Proquest Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Taken at the Flood: Hercule Poirot Investigates

Agatha Christie Taken at the Flood A Hercule Poirot Mystery Epigraph There is a tide in the affairs of men, Which, taken at the flood, leads on to fortune; Omitted, all the voyage of their life Is bound in shallows and in miseries. On such a full sea are we now afloat, And we must take the current when it serves, Or lose our ventures. Contents Cover Title Page Epigraph Prologue Book I Chapter One Chapter Two Chapter Three Chapter Four Chapter Five Chapter Six Chapter Seven Chapter Eight Chapter Nine Chapter Ten Chapter Eleven Chapter Twelve Chapter Thirteen Chapter Fourteen Chapter Fifteen Chapter Sixteen Chapter Seventeen Book II Chapter One Chapter Two Chapter Three Chapter Four Chapter Five Chapter Six Chapter Seven Chapter Eight Chapter Nine Chapter Ten Chapter Eleven Chapter Twelve Chapter Thirteen Chapter Fourteen Chapter Fifteen Chapter Sixteen Chapter Seventeen About the Author Other Books by Agatha Christie Credits Copyright About the Publisher Prologue I In every club there is a club bore. The Coronation Club was no exception, and the fact that an air raid was in progress made no difference to normal procedure. Major Porter, late Indian Army, rustled his newspaper and cleared his throat. Every one avoided his eye, but it was no use. “I see they’ve got the announcement of Gordon Cloade’s death in the Times,” he said. “Discreetly put, of course. On Oct. 5th, result of enemy action. No address given. As a matter of fact it was just round the corner from my little place. One of those big houses on top of Campden Hill. -

The AGA Song Book up to Date

3rd Edition Songs, Poems, Stories and More! Edited by Bob Felice Published by The American Go Association P.O. Box 397, Old Chelsea Station New York, N.Y., 10113-0397 Copyright 1998, 2002, 2006 in the U.S.A. by the American Go Association, except where noted. Cover illustration by Jim Rodgers. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without prior written permission of the copyright holder, except for brief quotations used as part of a critical review. Introductions Introduction to the 1st Edition When I attended my first Go Congress three years ago I was astounded by the sheer number of silly Go songs everyone knew. At the next Congress, I wondered if all these musical treasures had ever been printed. Some research revealed that the late Bob High had put together three collections of Go songs, but the last of these appeared in 1990. Very few people had these song books, and some, like me, weren’t even aware that they existed. While new songs had been printed in the American Go Journal, there was clearly a need for a new collection of Go songs. Last year I decided to do whatever I could to bring the AGA Song Book up to date. I wanted to collect as many of the old songs as I could find, as well as the new songs that had been written since Bob High’s last song book. You are holding in your hands the book I was looking for two years ago. -

Imazine 2013

IIMAZINEMAZINE 20132013 VOLVOL.. 33 New Castle County Libraries’ Annual Teen Magazine Cover: Frame of Mind by Taylor B. (age 17) 2 TableTable ofof ContentsContents (cover) Frame of Mind Taylor B. 5 A Grimm Fairy Tale Chloe M. 6 Lotus in the Night Sky Sangeeta 7 Alexander and the Star Chloe M. 10 If Life Was One of Us Medha R. 12 Colossal Transformations Kayla V. 13 Spirited Jordyn V. 14 Beyond the Looking Glass Taylor B. 16 Bonnie and Frank Matthew W. 18 Complementary Color Chloe M. 19 Fall Leaves Sangeeta 20 Sleeping Beauty Taylor B. 22 Game of the Season Benjamin 24 Rise of Gold Caroline 25 Beauty of Fall Sangeeta 26 The Suspicious Friends Donovan T. 28 Time Arianna H. 29 Sundial Taylor B. 30 To the Voices Inside My Head Medha R. 31 Mistakes Matter Jordyn V. 33 Winding Path in Shadow and Light Taylor B. 34 Damsel Taylor B. 36 Give Me Arianna H. 37 Smile Medha R. 38 Vibrant Jordyn V. 39 Now this is emptiness… Taylor B. 40 Room 401 Rebekah M. 42 Wounded Soldier Caroline 45 The Hum Chloe M. 47 Day's End Jordyn V. 3 4 A Grimm Fairy Tale by Chloe M. (age 16) Like looking through a looking glass, that's not completely clear a beautiful and dark glimpse of neither here nor there a world of dim light and foreignness of deep shadows and night a place where demons kiss and angels learn to bite you see it in old stories that warn of curiosity where innocent and desperate unleash the caged ferocity those frightening tales of caution of a place that we all know that from the time we're children we fear but want to go 5 Lotus in the Night Sky by Sangeeta C. -

