UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Types of Dance Styles

Types of Dance Styles International Standard Ballroom Dances Ballroom Dance: Ballroom dancing is one of the most entertaining and elite styles of dancing. In the earlier days, ballroom dancewas only for the privileged class of people, the socialites if you must. This style of dancing with a partner, originated in Germany, but is now a popular act followed in varied dance styles. Today, the popularity of ballroom dance is evident, given the innumerable shows and competitions worldwide that revere dance, in all its form. This dance includes many other styles sub-categorized under this. There are many dance techniques that have been developed especially in America. The International Standard recognizes around 10 styles that belong to the category of ballroom dancing, whereas the American style has few forms that are different from those included under the International Standard. Tango: It definitely does take two to tango and this dance also belongs to the American Style category. Like all ballroom dancers, the male has to lead the female partner. The choreography of this dance is what sets it apart from other styles, varying between the International Standard, and that which is American. Waltz: The waltz is danced to melodic, slow music and is an equally beautiful dance form. The waltz is a graceful form of dance, that requires fluidity and delicate movement. When danced by the International Standard norms, this dance is performed more closely towards each other as compared to the American Style. Foxtrot: Foxtrot, as a dance style, gives a dancer flexibility to combine slow and fast dance steps together. -

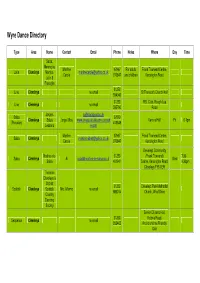

Wyre Dance Directory

Wyre Dance Directory Type Area Name Contact Email Phone Notes Where Day Time Salsa, Merengue, Martine 07967 For adults Frank Townend Centre, Latin Cleveleys Mambo, [email protected] Carole 970847 and children Kensington Road Latin & Freestyle 01253 Line Cleveleys no email St Theresa's Church Hall 594043 01253 RBL Club, Rough Lea Line Cleveleys no email 595790 Road Jorge’s [email protected] Salsa 07879 Cleveleys Salsa Jorge Ulloa www.jorgessalsalessons.yolasit Verona Hall Fri 6-7pm (Peruvian) 413649 Lessons e.com Martine 07967 Frank Townend Centre, Salsa Cleveleys [email protected] Carole 970847 Kensington Road Cleveleys Community Noches-de- 01253 (Frank Townend) 7.30- Salsa Cleveleys Al [email protected] Wed Salsa 401941 Centre, Kensington Road, 9.30pm Cleveleys FY5 1ER Thornton Cleveleys & District 01253 Cleveleys Park Methodist Scottish Cleveleys Scottish Mrs. Marmo no email 886014 Church, West Drive Country Dancing Society Senior Citizens Hall, 01253 Victoria Road, Sequence Cleveleys no email 852462 Anchorsholme Friendly Club Phil Kelsall 01253 Ballroom Fleetwood [email protected] Organists Marine Hall Chris Hopkins 771141 Christine 01253 Ballroom Fleetwood [email protected] Victoria Street Cheeseman 779746 07874 Farmer Parrs, Fleetwood Ballroom / Latin Fleetwood Alison Slinger [email protected] Improvers Fri 7-8pm 922223 Road 07874 Practise Farmer Parrs, Fleetwood Ballroom / Latin Fleetwood Alison Slinger [email protected] Fri 8-9.30 922223 session Road 07874 Social Farmer -

Masterclasses Are Maximum Capacity, Fixed Couple Workshops Designed for More Teacher/Pupil Interaction. There Is a Range Of

