Improving Access to Banking: Evidence from Kenya

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bank Code Finder

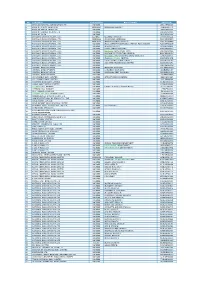

No Institution City Heading Branch Name Swift Code 1 AFRICAN BANKING CORPORATION LTD NAIROBI ABCLKENAXXX 2 BANK OF AFRICA KENYA LTD MOMBASA (MOMBASA BRANCH) AFRIKENX002 3 BANK OF AFRICA KENYA LTD NAIROBI AFRIKENXXXX 4 BANK OF BARODA (KENYA) LTD NAIROBI BARBKENAXXX 5 BANK OF INDIA NAIROBI BKIDKENAXXX 6 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. ELDORET (ELDORET BRANCH) BARCKENXELD 7 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. MOMBASA (DIGO ROAD MOMBASA) BARCKENXMDR 8 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. MOMBASA (NKRUMAH ROAD BRANCH) BARCKENXMNR 9 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. NAIROBI (BACK OFFICE PROCESSING CENTRE, BANK HOUSE) BARCKENXOCB 10 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. NAIROBI (BARCLAYTRUST) BARCKENXBIS 11 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. NAIROBI (CARD CENTRE NAIROBI) BARCKENXNCC 12 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. NAIROBI (DEALERS DEPARTMENT H/O) BARCKENXDLR 13 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. NAIROBI (NAIROBI DISTRIBUTION CENTRE) BARCKENXNDC 14 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. NAIROBI (PAYMENTS AND INTERNATIONAL SERVICES) BARCKENXPIS 15 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. NAIROBI (PLAZA BUSINESS CENTRE) BARCKENXNPB 16 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. NAIROBI (TRADE PROCESSING CENTRE) BARCKENXTPC 17 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. NAIROBI (VOUCHER PROCESSING CENTRE) BARCKENXVPC 18 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. NAIROBI BARCKENXXXX 19 CENTRAL BANK OF KENYA NAIROBI (BANKING DIVISION) CBKEKENXBKG 20 CENTRAL BANK OF KENYA NAIROBI (CURRENCY DIVISION) CBKEKENXCNY 21 CENTRAL BANK OF KENYA NAIROBI (NATIONAL DEBT DIVISION) CBKEKENXNDO 22 CENTRAL BANK OF KENYA NAIROBI CBKEKENXXXX 23 CFC STANBIC BANK LIMITED NAIROBI (STRUCTURED PAYMENTS) SBICKENXSSP 24 CFC STANBIC BANK LIMITED NAIROBI SBICKENXXXX 25 CHARTERHOUSE BANK LIMITED NAIROBI CHBLKENXXXX 26 CHASE BANK (KENYA) LIMITED NAIROBI CKENKENAXXX 27 CITIBANK N.A. NAIROBI NAIROBI (TRADE SERVICES DEPARTMENT) CITIKENATRD 28 CITIBANK N.A. -

ANNUAL REPORT and Financial Statements

2014 ANNUAL REPORT and Financial Statements Contents1 Board members and committees 2 Senior Management and Management Committees 4 Corporate information 6 Corporate governance statement 8 Director’s report 10 Statement of directors’ responsibilities 11 Report of the independent auditors 12 Statement of profit or loss and other comprehensive income 13 Statement of financial position 14 Statement of changes in equity 15 Statement of cash flows 16 Notes to the financial statements 17 Board Members and Committees 2 Directors Mr. Akif H. Butt Ms. Shiru Mwangi Non Executive Director Non Executive Director Christine Sabwa Mr. Robert Shibutse Non Executive Director Executive Director Mr. Martin Ernest Mr. Abdulali Kurji Non Executive Director Non Executive Director Mr. Sammy A. S. Itemere Ms. Jacqueline Hinga Managing Director Head-Governance & Company Secretary Mr. Dan Ameyo, MBS, OGW - Chairman of the Board Mr. Dan Ameyo serves as the Chairman of Equatorial Commercial Bank Limited. He is a practicing advocate and legal consultant on trade and integration law in Kenya and within the East African Community and COMESA region. Mr. Ameyo serves as Director of Mumias Sugar Company Limited. He is an advocate of the High Court of Kenya, a member of the Law Society of Kenya (LSK) and a Fellow of the Chartered Institute of Arbitrators in London. He served as a State Counsel in the Attorney General’s chambers. He also served as the Post Master General and Chief Executive Officer of Postal Corporation of Kenya. Mr. Ameyo holds a Bachelor of Laws (LL.B) (Hons) Degree from the University of Nairobi and a Master of Laws (LL.M) from Queen Mary, University of London. -

