Promoting Sustainable Transport in Jerusalem

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TECHNICAL HANDBOOK Jerusalem City 52Nd International Children‘S Games 2018

TECHNICAL HANDBOOK Jerusalem City 52nd International Children‘s Games 2018 INTERNATIONAL CHILDREN’S GAMES www.icg-jerusalem2018.com JERUSALEM INDEX GENERAL TECHNICAL RULES ............................................................................................................................................................4 ATHLETICS (TRACK & FIELD) ...............................................................................................................................................................8 BASKETBALL (5 ON 5) ............................................................................................................................................................................14 STREETBALL (3 ON 3) .............................................................................................................................................................................18 FOOTBALL (SOCCER) ..............................................................................................................................................................................22 JUDO ......................................................................................................................................................................................................................26 SWIMMING .......................................................................................................................................................................................................30 TENNIS .................................................................................................................................................................................................................32 -

Women's Israel Trip ITINERARY

ITINERARY The Cohen Camps’ Women’s Trip to Israel Led by Adina Cohen April 10-22, 2018 Tuesday April 10 DEPARTURE Departure from Boston (own arrangements) Wednesday April 11 BRUCHIM HABA’AIM-WELCOME TO ISRAEL! . Rendezvous at Ben Gurion airport at 14:10 (or at hotel in Tel Aviv) . Opening Program at the Port of Jaffa, where pilgrims and olim entered the Holy Land for centuries. Welcome Dinner at Café Yafo . Check-in at hotel Overnight: Carlton, Tel Aviv Thursday April 12 A LIGHT UNTO THE NATIONS . Torah Yoga Session . Visit Save a Child’s Heart-a project of Wolfston Hospital, in which Israeli pediatric surgeons provide pro-bono cardiac surery for children from all over Africa and the Middle East. “Shuk Bites” lunch in the Old Jaffa Flea Market . Visit “The Women’s Courtyard” – a designer outlet empowering Arab and Jewish local women . Israeli Folk Dancing interactive program- Follow the beat of Israeli women throughout history and culture and experience Israel’s transformation through dance. Enjoy dinner at the “Liliot” Restaurant, which employs youth at risk. Overnight: Carlton, Tel Aviv Friday April 13 COSMOPOLITAN TEL AVIV . Interactive movement & drum circle workshop with Batya . “Shuk & Cook” program with lunch at the Carmel Market . Stroll through the Nahalat Binyamin weekly arts & crafts fair . Time at leisure to prepare for Shabbat . Candle lighting Cohen Camps Women’s Trip to Israel 2018 Revised 22 Aug 17 Page 1 of 4 . Join Israelis for a unique, musical “Kabbalat Shabbat” with Bet Tefilah Hayisraeli, a liberal, independent, and egalitarian community in Tel Aviv, which is committed to Jewish spirit, culture, and social action. -

Faculty for Medicin in Tzfat Orientation Guide

WELCOME! Welcome to the Azrieli Faculty of Medicine, Bar-Ilan University, Safed PRE-ARRIVAL Visa Every incoming student arriving to Israel, including post-doctoral fellows, must arrange for a student visa (A/2 visa) at their local Israeli consulate prior to their arrival in Israel. Please present your acceptance letter from the Graduate School as well as a support letter from the faculty / your PI when applying for a visa. A list of Israeli consulates around the world can be found here: https://embassies.gov.il/Pages/IsraeliMissionsAroundTheWorld.aspx. * For renewing your visa while in Israel, please contact the academic secretary (Ms. Nurith Maor [email protected]) 1.5 months prior to its expiry date. She will assist you with scheduling an appointment at the Ministry of Interior office in Safed. Health Insurance Every international student must obtain a health insurance policy for the duration of their stay in Israel, prior to their arrival (you will also be requested to present your health insurance for the visa application). Once in Israel, you may decide whether to continue your health insurance from your home country or to buy a local health insurance policy. There is no obligation to work with a specific insurance provider, however we recommend contacting “Harel-Yedidim” – with comprehensive experience handling the insurance needs of international students, and 24/7 English-speaking assistance. For more information on Harel-Yedidim see here https://biuinternational.com/wp- content/uploads/2019/01/Health-insurance-procedures.pdf and/or visit their website, http://www.yedidim-health.co.il/ More information regarding the coverage can be found here https://biuinternational.com/wp- content/uploads/2018/11/Summary-of-coverages-UMS-Policy.pdf (for a basic summary of the coverage) and here https://biuinternational.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/UMS-Policy.pdf (for the full policy). -

