The Hopeless University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

19Th MEETING of the IICWG

th 19 MEETING OF THE INTERNATIONAL ICE CHARTING WORKING GROUP September 24-28, 2018 – Helsinki, Finland AGENDA – Draft 6 “Ice Information for Navigating the Sub-Polar Seas” MONDAY, SEPTEMBER 24 Plenary Sessions will be held in “Brainstorm” 08:30 – 09:00 Registration 09:00 – 09:45 Official Meeting Opening Co-Chairs 09:00 – 09:10 Welcome & Opening Remarks Marianne Thyrring (DMI) Diane Campbell (ECCC) Juhani Damski, Director- 09:10 – 09:30 Welcome from the Finnish Meteorological Institute General, FMI 09:30 – 09:45 Participant Introductions All - Roundtable 09:45 – 09:45 Adoption of Agenda Co-Chairs 09:45 – 10:30 Committee Reports Wolfgang Dierking (AWI) 09:45 – 10:00 Applied Science and Research Standing Committee Dean Flett (CIS) Phillip Reid (BOM) Alvaro Scardilli (SHNA) Data, Information and Customer Support Standing 10:00 – 10:15 Penny Wagner (NIS) Committee Chris Readinger (NIC) Mike Hicks (IIP) 10:15 – 10:30 Iceberg Standing Committee Keld Qvistgaard (DMI) 10:30 – 10:45 Health Break John Falkingham 10:45 – 10:50 Report of the Secretariat (Secretariat) Reports from Other Ice Working Groups 10:50 – 11:00 Written reports/presentations to be circulated before the meeting. Presenters will be asked to highlight top issues verbally to save time. Baltic Sea Ice Meeting Antti Kangas (FMI) European Ice Services Nick Hughes (NIS) North American Ice Service Kristen Serumgard (IIP) IAPB / IPAB Kevin Berberich (NIC) Expert Team on Sea Ice Vasily Smolyanitsky (AARI) 11:00 – 11:15 Arctic Regional Climate Centre – PARCOF-1 Report John -

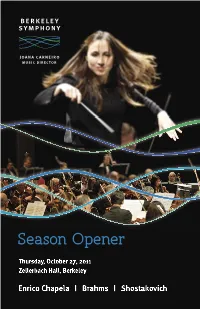

Berksymphfall11.Pdf

My life here Bette Ferguson, joined in 2006 My Life Here Is INDEPENDENT The people who live here are well-traveled and engaged with life. Their independent lifestyle is enhanced with our Continuing Care and contract options so they have all levels of healthcare under one roof. Find out why our established reputation as one of the very best not-for-profit communities is just one more reason people like Bette Ferguson know a good thing when they live it. To learn more, or for your personal visit, please call 510.891.8542. stpaulstowers-esc.org Making you feel right, at home. A fully accredited, non-denominational, not-for-profit community owned and operated by Episcopal Senior Communities. Lic. No. 011400627 COA #92 EPSP1616-01CJ 100111 CLIENT ESC / St. Paul’s Towers PUBLICATION Berkeley Symphony AD NAME Bette Ferguson REFERENCE NUMBER EPSP616-01cj_Bette_01_mech TYPE Full Page Color - Inside Front Cover TRIM SIZE 4.75” x 7.25” ISSUE 2011/12 Season MAT’LS DUE 9.01.11 DATE 08.22.11 VERSION 01 mech AGENCY MUD WORLDWIDE 415 332 3350 Berkeley Symphony 2011-12 Season 5 Message from the President 7 Board of Directors & Advisory Council 9 Message from the Music Director 11 Joana Carneiro 13 Berkeley Symphony 16 October 27 Orchestra 19 October 27 Program 21 October 27 Program Notes 31 October 27 Guest Artists 41 December 8 Program 43 December 8 Program Notes 53 December 8 Guest Conductor Jayce Ogren 55 December 8 Guest Artists 57 Meet the Orchestra 60 Music in the Schools 63 Under Construction 65 Contributed Support 72 Advertiser Index Season Sponsors: Kathleen G. -

AGENDA “Ice Information for Navigating the Sub-Polar Seas” MONDAY, SEPTEMBER 24 Plenary Sessions Will Be Held in “Brainstorm” 08:30 – 09:00 Registration