Masterclasses Blush 19 Masterclasses are maximum capacity, fixed couple workshops designed for more teacher/pupil interaction. There is a range of workshops available that can be booked at The Weather Centre (information desk in the main foyer) at a cost of £5 per head ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Saturday 10.45am – 11.45am: Flying Low: Baby Aerials with Tony & Hayley Epps (Partnered Masterclass) These two are aerials masters, and veterans at teaching people how to safely, accurately and stylishly perform impressive, showstopping lifts. Baby Aerials keep both of the ladies feet close to the ground and allow participants to explore being airborne, without the pressure of lifting the lady over the top of the head! Suitable for Intermediate + Dancers and above – Signed Disclaimer Required ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Saturday 12pm - 1pm: Collegiate Shag with Lyndsey Bennett (Partnered Masterclasses) Just in time for Swingers Hour, Lyndsey brings you a brand new style of Rock ‘n’ Roll for you and your partner to sample. Up tempo, energetic and undeniably the most fun you will have all weekend. You can learn the basic step, practise some creative and varied patterns, and then head downstairs to show off your new skills in the Boudoir bar during Tiggerbabe’s set! Suitable for Intermediate + Dancers and above ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Saturday 1.15pm – 2.15pm & Sunday 6.15pm – 7.15pm: Ladies Styling 1 & 2 with Becki Rendell (Solo Masterclass) With a background in Ceroc, Salsa, Line Dance, Merengue, Zumba & Bachata, Becki has many styles to add variation and the wow factor to her Ceroc dancing. As an experienced Ladies Styling instructor, you can expect this Masterclass to incorporate Top - Toe Basics & Posture, Ceroc Rock Back Step with Latin Style, Spare Arms and Combinations, Shoulders, Hips and Hand Movements. -

'What Ever Happened to Breakdancing?'

'What ever happened to breakdancing?' Transnational h-hoy/b-girl networks, underground video magazines and imagined affinities. Mary Fogarty Submitted in partial fulfillment Of the requirements for the degree of Interdisciplinary MA in Popular Culture Brock University St. Catharines, Ontario © November 2006 For my sister, Pauline 111 Acknowledgements The Canada Graduate Scholarship (SSHRC) enabled me to focus full-time on my studies. I would also like to express my deepest gratitude to my committee members: Andy Bennett, Hans A. Skott-Myhre, Nick Baxter-Moore and Will Straw. These scholars have shaped my ideas about this project in crucial ways. I am indebted to Michael Zryd and Francois Lukawecki for their unwavering kindness, encouragement and wisdom over many years. Steve Russell patiently began to teach me basic rules ofgrammar. Barry Grant and Eric Liu provided comments about earlier chapter drafts. Simon Frith, Raquel Rivera, Anthony Kwame Harrison, Kwande Kefentse and John Hunting offered influential suggestions and encouragement in correspondence. Mike Ripmeester, Sarah Matheson, Jeannette Sloniowski, Scott Henderson, Jim Leach, Christie Milliken, David Butz and Dale Bradley also contributed helpful insights in either lectures or conversations. AJ Fashbaugh supplied the soul food and music that kept my body and mind nourished last year. If AJ brought the knowledge then Matt Masters brought the truth. (What a powerful triangle, indeed!) I was exceptionally fortunate to have such noteworthy fellow graduate students. Cole Lewis (my summer writing partner who kept me accountable), Zorianna Zurba, Jana Tomcko, Nylda Gallardo-Lopez, Seth Mulvey and Pauline Fogarty each lent an ear on numerous much needed occasions as I worked through my ideas out loud. -

WIN “Thirty-Seven-2-Eleven” WIN “Thirty-Se Bobby Dsawyer • • • • DANCES INCLUDING: CARELESS WHISPER · MO · WHISPER CARELESS INCLUDING: DANCES

