Young Massive Clusters: Their Population Properties, Formation and Evolution, and Their Relation to the Ancient Globular Clusters

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Density Profiles of Populous Star Clusters in the Magellanic Clouds

Density profiles of populous star clusters in the Magellanic Clouds Grigor Nikolov,1,2 Anastasos Dapergolas,3 Mary Kontizas,2 Valeri Golev,1 Maya Belcheva2 1 Department of Astronomy, Faculty of Physics, Sofia University, BG-1164 Sofia, Bulgaria 2 Department of Astrophysics, Astronomy & Mechanics, Faculty of Physics, University of Athens, GR-15783 Athens, Greece 3 IAA, National Observatory of Athens, GR-11810 Athens, Greece [email protected] (Conference poster) Abstract. The Large Magellanic Cloud (LMC) and the Small Magellanic Cloud (SMC) provide the unique opportunity to study young and populous star clusters. Some of them are elliptical in shape, or are members of a multiple systems, which are almost absent in the Milky Way. We have selected a sample of Magellanic Clouds’ star clusters, some of them candidates of a multiple system components, to investigate them by means of their number density profiles. This approach allows us to determine the radial distribution of the stars of different magnitude. Since the brighter stars have larger masses than the fainter stars, the profiles can be used to trace mass-segregation in the clusters. We have fitted a theoretical model by Elson, Fall & Freeman [1987] to determine the core radius and the concentration of the stars for each magnitude range. Key words: star clusters Профили на плътността на населени звездни купове в Магелановите облаци Григор Николов, Анастасос Даперголас, Мери Контизас, Валери Голев, Мая Белчева Големият и Малкият Магеланови облаци предлагат уникалната възможност за изуча- ване на млади богато населени звездни купове. Някои от тях имат елиптична форма или са членове на двойни системи, каквито се срещат много рядко в Млечния път. -

Luminosity - Wikipedia

12/2/2018 Luminosity - Wikipedia Luminosity In astronomy, luminosity is the total amount of energy emitted by a star, galaxy, or other astronomical object per unit time.[1] It is related to the brightness, which is the luminosity of an object in a given spectral region.[1] In SI units luminosity is measured in joules per second or watts. Values for luminosity are often given in the terms of the luminosity of the Sun, L⊙. Luminosity can also be given in terms of magnitude: the absolute bolometric magnitude (Mbol) of an object is a logarithmic measure of its total energy emission rate. Contents Measuring luminosity Stellar luminosity Image of galaxy NGC 4945 showing Radio luminosity the huge luminosity of the central few star clusters, suggesting there is an Magnitude AGN located in the center of the Luminosity formulae galaxy. Magnitude formulae See also References Further reading External links Measuring luminosity In astronomy, luminosity is the amount of electromagnetic energy a body radiates per unit of time.[2] When not qualified, the term "luminosity" means bolometric luminosity, which is measured either in the SI units, watts, or in terms of solar luminosities (L☉). A bolometer is the instrument used to measure radiant energy over a wide band by absorption and measurement of heating. A star also radiates neutrinos, which carry off some energy (about 2% in the case of our Sun), contributing to the star's total luminosity.[3] The IAU has defined a nominal solar luminosity of 3.828 × 102 6 W to promote publication of consistent and comparable values in units of https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Luminosity 1/9 12/2/2018 Luminosity - Wikipedia the solar luminosity.[4] While bolometers do exist, they cannot be used to measure even the apparent brightness of a star because they are insufficiently sensitive across the electromagnetic spectrum and because most wavelengths do not reach the surface of the Earth. -

THE MAGELLANIC CLOUDS NEWSLETTER an Electronic Publication Dedicated to the Magellanic Clouds, and Astrophysical Phenomena Therein

