Diminished Masterpieces

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Quantitative Literacy: Why Numeracy Matters for Schools and Colleges, Held at the National Academy of Sciences in Washington, D.C., on December 1–2, 2001

NATIONAL COUNCIL ON EDUCATION AND THE DISCIPLINES The goal of the National Council on Education and the Disciplines (NCED) is to advance a vision that will unify and guide efforts to strengthen K-16 education in the United States. In pursuing this aim, NCED especially focuses on the continuity and quality of learning in the later years of high school and the early years of college. From its home at The Woodrow Wilson National Fellowship Foundation, NCED draws on the energy and expertise of scholars and educators in the disciplines to address the school-college continuum. At the heart of its work is a national reexamination of the core literacies—quantitative, scientific, historical, and communicative — that are essential to the coherent, forward-looking education all students deserve. Copyright © 2003 by The National Council on Education and the Disciplines All rights reserved. International Standard Book Number: 0-9709547-1-9 Printed in the United States of America. Foreword ROBERT ORRILL “Quantitative literacy, in my view, means knowing how to reason and how to think, and it is all but absent from our curricula today.” Gina Kolata (1997) Increasingly, numbers do our thinking for us. They tell us which medication to take, what policy to support, and why one course of action is better than another. These days any proposal put forward without numbers is a nonstarter. Theodore Porter does not exaggerate when he writes: “By now numbers surround us. No important aspect of life is beyond their reach” (Porter, 1997). Numbers, of course, have long been important in the management of life, but they have never been so ubiquitous as they are now. -

Princeton University Press Spring 2017 Catalog

A NEW YOrk TimES BEstsEllER The Rise and Fall of American Growth The U.S. Standard of Living since the Civil War ROBErt J. GORDON In the century after the Civil War, an economic revolution improved the American standard of living in ways previously unimaginable. Electric lighting, indoor plumbing, motor vehicles, air travel, and television transformed households and workplaces. But has that era of unprecedented growth come to an end? Weaving together a vivid narrative, historical anecdotes, and economic analysis, The Rise and Fall of American Growth provides an in-depth account. Gordon chal- lenges the view that economic growth will continue unabated, and The New York Times bestseller he demonstrates that the life-altering scale of innovations between 1870 and 1970 cannot be repeated. He contends that the nation’s about why America’s high- productivity growth will be further held back by the headwinds of growth era may be over rising inequality, stagnating education, an aging population, and the rising debt of college students and the federal government; and that we must find new solutions to overcome the challenges facing us. A critical voice in the debates over economic stagnation, The Rise and Robert J. Gordon is professor in social Fall of American Growth is at once a tribute to a century of radical sciences at Northwestern Univer- change and a harbinger of tougher times to come. sity. His books include Productivity Growth, Inflation, and Unemployment “A fantastic read.”—Bill Gates, GatesNotes and Macroeconomics. Gordon was included in the 2013 Bloomberg list of “A magisterial combination of deep technological history, vivid the nation’s most influential thinkers. -

Lulu's Daughters

LULU’S DAUGHTERS: PORTRAYING THE ANTI-HEROINE IN CONTEMPORARY OPERA, 1993-2013 by NICHOLAS DAVID STEVENS Dissertation Advisor: Dr. Susan McClary Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Music CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY August, 2017 CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES We hereby approve the thesis/dissertation of Nicholas David Stevens candidate for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy*. Dr. Susan McClary Committee Chair Dr. Daniel Goldmark Committee Member Dr. Francesca Brittan Committee Member Dr. Susanne Vees-Gulani Committee Member Dr. Sherry Lee Additional Member Faculty of Music, University of Toronto Date of Defense: April 28, 2017 *We also certify that written approval has been obtained for any proprietary material contained therein. TABLE OF CONTENTS Figures ii Examples iii Tables iv Acknowledgments v Abstract ix Chapter 1 Lulu’s Daughters: An Introduction 1 Part I: Remembering the Twentieth Century Chapter 2 Old, New, Borrowed, Blew: Powder Her Face, Polarity, and the Backward Glance 39 Chapter 3 My Heart Belongs to Daddy: Editing, Archetypes, and Anaïs Nin 103 Part II: American Dreams, Southern Scenes, and European (Re)visions Chapter 4 Trashy Traviata: Class, Media, and the American Prophecy of Anna Nicole 157 Chapter 5 Berg, Billie, and Blue Velvet: American Lulu and its Catastrophic Stage(s) 207 Conclusion The Marilyn Triptych and the Cracked Killing Jar: Ways Forward for Opera and 251 Scholarship Supporting Materials Appendix A Timeline of selected significant events, premieres, and publications, 1835-2017 261 Appendix B Louis Andriessen’s libretto for Anaïs Nin and its source materials: a comparison 267 Appendix C Olga Neuwirth’s cuts and edits to Berg’s Lulu in American Lulu 278 Bibliography 283 iv FIGURES 2.1. -