th 19 MEETING OF THE INTERNATIONAL ICE CHARTING WORKING GROUP September 24-28, 2018 – Helsinki, Finland AGENDA “Ice Information for Navigating the Sub-Polar Seas” MONDAY, SEPTEMBER 24 Plenary Sessions will be held in “Brainstorm” 08:30 – 09:00 Registration 09:00 – 09:45 Official Meeting Opening Co-Chairs 09:00 – 09:10 Welcome & Opening Remarks Marianne Thyrring (DMI) Tom Cuff (NOAA) Juhani Damski, Director- 09:10 – 09:30 Welcome from the Finnish Meteorological Institute General, FMI 09:30 – 09:35 Meeting Logistics Antti Kangas (FMI) 09:35 – 09:45 Participant Introductions All - Roundtable 09:45 – 09:45 Adoption of Agenda Co-Chairs 09:45 – 10:30 Committee Reports Wolfgang Dierking (AWI) 09:45 – 10:00 Applied Science and Research Standing Committee Dean Flett (CIS) Phillip Reid (BOM) Alvaro Scardilli (SHNA) Data, Information and Customer Support Standing 10:00 – 10:15 Penny Wagner (NIS) Committee Chris Readinger (NIC) Mike Hicks (IIP) 10:15 – 10:30 Iceberg Standing Committee Keld Qvistgaard (DMI) 10:30 – 10:45 Health Break John Falkingham 10:45 – 10:50 Report of the Secretariat (Secretariat) Reports from Other Ice Working Groups 10:50 – 11:00 Written reports/presentations to be circulated before the meeting. Presenters will be asked to highlight top issues verbally to save time. Baltic Sea Ice Meeting Jürgen Holfort (BSH) European Ice Services Nick Hughes (NIS) North American Ice Service Kristen Serumgard (IIP) IAPB / IPAB John Woods (NIC) Expert Team on Sea Ice Vasily Smolyanitsky (AARI) 11:00 – 11:15 Arctic Regional Climate -

Unidentified Aerial Phenomena - Eighty Years of Pilot Sightings

NARCAP TR-04 2001 D. F. Weinstein NARCAP TR-04 Date of Report: February 2001 Unidentified Aerial Phenomena - Eighty Years of Pilot Sightings A Catalog of Military, Airliner, and Private Pilots sightings from 1916 to 2000 Dominique F. Weinstein NARCAP International Technical Advisor France © Copyright 2001 Dominique Weinstein, February 2001 edition 1300+ cases NARCAP P.O. Box 140, Boulder Creek, California 95006-0880, USA www.narcap.org 1 NARCAP TR-04 2001 D. F. Weinstein Acknowledgements : I would like to thank Dr Richard F. Haines (NARCAP Chief Scientist), for his advises and his close- cooperation, Dr Peter Sturrock and Dr Jacques Vallée for their help and encouragements, Jean-Jacques Velasco (GEPAN-SEPRA), Gustavo Rodriguez (CEFAA-Chile) and Patrick Leprevost, Air France pilot, for his cooperation and expertise. and also : Jan L. Aldrich (Project 1947 / Sign Historical Group), Vicente-Juan Ballester Olmos (Fundacion Anomalia - Spain), Don Berliner (FUFOR - USA), Barry Greenwood (UFO Historical Revue - USA), Loren Gross (for the gift of the complete collection of his very interesting series : UFOs a history), Larry Hatch (*U* UFO Database - USA),(Richard Hall (FUFOR - USA), Don Ledger (Canada), Marco Orlandi (CISU – Italy), Joel Mesnard (LDLN - France), Edoardo Russo (CISU) and Ed Stewart. Abbreviations and Codes Table AB Air Base (US air force base outside U.S. territory) AF Air FORCE AFB Air Force Base (US Air Force Base in U.S. territory) ANG Air National Guard ARTCC Air Route Traffic Control Center ATIC Air Technical Intelligence -

Women Collectors and Cultural Philanthropy, C. 1850–1920 Tom Stammers

Women Collectors and Cultural Philanthropy, c. 1850–1920 Tom Stammers At the Barber Institute of Fine Arts, one of the finest university art m useums in the country, signs of its founding matriarch are few. As an anniversary publication makes clear, Lady Barber — née Martha Constance Hattie Onions (1869–1933) — was ‘no great intellectual force or major collector of fine art’.1 What she bequeathed to the University of Birmingham in 1932 was not a corpus of masterpieces but rather the funds to enable the con- struction of a building and a major purchasing spree. While subsequent male curators — like Thomas Bodkin — deserve the credit for the astonish- ing old masters assembled for the institute, Lady Barber’s own creative interests during her lifetime were centred on the home. At Culham Court, near Henley-on-Thames, where she lived with her property developer hus- band from 1893, Lady Barber introduced neo-Georgian decorations and dramatic alpine gardens. Furniture and especially textiles formed the most substantial part of her collecting, whether historic lace — sourced from the Midlands and Europe — or sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Flemish tapestries and cushion covers. These rich fabrics formed the backdrops in several of the twenty-five portraits that Lady Barber commissioned from the Belgian artist Nestor Cambier between 1914 and 1923. These range from highly theatrical full-length portraits in fancy dress, through to evocative sketches of the drawing room at Culham Court, depicting Lady Barber among her cherished possessions (Fig. 1). It appears Lady Barber was determined for the ensemble of portraits to be kept together after her death, since she arranged them into a privately printed book and lobbied (unsuccessfully) for their exhibition in London.