A Don West Reader West End Press

Lincoln Memorial University LMU Digital Commons Copyright-Free Books Collection Special Collections 1985 In a Land of Plenty: A Don West Reader West End Press Don West Constance Adams West Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lmunet.edu/csbc Part of the Appalachian Studies Commons, and the Poetry Commons Recommended Citation End Press, West; West, Don; and West, Constance Adams, "In a Land of Plenty: A Don West Reader" (1985). Copyright-Free Books Collection. 1. https://digitalcommons.lmunet.edu/csbc/1 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Special Collections at LMU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Copyright-Free Books Collection by an authorized administrator of LMU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. With sketches Constance Adams West No Grants This book is not supported any grant, governmental, corporate or PS 3545 .E8279 16 1985 private. It is paid for, directly or indirectly, by the people who support and In a land of plenty have Don West's vision, and it both reflects and proves their best - The publisher No Purposely this book is not copyrighted. Poetry and other creative efforts should be levers, weapons to be used in the people's struggle for understanding, human rights, and decency. "Art for Art's Sake" is a misnomer. The poet can never be neutral. In a hungry world the struggle between oppressor and oppressed is unending. There is the inevitable question: "Which side are you on?" To be content with as they are, to be "neutral," is to take sides with the oppressor who also wants to keep the status quo. -

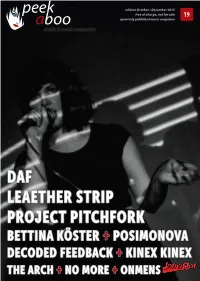

Daf Leaether Strip Project Pitchfork

edition October - December 2015 free of charge, not for sale 19 quarterly published music magazine DAF LEAETHER STRIP PROJECT PITCHFORK BETTINA KÖSTER + POSIMONOVA DECODED FEEDBACK + KINEX KINEX THE ARCH + NO MORE + ONMENS - 1 - WOOL-E TOP 10 WOOL-E TAPES Wool-E Tapes is a spin-off of Wool-E Best Selling Releases Shop to release everything its owner (July/Aug/Sept 2015) likes, on tape INTERNATIONAL CASSETTE 1. SHE PAST AWAY STORE DAY (October 17th) Narin Yalnizlik (LP/CD) For the 3d instalment of International Cassette Store Day we will be 2. PURE GROUND releasing 4 tapes (see below). Sound Standard Of Living (LP/CD) & Vision and Charnier will promote 3. VOLKOVA their tape by means of a short gig Sangre (CD) in the shop. Check the website or 4. QUAL facebook for the exact timing. Sable (LP/CD) Upcoming: 5. DADA POGROM WET020 Unidentified Man - Dissociative Identity C50 Kolophonium (CD) WET021 Klankdal - Nachtkarkassen C85 6. VARIOUS WET022 Sound & Vision – Golden Years C26 Another Cold World (LP/CD) WET023 BARST (released on 1st 7. KVB November) Mirror Being (LP/CD) WET024 Charnier C25 8. MONNIK / ONRUST Still hot: Split Tape (MC) WET016 - MAYZ – The Void C67 WET017 - Howling Larsons - Midnight 9. L’AVENIR Folk C49 Etoiles (LP) WET018 - Kinex Kinex - Polytheistic 10. BLEIB MODERN Christmas C31 All Is Fair In Love And War(LP/CD) http://wool-e-tapes.bandcamp.com The Wool-E Shop - Emiel Lossystraat 17 - 9040 Ghent - Belgium VAT BE 0642.425.654 - [email protected] - 32(0)476.81.87.64 www.peek-a-boo-magazine.be - 2 - contents 04 CD reviews -