The monthlymonthly magazine dedicatededicatedd to Line dancing Issue: 117 • February 2006 • £3 • Westlife • Tampa Bay Line Dance Classic • A Judge’s View • A day in the life of Glenn Rogers Bobby D Sawyer 02 771366 650031 WIN “Thirty-Se“Thirty-Seven-2-Eleven”ven-2-Eleven” 9 13 DANCES INCLUDING: CARELESS WHISPER · MOMMA MIA · 4 WHEELS TURNING · EASY TOUCH LD Cover Jan 06 1 6/1/06, 5:47:26 pm Line Dance Weekends from HOLIDAYS 20062006 £69.00 EASTER SPRING BANK HOLIDAY Morecambe Singles Special £69 Carlisle Easter Canter from £145 3 Days/ 2 nights Broadway Hotel, East Promenade 4 Days /3 nights Crown and Mitre Hotel, Carlisle Carlisle Spring Bank Holiday Dancing: each evening with a workshop on Saturday morning and Canter from £99 Lots of single rooms on this holiday- no supplement instruction on Sunday morning. You leave after breakfast on Monday. 3 Days /2 nights Crown and Mitre Hotel, Carlisle Solo Artist – Billy Bubba King (Saturday) Artists- Old Guns(Saturday) Dave Sheriff (Sunday) Dancing: each evening with a workshop on Sunday morning and Dance Instruction/Disco: Lizzie Clarke instruction on Monday morning. You leave after noon on Monday. Dance Instruction and Disco: Steve Mason Starts: Friday 27 Jan Finishes: Sunday 29 Jan 2006 Starts: Friday 14 April Finishes: Monday 17 April 2006 Artists- Blue Rodeo(Saturday) Diamond Jack (Sunday) Coaches available from Tyneside, Teesside, East Midlands, Dance Instruction and Disco: Steve Mason SELF DRIVE – £69 South and West Yorkshire Starts: Saturday 27 May Finishes: Monday 29 May 2006 SELF DRIVE – £145 BY COACH - £175 Coach available from East and North Yorkshire, Teesside and Tyneside Cumbrian Carnival £109 SELF DRIVE – £99 BY COACH - £129 3 Days /2 nights Cumbria Grand Hotel, Grange- Morecambe Easter Magic from £119 over-Sands 4 Days /3 nights Headway Hotel, East Promenade Artists- Jim Clark (Friday) Paul Bailey (Saturday) Dancing: each evening with a workshop on Saturday morning and St Annes Spring Bank Holiday Dance Instruction/Disco: Doreen Egan instruction on Sunday morning. -

NEW ORLEANS 2Nd LINE

PVDFest 2018 presents Jazz at Lincoln Center NEW ORLEANS 2nd LINE Workshop preparation info for teachers. Join the parade! Saturday, June 9, 3:00 - 4:00 pm, 170 Washington Street stage. 4:00 - 5:00 pm, PVDFest parade winds through Downtown, ending at Providence City Hall! PVDFest 2018: a FirstWorks Arts Learning project Table of Contents with Jazz at Lincoln Center A key component of FirstWorks, is its dedication to providing transformative arts experiences to underserved youth across Rhode Island. The 2017-18 season marks the organization’s fifth year of partnership with Jazz at Lincoln Center. FirstWorks is the only organization in Southern New England participating in this highly innovative program, which has become a cornerstone of our already robust Arts Learning program by incorporating jazz as a teaching method for curricular materials. Table of Contents . 2 New Orleans History: Social Aid Clubs & 2nd Lines . 3 Meet Jazz at Lincoln Center . .. 6 Who’s Who in the Band? . 7 Sheet Music . 8 Local Version: Meet Pronk! . 12 Teacher Survey . .. 14 Student Survey. .15 Word Search . .16 A young parade participant hoists a decorative hand fan and dances as the parade nears the end of the route on St. Claude Avenue in New Orleans. Photo courtesy of Tyrone Turner. PVDFest 2018: a FirstWorks Arts Learning project 3 with Jazz at Lincoln Center NOLA History: Social Aid Clubs and 2nd Lines Discover the history of New Orleans second line parades and social aid clubs, an important part of New Orleans history, past and present. By Edward Branley @nolahistoryguy December 16, 2013 Say “parade” to most visitors to New Orleans, and their thoughts shift immediately to Mardi Gras. -

