First Assignment (PDF)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Race, Markets, and Hollywood's Perpetual Antitrust Dilemma

Michigan Journal of Race and Law Volume 18 2012 Race, Markets, and Hollywood's Perpetual Antitrust Dilemma Hosea H. Harvey Temple University, James E. Beasley School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjrl Part of the Antitrust and Trade Regulation Commons, Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Law and Race Commons Recommended Citation Hosea H. Harvey, Race, Markets, and Hollywood's Perpetual Antitrust Dilemma, 18 MICH. J. RACE & L. 1 (2012). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjrl/vol18/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Michigan Journal of Race and Law by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RACE, MARKETS, AND HOLLYWOOD'S PERPETUAL ANTITRUST DILEMMA Hosea H. Harvey* This Article focuses on the oft-neglected intersection of racially skewed outcomes and anti-competitive markets. Through historical, contextual, and empirical analysis, the Article describes the state of Hollywood motion-picture distributionfrom its anti- competitive beginnings through the industry's role in creating an anti-competitive, racially divided market at the end of the last century. The Article's evidence suggests that race-based inefficiencies have plagued the film distribution process and such inefficiencies might likely be caused by the anti-competitive structure of the market itself, and not merely by overt or intentional racial-discrimination.After explaining why traditional anti-discrimination laws are ineffective remedies for such inefficiencies, the Article asks whether antitrust remedies and market mechanisms mght provide more robust solutions. -

Microsoft Office Outlook

Barnes, Britianey From: Michael Glees [[email protected]] Sent: Wednesday, April 30, 2014 11:53 AM To: Luehrs, Dawn; Barnes, Britianey; Curtis, June; Clausen, Janel; Hastings, Douglas Cc: Juliana Selfridge Subject: "Wheel of Fortune" (Season 32) - Updated Cast Insurance Log Attachments: Cast Log.Wheel of Fortune (Season 32).xls Categories: Red Category Hello, Attached & below for your reference/review is the updated cast insurance log for "Wheel of Fortune”. Please keep us advised of any additional artists/roles (including artists start date) you wish to declare on this production. Thank you! CAST LOG To: Dawn Luehrs Updated: 4/30/2014 From: Michael Glees Carrier: Fireman's Fund Title: "Wheel of Fortune" (Season 32) Policy No.: MPT07109977 Insured: Sony Pictures Entertainment Inc. Start Date: 5/1/2014 PP Dates: 5/1/14 Description: TV Game Show Accident Only Medical Coverage Covered Artist Role Coverage Effective Start Date Effective Restrictions/Special Terms 1 Pat Sajak Host 4/29/2014 2 Vanna White Host 4/29/2014 3 Bob Cisneros Director 4/29/2014 4 Harry Friedman Exec. Producer 4/29/2014 5 Steve Schwartz Supervising Producer 4/29/2014 6 Jim Thornton Announcer 4/29/2014 7 Randy Berke Line Producer 4/29/2014 8 Robert Sofia Coordinating Producer 4/29/2014 9 Karen Griffith Supervising Producer 4/29/2014 10 Robert Roman Producer 4/29/2014 11 Amanda Stern Producer 4/29/2014 12 Brooke Eaton Producer 4/29/2014 13 Patrick Obrien Associate Director/Producer 4/29/2014 14 Bob Ennis Technical Director 4/29/2014 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 1 22 23 24 25 Michael Glees | Account Specialist Aon/Albert G. -