CATALOGX 87.Pdf

E R T A N M E N T BIG NEWS, fRANIINSTBN, TIIE RDT•m VEIIIII (1831) BLACDAWK MOVESI \ Big news and good news for our many customers nationwide! Blackhawk Films, for years based in Davenport, Iowa is heading west to Hollywood. Effective September 18, 1987, Blackhawk Films moved its operations closer to the heart of the industry. The new facilities mean faster response and even more personal attention given to filling your orders. The most outstanding new feature that goes with the move is the extension of phone service to 24 hours a day, every day of the year. At Blackhawk Films, we keep trying to find new ways to retain our customers and give you the kind of service you deserve ... the best. You can see that effort most clearly in this catalog's selection of collectable entertainment. Just looking through our exclusive LANDMARKS IN ENTERTAINMENT Section gives you a taste of the kinds of special videocassettes we have to offer. Not just entertaining features, Blackhawk strives to select high-quality, important work that is valuable entertainment. Titles like the original FRANKENSTEIN, TOP HAT, DIRECTOR: James Whales PRODUCER: Carl Laemmle Jr. MAKE-UP: Jack Pierce CAST: Boris Ka.rfoff. Colin MR. SMITH GOES TO WASHINGTON, Clive, Mae Clarke, Edward Van Sloan, John Boles, Marilyn Harris and Dwight Frye SONS OF THE DESERT and the rest read like a roll call of the greatest films from For the first time in 50 years, this classic adaptation of Mary Shelly's novel can be seen the way its Hollywood's heyday. -

Comedy, 109-12, 1200 Ft

FALL 1985 VOL. 390 © 1985 Blackhawk Films, One Old Eagle Brewery, Davenport, Iowa 52802 Prices subiect to change BLACKHAWK'S NEWSREEL • As we heod into the foll seoson with its glorious doys of color, football games, crisp oir and great get togethers, we want to remind you that our mail order plont will be closed the day after Thanksgiving, but we' ll be here again on the very next Monday to handle your Christmas wants and needs. We are making this reminder early so you will know about it, AND to RE MIND YOU to begin to get your Christmas Orders in Early so that we can have time to get all of them to you. Any orders TOTALING $50 or more, re ceived here in Davenport BY NOVEMBER 10, 1985 will qualify for our Early Order Christmas Discount of $5.00 off the order! Beginning with this catalog we are very happy to begin adding the complete line of motion pictures from Republic Pictures Corpora tion. As the months go by we will be odding more titles from their great lib rary of film titles. Republic is one of the oldest studios in the movie business ond the one at which many of the Gene Autry films were produced. You'll love the many great offerings we can now make available to you. As a Special Introductory Offer to this new and exciting catalog you may order ANY Blackhawk or Repulbic movie at the regular price shown and DEDUCT 20% on those titles. This introductory offer will end December 31 , 1985. -

Tales of a Fourth Grade Nothing.Pdf

My biggest problem is my brother, Farley Drexel Hatcher. Everybody calls him Fudge. I feel sorry for him if he’s going to grow up with a name like Fudge, but I don’t say a word. It’s none of my business. Fudge is always in my way. He messes up everything he sees. And when he gets mad he throws himself flat on the floor and he screams. And he kicks. And he bangs his fists. The only time I really like him is when he’s sleeping. He sucks four fingers on his left hand and makes a slurping noise. When Fudge saw Dribble he said, “Ohhhhh . see!” And I said, “That’s my turtle, get it? Mine! You don’t touch him.” Fudge said, “No touch.” Then he laughed like crazy. BOOKS BY JUDY BLUME The Pain and the Great One Soupy Saturdays with the Pain and the Great One Cool Zone with the Pain and the Great One Going, Going, Gone! with the Pain and the Great One Friend or Fiend? with the Pain and the Great One The One in the Middle Is the Green Kangaroo Freckle Juice THE FUDGE BOOKS Tales of a Fourth Grade Nothing Otherwise Known as Sheila the Great Superfudge Fudge-a-Mania Double Fudge Blubber Iggie’s House Starring Sally J. Freedman as Herself Are You There, God? It’s Me, Margaret It’s Not the End of the World Then Again, Maybe I Won’t Deenie Just as Long as We’re Together Here’s to You, Rachel Robinson Tiger Eyes Forever Letters to Judy Places I Never Meant to Be: Original Stories by Censored Writers (edited by Judy Blume) PUFFIN BOOKS Published by the Penguin Group Penguin Young Readers Group, 345 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, U.S.A. -