KDIC Annual Report 2018

ANNUAL REPORT 2017 - 2018 ANNUAL REPORT AND FINANCIAL STATEMENTS FOR THE FINANCIAL YEAR ENDED JUNE 30, 2018 Prepared in accordance with the Accrual Basis of Accounting Method under the International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) CONTENTS Key Entity Information..........................................................................................................1 Directors and statutory information......................................................................................3 Statement from the Board of Directors.................................................................................11 Report of the Chief Executive Officer...................................................................................12 Corporate Governance statement........................................................................................15 Management Discussion and Analysis..................................................................................19 Corporate Social Responsibility...........................................................................................27 Report of the Directors.......................................................................................................29 Statement of Directors' Responsibilities................................................................................30 Independent Auditors' Report.............................................................................................31 Financial Statements: Statement of Profit or Loss and other Comprehensive Income...................................35 -

Njuguna Ndung'u: Recent Financial Sector Performance in Kenya

Njuguna Ndung’u: Recent financial sector performance in Kenya Remarks by Prof. Njuguna Ndung’u, Governor of the Central Bank of Kenya, on the occasion of the 50th anniversary celebrations for NIC Bank Limited, Nairobi, 18 November 2009. * * * Mr. James Ndegwa, Chairman of the Board of Directors of NIC Bank; Mr. James Macharia, Group Managing Director and Chief Executive Officer of NIC Bank; Board Members here present; Staff of NIC Bank; Distinguished Guests; Ladies and Gentlemen: I am delighted to be here this evening to join NIC Bank in celebrating fifty years of providing financial services to Kenyans. Today indeed marks yet another landmark event on NIC’s successful path. I am therefore grateful for the invitation to join this joyous occasion. Let me at this early juncture commend the Board, Management and Staff of NIC Bank for successfully serving Kenyans for the last 50 years. • I am informed that NIC Bank (formerly National Industrial Credit Bank Limited) was incorporated in Kenya on September 29, 1959 and started off as a non-bank financial institution providing hire purchase and instalment facilities. The institution became a public company in 1971 and was listed at the Nairobi Stock Exchange. In its quest to meet the growing customer needs in terms of diverse banking requirements, NIC Bank converted to a commercial bank and obtained its banking licence in 1995. In November 1997, the bank merged with African Mercantile Bank Limited (AmBank) which allowed the bank to enhance its position in the sector. Since then, the bank has grown significantly. • Currently the bank has 15 branches countrywide having opened two branches in Kisumu and Thika in the last one year while the Meru branch is scheduled to be opened before the end of this year. -

2 Giro Commercial Bank Ltd Was Acquired by I&M Bank Limited

COMMERCIAL BANKS WEIGHTED AVERAGE LENDING RATES PER LOAN CATEGORY AND MATURITY (%) Loan Category PERSONAL BUSINESS CORPORATE OVERALL RATES Loan Maturity Overdraft 1-5 Years Over 5 years Overdraft 1-5 Years Over 5 years Overdraft 1-5 Years Over 5 years 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 Banks Dec-16 Mar-171 Jun-171 Dec-16 Mar-171 Jun-171 Dec-16 Mar-171 Jun-171 Dec-16 Mar-171 Jun-171 Dec-16 Mar-171 Jun-171 Dec-16 Mar-171 Jun-171 Dec-16 Mar-171 Jun-171 Dec-16 Mar-171 Jun-171 Dec-16 Mar-171 Jun-171 Dec-16 Mar-171 Jun-171 1 Africa Banking Corporation Ltd 14.1 13.5 13.1 14.0 13.1 13.7 13.9 13.7 13.9 14.2 12.8 13.7 14.1 13.2 13.8 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.3 13.5 13.7 14.1 12.0 13.70 14.0 13.3 13.7 14.1 13.1 13.7 2 Bank of Africa Kenya Ltd 14.0 14.0 14.0 13.9 13.9 13.9 14.0 14.0 14.0 13.9 13.9 13.9 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 13.8 14.0 14.0 13.8 13.8 13.75 14.0 14.0 14.0 13.9 13.9 13.9 3 Bank of Baroda (K) Ltd 14.0 13.8 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 13.9 13.9 13.9 13.9 13.9 13.9 14.0 14.0 14.0 13.9 13.9 13.9 13.9 13.9 13.93 14.0 14.0 14.0 13.9 13.9 13.9 4 Bank of India 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.00 14.0 14.0 13.9 14.0 14.0 14.0 5 Barclays Bank of Kenya Ltd 14.0 14.0 13.5 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 13.8 13.4 13.5 14.0 13.8 13.9 13.8 13.4 13.7 13.7 13.6 12.7 13.4 13.3 13.33 13.6 13.4 13.5 13.8 13.7 13.8 6 Stanbic Bank Kenya Ltd 13.9 13.8 10.3 13.9 13.8 13.6 13.9 13.9 13.6 12.6 13.7 10.2 13.9 13.9 13.4 13.7 13.8 13.9 12.3 12.7 10.3 13.3 13.3 13.97 14.0 14.0 14.0 13.3 13.6 -