Sundayiournal

STANDING STRONG FOR 1,459 DAYS — THE FIGHT'S NOT OVER YET JULY 11-17, 1999 THE DETROIT VOL. 4 NO. 34 75 CENTS S u n d a yIo u r n a l PUBLISHED BY LOCKED-OUT DETROIT NEWSPAPER WORKERS ©TDSJ JIM WEST/Special to the Journal Nicholle Murphy’s support for her grandmother, Teamster Meka Murphy, has been unflagging. Marching fourward Come Tuesday, it will be four yearsstrong and determined. In this editionOwens’ editorial points out the facthave shown up. We hope that we will since the day in July of 1995 that ofour the Sunday Journal, co-editor Susanthat the workers are in this strugglehave contracts before we have to put Detroit newspaper unions were forcedWatson muses on the times of happiuntil the end and we are not goingtogether any another anniversary edition. to go on strike. Although the companess and joy, in her Strike Diarywhere. on On Pages 19-22 we show offBut four years or 40, with your help, nies tried mightily, they never Pagedid 3. Starting on Page 4, we putmembers the in our annual Family Albumsolidarity and support, we will be here, break us. Four years after pickingevents up of the struggle on the record.and also give you a glimpse of somestanding of strong. our first picket signs, we remainOn Page 10, locked-out worker Keiththe far-flung places where lawn signs— Sunday Journal staff PAGE 10 JULY 11 1999 Co-editors:Susan Watson, Jim McFarlin --------------------- Managing Editor: Emily Everett General Manager: Tom Schram Published by Detroit Sunday Journal Inc. -

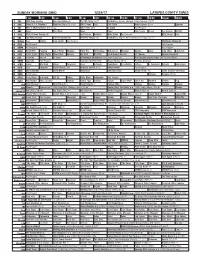

Sunday Morning Grid 12/24/17 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 12/24/17 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Los Angeles Chargers at New York Jets. (N) Å 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) NBC4 News Paid PGA TOUR Action Sports (N) Å Spartan 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News News Jack Hanna Ocean Sea Rescue Wildlife 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 11 FOX Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Kickoff (N) FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Los Angeles Rams at Tennessee Titans. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Matter Fred Jordan Paid Program Christmas Miracle at 18 KSCI Paid Program Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Milk Street Mexican Martha Jazzy Julia Child Chefs Life 28 KCET 1001 Nights 1001 Nights Mixed Nutz Edisons Biz Kid$ Biz Kid$ 53rd Annual Wassail St. Thomas Holiday Handbells 30 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch A Firehouse Christmas (2016) Anna Hutchison. The Spruces and the Pines (2017) Jonna Walsh. 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Grandma Got Run Over Netas Divinas (TV14) Premios Juventud 40 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Jeffress K. -

Mar 01, 2013 VANNA WHITE, Plaintiff-Appellant, V. SAMSUNG

Page 1 Caution As of: Mar 01, 2013 VANNA WHITE, Plaintiff-Appellant, v. SAMSUNG ELECTRONICS AMERICA, INC.; DAVID DEUTSCH ASSOCIATES, Defendants-Appellees. No. 90-55840 UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT 989 F.2d 1512; 1993 U.S. App. LEXIS 4928; 26 U.S.P.Q.2D (BNA) 1362; 21 Media L. Rep. 1330; 93 Cal. Daily Op. Service 1933; 93 Daily Journal DAR 3477 March 18, 1993, Filed PRIOR HISTORY: [**1] D.C. No. The petition for rehearing is DENIED and the sug- CV-88-6499-RSL. gestion for rehearing en banc is REJECTED. Original Opinion Reported at 1992 U.S. App. LEXIS 17205 DISSENT BY: KOZINSKI Amended Opinion Reported at 1992 U.S. App. DISSENT LEXIS 19253. DISSENT JUDGES: Before: Alfred T. Goodwin, Harry Pregerson KOZINSKI, Circuit Judge, with whom Circuit and Arthur L. Alarcon, Circuit Judges.Dissent by Judge Judges O'SCANNLAIN and KLEINFELD join, dissent- Kozinski. ing from the order rejecting the suggestion for rehearing en banc. OPINION I [*1512] ORDER AND DISSENT Saddam Hussein wants to keep advertisers from us- ORDER ing his picture [**2] in unflattering contexts. 1 Clint The panel has voted unanimously to deny the peti- Eastwood doesn't want tabloids to write about him. 2 tion for rehearing. Judge Pregerson has voted to reject Rudolf Valentino's heirs want to control his film biog- the suggestion for rehearing en banc, and Judge Goodwin raphy. 3 The Girl Scouts don't want their image soiled by so recommends. Judge Alarcon has voted to accept the association with certain activities. -

