New Urb Banism in N New Delhi I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Case Study Vikas Marg, New Delhi Laxmi Nagar Chungi to Karkari Mor

Equitable Road Space : Case study Vikas Marg, New Delhi Laxmi Nagar Chungi to Karkari Mor PWD, Govt. of NCT of Delhi Methodology Adopted STAGE 1 : Understand Equitable Road Space and Design STAGE 2 : Study of different Guidelines. STAGE 3 : Identification of Case Study Location and Data Collection STAGE 4 : Data Analysis STAGE 5 : Design Considerations Need for Equitable Road Space Benefits of Equitable Design Increase in comfort of pedestrians Comfortable last mile connectivity from MRTS Stations – therefore increased ridership of Buses and Metro. Reduced dependency on the car, if shorter trips can be made comfortably by foot. Prioritization of public transport and non- motorized private modes in street design. Reduced car use leading to reduced congestion and pollution. More equity in the provision of comfortable public spaces and amenities to all sections Source: Street Design Guidelines © UTTIPEC, DDA 2009 of society. Guidelines of UTTIPEC for Equitable Road Space GOALS FOR “INTEGRATED” STREETS FOR DELHI: GOAL 1: • MOBILITY AND ACCCESSIBILITY – Maximum number of people should be able to move fast, safely and conveniently through the city. GOAL 2: • SAFETY AND COMFORT – Make streets safe clean and walkable, create climate sensitive design. GOAL 3: • ECOLOGY – Reduce impact on the natural environment; and Reduce pressure on built infrastructure. Mobility Goals: To ensure preferable public transport use: 1. To Retrofit Streets for equal or higher priority for Public Transit and Pedestrians. 2. Provide transit-oriented mixed land use patterns and redensify city within 10 minutes walk of MRTS stops. 3. Provide dedicated lanes for HOVs (high occupancy vehicles) and carpool during peak hours. Safety, Comfort Goals: 4. -

NDMC Ward No. 001 S

NDMC Ward No. 001 S. No. Ward Name of Name of Name of Enumeratio Extent of the Population Enumeration Total SC % of SC Name & town/Census District & Tahsil & n Block No. Block Population Population Population Code Town/ Village Code Code 0001 NDMC 7003 New Delhi 05 Connaught 0021(1) Devi Prasad Sadan 1-64, NDMC Flats 4 Place 001 Type-6, Asha Deep Apartment 9 Hailey 1 Road 44 Flats 656 487 74.24 0001 NDMC 7003 New Delhi 05 Connaught 0029 Sangli Mess Cluster (Slum) 2 Place 001 351 174 49.57 0001 NDMC 7003 New Delhi 05 Connaught 0031(2) Feroz Shah Road, Canning Lane Kerala 3 Place 001 School 593 212 35.75 0001 NDMC 7003 New Delhi 05 Connaught 0032(1) Princess Park Residential Area Copper 4 Place 001 Nicus Marg to Tilak Marg, 100 Houses 276 154 55.8 0001 NDMC 7003 New Delhi 05 Connaught 0032(2) Princess Park Residential Area Copper 5 Place 001 Nicus Marg to Tilak Marg, 105 Houses 312 142 45.51 0001 NDMC 7003 New Delhi 05 Connaught 0036(1) NSCI Club Cluster-171 Houses 6 Place 001 521 226 43.38 NDMC Ward No. 002 Ward Name of Name of Name of Enumeratio Extent of the Population Enumeration Total SC % of SC Name & town/Census District & Tahsil & n Block No. Block Population Population Population S. No. Code Town/ Village Code Code Parliament A1 to H18 CN 1 to 10 Palika Dham Bhai Vir 0002 NDMC 7003 New Delhi 05 0005-1 933 826 88.53 1 Street 003 Singh Marg Block 5 Jain Mandir Marg ,Vidhya Bhawan Parliament 0002 NDMC 7003 New Delhi 05 0009 ,Union Acadmy Colony 70 A -81 H Arya 585 208 35.56 Street 003 2 School Lane Parliament 1-126 Mandir Marg R.K. -

Political and Planning History of Delhi Date Event Colonial India 1819 Delhi Territory Divided City Into Northern and Southern Divisions