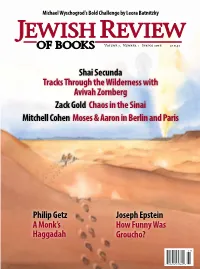

Michael Wyschogrod's Bold Challenge by Leora Batnitzky JEWISH REVIEW of BOOKS Volume 7, Number 1 Spring 2016 $10.45

Michael Wyschogrod's Bold Challenge by Leora Batnitzky JEWISH REVIEW OF BOOKS Volume 7, Number 1 Spring 2016 $10.45 Shai Secunda Tracks Through the Wilderness with Avivah Zornberg Zack Gold Chaos in the Sinai Mitchell Cohen Moses & Aaron in Berlin and Paris Philip Getz Joseph Epstein A Monk’s How Funny Was Haggadah Groucho? Editor Abraham Socher “MIRIAM’S SONG will NEW Senior Contributing Editor RELEASE inspire those who read it, Allan Arkush as it has inspired me.” Art Director W IRIAM S ONG Betsy Klarfeld NE “M ’ S will inspire those who read it, BENJAMIN NETANYAHU Managing Editor SE Amy Newman Smith RELEA as it has inspired me.” BENJAMIN NETANYAHU Editorial Assistant Kate Elinsky Editorial Board 1st Lieutenant Uriel Peretz, Robert Alter Shlomo Avineri Golani Brigade Special Leora Batnitzky Ruth Gavison Forces unit commander, Moshe Halbertal Jon D. Levenson dreamed of becoming the Anita Shapira Michael Walzer first Moroccan chief of staff J. H.H. Weiler Leon Wieseltier of the IDF. Ruth R. Wisse Steven J. Zipperstein On the day he was drafted, Miriam became a woman Publisher waiting for news of disaster. Eric Cohen In November 1998, Uriel Associate Publisher & was fatally wounded by an Director of Marketing explosive device planted Lori Dorr by Hezbollah terrorists. He was 22 years old. JRB Publication Committee Tragically, in March 2010 Miriam was forced to face another test. Her second son, Anonymous Martin J. Gross Major Eliraz Peretz, was killed in an exchange of fire in the 1st Lieutenant Uriel Peretz, Golani Brigade Special Gaza Strip. Forces unit commander, dreamed of becoming the Susan and Roger Hertog first Moroccan chief of staff of the IDF. -

AMS OPUS Campaign: Report to Donors (2011)

American Musicological Society, Inc. Report to Donors May 2011 Table of Contents 1 Introduction: Letter from Past Presidents of the American Musicological Society during the OPUS campaign 3 Letters from the National Endowment for the Humanties, the Gladys Krieble Delmas Foundation, and the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation 7 Letter from OPUS Campaign Co-chairs D. Kern Holoman and Anne Walters Robertson 9 Financial Statement 10 Society Awards, Grants, and Fellowships Supported by the OPUS Campaign 16 Books and Editions Subvented by the Society with OPUS Funds 23 List of Donors May 15, 2011 To the Members and Friends of the American Musicological Society: We the presidents of the American Musicological Society, along with the Boards of Directors who have served with us, are delighted to extend our thanks to each donor recognized in the following pages. The AMS OPUS campaign was launched in 2002, in anticipation of the Society’s seventy- fifth anniversary, with the goal of establishing a substantial endowment in support of travel and research; fellowships, prizes and awards; and publications. Thanks to your efforts we were able to raise $2,200,000 dollars, a stately sum indeed. We were aided considerably by a challenge grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities and by additional grants from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation and the Gladys Krieble Delmas Foundation. But it was the sustained labor and generosity of many constituents—the OPUS Committee, chaired so capably first by our own Jessie Ann Owens and then by D. Kern Holoman and Anne Walters Robertson; the AMS Chapters; our colleagues in private enterprise; those who participated in benefit concerts or other activities; friends of the Society; and of course the membership at large—that moved us constantly toward our goal and enabled the campaign to reach a successful conclusion at the close of 2009. -

