama Preis. Samar Qupty. BPM (BEATS PER MINUTE) Actors: 1DKXHO 3«UH] %LVFD\DUW $UQDXG 9DORLV $QWRLQH 5HLQDUW] )«OL[ 0DULWDXG 0«GKL 7RXU« Actresses: $GªOH +DHQHO THE B-SIDE: ELSA DORFMAN'S PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHY BABY DRIVER Actors: Ansel Elgort. Kevin Spacey. Jon Bernthal. Jon Hamm. Jamie Foxx. -

The Lounge Offers Study Space BHS Cheerleaders and ASB Plan

October 20, 2017 Volume 49/Issue 3 Burroughs High School, Ridgecrest, CA 93555 BHS Cheerleaders and ASB plan spirited HOCO week by Kylie Griffith Powderpuff and especially building cheerleader. tions are important, improvements our cheerleaders believe that the Although for most Burroughs our Homecoming floats. I would Homecoming traditions are year to year are necessary to keep school spirit and excitement make students Homecoming week is pure say we spend about 30-plus hours always part of this exciting week. those traditions. it all worth it. fun and games, for our cheerleaders planning the activities for Home- “There are so many traditions Enyssa Armendariz stated, “This “It’s fun to see people joining and ASB it is a time for hard work coming,” Saralynn estimated. that go on for Homecoming, includ- year, we are changing the decora- in and cheering with you,” said and preparation. Unlike other danc- What’s the biggest demand on ing decorating the whole campus tions for the school by eliminating Schnuderl. es throughout the year, Homecom- their time? “Floatbuilding, defi- and field, garage door posters for the use of balloons because they “Homecoming is what everyone ing is run by the cheerleaders, not nitely,” said ASB Historian Malia our senior boys, and recognizing have caused a big mess in previ- looks forward to and the cheerlead- ASB. These girls work very hard Camacho. This year’s float theme all of the football players!” said ous years.” ers love to help prepare for it!” to make sure that Homecoming is is California landmarks. The fresh- Varsity Cheerleader Taylor Dugan. -

Film Schedule Summary Governors Crossing 14 1402 Hurley Drive Report Dates: Friday, August 17, 2018 - Thursday, August 23, 2018 Sevierville, TN 37862, (865) 366-1752

Film Schedule Summary Governors Crossing 14 1402 Hurley Drive Report Dates: Friday, August 17, 2018 - Thursday, August 23, 2018 Sevierville, TN 37862, (865) 366-1752 **************************************************************STARTING FRIDAY, AUG 17*************************************************************** ALPHA PG13 1 Hours 36 Minutes FRIDAY - THURSDAY 12:45 pm 02:55 pm 05:05 pm 07:15 pm 09:25 pm Kodi Smit-McPhee, Priya Rajaratnam, Leonor Varela, Jens Hultn, Natassia Malthe, Jhannes Haukur Jhannesson --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- *MILE 22 SXS R 1 Hours 36 Minutes FRIDAY - THURSDAY 12:20 pm 02:35 pm 04:50 pm 07:05 pm 09:20 pm Mark Wahlberg, Lauren Cohan, Ronda Rousey --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ************************************************************************CONTINUING************************************************************************ CRAZY RICH ASIANS PG13 2 Hours 1 Minutes FRIDAY - THURSDAY 01:00 pm 04:00 pm 07:00 pm 09:40 pm Constance Wu, Michelle Yeoh, Henry Golding --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- *THE MEG SXS PG13 1 Hours 53 Minutes FRIDAY - THURSDAY 11:50 am 02:20 pm 04:50 pm 07:20 pm 09:50 pm Ruby Rose, Jason Statham, Rainn Wilson -

Raritan Review

RARITANRARITAN HIGHREVIEW SCHOOL’S OFFICIAL NEWSPAPER Valentine’s Day Edition STUPID CUPID nus cannot find her. Here, Psyche finds herself approaching a beautiful mansion where she BY: KIERA MALLEY decides to make herself at home. In her time With Valentine’s day approaching, cou- spent at this mansion, she is waited on by invis- ples everywhere are beginning to plan romantic ible servants and eventually falls in love with evenings for one another. It has been said that a man in the dark. Having never seen her new Cupid, the Roman God of desire, flies around love, she is eventually encouraged by her sisters the world on this night shooting his arrows of to go look upon him in the night. While doing love at deserving couples, locking their fate so, she accidentally wakes up her love, who she together. While Cupid works his magic, the discovered to be Cupid himself, angering him amount of love in the atmosphere leaves people and causing him to flee. On a quest to find her swooning over one another. The myth of cupid love, Psyche goes to Venus herself for help. Still has been around for thousands of years, resur- angry, Venus sends Psyche on several daunting facing each February with the takeover of this FEB. 2016 tasks before offering her help. In the mean- Hallmark holiday. But how did Cupid come to time, Cupid found out about his mother’s de- claim the throne of Valentine’s Day? mands, then asking the God Jupiter to order her The son of Venus and Mars, Cupid is typi- to stop. -