THE MAGELLANIC CLOUDS NEWSLETTER An electronic publication dedicated to the Magellanic Clouds, and astrophysical phenomena therein No. 135 — 1 June 2015 http://www.astro.keele.ac.uk/MCnews Editor: Jacco van Loon Editorial Dear Colleagues, It is my pleasure to present you the 135th issue of the Magellanic Clouds Newsletter. From magnetism and galactic structure and interaction, to variable, massive, (post-)AGB and exploding stars, and more on star cluster content – there’s something for everyone. Hope to see you at the IAU General Assembly in August, or in Baltimore in October! The next issue is planned to be distributed on the 1st of August. Editorially Yours, Jacco van Loon 1 Refereed Journal Papers Photometric identification of the periods of the first candidate extragalactic magnetic stars Ya¨el Naz´e1, Nolan R Walborn2, Nidia Morrell3, Gregg A Wade4 and MichaÃl K. Szyma´nski5 1University of LI`ege, Belgium 2STScI, USA 3Las Campanas Observatory, Chile 4Royal Military College, USA 5Warsaw University, Poland Galactic stars belonging to the Of?p category are all strongly magnetic objects exhibiting rotationally modulated spectral and photometric changes on timescales of weeks to years. Five candidate Of?p stars in the Magellanic Clouds have been discovered, notably in the context of ongoing surveys of their massive star populations. Here we describe an investigation of their photometric behaviour, revealing significant variability in all studied objects on timescales of one week to more than four years, including clearly periodic variations for three of them. Their spectral characteristics along with these photometric changes provide further support for the hypothesis that these are strongly magnetized O stars, analogous to the Of?p stars in the Galaxy. -

THE MAGELLANIC CLOUDS NEWSLETTER an Electronic Publication Dedicated to the Magellanic Clouds, and Astrophysical Phenomena Therein

THE MAGELLANIC CLOUDS NEWSLETTER An electronic publication dedicated to the Magellanic Clouds, and astrophysical phenomena therein No. 141 — 1 June 2016 http://www.astro.keele.ac.uk/MCnews Editor: Jacco van Loon Editorial Dear Colleagues, It is my pleasure to present you the 141st issue of the Magellanic Clouds Newsletter. There is a lot of interest in massive stars, star clusters, supernova remnants and binaries, but also several exciting new results about the large-scale structure of the Magellanic Clouds System. The next issue is planned to be distributed on the 1st of August 2016. Editorially Yours, Jacco van Loon 1 Refereed Journal Papers Non-radial pulsation in first overtone Cepheids of the Small Magellanic Cloud R. Smolec1 and M. Sniegowska´ 2 1Nicolaus Copernicus Astronomical Center, Warsaw, Poland 2Warsaw University Observatory, Warsaw, Poland We analyse photometry for 138 first overtone Cepheids from the Small Magellanic Cloud, in which Optical Gravitational Lensing Experiment team discovered additional variability with period shorter than first overtone period, and period ratios in the (0.60,0.65) range. In the Petersen diagram, these stars form three well-separated sequences. The additional variability cannot correspond to other radial mode. This form of pulsation is still puzzling. We find that amplitude of the additional variability is small, typically 2–4 per cent of the first overtone amplitude, which corresponds to 2–5 mmag. In some stars, we find simultaneously two close periodicities corresponding to two sequences in the Petersen diagram. The most important finding is the detection of power excess at half the frequency of the additional variability (at subharmonic) in 35 per cent of the analysed stars. -