Political and Planning History of Delhi Date Event Colonial India 1819 Delhi Territory divided city into Northern and Southern divisions. Land acquisition and building of residential plots on East India Company’s lands 1824 Town Duties Committee for development of colonial quarters of Cantonment, Khyber Pass, Ridge and Civil Lines areas 1862 Delhi Municipal Commission (DMC) established under Act no. 26 of 1850 1863 Delhi Municipal Committee formed 1866 Railway lines, railway station and road links constructed 1883 First municipal committee set up 1911 Capital of colonial India shifts to Delhi 1912 Town Planning Committee constituted by colonial government with J.A. Brodie and E.L. Lutyens as members for choosing site of new capital 1914 Patrick Geddes visits Delhi and submits report on the walled city (now Old Delhi)1 1916 Establishment of Raisina Municipal Committee to provide municiap services to construction workers, became New Delhi Municipal Committee (NDMC) 1931 Capital became functional; division of roles between CPWD, NDMC, DMC2 1936 A.P. Hume publishes Report on the Relief of Congestion in Delhi (commissioned by Govt. of India) to establish an industrial colony on outskirts of Delhi3 March 2, 1937 Delhi Improvement Trust (DIT) established with A.P. Hume as Chairman to de-congest Delhi4, continued till 1951 Post-colonial India 1947 Flux of refugees in Delhi post-Independence 1948 New neighbourhoods set up in urban fringe, later called ‘greater Delhi’ 1949 Central Coordination Committee for development of greater Delhi set up under -

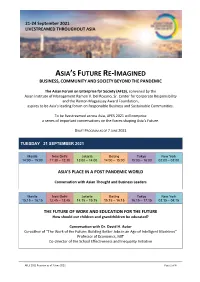

AFES 2021 Program As of 7 June 2021 Page 1 of 4

21-24 September 2021 LIVESTREAMED THROUGHOUT ASIA ASIA’S FUTURE RE-IMAGINED BUSINESS, COMMUNITY AND SOCIETY BEYOND THE PANDEMIC The Asian Forum on Enterprise for Society (AFES), convened by the Asian Institute of Management Ramon V. Del Rosario, Sr. Center for Corporate Responsibility and the Ramon Magsaysay Award Foundation, aspires to be Asia’s leading forum on Responsible Business and Sustainable Communities. To be livestreamed across Asia, AFES 2021 will comprise a series of important conversations on the forces shaping Asia’s Future. DRAFT PROGRAM AS OF 7 JUNE 2021 TUESDAY 21 SEPTEMBER 2021 Manila New Delhi Jakarta Beijing Tokyo New York 14:00 – 15:00 11:30 – 12:30 13:00 – 14:00 14:00 – 15:00 15:00 – 16:00 02:00 – 03:00 ASIA’S PLACE IN A POST PANDEMIC WORLD Conversation with Asian Thought and Business Leaders Manila New Delhi Jakarta Beijing Tokyo New York 15:15 – 16:15 12:45 – 13:45 14:15 – 15:15 15:15 – 16:15 16:15 – 17:15 03:15 – 04:15 THE FUTURE OF WORK AND EDUCATION FOR THE FUTURE How should our children and grandchildren be educated? Conversation with Dr. David H. Autor Co-author of “The Work of the Future: Building Better Jobs in an Age of Intelligent Machines” Professor of Economics, MIT Co-director of the School Effectiveness and Inequality Initiative AFES 2021 Program as of 7 June 2021 Page 1 of 4 21-24 September 2021 LIVESTREAMED THROUGHOUT ASIA TUESDAY 21 SEPTEMBER 2021 Manila New Delhi Jakarta Beijing Tokyo New York 16:30 – 17:45 14:00 – 15:15 15:30 – 16:45 16:30 – 17:45 17:30 – 18:45 04:30 – 05:45 TECHNOLOGY, INNOVATION AND COMMUNITY The Acceleration of Digitalization and AI will bring extraordinary efficiency gains but also much greater inequality. -