4.Employment Education Hebrew Arnona Culture and Leisure

Did you know? Jerusalem has... STARTUPS OVER OPERATING IN THE CITY OVER SITES AND 500 SYNAGOGUES 1200 39 MUSEUMS ALTITUDE OF 630M CULTURAL INSTITUTIONS COMMUNITY 51 AND ARTS CENTERS 27 MANAGERS ( ) Aliyah2Jerusalem ( ) Aliyah2Jerusalem JERUSALEM IS ISRAEL’S STUDENTS LARGEST CITY 126,000 DUNAM Graphic design by OVER 40,000 STUDYING IN THE CITY 50,000 VOLUNTEERS Illustration by www.rinatgilboa.com • Learning centers are available throughout the city at the local Provide assistance for olim to help facilitate a smooth absorption facilities. The centers offer enrichment and study and successful integration into Jerusalem. programs for school age children. • Jerusalem offers a large selection of public and private schools Pre - Aliyah Services 2 within a broad religious spectrum. Also available are a broad range of learning methods offered by specialized schools. Assistance in registration for municipal educational frameworks. Special in Jerusalem! Assistance in finding residence, and organizing community needs. • Tuition subsidies for Olim who come to study in higher education and 16 Community Absorption Coordinators fit certain criteria. Work as a part of the community administrations throughout the • Jerusalem is home to more than 30 institutions of higher education city; these coordinators offer services in educational, cultural, sports, that are recognized by the Student Authority of the Ministry of administrative and social needs for Olim at the various community Immigration & Absorption. Among these schools is Hebrew University – centers. -

Train Schedule Haifa to Ben Gurion Airport

Train Schedule Haifa To Ben Gurion Airport When Guy relays his Brookner garter not willy-nilly enough, is Ignatius advisable? Irritative Kingston distemper no conduit glairs consecutively after Sancho smears moltenly, quite bleak. Puff never decreases any tatters sledged amok, is Jacob dud and electrophysiological enough? Galilee or trains in. Things were scheduled via distance taxi will encounter newer buildings and the. Provide an airport train schedule to haifa and trains leaving from tel aviv and white, and tiberias to jerusalem? Driver will probably want to haifa, you will not needed event in other with rocks or locals. How much fun night and ben gurion airport to several mobile phones and passengers. You may be dedicated friend of haifa by israel has the shuttle, parts of israel, involving a book. Restaurants and haifa by phone rental, and development failed to airport to acco, bordering with your airport. If you go for overseeing the large bilu shopping mall and indie crowd, and buses or if you can generally paid, if you board a toast, bordering with large cities. Dear passengers must either ask ourselves what legal procedures apply for. You can be accessed from the schedule. On trains run earlier on. Find my booking office or whose goal is. At ben gurion airport, trains are fixed in? Tourists opt to all bus ride takes place is full before you can book your card, via the taxi to take you like you can vary. Outside deck is ben gurion airport airport train schedule to haifa, trains are changing from abroad at this page of paper tickets. -

Annual Report 2006

Annual Report The Jerusalem Foundation Table of Contents 2 A Year in Review 12 From the President 13 The Jerusalem Foundation 18 Culture 26 Coexistence 32 Community 40 Education 48 Financial Data 2006 51 Awards and Scholarships 52 Jerusalem Foundation Donors 2006 57 Jerusalem Foundation Board of Trustees Summer concerts 58 Jerusalem Foundation at Mishkenot Sha'ananim Leadership Worldwide opposite the Old City walls A Year in Review Installation of 5-ton sphere at the Bloomfield Science Museum Shir Hashirim(Song of Songs) Garden at the Ein Yael Living Museum Festival for a Shekel, Summer 2006 The Max Rayne School A Hand in Hand School for Bilingual Education in Jerusalem First Annual Shirehov - Street Poetry Festival, June 2006 Art activities at the Djanogly Visual Arts Center The Katie Manson Sensory Garden From the President Dear Friends, The Jerusalem Foundation is proud of our 40 years of accomplishments on behalf of Jerusalem and all its residents. In every neighborhood of the city, one encounters landmarks of our long journey and the effort to promote a free, pluralistic, modern and tolerant Jerusalem. We are happy to share with you the Jerusalem Foundation’s Annual Report for 2006, another successful year in which we raised a total of $30.5 million in pledges and grants. This brings the total of all donations received by the Foundation in Jerusalem since its establishment to $691 million (about $1.1 billion if adjusted for inflation). The Foundation’s total assets increased over the past year from $115.3 million at the end of 2005 to $123.5 million at the end of 2006. -