Money Transfer Systems: the Practice and Potential for Products in Kenya

Shelter Afrique Building, Mamlaka Road MicroSave-Africa P.O. Box 76436, Nairobi, Kenya Tel: 254 2 2724801/2724806/2726397 An Initiative of Austria/CGAP/DFID/UNDP Fax: 254 2 2720133 Website: www.MicroSave-Africa.com Email: [email protected] PASSING THE BUCK Money Transfer Systems: The Practice and Potential for Products in Kenya Kamau Kabbucho, Cerstin Sander and Peter Mukwana May 2003 PASSING THE BUCK: Money Transfer Systems: The Practice and Potential for Products in Kenya i Kamau Kabbucho, Cerstin Sander and Peter Mukwana Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................................IV BACKGROUND ................................................................................................................................................................ IV SUMMARY OF FINDINGS ................................................................................................................................................. IV STRUCTURE OF THE REPORT........................................................................................................................................... VI INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................................ 1 BACKGROUND AND OBJECTIVES ..................................................................................................................................... 1 -

Automated Clearing House Participants Bank / Branches Report

Automated Clearing House Participants Bank / Branches Report 21/06/2017 Bank: 01 Kenya Commercial Bank Limited (Clearing centre: 01) Branch code Branch name 091 Eastleigh 092 KCB CPC 094 Head Office 095 Wote 096 Head Office Finance 100 Moi Avenue Nairobi 101 Kipande House 102 Treasury Sq Mombasa 103 Nakuru 104 Kicc 105 Kisumu 106 Kericho 107 Tom Mboya 108 Thika 109 Eldoret 110 Kakamega 111 Kilindini Mombasa 112 Nyeri 113 Industrial Area Nairobi 114 River Road 115 Muranga 116 Embu 117 Kangema 119 Kiambu 120 Karatina 121 Siaya 122 Nyahururu 123 Meru 124 Mumias 125 Nanyuki 127 Moyale 129 Kikuyu 130 Tala 131 Kajiado 133 KCB Custody services 134 Matuu 135 Kitui 136 Mvita 137 Jogoo Rd Nairobi 139 Card Centre Page 1 of 42 Bank / Branches Report 21/06/2017 140 Marsabit 141 Sarit Centre 142 Loitokitok 143 Nandi Hills 144 Lodwar 145 Un Gigiri 146 Hola 147 Ruiru 148 Mwingi 149 Kitale 150 Mandera 151 Kapenguria 152 Kabarnet 153 Wajir 154 Maralal 155 Limuru 157 Ukunda 158 Iten 159 Gilgil 161 Ongata Rongai 162 Kitengela 163 Eldama Ravine 164 Kibwezi 166 Kapsabet 167 University Way 168 KCB Eldoret West 169 Garissa 173 Lamu 174 Kilifi 175 Milimani 176 Nyamira 177 Mukuruweini 180 Village Market 181 Bomet 183 Mbale 184 Narok 185 Othaya 186 Voi 188 Webuye 189 Sotik 190 Naivasha 191 Kisii 192 Migori 193 Githunguri Page 2 of 42 Bank / Branches Report 21/06/2017 194 Machakos 195 Kerugoya 196 Chuka 197 Bungoma 198 Wundanyi 199 Malindi 201 Capital Hill 202 Karen 203 Lokichogio 204 Gateway Msa Road 205 Buruburu 206 Chogoria 207 Kangare 208 Kianyaga 209 Nkubu 210 -