Garage House Music Whats up with That

Garage House Music whats up with that Future funk is a sample-based advancement of Nu-disco which formed out of the Vaporwave scene and genre in the early 2010s. It tends to be more energetic than vaporwave, including elements of French Home, Synth Funk, and making use of Vaporwave modifying techniques. A style coming from the mid- 2010s, often explained as a blend of UK garage and deep home with other elements and strategies from EDM, popularized in late 2014 into 2015, typically mixes deep/metallic/sax hooks with heavy drops somewhat like the ones discovered in future garage. One of the very first house categories with origins embeded in New York and New Jersey. It was named after the Paradise Garage bar in New york city that operated from 1977 to 1987 under the prominent resident DJ Larry Levan. Garage house established along with Chicago home and the outcome was home music sharing its resemblances, affecting each other. One contrast from Chicago house was that the vocals in garage house drew stronger impacts from gospel. Noteworthy examples consist of Adeva and Tony Humphries. Kristine W is an example of a musician involved with garage house outside the genre's origin of birth. Also understood as G-house, it includes very little 808 and 909 drum machine-driven tracks and often sexually explicit lyrics. See likewise: ghettotech, juke house, footwork. It integrates components of Chicago's ghetto house with electro, Detroit techno, Miami bass and UK garage. It includes four-on-the-floor rhythms and is normally faster than a lot of other dance music categories, at approximately 145 to 160 BPM. -

2018/19 Hip Hop Rules & Regulations

2018/19 Hip Hop Rules for the New Zealand Schools Hip Hop Competition Presented by the New Zealand Competitive Aerobics Federation 2018/19 Hip Hop Rules, for the New Zealand Schools Hip Hop Championships © New Zealand Competitive Aerobic Federation Page 1 PART 1 – CATEGORIES ........................................................................................................................................................ 3 1.1 NSHHC Categories .............................................................................................................................................. 3 1.2 Hip Hop Unite Categories .................................................................................................................................. 3 1.3 NSHHC Section, Division, Year Group, & Grade Overview ................................................................................ 3 1.3.1 Adult Age Division ........................................................................................................................................ 3 1.3.2 Allowances to Age Divisions (Year Group) for NSHHC ................................................................................ 4 1.4 Participation Limit .............................................................................................................................................. 4 Part 2 – COMPETITION REQUIREMENTS ........................................................................................................................... 5 2.1 Performance Area ............................................................................................................................................. -

Rhythm, Dance, and Resistance in the New Orleans Second Line

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles “We Made It Through That Water”: Rhythm, Dance, and Resistance in the New Orleans Second Line A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnomusicology by Benjamin Grant Doleac 2018 © Copyright by Benjamin Grant Doleac 2018 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION “We Made It Through That Water”: Rhythm, Dance, and Resistance in the New Orleans Second Line by Benjamin Grant Doleac Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnomusicology University of California, Los Angeles, 2018 Professor Cheryl L. Keyes, Chair The black brass band parade known as the second line has been a staple of New Orleans culture for nearly 150 years. Through more than a century of social, political and demographic upheaval, the second line has persisted as an institution in the city’s black community, with its swinging march beats and emphasis on collective improvisation eventually giving rise to jazz, funk, and a multitude of other popular genres both locally and around the world. More than any other local custom, the second line served as a crucible in which the participatory, syncretic character of black music in New Orleans took shape. While the beat of the second line reverberates far beyond the city limits today, the neighborhoods that provide the parade’s sustenance face grave challenges to their existence. Ten years after Hurricane Katrina tore up the economic and cultural fabric of New Orleans, these largely poor communities are plagued on one side by underfunded schools and internecine violence, and on the other by the rising tide of post-disaster gentrification and the redlining-in- disguise of neoliberal urban policy. -

How Breakdancing Taught Me to Be a Technical Artist

How breakdancing taught me to be a technical artist Robbert-Jan Brems Technical Artist Codemasters Hello ladies and gentlemen, my name is Robbert-Jan Brems. I'm currently technical artist at Codemasters and here to present you my talk : “How breakdancing taught me to be a technical artist” I only have been working as a professional technical artist in the video game industry for just over a year, but I have been breakdancing for almost nine years, and dancing for almost seventeen. The reason I am telling you this will become more apparent later on. Just out of curiosity, are there any breakdancers in this room? Well, the good news is that you do not need any breakdance related experiences to understand this talk. The main reason why I wanted to do this talk was because I have the feeling that as a person it is really easy to be looking through the same window as everybody else. What I mean with that is when we follow the same route to find knowledge as everybody else, we end up knowing the same things while missing out on other potentially important knowledge. By telling you my life story as a breakdancer and a game developer I want to illustrate how I reflect the knowledge that I obtained through breakdancing to my profession as a technical artist. So, the goal of my talk is to hopefully inspire people to start looking for knowledge by looking at learning from a different perspective. Once upon a time ... I started dancing when I was around 7 years old. -