Historymusicdepartment1 1

THE HARVARD UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC 1991 TO 2011 Compiled and Edited by Lesley Bannatyne 2015 John Knowles Paine Concert Hall. Photo by Shannon Cannavino. Cover photos by Kris Snibbe [Harvard News Office], HMFH Architects, Inc., Harvard College Libraries, Rose Lincoln [Harvard News Office] THE HARVARD UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC 1991 TO 2011 Compiled and Edited by Lesley Bannatyne Department of Music Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts 2015 Photographs in this volume were provided by the Department of Music unless otherwise noted. Articles are reprinted from the Department’s newsletters, Harvard Crimson and Harvard Gazette. © 2015 President and Fellows of Harvard University 2nd printing January 2017 All rights reserved. CONTENTS Preface vii Chapter One: The Chairs 1 Chapter Two: Undergraduate Studies 11 Chapter Three: Graduate Studies 23 Chapter Four: Musicology 33 Chapter Five: Ethnomusicology 51 Chapter Six: Theory 67 Chapter Seven: Composition 77 Chapter Eight: Performance 97 Chapter Nine: Conferences, Symposia, Colloquia, Lectures 111 Chapter Ten: Concert Highlights 119 Chapter Eleven: Eda Kuhn Loeb Music Library 127 Chapter Twelve: The Building 143 Appendices 151 Index 307 Music Department, 1992 Music Department picnic, late 1990s Appendices i. Music Department Faculty 151 ii. Biographical Sketches of Senior Professors, Lecturers & Preceptors 165 iii. Donors 175 iv. Teaching Fellows 179 v. Curriculum 183 vi. Fromm Commissions 207 vii. Recipients of the PhD degree 211 viii. Faculty Positions Held by Former Graduate Students 217 ix. Recipients of Department Awards and Fellowships 221 x Recipients of the AB degree and Honors Theses 227 xi. Visiting Committees 239 xii. Conferences, Colloquia, Symposia, Lectures 241 xiii. Concerts and Special Events 255 xiv. -

P. 1 CURRICULUM VITAE 1. Rose Rosengard Subotnik, Profess

Rose Rosengard Subotnik, Curriculum Vitae, through December 3, 2015: p. 1 CURRICULUM VITAE 1. Rose Rosengard Subotnik, Professor of Music Emerita /Visiting Professor of Music, Department of Music, Brown University. 2. WORK ADDRESS Box 1924 (Department of Music)/ Brown University /Providence, RI 02906 (401) 863-3234; [email protected] HOME ADDRESS 1 Meroke Court, Huntington Station, NY 11766 (631) 424-3927 cell: (401) 274-4264 3. EDUCATION B.A. with general honors in music, Wellesley College, 1963. M.A. in musicology, Columbia University, 1965. University of Vienna, 1965-66 (Fulbright Scholarship). Ph.D. in musicology, Columbia University, 1973. Dissertation Topic: "Art and Popularity in Lortzing's Operas: The Effects of Social Change on a National Operatic Genre." 4. PROFESSIONAL APPOINTMENTS University of Chicago, 1973-80. Assistant Professor of Music, Member, Committee on History of Culture. Boston University, Summer, 1980. Visiting Lecturer in the graduate musicology program. City University of New York Graduate Center, 1986-87. Visiting Associate Professor of Music. State University of New York at Stony Brook, Spring 1987. Visiting Lecturer in the graduate musicology program. Brown University, 1990-. Associate Professor of Music, 1990-93. Professor of Music, 1993-2008. Brandeis University, Spring Semester, Spring Semester, 1998. Visiting Professor of Music and Women's Studies. Brown University, Professor of Music Emerita, 2008-. Brown University, Fall, 2008: Visiting Professor of Music. Brown University, Spring, 2010: Adjunct Professor of Music. Rose Rosengard Subotnik, Curriculum Vitae, through December 3, 2015: p. 2 5. COMPLETED RESEARCH AND SCHOLARSHIP (FOR ARTICLES IN PRESS SEE ALSO BELOW, #6) “RESEARCH IN PROGRESS) a. Books: Developing Variations: Style and Ideology in Western Music (Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, 1991). -

AMS Newsletter February 2012

AMS NEWSLETTER THE AMERICAN MUSICOLOGICAL SOCIETY CONSTITUENT MEMBER OF THE AMERICAN COUNCIL OF LEARNED SOCIETIES VOLUME XLII, NUMBER 1 February 2012 ISSN 0402-012X AMS/SEM/SMT New Orleans 2012: “Do You 2011 Annual Meeting: Know What it Means to Miss New Orleans?” San Francisco AMS New Orleans 2012 New Orleans can be a performance: from jazz By all reports, the meeting of the AMS in 1–4 November funerals to Mardi Gras parades, brass bands “the city” was a huge success. 1,563 delegates www.ams-net.org/neworleans to zydeco to bounce, music is in the very air converged on San Francisco from 10 to 13 of the city. As a port city with a multicultural November for the annual event, greeted by Apparently many of you do know what it heritage, New Orleans is a perfect place to fabulous weather, a friendly youthful vibe, means to miss New Orleans: I’ve heard that, have a joint meeting with our colleagues in the and a range of world-class culinary and cul- after the 1987 meeting, some began to question Society for Music Theory and the Society for tural opportunities to choose from. We were why the Annual Meeting needed to be held in Ethnomusicology. You should be aware that grateful that threats of labor unrest at the ho- a different city each year. In any case, those Halloween is a major holiday for some New tel did not materialize, allowing us to enjoy of you who have been awaiting a return to Orleanians, so, if you’re planning to come a a luxurious facility replete with a grand “city the Crescent City and those who missed that day or more ahead, book early! of lights” lobby familiar from the Mel Brooks meeting now have your chance! (By the way, November is a terrific time to visit southern parody High Anxiety. -