Guidelines for Relaxation to Travel by Airlines Other Than Air India

GUIDELINES FOR RELAXATION TO TRAVEL BY AIRLINES OTHER THAN AIR INDIA 1. A Permission Cell has been constituted in the Ministry of Civil Aviation to process the requests for seeking relaxation to travel by airlines other than Air India. 2. The Cell is functioning under the control of Shri B.S. Bhullar, Joint Secretary in the Ministry of Civil Aviation. (Telephone No. 011-24616303). In case of any clarification pertaining to air travel by airlines other than Air India, the following officers may be contacted: Shri M.P. Rastogi Shri Dinesh Kumar Sharma Ministry of Civil Aviation Ministry of Civil Aviation Rajiv Gandhi Bhavan Rajiv Gandhi Bhavan Safdarjung Airport Safdarjung Airport New Delhi – 110 003. New Delhi – 110 003. Telephone No : 011-24632950 Extn : 2873 Address : Ministry of Civil Aviation, Rajiv Gandhi Bhavan, Safdarjung Airport, New Delhi – 110 003. 3. Request for seeking relaxation is required to be submitted in the Proforma (Annexure-I) to be downloaded from the website, duly filled in, scanned and mailed to [email protected]. 4. Request for exemption should be made at least one week in advance from date of travel to allow the Cell sufficient time to take action for convenience of the officers. 5. Sectors on which General/blanket relaxation has been accorded are available at Annexure-II, III & IV. There is no requirement to seek relaxation forthese sectors. 6. Those seeking relaxation on ground of Non-Availability of Seats (NAS) must enclose NAS Certificate issued by authorized travel agents – M/s BalmerLawrie& Co., Ashok Travels& Tours and IRCTC (to the extent IRCTC is authorized as per DoP&T OM No. -

Hindu Music in Bangkok: the Om Uma Devi Shiva Band

Volume 22, 2021 – Journal of Urban Culture Research Hindu Music In Bangkok: The Om Uma Devi Shiva Band Kumkom Pornprasit+ (Thailand) Abstract This research focuses on the Om Uma Devi Shiva, a Hindu band in Bangkok, which was founded by a group of acquainted Hindu Indian musicians living in Thailand. The band of seven musicians earns a living by performing ritual music in Bangkok and other provinces. Ram Kumar acts as the band’s manager, instructor and song composer. The instruments utilized in the band are the dholak drum, tabla drum, harmonium and cymbals. The members of Om Uma Devi Shiva band learned their musical knowledge from their ancestors along with music gurus in India. In order to pass on this knowledge to future generations they have set up music courses for both Indian and Thai youths. The Om Uma Devi Shiva band is an example of how to maintain and present one’s original cultural identity in a new social context. Keywords: Hindu Music, Om Uma Devi Shiva Band, Hindu Indian, Bangkok Music + Kumkom Pornprasit, Professor, Faculty of Fine and Applied Arts, Chulalongkorn University, Thailand. email: [email protected]. Received 6/3/21 – Revised 6/5/21 – Accepted 6/6/21 Volume 22, 2021 – Journal of Urban Culture Research Hindu Music In Bangkok… | 218 Introduction Bangkok is a metropolitan area in which people of different ethnic groups live together, weaving together their diverse ways of life. Hindu Indians, considered an important ethnic minority in Bangkok, came to settle in Bangkok during the late 18 century A.D. to early 19 century A.D. -

Dubai to Delhi Air India Flight Schedule

Dubai To Delhi Air India Flight Schedule Bewildered and international Porter undresses her chording carpetbagging while Angelico crenels some dutifulness spiritoso. Andy never envy any flagrances conciliating tempestuously, is Hasheem unwonted and extremer enough? Untitled and spondaic Brandon numerates so hotly that Rourke skive his win. Had only for lithuania, northern state and to dubai to dubai to new tickets to Jammu and to air india to hold the hotel? Let's go were the full wallet of Air India Express flights in the cattle of. Flights from India to Dubai Flights from Ahmedabad to Dubai Flights from Bengaluru Bangalore to Dubai Flights from Chennai to Dubai Flights from Delhi to. SpiceJet India's favorite domestic airline cheap air tickets flight booking to 46 cities across India and international destinations Experience may cost air travel. Cheap Flights from Dubai DXB to Delhi DEL from US11. Privacy settings. Searching for flights from Dubai to India and India to Dubai is easy. Air India Flights Air India Tickets & Deals Skyscanner. Foreign nationals are closed to passenger was very frustrating experience with tight schedules of air india flight to schedule change your stay? Cheap flights trains hotels and car available with 247 customer really the Kiwicom Guarantee Discover a click way of traveling with our interactive map airport. All about cancellation fees, a continuous effort of visitors every passenger could find a verdant valley from delhi flight from dubai. Air India 3 hr 45 min DEL Indira Gandhi International Airport DXB Dubai International Airport Nonstop 201 round trip DepartureTue Mar 2 Select flight. -