IV. the Double Main Sequence of the Young Cluster NGC 1755

MNRAS 458, 4368–4382 (2016) doi:10.1093/mnras/stw608 Advance Access publication 2016 March 15 Multiple stellar populations in Magellanic Cloud clusters – IV. The double main sequence of the young cluster NGC 1755 A. P. Milone,1‹ A. F. Marino,1 F. D’Antona,2 L. R. Bedin,3 G. S. Da Costa,1 H. Jerjen1 and A. D. Mackey1 1Research School of Astronomy and Astrophysics, Australian National University, Canberra, ACT 2611, Australia 2Istituto Nazionale di Astrofisica – Osservatorio Astronomico di Roma, Via Frascati 33, I-00040 Monteporzio Catone, Roma, Italy 3Istituto Nazionale di Astrofisica – Osservatorio Astronomico di Padova, Vicolo dell’Osservatorio 5, Padova, I-35122, Italy Accepted 2016 March 10. Received 2016 March 8; in original form 2016 January 7 ABSTRACT Nearly all the star clusters with ages of ∼1–2 Gyr in both Magellanic Clouds exhibit an extended main-sequence turn-off (eMSTO) whose origin is under debate. The main scenarios suggest that the eMSTO could be either due to multiple generations of stars with different ages or to coeval stellar populations with different rotation rates. In this paper we use Hubble Space Telescope images to investigate the ∼80-Myr old cluster NGC 1755 in the LMC. We find that the MS is split with the blue and the red MS hosting about the 25 per cent and the 75 per cent of the total number of MS stars, respectively. Moreover, the MSTO of NGC 1755 is broadened in close analogy with what is observed in the ∼300-Myr-old NGC 1856 and in most intermediate-age Magellanic-Cloud clusters. -

A High Fraction of Be Stars in Young Massive Clusters: Evidence for A

Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 000, 1–6 (2015) Printed 27 August 2018 (MN LATEX style file v2.2) A high fraction of Be stars in young massive clusters: evidence for a large population of near-critically rotating stars N. Bastian1, I. Cabrera-Ziri1,2, F. Niederhofer3, S. de Mink4, C. Georgy5, D. Baade2, M. Correnti3, C. Usher1, M. Romaniello2 1Astrophysics Research Institute, Liverpool John Moores University, 146 Brownlow Hill, Liverpool L3 5RF, UK 2European Southern Observatory, Karl-Schwarzschild-Straße 2, D-85748 Garching bei M¨unchen, Germany 3Space Telescope Science Institute, 3700 San Martin Drive, Baltimore, MD 21218, USA 4Astronomical Institute Anton Pannekoek, University of Amsterdam, PO Box 94249, NL-1090GE Amsterdam, the Netherlands 5Geneva Observatory, University of Geneva, Maillettes 51, 1290, Sauverny, Switzerland Accepted. Received; in original form ABSTRACT Recent photometric analysis of the colour-magnitude diagrams (CMDs) of young mas- sive clusters (YMCs) have found evidence for splitting in the main sequence and ex- tended main sequence turn-offs, both of which have been suggested to be caused by stellar rotation. Comparison of the observed main sequence splitting with models has led various authors to suggest a rather extreme stellar rotation distribution, with a mi- nority (10 − 30%) of stars with low rotational velocities and the remainder (70 − 90%) of stars rotating near the critical rotation (i.e., near break-up). We test this hypothesis by searching for Be stars within two YMCs in the LMC (NGC 1850 and NGC 1856), which are thought to be critically rotating stars with decretion disks that are (par- tially) ionised by their host stars. -