Limiting a Celebrity's Right to Publicity Todd J

Santa Clara Law Review Volume 35 | Number 2 Article 11 1-1-1995 The oP wer to Control Identity: Limiting a Celebrity's Right to Publicity Todd J. Rahimi Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.law.scu.edu/lawreview Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Todd J. Rahimi, Comment, The Power to Control Identity: Limiting a Celebrity's Right to Publicity, 35 Santa Clara L. Rev. 725 (1995). Available at: http://digitalcommons.law.scu.edu/lawreview/vol35/iss2/11 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Santa Clara Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Santa Clara Law Review by an authorized administrator of Santa Clara Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE POWER TO CONTROL IDENTITY: LIMITING A CELEBRITY'S RIGHT TO PUBLICITY I. INTRODUCTION In a recent series of television commercials, tennis star Andre Agassi says that "Image is everything."' Most celebri- ties would probably agree with this statement, along with the notion that nothing is more important than the right to con- trol their image. In California, as in a vast majority of juris- dictions, the ability to control one's image is accomplished by protecting against the commercial appropriation of one's identity.2 Courts and commentators have differed as to whether this legal protection falls under a theory of "privacy," "property," or "publicity," but all agree that the interest exists and deserves protection.3 As the influence of the media grows increasingly perva- sive in society, however, the question of how to protect this interest becomes more troublesome. -

SHSU Video Archive Basic Inventory List Department of Library Science

SHSU Video Archive Basic Inventory List Department of Library Science A & E: The Songmakers Collection, Volume One – Hitmakers: The Teens Who Stole Pop Music. c2001. A & E: The Songmakers Collection, Volume One – Dionne Warwick: Don’t Make Me Over. c2001. A & E: The Songmakers Collection, Volume Two – Bobby Darin. c2001. A & E: The Songmakers Collection, Volume Two – [1] Leiber & Stoller; [2] Burt Bacharach. c2001. A & E Top 10. Show #109 – Fads, with commercial blacks. Broadcast 11/18/99. (Weller Grossman Productions) A & E, USA, Channel 13-Houston Segments. Sally Cruikshank cartoon, Jukeboxes, Popular Culture Collection – Jesse Jones Library Abbott & Costello In Hollywood. c1945. ABC News Nightline: John Lennon Murdered; Tuesday, December 9, 1980. (MPI Home Video) ABC News Nightline: Porn Rock; September 14, 1985. Interview with Frank Zappa and Donny Osmond. Abe Lincoln In Illinois. 1939. Raymond Massey, Gene Lockhart, Ruth Gordon. John Ford, director. (Nostalgia Merchant) The Abominable Dr. Phibes. 1971. Vincent Price, Joseph Cotton. Above The Rim. 1994. Duane Martin, Tupac Shakur, Leon. (New Line) Abraham Lincoln. 1930. Walter Huston, Una Merkel. D.W. Griffith, director. (KVC Entertaiment) Absolute Power. 1996. Clint Eastwood, Gene Hackman, Laura Linney. (Castle Rock Entertainment) The Abyss, Part 1 [Wide Screen Edition]. 1989. Ed Harris. (20th Century Fox) The Abyss, Part 2 [Wide Screen Edition]. 1989. Ed Harris. (20th Century Fox) The Abyss. 1989. (20th Century Fox) Includes: [1] documentary; [2] scripts. The Abyss. 1989. (20th Century Fox) Includes: scripts; special materials. The Abyss. 1989. (20th Century Fox) Includes: special features – I. The Abyss. 1989. (20th Century Fox) Includes: special features – II. Academy Award Winners: Animated Short Films. -