Bank Supervision Annual Report 2019 1 Table of Contents

CENTRAL BANK OF KENYA BANK SUPERVISION ANNUAL REPORT 2019 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS VISION STATEMENT VII THE BANK’S MISSION VII MISSION OF BANK SUPERVISION DEPARTMENT VII THE BANK’S CORE VALUES VII GOVERNOR’S MESSAGE IX FOREWORD BY DIRECTOR, BANK SUPERVISION X EXECUTIVE SUMMARY XII CHAPTER ONE STRUCTURE OF THE BANKING SECTOR 1.1 The Banking Sector 2 1.2 Ownership and Asset Base of Commercial Banks 4 1.3 Distribution of Commercial Banks Branches 5 1.4 Commercial Banks Market Share Analysis 5 1.5 Automated Teller Machines (ATMs) 7 1.6 Asset Base of Microfinance Banks 7 1.7 Microfinance Banks Market Share Analysis 9 1.8 Distribution of Foreign Exchange Bureaus 11 CHAPTER TWO DEVELOPMENTS IN THE BANKING SECTOR 2.1 Introduction 13 2.2 Banking Sector Charter 13 2.3 Demonetization 13 2.4 Legal and Regulatory Framework 13 2.5 Consolidations, Mergers and Acquisitions, New Entrants 13 2.6 Medium, Small and Micro-Enterprises (MSME) Support 14 2.7 Developments in Information and Communication Technology 14 2.8 Mobile Phone Financial Services 22 2.9 New Products 23 2.10 Operations of Representative Offices of Authorized Foreign Financial Institutions 23 2.11 Surveys 2019 24 2.12 Innovative MSME Products by Banks 27 2.13 Employment Trend in the Banking Sector 27 2.14 Future Outlook 28 CENTRAL BANK OF KENYA 2 BANK SUPERVISION ANNUAL REPORT 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER THREE MACROECONOMIC CONDITIONS AND BANKING SECTOR PERFORMANCE 3.1 Global Economic Conditions 30 3.2 Regional Economy 31 3.3 Domestic Economy 31 3.4 Inflation 33 3.5 Exchange Rates 33 3.6 Interest -

Credit Risk and Financial Performance of Banks Listed at the Nairobi Securities Exchange, Kenya

International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences Vol. 9 , No. 1, Jan, 2019, E-ISSN: 2222 -6990 © 2018 HRMARS Credit Risk and Financial Performance of Banks Listed at the Nairobi Securities Exchange, Kenya Isabwa Harwood Kajirwa & Nelima Wambaya Katherine To Link this Article: http://dx.doi.org/10.6007/IJARBSS/v9-i1/5407 DOI: 10.6007/IJARBSS/v9-i1/5407 Received: 19 Dec 2018, Revised: 14 Jan 2019, Accepted: 23 Jan 2019 Published Online: 28 Jan 2019 In-Text Citation: (Kajirwa & Katherine, 2019) To Cite this Article: Kajirwa, I. H., & Katherine, N. W. (2019). Credit Risk and Financial Performance of Banks Listed at the Nairobi Securities Exchange, Kenya. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 9(1), 400–413. Copyright: © 2019 The Author(s) Published by Human Resource Management Academic Research Society (www.hrmars.com) This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license. Anyone may reproduce, distribute, translate and create derivative works of this article (for both commercial and non-commercial purposes), subject to full attribution to the original publication and authors. The full terms of this license may be seen at: http://creativecommons.org/licences/by/4.0/legalcode Vol. 9, No. 1, 2019, Pg. 400 - 413 http://hrmars.com/index.php/pages/detail/IJARBSS JOURNAL HOMEPAGE Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://hrmars.com/index.php/pages/detail/publication-ethics 400 International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences Vol. 9 , No. 1, Jan, 2019, E-ISSN: 2222 -6990 © 2018 HRMARS Credit Risk and Financial Performance of Banks Listed at the Nairobi Securities Exchange, Kenya Isabwa Harwood Kajirwa1 Nelima Wambaya Katherine2 1,2Department of Business Management, University of Eldoret, P.O. -

An Analysis of the Usefulness of Annual Financial Statements to Credit Risk Analysts in Kenyan Commercial Banks