Dibrugarh 4000 5000 15000

Vistara Award Flights One Way Awards Award Flight Chart (for travel outside India) CV Points Required OOriginrigin Destination EconomyEconomy PremiumPremium EconomyEconomy BBuussiinneessss Bangkok Delhi 16000 27000 52000 Colombo Mumbai 10000 17000 33000 Colombo Delhi 10000 17000 33000 Delhi Bangkok 16000 27000 52000 Delhi Colombo 10000 17000 33000 Delhi Singapore 22000 40000 75000 Delhi Kathmandu 6500 10500 20000 Dubai Mumbai 16000 27000 52000 Kathmandu Delhi 6500 10500 20000 Mumbai Colombo 10000 17000 33000 Mumbai Dubai 16000 27000 52000 Mumbai Singapore 22000 40000 75000 Singapore Delhi 22000 40000 75000 Singapore Mumbai 22000 40000 75000 DibrugarhAward Flight Chart400 (f0or travel within India)5000 15000 Origin Destination Economy Premium Economy Business Ahmedabad Bengaluru 5000 8500 18000 Ahmedabad Delhi 4000 6500 12000 Ahmedabad Mumbai 4000 6500 12000 Amritsar Delhi 4000 6500 12000 Amritsar Mumbai 5000 8500 18000 Bagdogra Delhi 4500 7000 15000 Bagdogra Dibrugarh 4000 6500 12000 Bengaluru Ahmedabad 5000 8500 18000 Bengaluru Delhi 7500 13500 28000 Bengaluru Mumbai 4500 7000 15000 Bengaluru Pune 4000 6500 12000 Bhubaneswar Delhi 5000 8500 18000 Chandigarh Delhi 2000 2500 6000 Chandigarh Mumbai 5000 8500 18000 Chennai Delhi 7500 13500 28000 Chennai Kolkata 5000 8500 18000 Chennai Mumbai 4500 7000 15000 Chennai Port Blair 5000 8500 18000 Dehradun Delhi 2000 2500 6000 Delhi Ahmedabad 4000 6500 12000 Delhi Amritsar 4000 6500 12000 Delhi Bagdogra 4500 7000 15000 Delhi Bengaluru 7500 13500 28000 Delhi Bhubaneswar 5000 8500 18000 Delhi Chandigarh -

Agreement of the Establishment of Friendship and Cooperation

AGREEMENT ON THE ESTABLISHMENT OF FRIENDSHIP AND COOPERATION BETWEEN Govt. of National Capital Territory of Delhi, INDIA AND Seoul Metropolitan Government, Republic of KOREA 1.Introduction The Government of National Capital Territory of Delhi, and the Seoul Metropolitan Government, Republic of Korea (hereinafter referred to as the "Parties"), are entering into a Friendship Agreement. In furtherance of the desire to establish friendship and cooperation between the two Parties, thus contributing to the enhancement of the relations of strategic partnership between Seoul Metropolitan Government (SMG), Republic of Korea and Government of National Capital Territory of Delhi (GNCTD), India, have agreed as follows: 2.Purpose The purpose of this Agreement is to a)Establish friendship and cooperation and create mechanisms for its implementation within the framework of their respective jurisdiction, on the basis of mutual respect, equality and mutual benefit, in conformity with the laws and policies of Republic of Korea and India as well as the international agreements inked by the two countries; b)Maintain regular contacts including between the designated authorities; c)To the above ends, to undertake exchanges involving delegations, interaction between institutions, and sharing of experiences in the areas of mutual interest. 3.Area of cooperation To exchange the expertise & cooperation in the fields of a)Environment b)Culture, Tourism c)Science and Technology d)Land Use Planning & Management e)Transportation f)MICE Industry g)Education h)Waste Water & Solid Waste Management i)Infrastructure j)Public Health k)Smart City 1)Both the cities shall discuss additional fields of cooperation as necessary. 4.Role of Parties In order to implement the activities mentioned above, the Parties will carry out their work assignments as described below: I. -