NOMINEES for the 68Th ANNUAL GOLDEN GLOBE AWARDS

NOMINEES FOR THE 68th ANNUAL GOLDEN GLOBE AWARDS Best Motion Picture - Drama Best Screenplay - Motion Picture Best Performance by an Actress in Black Swan (2010) 127 Hours (2010): Danny Boyle, Simon Beaufoy a Mini-Series or a Motion Picture The Fighter (2010) Inception (2010): Christopher Nolan Made for Television Inception (2010) The Kids Are All Right (2010): Stuart Blumberg, Hayley Atwell for The Pillars of the Earth (2010) The King’s Speech (2010) Lisa Cholodenko Claire Danes for Temple Grandin (2010) The Social Network (2010) The King’s Speech (2010): David Seidler Judi Dench for Cranford (2007) The Social Network (2010): Aaron Sorkin Romola Garai for Emma (2009) Best Motion Picture - Jennifer Love Hewitt for The Client List (2010) Musical or Comedy Best Original Song - Motion Picture Alice in Wonderland (2010) Best Performance by an Actor Burlesque (2010/I) Burlesque (2010/I): Samuel Dixon, Christina Aguilera, in a Television Series - The Kids Are All Right (2010) Sia Furler(“Bound to You”) Musical or Comedy Burlesque (2010/I): Diane Warren(“You Haven’t Seen Red (2010/I) Alec Baldwin for 30 Rock (2006) The Last of Me”) The Tourist (2010) Steve Carell for The Office (2005) Country Strong (2010): Bob DiPiero, Tom Douglas, Hillary Lindsey, Troy Verges(“Coming Home”) Thomas Jane for Hung (2009) Best Performance by an Actor Matthew Morrison for Glee (2009) in a Motion Picture - Drama The Chronicles of Narnia: The Voyage of the Dawn Treader (2010): Carrie Underwood, David Hodges, Jim Parsons for The Big Bang Theory (2007) Jesse Eisenberg for The Social Network (2010) Hillary Lindsey(“There’s A Place For Us”) Best Performance by an Actress Colin Firth for The King’s Speech (2010) Tangled (2010): Alan Menken, Glenn Slater James Franco for 127 Hours (2010) (“I See the Light”) in a Television Series - Ryan Gosling for Blue Valentine (2010) Musical or Comedy Mark Wahlberg for The Fighter (2010) Best Original Score - Toni Collette for United States of Tara (2009) Motion Picture Edie Falco for Nurse Jackie (2009) Best Performance by an Actress 127 Hours (2010): A.R. -

Movie Data Analysis.Pdf

FinalProject 25/08/2018, 930 PM COGS108 Final Project Group Members: Yanyi Wang Ziwen Zeng Lingfei Lu Yuhan Wang Yuqing Deng Introduction and Background Movie revenue is one of the most important measure of good and bad movies. Revenue is also the most important and intuitionistic feedback to producers, directors and actors. Therefore it is worth for us to put effort on analyzing what factors correlate to revenue, so that producers, directors and actors know how to get higher revenue on next movie by focusing on most correlated factors. Our project focuses on anaylzing all kinds of factors that correlated to revenue, for example, genres, elements in the movie, popularity, release month, runtime, vote average, vote count on website and cast etc. After analysis, we can clearly know what are the crucial factors to a movie's revenue and our analysis can be used as a guide for people shooting movies who want to earn higher renveue for their next movie. They can focus on those most correlated factors, for example, shooting specific genre and hire some actors who have higher average revenue. Reasrch Question: Various factors blend together to create a high revenue for movie, but what are the most important aspect contribute to higher revenue? What aspects should people put more effort on and what factors should people focus on when they try to higher the revenue of a movie? http://localhost:8888/nbconvert/html/Desktop/MyProjects/Pr_085/FinalProject.ipynb?download=false Page 1 of 62 FinalProject 25/08/2018, 930 PM Hypothesis: We predict that the following factors contribute the most to movie revenue. -

FWB Production Notes

PRODUCTION NOTES "We need to talk." "We're heading in different directions." "You deserve better than me." "Let's stay friends." Dylan (JUSTIN TIMBERLAKE) and Jamie (MILA KUNIS) certainly aren't in a settling-down frame of mind. When New York-based executive recruiter Jamie trains her considerable headhunting skills on luring hotshot LA-based art director Dylan to take a dream job in the Big Apple, they quickly realize what kindred spirits they are. They've each been through so many failed relationships that they're both ready to give up on love and focus on having fun. So when Dylan relocates to New York and the pair start hanging out regularly, they share plenty of laughs over a twin belief that love is a myth propagated by Hollywood movies. That's when these two begin a deliciously sexy, decidedly grown-up experiment. Could these two fast friends – who are successful, unattached, and scornful of commitment - explore new terrain? If they add casual "no emotions" sex to their friendship, can they avoid all the pitfalls that come with thinking about someone else as more than just a pal? As two people weaned on the disappointing promises of romantic comedies, Dylan and Jamie shouldn’t be entirely surprised when their bold move becomes a bawdy, sexy ride into uncharted territory, exposing much more of themselves than they ever thought they'd get to see. Friends with Benefits stars Justin Timberlake (The Social Network), Mila Kunis (Black Swan), Patricia Clarkson (Easy A), Jenna Elfman (“Dharma & Greg”), Bryan 1 Greenberg (“How to Make It in America”), with Richard Jenkins (Dear John) and Woody Harrelson (2012).