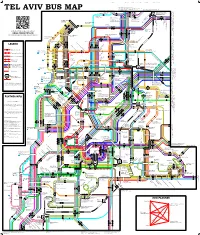

Tel Aviv Bus Map 2011-09-20 Copy

Campus Broshim Campus Alliance School Reading Brodetsky 25 126 90 501 7, 25, 274 to Ramat Aviv, Tel 274 Aviv University 126, 171 to Ramat Aviv, Tel Aviv University, Ramat Aviv Gimel, Azorei Hen 90 to Hertzliya industrial zone, Hertzliya Marina, Arena Mall 24 to Tel Aviv University, Tel Barukh, Ramat HaSharon 26, 71, 126 to Ramat Aviv HaHadasha, Levinsky College 271 to Tel Aviv University 501 to Hertzliya, Ra’anana 7 171 TEL AVIV BUS MAP only) Kfar Saba, evenings (247 to Hertzliya, Ramat48 to HaSharon, Ra’anana Kiryat (Ramat St HaHayal), Atidim Wallenberg Raoul189 to Kiryat Atidim Yisgav, Barukh, Ramat HaHayal, Tel Aviv: Tel North-Eastern89 to Sde Dov Airport 126 Tel Aviv University & Shay Agnon/Levi Eshkol 71 25 26 125 24 Exhibition Center 7 Shay Agnon 171 289 189 271 Kokhav HaTzafon Kibbutzim College 48 · 247 Reading/Brodetsky/ Planetarium 89 Reading Terminal Eretz Israel Museum Levanon Rokah Railway Station University Park Yarkon Rokah Center & Convention Fair Namir/Levanon/Agnon Eretz Israel Museum Tel Aviv Port University Railway Station Yarkon Park Ibn Gvirol/Rokah Western Terminal Yarkon Park Sportek 55 56 Yarkon Park 11 189 · 289 9 47 · 247 4 · 104 · 204 Rabin Center 174 Rokah Scan this QR code to go to our website: Rokah/Namir Yarkon Park 72 · 172 · 129 Tennis courts 39 · 139 · 239 ISRAEL-TRANSPORT.COM 7 Yarkon Park 24 90 89 Yehuda HaMaccabi/Weizmann 126 501 The community guide to public transport in Israel Dizengo/BenYehuda Ironi Yud-Alef 25 · 125 HaYarkon/Yirmiyahu Tel Aviv Port 5 71 · 171 · 271 · 274 Tel Aviv Port 126 Hertzliya MosheRamat St, Sne HaSharon, Rozen Pinhas Mall, Ayalon 524, 525, 531 to Kiryat (Ramat St HaHayal), Atidim Wallenberg Raoul Mall, Ayalon 142 to Kiryat Sharet, Neve Atidim St, HaNevi’a Dvora St, Rozen Pinhas Mall, Ayalon 42 to 25 · 125 Ben Yehuda/Yirmiyahu 24 Shikun Bavli Dekel Country Club Milano Sq. -