0101. Gustav Kobbé. Opera Singers, a Pictorial Souvenir, First Edition

0101. Gustav Kobbé. Opera Singers, A Pictorial Souvenir, First Edition. New York, Russell, 1901. c.80pp. Handsome Octavo Edition features extensive Biographical Chapters, w.Numerous (many full page) Lassù in cielo, 2s. 12” EL dark green Cetra BB 25202, only form of issue, 1 July, 1947. M-A, a gleaming copy. MB 8 Photos of Nordica, Calvé, Eames, Melba, Sembrich, Schumann-Heink, Albert Saléza, Zélie de Lussan, Johanna Gadski, Lucienne Bréval, Pol Plançon, Milka Terninia, Susan Strong, Antonio Scotti, Ernst van Dyck, Suzanne Adams, David Bispham, Fritzi Scheff, Maurice Grau, Jean & Edouard de Reszké and many others. MB 75 0102. Gustav Kobbé. Opera Singers, A Pictorial Souvenir, Second Edition. Boston, Ditson, 1904. c.100pp. Handsome Octavo Edition features extensive Biographical Chapters, w.Numerous (many full page) Photos of Nordica, Calvé, Eames, Melba, Schumann-Heink, Sembrich, Milka Terninia, Caruso, Jean & Edouard de Reszké, Albert Saléza, Johanna Gadski, Zélie de Lussan, Lucienne Bréval, Pol Plançon, Antonio Scotti, Ernst van Dyck, Suzanne Adams, Susan Strong, Fritzi Scheff, David Bispham, and many others. MB 75 0103. Gustav Kobbé. Opera Singers, A Pictorial Souvenir, Third Edition. Boston, Ditson, 1906. c.100pp. Handsome Octavo Edition features extensive Biographical Chapters, w.Numerous (many full page) Photos of Caruso, Calvé, Eames, Melba, Nordica, Schumann-Heink, Sembrich, Terninia, Jean & Edouard de Reszké, Gadski, Strong, Adams, Farrar, Bréval, van Dyck, Plançon, Bispham, Scotti, Homer, Lina Cavalieri, Ackté, Morena, Fremstad, Rappold, Kirkby-Lunn, Maurel, Alvarez, Campanari, Journet, Dippel, Saléza, Burgstaller, Ernst Krauss, Trentini, de Cisneros, Giannina Russ, Mr & Mrs Charles Gilibert, Alessandro Bonci, Vittorio Arimondi, Charles Dalmorès, Florencio Constantino, Francesco Tamagno, Alice Nielsen, Gertrude Rennyson, Francis Maclennan, Maurice Grau, and many others. -

Introduction 1

Notes Introduction 1. Aleksandra Wolska, “Rabbits, Machines, and the Ontology of Performance,” Theatre Journal 57, no. 1 (2005): 85, 88. 2. Ibid., 91. 3. See Kathleen Ashley, “Sponsorship, Reflexivity and Resistance: Cultural Readings of the York Cycle Plays,” in The Performance of Middle English Cultures: Essays on Chaucer and Drama in Honor of Martin Stevens, eds. James J. Paxson, Lawrence M. Clopper, and Sylvia Tomasch, 9–24 (Cambridge: Boydell and Brewer, 1998); Sarah Beckwith, Signifying God: Social Relation and Symbolic Act in the York Corpus Christi Plays (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001); and Claire Sponsler, Drama and Resistance: Bodies, Goods, and Theatricality in Late Medieval England (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1997). 4. There are certainly exceptions. Two recent publications that address this gap are: Theodore K. Lerud, Memory, Images, and the English Corpus Christi Drama (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008) and various essays in Visualizing Medieval Performance: Perspectives, Histories, Contexts, ed. Elina Gertsman (Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2008). 5. David Morgan, Visual Piety: A History and Theory of Popular Religious Images (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998), 1. 6. The narrator in Piers Plowman recalls: “The ladies danced until the day dawned, / When the men rang bells to the resurrection—right then I woke, / And I called to Kytt my wife and Calote my daugh- ter: / “Rise and go do honor to God’s resurrection, / And creep to the cross on knees, and kiss it as if it were a jewel!” William Langland, The Vision of Piers Plowman, ed. A. V. C. Schmidt, 2nd ed. (London: J. M. Dent, 1995), 325.