Torts - White V

Golden Gate University Law Review Volume 23 Article 20 Issue 1 Ninth Circuit Survey January 1993 Torts - White v. Samsung Electronics America, Inc.: The Wheels of Justice Take an Unfortunate Turn John F. Hyland Ted C. Lindquist III Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.law.ggu.edu/ggulrev Part of the Civil Law Commons Recommended Citation John F. Hyland and Ted C. Lindquist III, Torts - White v. Samsung Electronics America, Inc.: The Wheels of Justice Take an Unfortunate Turn, 23 Golden Gate U. L. Rev. (1993). http://digitalcommons.law.ggu.edu/ggulrev/vol23/iss1/20 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Academic Journals at GGU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Golden Gate University Law Review by an authorized administrator of GGU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Hyland and Lindquist: Torts TORTS WHITE v. SAMSUNG ELECTRONICS AMERICA, INC.: THE WHEELS OF JUSTICE TAKE AN UNFORTUNATE TURN I. INTRODUCTION The Ninth Circuit's decision in White v. Samsung Electron ics America, Inc./ greatly 'expands the protection afforded to an individual's right of publicity under California common law2 and Federal statutory law. s In White, the Ninth Circuit held that an advertisement depicting a robot dressed in a wig, gown and jew elry, while posed next to a game board," did not bear a sufficient likeness to Plaintiff Vanna White to constitute an appropriation of her identity under California Civil Code section 3344. 11 How ever, the court ruled that this same advertisement may be a vio lation of White's common law right of publicity.s The court re manded the case so that the issue could be submitted to a jury.7 Similarly, the court remanded White's claim under section 43(a) of the Lanltam Act,8 ruling that White had raised a genuine is sue of material fact concerning a likelihood of confusion as to 1. -

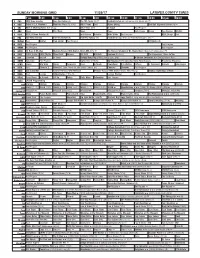

Sunday Morning Grid 11/26/17 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 11/26/17 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Buffalo Bills at Kansas City Chiefs. (N) Å 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) NBC4 News Paid Alpine Skiing Red Bull Signature Series (N) Å 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News News Jack Hanna Ocean Sea Rescue Wildlife 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 11 FOX Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Kickoff (N) FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Chicago Bears at Philadelphia Eagles. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Matter Fred Jordan Paid Program 89 Blocks (N) 18 KSCI Paid Program Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR I’ll Have It My Way Memory Rescue With Daniel Amen, MD (TVG) Å The Forever Wisdom of Dr. Wayne Dyer Tribute to Dr. Wayne Dyer. Å 28 KCET 1001 Nights 1001 Nights Mixed Nutz Edisons Biz Kid$ Biz Kid$ Santana IV (TV14) The Carpenters: Close to You 30 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Holiday Road Trip (2013) Ashley Scott. (PG) A Golden Christmas ›› (2009) Andrea Roth. 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Como Dice el Dicho Sor Tequila (1977, Comedia) María Elena Velasco. República Deportiva 40 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Jeffress K. -

Wheel of Fortune Play Pictionary Would You Rather Scattegories Family Feud Just Dance! Virtual Bingo! Fake Artist Online Calling

Socialization Choice Board -Online Group Fun Being social with friends helps students learn social norms. It’s important for our mental health. Play these online games with students to build a positive online community culture. Just click and pop it on your screen share! Writing Passions Science/Social = ELA/ Reading Math Wellness & Physical Activity Creativity Wheel of Fortune Play Pictionary Would You Rather Play this Pictionary game in your own private Take a guess at this puzzle with your chat room. Give the kids the link and they Ask questions for the kids with two students and take a spin on the will be able to join in. Student be warned options. Would you rather eat a bowl of wheel. Be your own Vanna White. you need to be able to spell the clues to get worms or a bowl of ants? There are sure Enjoy this game. the points! A very fun competitive Game for to be some laughs over their Middle Years. Leave on your video call for justifications of their choices. Great some fun commentary about the teacher’s drawings!! debates are sure to occur! Scattegories Family Feud Just Dance! Have some fun with this classic letter Take a guess at this puzzle with your Go on Youtube and Screen Share your – word association game! Screen students. Split them up into two groups favourite dance. OR sign up here, share this online game and have beforehand and take turns giving download the app and open up your students share their answers answers. Make sure to screen share. -