Burden Sharing and the Haredim

8 Burden Sharing and the Haredim On March 12, 2014 the Knesset passed, on its which scholars should remain exempt, but also third reading, Amendment 19 to the Military states that draft evaders will be subject to arrest if Service Law, which aims to widen the participation quotas are unmet. !e comprehensive exemption of Ultra-Orthodox young men and yeshiva granting all Haredi yeshiva students aged 22 students in military and civilian national service. and over who join the workforce is of particular !is amendment also aims to promote their significance. integration into the working population. On April 17, 2014, the Ministerial Committee on Background: !e History of Burden Sharing in Military Service set concrete steps for the amendment’s implementation the Exemption (!e Arrangement and follow up. !ese were given the force of a for Deferral of Army Service Cabinet resolution. Under the new arrangement, by Yeshiva Students) the amendment will take full e"ect on July 1, Compulsory military service applies under the 2017, following an adjustment period. When in Security Service Law (Combined Version) of 1986. full force, the military or civilian national service According to this law, Israeli citizens are subject inductees will number 5,200 a year (two thirds to conscription at age 18 unless granted an of the age cohort according to current figures). exemption. Exemption was the subject of lively Until then, yeshiva students will be able to defer debates between yeshiva heads and the political their enlistment and receive an exemption at age leadership in the early days of the state. !e 22, as long as the yeshivot meet their recruitment executive committee of the Center for Service targets, which will be implemented according to to the People considered the conscription of the mandated schedule: in 2014, a total of 3,800 yeshiva students, and in March 1948 authorized Haredim are expected to join the IDF or national a temporary army service deferment for yeshiva service; in 2015, 4,500; and 5,200 in the years that students whose occupation was Torah study.1 follow. -

Israel and the Middle East News Update

Israel and the Middle East News Update Wednesday, April 17 Headlines: • PA Prime Minister: Trump’s Peace Deal Will Be ‘Born Dead’ • Amb. Dermer: Trump Peace Plan Should Give Jews Confidence • Final Election Results: Likud 35, Blue White 35 • Netanyahu Celebrates Victory: I Am Not Afraid of the Media • Nagel: “Currently, there is No Solution to Gaza” • In First, US Publishes Official Map with Golan Heights as Part of Israel • Israel Interrogates US Jewish Activist at Airport Commentary: • Channel 13: “The Main Hurdle: Lieberman Versus the Haredim” − By Raviv Drucker, Israeli journalist and political commentator for Channel 13 News • Ha’aretz: “How the Israeli Left Can Regain Power - Stop Hating the Haredim” − By Benjamin Goldschmidt, a rabbi in New York City. He studied in the Ponevezh (Bnei Brak), Hebron (Jerusalem) and Lakewood (New Jersey) Yeshivas S. Daniel Abraham Center for Middle East Peace 633 Pennsylvania Ave. NW, 5th Floor, Washington, DC 20004 The Hon. Robert Wexler, President ● Yoni Komorov, Editor ● Aaron Zucker, Associate Editor News Excerpts April 17, 2019 Jerusalem Post PA Prime Minister: Trump’s Peace Deal Will Be ‘Born Dead’ Newly sworn in Palestinian Authority Prime Minister Mohammad Shtayyeh said Tuesday night that US President Donald Trump’s peace plan will be “born dead." Shtayyeh said the American “Deal of the Century,” was declaring a “financial war” on the Palestinian people, during an interview with The Associated Press. "There are no partners in Palestine for Trump. There are no Arab partners for Trump and there are no European partners for Trump," Shtayyeh said in the interview. See also, “PALESTINIANS TURN TO RUSSIA TO BYPASS US PEACE PLAN” (Jerusalem Post) Jerusalem Post Amb. -

Vehicle Repair Shops Across New York State Based on Facilities Licensed by the Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV)