MUSIC, Dvds, PROGRAMS, PE CLASSES & SOUND SYSTEMS

MUSIC, DVDs, PROGRAMS, PE CLASSES & SOUND SYSTEMS ® and “Hi! I’m Christy Lane, creator of Dare to Dance owner of Christy Lane Enterprises. How can we help you? As you browse through this catalog, you will notice we expanded our line of products and services. When our company was established 20 years ago our philosophy was simple. To educate children that dance can benefit them physically, mentally, That's me on my first video shoot. socially, and emotionally. We did this by producing quality educational products for the physical Catalog Listings: education teachers and dance studio instructors. LINE DANCING Our customer base has expanded tremendously over PARTY DANCING the years and so has the popularity of dance. Now, DECADE DANCING moms, dads, single adults, seniors, and kids who HIP HOP have never danced before are dancing! So join the PARTNER/BALLROOM fun!” LATIN DANCING SQUARE DANCING AMERICA SPORTS & NOVELTY MULTICULTURAL FOLK Christy Lane is one of America’s most well-known and respected dance instructors. Her DANCING extensive dance training has led her to become an acknowledged dance educator, producer, choreographer, and writer. Her work has been recognized by U.S. News and World Report, AFRICAN-CARIBBEAN American Fitness, USA Today and Shape Magazine. Her credits include Disney, Pepsi and DANCING Capezio to name a few. A former private dance studio owner, she tours nationally and her PHYSICAL FITNESS conventions and workshops have delighted thousands of all ages. MUSIC EDITING JAZZ DANCING TAP DANCING DANCE CONVENTIONS HOLIDAY DANCE SHIRTS DANCE FLOORS SOUND SYSTEMS & MICROPHONES TEACHER WORKSHOPS “Christy Lane has the magic to motivate the non-dancer and insight to move DANCE SCHOOL ASSEMBLIES accomplished dancers to the next level.”-Bud Turner, P.E. -

Line Dance Terminology

· Forward right diagonal (wall) Line Dance · Forward left diagonal (center) · Reverse right diagonal (wall) Terminology · Reverse left diagonal (center) · Partner Alignment: The symmetric alignment of a couple. This list of line dance terms was collected AMALGAMATIONS from Country Dance Lines Magazine (CDL) a.k.a. Clusters, Combinations. A group or [defunct] and the National Teachers sequence of dance figures or patterns. Association (NTA) Glossary. Text may have AND been modified slightly for formatting Used when 2 movements are to be done purposes, but, in general, the terms and simultaneously. For example, definitions are exactly as provided by CDL 1. Step forward and clap hands. and NTA. A. Half of a quick count = "1&" or &1" B. A call, such as "ready and" Definitions from CDL look like this. & (AMPERSAND) Definitions from NTA look like this. The upbeat that precedes or follows the whole When both agreed on exactly the same downbeat. &1 precedes the beat, 1& follows the wording, the definition looks like this. beat. Unlike the previous usage of the term Definitions from elsewhere look like this. "and", the ampersand is used when "Step forward and clap hands" means two separate movements, and is notated in step descriptions A as: 1 Step forward on Left foot ACCENT & Clap Emphasis on a particular step or move in a AND STEP pattern, or, in music, the emphasis on a certain Signifies weight change with a movement. For beat in a measure. instance, in describing the first three steps in a Dance: Special emphasis to a movement Grapevine right, the description would read: Music: Special emphasis to a heavy beat in 1 Step to the right with Right foot.