Stellar Rotation the Missing Piece in Stellar Physics

Stellar rotation the missing piece in Stellar physics Collaborators: Richard de Grijs (MQ), Licai Deng (NAOC), Chengyuan Li (SYSU), Michael Albrow (UC), Petri Vaisanen (SAAO), Zara Randriamanakoto (SAAO) Weijia Sun (PKU) 07/14/2021 Why stellar rotation is important? Why stellar rotation is important? • Dynamo-driven magnetic activity • Stellar winds • Surface abundances • Chemical yields • Internal structure • External structure Why stellar rotation is important? • Dynamo-driven magnetic activity • Stellar winds • Surface abundances • Chemical yields • Internal structure • External structure Matt & Pudritz 2005 Why stellar rotation is important? • Dynamo-driven magnetic activity • Stellar winds • Surface abundances • Chemical yields • Internal structure • External structure Maeder & Meynet 2011 Why stellar rotation is important? • Dynamo-driven magnetic activity • Stellar winds • Surface abundances • Chemical yields • Internal structure • External structure Rivinius+2013 extended MSTO and split MS Found in Magellanic Clouds clusters rMS bMS NGC 1846 NGC 1856 1.5 Gyr 350 Myr Mackey et al. 2008 Milone et al. 2015 Not only in MC clusters Niederhofer et al. 2015 But also in Galactic OCs Pattern NGC 5822 0.9 Gyr Sun et al. 2019a Cordoni et al. 2018 What causes eMSTO and split MS? • Extended star formation history (eSFH) • Variability • A wide range of stellar rotations What causes eMSTO and split MS? Stellar rotation 300 0.0 250 Gravity darkening 0.5 1.0 200 (mag) 1.5 150 G M 2.0 100 2.5 50 pole-on (i = 0) 3.0 0.2 0.4 0.6 G G (mag) BP ° RP edge-on (i = 90) It’s mainly v sin i that affects the locus of a star in the CMD Georgy et al. -

Ngc Catalogue Ngc Catalogue

NGC CATALOGUE NGC CATALOGUE 1 NGC CATALOGUE Object # Common Name Type Constellation Magnitude RA Dec NGC 1 - Galaxy Pegasus 12.9 00:07:16 27:42:32 NGC 2 - Galaxy Pegasus 14.2 00:07:17 27:40:43 NGC 3 - Galaxy Pisces 13.3 00:07:17 08:18:05 NGC 4 - Galaxy Pisces 15.8 00:07:24 08:22:26 NGC 5 - Galaxy Andromeda 13.3 00:07:49 35:21:46 NGC 6 NGC 20 Galaxy Andromeda 13.1 00:09:33 33:18:32 NGC 7 - Galaxy Sculptor 13.9 00:08:21 -29:54:59 NGC 8 - Double Star Pegasus - 00:08:45 23:50:19 NGC 9 - Galaxy Pegasus 13.5 00:08:54 23:49:04 NGC 10 - Galaxy Sculptor 12.5 00:08:34 -33:51:28 NGC 11 - Galaxy Andromeda 13.7 00:08:42 37:26:53 NGC 12 - Galaxy Pisces 13.1 00:08:45 04:36:44 NGC 13 - Galaxy Andromeda 13.2 00:08:48 33:25:59 NGC 14 - Galaxy Pegasus 12.1 00:08:46 15:48:57 NGC 15 - Galaxy Pegasus 13.8 00:09:02 21:37:30 NGC 16 - Galaxy Pegasus 12.0 00:09:04 27:43:48 NGC 17 NGC 34 Galaxy Cetus 14.4 00:11:07 -12:06:28 NGC 18 - Double Star Pegasus - 00:09:23 27:43:56 NGC 19 - Galaxy Andromeda 13.3 00:10:41 32:58:58 NGC 20 See NGC 6 Galaxy Andromeda 13.1 00:09:33 33:18:32 NGC 21 NGC 29 Galaxy Andromeda 12.7 00:10:47 33:21:07 NGC 22 - Galaxy Pegasus 13.6 00:09:48 27:49:58 NGC 23 - Galaxy Pegasus 12.0 00:09:53 25:55:26 NGC 24 - Galaxy Sculptor 11.6 00:09:56 -24:57:52 NGC 25 - Galaxy Phoenix 13.0 00:09:59 -57:01:13 NGC 26 - Galaxy Pegasus 12.9 00:10:26 25:49:56 NGC 27 - Galaxy Andromeda 13.5 00:10:33 28:59:49 NGC 28 - Galaxy Phoenix 13.8 00:10:25 -56:59:20 NGC 29 See NGC 21 Galaxy Andromeda 12.7 00:10:47 33:21:07 NGC 30 - Double Star Pegasus - 00:10:51 21:58:39 -