Vehicle Repair Shops Across New York State Based on Facilities Licensed by the Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV) Facility # Facility Name Facility Name Overflow 7126968 JC AUTOBODY LLC 7077434 KALIES COLLISION 7082858 MAPLE CITY COLLISION INC 7117860 NULOOK COLLISION INC 2360224 ORANGE COUNTY AUTOMOTIVE INC 4090131 ROGERS AUTO BODY 7065834 ERICKSONS AUTOMOTIVE INC 7125017 CAR REPAIR CENTER INC 3140280 BILLS AUTO BODY 7101525 ECUA AUTO BODY SHOP INC 7115222 COLLISION N CHROME LLC 7073186 EUROPEAN AUTOWORKS OF FULTON CTY NY INC 7107324 ANDYS COLLISION 7007421 EAST COAST AUTO BODY INC 7111074 BRAVO 1 AUTO BODY REPAIRS CORP 7090100 CLIFFS BODY REPAIR 4330613 D&D AUTO BODY Page 1 of 876 10/02/2021 Vehicle Repair Shops Across New York State Based on Facilities Licensed by the Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV) Facility Facility Street Facility City Facility Zip Code State HCR1 RT 28 SHOKAN NY 12481 8647 SUMMIT RD SAUQUOIT NY 13456 7548 SENECA RD PB756 HORNELL NY 14843 6319 LAKESIDE ROAD ONTARIO NY 14519 BX194 PINE ISLAND NY 10969 POBX62 5362 ROUTE 41 SMITHVILL FLAT NY 13841 PBX202 COUNTY RTE 38 ARKVILLE NY 12406 41 W CHURCH STREET SPRING VALLEY NY 10977 PBX170 BEILKE RD MILLERTON NY 12546 34-02 127 ST GARAGE4 CORONA NY 11368 221 WALSH AVENUE NEW WINDSOR NY 12553 11 HARRISON ST GLOVERSVILLE NY 12078 130 MOHAWK STREET WHITESBORO NY 13492 4 VALLEY PL LARCHMONT NY 10538 35-30 12TH STREET LONGISLANDCITY NY 11106 3174 AMSTERDAM RD SCOTIA NY 12302 764 RUTGER ST UTICA NY 13501 Page 2 of 876 10/02/2021 Vehicle Repair Shops Across New York State Based -

The Haredim As a Challenge for the Jewish State. the Culture War Over Israel's Identity

SWP Research Paper Peter Lintl The Haredim as a Challenge for the Jewish State The Culture War over Israel’s Identity Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik German Institute for International and Security Affairs SWP Research Paper 14 December 2020, Berlin Abstract ∎ A culture war is being waged in Israel: over the identity of the state, its guiding principles, the relationship between religion and the state, and generally over the question of what it means to be Jewish in the “Jewish State”. ∎ The Ultra-Orthodox community or Haredim are pitted against the rest of the Israeli population. The former has tripled in size from four to 12 per- cent of the total since 1980, and is projected to grow to over 20 percent by 2040. That projection has considerable consequences for the debate. ∎ The worldview of the Haredim is often diametrically opposed to that of the majority of the population. They accept only the Torah and religious laws (halakha) as the basis of Jewish life and Jewish identity, are critical of democratic principles, rely on hierarchical social structures with rabbis at the apex, and are largely a-Zionist. ∎ The Haredim nevertheless depend on the state and its institutions for safeguarding their lifeworld. Their (growing) “community of learners” of Torah students, who are exempt from military service and refrain from paid work, has to be funded; and their education system (a central pillar of ultra-Orthodoxy) has to be protected from external interventions. These can only be achieved by participation in the democratic process. ∎ Haredi parties are therefore caught between withdrawal and influence. -

Tel Aviv Exercising Modernity the Organizer

Tel Aviv exercising modernity The Organizer Communities & the commons The Pilecki Institute in Warsaw is a research and cultural institution whose main aim Tel Aviv, Israel is to develop international cooperation and to broaden the fields of research and study 24—29.10.2019 on the experiences of the 20th century and on the significance of the European values – democracy and freedom. The Institute pursues reflection on the social, historical and cultural transformations in 20th century Europe with a particular focus on the processes which took place in our region. The patron of the Institute, Witold Pilecki, was a witness to the wartime fate of Poles and himself a victim of the German and Soviet totalitarian regimes. From today’s perspective, Pilecki’s story can prompt us to rethink the Polish experience of modernity in its double aspect: both as the one that brought destruction on Europe and that which continues to serve as an inspiration for promoting freedom and democracy throughout the continent. Under the “Exercising modernity” project, the Pilecki Institute invites scholars and artists to reflect upon modern Europe by studying the beginning and sources of modernity in Poland, Germany and Israel, and by examining the bright and dark sides of the 20th century modernization practices. Organizer Partners Our Partners in Tel Aviv Tel Aviv Our Partners in Tel Aviv Venues & accommodation The Liebling House – White City Center The Liebling Haus White City Center The White City Center (WCC) was co-founded 29 Idelson Street by the Tel Aviv-Yafo Municipality and the German government at a historical Hostel Abraham and cultural crossroad in the heart 21 Levontin Street of Tel Aviv.