An Analysis Of The Usefulness Of Annual Financial Statements To Credit Risk Analysts In Kenyan Commercial Banks / Adam M. Boru Supervisor Luther Otieno A management research project submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Masters in Business Administration of the University of Nairobi. August 2003 DECLARATION This research is my original work and has not been presented for a degree in any other University. Signed Date " 7 — I I ' X O O ^ Adam Mohamed Boru D61/P/8801/98 Candidate 0WV£!?srrv op MAIROb. i n w p o v A e p rp I I& R a Q' This research has been submitted for examination with my approval as the university supervisor. Signed Date 7 - 1 ^ Mr. Luther Otieno Odhiambo Lecturer Department of Accounting Faculty of Commerce University of Nairobi (i) acknowledgements May I first and foremost thank my supervisor Mr. Luther Otieno Odhiambo for his confidence-inspiring and enthusiastic support. May I also thank my fellow MBA students for their support throughout the course. Special thanks to Matu Mugo, Linda Kamau, J. Oltetia, John Musau, Dan Obiero, Joyce Mutanu, Chris Otieno and T.K. Kimutai. Dulacha B. Galgalo, a PHD student at the University of Western Australia, Perth, also deserves a special mention for his encouragement and untiring support. Last but not least, to all who supported me in one way or the other, I am most grateful. UNIVERSITY of MAIRUu. UOWER KABETE Li&^Arv (ii) DEDICATION This project is dedicated to my parents who leant the hard way that lack of formal education in today’s world is a handicap and ensured that I avoided the pitfall. -

East Africa's Family-Owned Business Landscape

EAST AFRICA’S FAMILY-OWNED BUSINESS LANDSCAPE 500 LEADING COMPANIES ACROSS THE REGION PREMIUM SPONSORS: 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS EAST AFRICA’S FAMILY-OWNED BUSINESS CONTENTS LANDSCAPE Co-Founder, CEO 3 Executive Summary Rob Withagen 4 Methodology Co-Founder, COO Greg Cohen 7 1. MARKET LANDSCAPE Project Director 8 Regional Heavyweight: East Africa Leads Aicha Daho Growth Across the Continent Content Director 10 Come Together: Developing Intra- Jennie Forcier Patterson Regional Trade Opens Markets of Data Director Significant Scale Yusra Khadra 11 Interview: Banque du Caire Editorial Manager Lauren Mellows 13 2. FOB THEMES Research & Data Team Alexandria Akena 14 Stronger Together: Private Equity Jerome Amedo Offers Route to Growth for Businesses Laban Bore Prepared to Cede Some Ownership Jessen Chiniven Control Woyneab Habte Mayowa Hambolu 15 Interview: Centum Investment Milkiyas Lekeleh Siyum 16 Interview: Nairobi Securities Exchange Omololu Adeniran 17 A Hire Calling: Merit is Becoming a Medina Mamadou Stronger Factor in FOB Employment Kuringe Masao Melina Matabishi Practices Ivan Matoowa 18 Interview: Anjarwalla & Khanna Sweetness Mathew 21 Interview: CDC Group Plc Paige Arhaus Theodore Angwenyi 22 Interview: Melvin Marsh International Design 23 Planning for the Future: Putting Next- Nuno Caldeira Generation Leaders at the Helm 24 Interview: Britania Allied Industries 25 3. COUNTRY DEEPDIVES 25 Kenya 45 Ethiopia 61 Uganda 77 Tanzania 85 Rwanda 91 4. FOB DIRECTORY EAST AFRICA’S FAMILY-OWNED BUSINESS LANDSCAPE EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 EXECUTIVE -

Effect of Mobile Banking on Cost Efficiency Of

EFFECT OF MOBILE BANKING ON COST EFFICIENCY OF COMMERCIAL BANKS IN KENYA WILLY WACHIRA MUTHII A RESEARCH PROJECT SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN FINANCE, SCHOOL OF BUSINESS, UNIVERSITY OF NAIROBI OCTOBER, 2019 DECLARATION I, the undersigned, declare that this is my original work and has not been presented to any institution or university other than the University of Nairobi for examination. Signed: _____________________Date: __________________________ WILLY WACHIRA MUTHII D63/64566/2013 This research project has been submitted for examination with my approval as the University Supervisor. Signed: _____________________Date: __________________________ DR. CYRUS IRAYA Department of Finance and Accounting School of Business, University of Nairobi ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Quoting the words of Shannon L Adler, "When you invite people to share in your miracle, you create future allies during rough weather". This quote is a true reflection of my journey writing this research project because without the individuals involved, this journey would have been impossible. A sincere thank you goes to my supervisor Dr. Cyrus Iraya for his patience, support and guidance. For believing in my project and offering his insight and expertise in this field. For not hesitating to share his thoughts and views enabling me to be where I am today. A special thank you to Mr. Murage for his guidance and support throughout this process. Finally I would like to thank my colleagues and friends who were there to offer me support and listen to me and my views while writing this research project. They encouraged me to never give up and for that I will forever be grateful.