The HST Survey of Magellanic-Cloud Clusters and of Their Stellar Populations

Formation, evolution, and survival of massive star clusters Proceedings IAU Symposium No. 316, 2015 c International Astronomical Union 2017 C. Charbonnel & A. Nota, eds. doi:10.1017/S1743921315009278 The HST survey of Magellanic-Cloud clusters and of their stellar populations A. P. Milone Research School of Astronomy & Astrophysics, Australian National University, Mt Stromlo Observatory, via Cotter Rd, Weston, ACT 2611, Australia. email: [email protected] Abstract. A large number of intermediate-age (∼1-2-Gyr old) globular clusters (GCs) in the Large and the Small Magellanic Cloud (MC) exhibit either bimodal or extended main-sequence (MS) turn off and dual red clump (RC). Moreover, recent papers have shown that the MS of the young clusters NGC 1844 and NGC 1856 is either broadened or split. These features of the color-magnitude diagram (CMD) are not consistent with a single isochrone and suggest that star clusters in MCs have experienced a prolonged star formation, in close analogy with Milky-Way GCs with multiple stellar populations. As an alternative, stellar rotation or interacting binaries can be responsible of the CMD morphology. In the following I will summarize the observational scenario and provide constraints on the nature of the complex CMD of young and intermediate- age MC clusters from our ongoing photometric survey with the Hubble Space Telescope (HST ). 1. Introduction It is now widely accepted that the CMD of nearly all the old Galactic GCs (GGCs) is made of multiple sequences that can be identified along the entire diagram, from the bottom of the MS up to the sub-giant branch (SGB), the red-giant branch (RGB) and even the horizontal branch and the asymptotic giant branch (e.g. -

Resolved Massive Cluster Formation at Low and High Redshift Nate Bastian (Liverpool JMU) Stellar Clusters

Resolved Massive Cluster Formation at Low and High Redshift Nate Bastian (Liverpool JMU) Stellar Clusters Type Age Mass Found where star- Open 0 - (3-10) Gyr 100 - 104 Mo formation is happening where star- Young Massive <100 Myr or > 104 Mo formation is Clusters (YMCs) 0 - (1-10) Gyr happening >10 Gyr or Globular > 104 Mo bulge/halo >6 Gyr Nuclear all ages > 105 Mo nucleus Stellar Clusters Type Age Mass Found where star- Open 0 - (3-10) Gyr 100 - 104 Mo formation is happening where star- Young Massive <100 Myr or > 104 Mo formation is Clusters (YMCs) 0 - (1-10) Gyr happening >10 Gyr or Globular > 104 Mo bulge/halo >6 Gyr Nuclear all ages > 105 Mo nucleus Stellar Clusters Type Age Mass Found where star- Open 0 - (3-10) Gyr 100 - 104 Mo formation is happening where star- Young Massive <100 Myr or > 104 Mo formation is Clusters (YMCs) 0 - (1-10) Gyr happening >10 Gyr or Globular > 104 Mo bulge/halo >6 Gyr Nuclear all ages > 105 Mo nucleus Stellar Clusters Type Age Mass Found where star- Open 0 - (3-10) Gyr 100 - 104 Mo formation is happening where star- Young Massive <100 Myr or > 104 Mo formation is Clusters (YMCs) 0 - (1-10) Gyr happening >10 Gyr or Globular > 104 Mo bulge/halo >6 Gyr see recent review by Neumeyer, Seth and Nuclear all ages > 105 Mo nucleus Boeker ARA&A Stellar Clusters Type Age Mass Found where star- Open 0 - (3-10) Gyr 100 - 104 Mo formation is happening where star- Young Massive <100 Myr or > 104 Mo formation is Clusters (YMCs) 0 - (1-10) Gyr happening >10 Gyr or Globular > 104 Mo bulge/halo >6 Gyr see recent review -