Steve Discog Long

Artist Title Label Function A-ha The Sun Always Shines On TV Warner Additional Production, Mixing A-ha Train of Thought WEA Int. Remixing Alice Cooper Trash Epic Mixing Alice Cooper Life and Crimes Of Alice Cooper (4 CD set) Rhino Mixing Alphaville Afternoons In Utopia Atlantic Producer Alphaville Singles Collection Atlantic Producer, Mixing Alphaville First Harvest: The Best Of Alphaville 1984-1992 WEA Producer, Remixing Alphaville Alphaville Amiga Producer Anderson/Bruford/Wakeman/Howe Anderson Bruford Wakeman Howe Arista Mixing Anderson/Bruford/Wakeman/Howe Brother Of Mine (#1) Arista Mixing Anderson/Bruford/Wakeman/Howe Brother Of Mine (#2) Atlantic Mixing Anderson/Bruford/Wakeman/Howe Order Of The Universe Arista Mixing Anderson/Bruford/Wakeman/Howe Quartet (I'm Alive) Atlantic Mixing Animotion I Engineer Mercury Mixing Anthrax Persistence Of Time Megaforce/Island Mixing Anthrax Attack of the Killer B's (Clean) Island Mixing Anthrax Attack of the Killer B's Island Mixing Anthrax Anthrax Live: The Island Years Island Producer, Mixing Anthrax N.F.V.:Oidivnikufesin (Clean) Polygram Engineer Anthrax Return Of The Killer A's: The Best Of Anthrax Beyond Mixing Anthrax Universal Masters Collection Island Mixing Anthrax Anthrology: No Hit Wonders 1985-1991 Island Mixing Anthrax Got The Time (Picture disc) Island/Megaforce Mixing APB Something to Believe In Link Producer Apollonia The Same Dream Warner Remixing Aretha Franklin Who's Zooming Who Arista Additional Production, Mixing Aretha Franklin Aint Nobody Ever Loved You Arista Remixing -

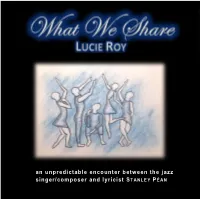

An Unpredictable Encounter Between the Jazz Singer/Composer and Lyricist STANLEY PÉAN

an unpredictable encounter between the jazz singer/composer and lyricist S TANLEY P ÉAN J’ai fait la connaissance de Lucie Roy complètement par hasard, un de ces hasards heureux et fructueux que la vie nous réserve en toute petite quantité. À la fin de l’été 2017, elle effectuait son retour sur la scène du jazz après une absence de quelques années, dans le cadre d’un concert-bénéfice au profit de la Fondation canadienne du cancer du sein qu’on m’avait demandé de promouvoir dans le cadre de mon émission de jazz à la radio d’ICI Musique. J’avais volontiers accepté, impressionné par le courage de cette autrice-compositrice-interprète qui avait refusé de se laisser abattre par l’adversité. Si impressionné à vrai dire que je lui avais dès lors offert un premier texte de chanson, inspiré par la perception que j’avais d’elle, « I Don’t Want To Go ». Quelques temps après, elle m’impressionnait à nouveau avec la maquette de ce qui allait devenir la première d’une série de chansons nées de notre travail conjoint au fil des mois suivants. Rarement ai-je connu dans ma vie de créateur une collabora- tion aussi intense et assidue, aussi stimulante. Encore et encore, Lucie a continué de m’impressionner, en se colletant aux thèmes pas toujours faciles, pas toujours joyeux, jamais évidents des textes que je lui proposais. Vous comprendrez alors notre fierté commune de vous offrir maintenant de découvrir sur What We Share ce que nous avons concocté dans une totale complicité. -