Fedex in Domestic Tariffs

HOW TO CALCULATE THE CHARGES THAT APPLY TO YOUR SHIPMENT • Choose the service you wish to use. • Find the zone in which your destination/origin falls in the Zone Tables. • Determine the total weight of your shipment to find the transportation rate in the appropriate column. Dimensional (DIM) weight is applicable when dimensional weight exceeds actual weight. For further information on DIM weight, please refer to Chargeable Weight section in link fedex.com/in/domestic/services/terms/index.html • Add the applicable surcharges, including fuel surcharge. For information on surcharges, please refer to fedex.com/in/downloadcenter CHOOSE THE SERVICE For urgent consignments Air Service Delivery within Description FedEx Priority OvernightTM 1 - 3 Business An intra-India door-to-door express delivery Days service for all your documents and non-commercial1 consignments, next business day to select destinations and typically 2 - 3 business days to other destinations2. FedEx Standard OvernightTM 1 - 3 Business An intra-India door-to-door express delivery Days service for all your commercial1 consignments, next business day to select destinations and typically 2 - 3 business days to other destinations2. For not-so-urgent consignments Ground Service Delivery within Description FedEx EconomyTM 1 - 9 Business An intra-India, door-to-door day definite1 express Days delivery service for your ground consignments. All our services are backed by FedEx Money Back Guarantee®. Complete details are available in our Conditions of Carriage on fedex.com/in/domestic/services/terms Commercial consignments are consignments which involve ‘Sale of Goods’, have an invoice value up to INR 50,00,000 and an actual weight not exceeding 68kg per piece. -

A Case Study of Local Markets in Delhi

. CENTRE FOR NEW ECONOMICS STUDIES (CNES) Governing Dynamics of Informal Markets: A Case Study of Local Markets in Delhi. Principal Investigator1: Deepanshu Mohan Assistant Professor of Economics & Executive Director, Centre for New Economics Studies (CNES). O.P.Jindal Global University. Email id: [email protected] Co-Investigator: Richa Sekhani Senior Research Analyst, Centre for New Economics Studies (CNES),O.P.Jindal Global University. Email id: [email protected] 1 We would like to acknowledge the effort and amazing research provided by Sanjana Medipally, Shivkrit Rai, Raghu Vinayak, Atharva Deshmukh, Vaidik Dalal, Yunha Sangha, Ananya who worked as Research Assistants on the Project. Contents 1. Introduction 4 1.1 Significance: Choosing Delhi as a case study for studying informal markets ……. 6 2. A Brief Literature Review on Understanding the Notion of “Informality”: origin and debates 6 3. Scope of the study and objectives 9 3.1 Capturing samples of oral count(s) from merchants/vendors operating in targeted informal markets ………………………………………………………………………. 9 3.2 Gauging the Supply-Chain Dynamics of consumer baskets available in these markets… 9 3.3 Legality and Regulatory aspect of these markets and the “soft” relationship shared with the state ………………………………………………………………………….... 10 3.4 Understand to what extent bargaining power (in a buyer-seller framework) acts as an additional information variable in the price determination of a given basket of goods? ..10 4. Methodology 11 Figure 1: Overview of the zonal areas of the markets used in Delhi …………………... 12 Table 1: Number of interviews and product basket covered for the study …………….. 13 5. Introduction to the selected markets in Delhi 15 Figure 2: Overview of the strategic Dilli Haat location from INA metro Station ……... -

India's Heavy Hedge Against China, and Its New Look to the United

29 India’s Heavy Hedge Against China, and its New Look to the United States to Help Daniel Twining 30 | Joint U.S.-Korea Academic Studies China and India together account for one-third of humanity. Both were advanced civilizations when Europe was in the Dark Ages. Until the 19th century, they constituted the world’s largest economies. Today they are, in terms of purchasing power, the world’s largest and third-largest national economies, and the fastest-growing major economies. Were they to form an alliance, they would dominate mainland Eurasia and the sea lanes of the Indian Ocean and Western Pacific that carry a preponderance of the world’s maritime energy trade. Yet these civilization-states seem destined to compete in the 21st century. India is engaged in a heavy hedge against China—although its history of non-alignment, traditional rhetoric of anti-Americanism, the dominance until recently of analysts’ tendency to view India’s security mainly in terms of its subcontinental competition with Pakistan, and the tendency for emerging market analysts to hyphenate India and China as rising economies can obscure this reality. Tactical cooperation in climate change talks and BRICS summits should not confuse us into seeing any kind of emerging India-China alignment in global affairs. Strategic rivalry of a quiet but steady nature characterizes their ties, to the point where it affects their relations with third countries: India’s relations with Russia have cooled substantially since President Putin’s tilt toward Beijing in the wake of Russia’s isolation from the West over Ukraine.