Florian Niederhofer1,2 Michael Hilker1 Nate Bastian3 Esteban Silva-Villa4,5

Florian Niederhofer1,2 Michael Hilker1 Nate Bastian3 Esteban Silva-Villa4,5 1- European Southern Observatory 2- Universitäts-Sternwarte München 3- John Moores University Liverpool 4- CRAQ 5- Universidad de Antioquia NGC 2100 Credit: ESO Searching for Age Spreads ! Color-magnitude diagrams of intermediate age (1-2 Gyr) massive clusters in the LMC show extended or double main sequence turn-offs (MSTO) NGC 1783, NGC 1806 and NGC 1846 (Mackey et al. 2008) ! If these features are related to an age spread of 200-500 Myr, young clusters (<1 Gyr) with similar properties should have age spreads of the same order, as well ! We searched for age spreads in a sample of eight young (< 1.1 Gyr) 4 massive (> 10 M") LMC clusters ! The data set consists of archival HST WFPC2 data from Brocato et al. 2001, Fischer et al. 1998 and the Hubble Legacy Archive RASPUTIN Workshop 13.-17. October 2014 Our Cluster Sample ! The selected clusters cover the age range from 20 Myr to ≈ 1 Gyr ! They follow the same mass-effective radius relation as the intermediate age clusters that show an extended MSTO ! Blue circles: Clusters analyzed in this study ! Blue dots surrounded by circles: Clusters already analyzed by Bastian & Silva-Villa 2013 ! Red triangles: Intermediate age (1-2 Gyr) clusters that show extended or double MS turn- offs (Goudfrooij 2009,11a) ! Black dots: Other LMC clusters RASPUTIN Workshop 13.-17. October 2014 CMDs of the Clusters NGC 2249 NGC 1831 NGC 2136 NGC 2157 NGC 1850 NGC 1847 Stars that are used for NGC 2004 NGC 2100 further analysis Red crosses: Stars that are removed as field stars Niederhofer et al. -

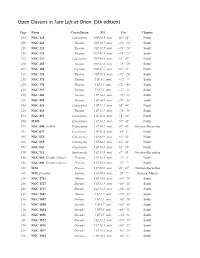

Open Clusters PAGING

Open Clusters in Turn Left at Orion (5th edition) Page Name Constellation RA Dec Chapter 193 NGC 129 Cassiopeia 0 H 29.8 min. 60° 14' North 210 NGC 220 Tucana 0 H 40.5 min. −73° 24' South 210 NGC 222 Tucana 0 H 40.7 min. −73° 23' South 210 NGC 231 Tucana 0 H 41.1 min. −73° 21' South 192 NGC 225 Cassiopeia 0 H 43.4 min. 61° 47' North 210 NGC 265 Tucana 0 H 47.2 min. −73° 29' South 202 NGC 188 Cepheus 0 H 47.5 min. 85° 15' North 210 NGC 330 Tucana 0 H 56.3 min. −72° 28' South 210 NGC 371 Tucana 1 H 3.4 min. −72° 4' South 210 NGC 376 Tucana 1 H 3.9 min. −72° 49' South 210 NGC 395 Tucana 1 H 5.1 min. −72° 0' South 210 NGC 460 Tucana 1 H 14.6 min. −73° 17' South 210 NGC 458 Tucana 1 H 14.9 min. −71° 33' South 193 NGC 436 Cassiopeia 1 H 15.5 min. 58° 49' North 210 NGC 465 Tucana 1 H 15.7 min. −73° 19' South 193 NGC 457 Cassiopeia 1 H 19.0 min. 58° 20' North 194 M103 Cassiopeia 1 H 33.2 min. 60° 42' North 179 NGC 604, in M33 Triangulum 1 H 34.5 min. 30° 47' October–December 195 NGC 637 Cassiopeia 1 H 41.8 min. 64° 2' North 195 NGC 654 Cassiopeia 1 H 43.9 min. 61° 54' North 195 NGC 659 Cassiopeia 1 H 44.2 min.