Kein Weg Zurück in Syrien Warten Gefangene Islamisten Auf Einen Prozess

Strassenmagazin Nr. 472 davon gehen CHF 3.– Bitte kaufen Sie nur bei Verkaufenden 27. März bis 16. April 2020 CHF 6.– an die Verkaufenden mit offiziellem Verkaufspass Corona- Krise Wir brauchen Sie! Daesch Kein Weg zurück In Syrien warten gefangene Islamisten auf einen Prozess. Keiner will ihn führen. Seite 8 Surprise 472/20 3 INFOS ZUM VERKAUFSSTOPP Der Verein Surprise stellt den Verkauf des Strassenmagazins und die Sozialen Stadtrundgänge bis auf Weiteres ein. So soll die besonders vulnerable Gruppe der Armutsbetroffenen geschützt und ein Beitrag zur Eindämmung des Coronavirus geleistet werden. Die Massnahmen gelten bis auf Weiteres. Das aktuelle Surprise Strassenmagazin steht in dieser Zeit kostenlos via Website zum Download bereit und wird in kleiner Auflage weiterhin für AbonnentInnen gedruckt. Der Verein setzt alles daran, die Verkaufenden und Stadtführenden finanziell zu unterstützen und weiterzubegleiten. Wir sind aber dringend auf Ihre Hilfe angewiesen. Die Massnahmen stellen die Verkaufenden und Stadtführenden sowie den Verein Surprise vor massive Herausforderungen. Viele der rund 450 Verkaufenden und 14 Stadtführenden sind armutsbetroffen und für ihr Überleben vom Verkauf des Strassenmagazins und von den Führungen abhängig. Der Verein Surprise wird nicht staatlich subventioniert und ist zu 65 Prozent vom Heftverkauf abhängig. Surprise ist deshalb auf Ihre Solidarität angewiesen. Unterstützen Sie uns mit einer Spende für die betroffenen Verkaufenden und Stadtführenden sowie für den Verein Surprise. Vielen herzlichen Dank für -

Mark Hollis, Leader of ’80S Band Talk Talk, Is Dead

LOG IN Mark Hollis, Leader of ’80s Band Talk Talk, Is Dead Mark Hollis of Talk Talk in 1986. The success of the group’s second album, “It’s My Life,” gave Mr. Hollis and the rest of the band free rein to experiment. Rob Verhorst/Redferns, via Getty Images By Daniel E. Slotnik Feb. 27, 2019 Mark Hollis, the frontman for the British band Talk Talk, which had synth-pop hits in the early 1980s before veering into a more experimental sound that influenced a generation of musicians, has died. Mr. Hollis, about whom personal details are scarce, was widely reported to have been 64. A Facebook page devoted to the group confirmed the death, citing Keith Aspden, Mr. Hollis’s former manager, but provided no further details. Talk Talk was formed in London in 1981, when new wave and synth-pop groups like A Flock of Seagulls and Duran Duran were beginning to receive heavy airplay. Talk Talk’s biggest hits, among them “It’s My Life” and “Such a Shame,” were typical of the style: buoyant songs built on catchy, danceable beats and Mr. Hollis’s plaintive lyrics. The band at first consisted of Mr. Hollis on vocals, guitar and piano, Lee Harris on drums, Paul Webb on bass and Simon Brenner on keyboards. Mr. Brenner left after the group released its first album, “The Party’s Over,” on EMI in 1982, and Tim Friese-Greene became the band’s producer and unofficial fourth member. Talk Talk toured with Duran Duran and broadened its American audience with videos on MTV.