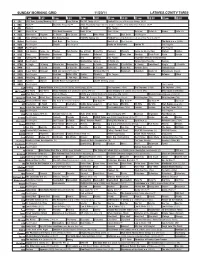

Sunday Morning Grid 11/20/11 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 11/20/11 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Morning (N) Å Face/Nation The NFL Today (N) Å Football Raiders at Minnesota Vikings. (N) Å 4 NBC News Å Meet the Press (N) Å 2011 Presidents Cup Final Day. Singles matches. From Melbourne, Australia. (N) Å 5 CW News Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week-Amanpour News (N) Å News (N) Å News Å Vista L.A. Heroes Vista L.A. 9 KCAL Tomorrow’s Kingdom K. Shook Joel Osteen Prince Mike Webb Paid Best Deals Paid Program 11 FOX Hour of Power (N) (TVG) Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Tampa Bay Buccaneers at Green Bay Packers. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program Best Buys Paid Program Best of L.A. Paid Program The Hoax ››› (2006) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Paid Program Hecho en Guatemala Iranian TV Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Sid Science Curios -ity Thomas Bob Builder Joy of Paint Paint This Dewberry Wyland’s Home for Christy Rost Kitchen Kitchen 28 KCET Cons. Wubbulous Busytown Peep Pancakes Pufnstuf Lidsville Place, Own Roadtrip Chefs Field Pépin Venetia 30 ION Turning Pnt. Discovery In Touch Paid Beyond Paid Program Inspiration Ministry Campmeeting 34 KMEX Paid Program Muchachitas Como Tu Al Punto (N) Aurora Valle Presenta... Vecinos 40 KTBN K. Hagin Ed Young Miracle-You Redemption Love In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. -

The Ithacan, 1993-01-28

Ithaca College Digital Commons @ IC The thI acan, 1992-93 The thI acan: 1990/91 to 1999/2000 1-28-1993 The thI acan, 1993-01-28 Ithaca College Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/ithacan_1992-93 Recommended Citation Ithaca College, "The thI acan, 1993-01-28" (1993). The Ithacan, 1992-93. 16. http://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/ithacan_1992-93/16 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the The thI acan: 1990/91 to 1999/2000 at Digital Commons @ IC. It has been accepted for inclusion in The thI acan, 1992-93 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ IC. Opinion Arts, Entertainment Sports Index Open up! Images of poetry Sudden death Opinion ................................. 8 The men's basketball team Board of Trustees should Handwerk.er showcases 11 · '~ t:· -::; .,q ~~~;~~r::;i~~t.·.·:.·.·.-.·::.·.·.·.·.·N photographer's travels loses in overtime to Hilbert , ; Classifieds/Comics ............. 18 have truly 'open' meeting .JL J,,. 1 :. ::.-:_. .... • -., Sports ................................. 21 The ITHACAN The Newspaper For The Ithaca College Community Vol. 60, No.16 Thursday, January 28, 1993 28 pages Free Cleaning up Proposed budget increase lowest in nearly a decade Downturn may suggest modest tuition hike By Tom Arundel If budget increases reflect tuition increases at Ithaca College as they have in the past, the "Although we expect tuition to increase in student tuition for 1993-94 should increase, we have fewer stu be minimal. But nothing is definite. dents and consequently the The proposed overall operating budget increase for 1993-94 is four percent, the overall rate of increase in the e Ithacan/ Gregory Di Bernardo lowest in over a decade, according to John College's budget will slow Ithaca College dlaposed of chemlcals In this clearlng next to the accen road Galt, director of budget behind Park Hall.